Americans have always been a people on the move. The first settlers at Jamestown and Plymouth had barely established a foothold in the early 1600s when they began to push into the continent’s interior. Adventurous settlers, anxious to improve their fortunes, took up new lands in the west, confidently expecting them to be better than the lands they left behind. Westward movement of the colonists continued throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. By the time they declared their independence from Britain in 1776, Americans had pushed the line of settlement westward to the Appalachian Mountains.

After the Revolution, the westward movement of Americans intensified. During the first two decades of the nineteenth century, Americans moved west in such great numbers that historians refer to that mass movement as the “Great Migration.” In 1800, there were only two states west of the Appalachians — Kentucky and Tennessee. By 1820, there were eight: Kentucky, Tennessee, Ohio, Louisiana, Illinois, Indiana, Mississippi, and Alabama. The population of these eight "western" states had grown from 386,000 persons in 1800 to 2,216,000 in 1820. Mississippi was a product of this Great Migration.

The Mississippi Territory

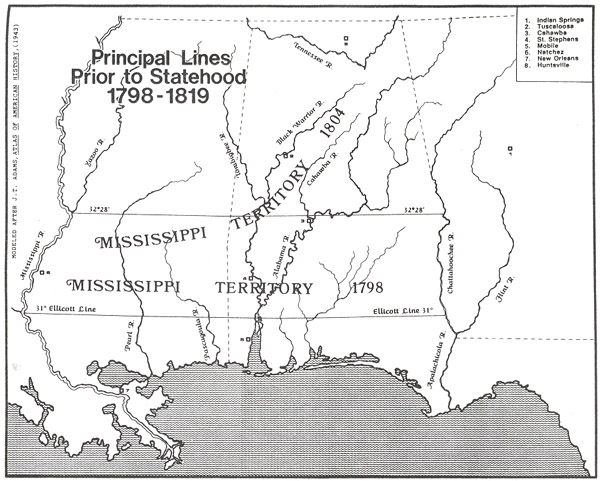

The Mississippi country was opened to settlement in 1798 when Congress organized the Mississippi Territory. (Until it became a separate territory in 1817, Alabama was part of Mississippi.) A few settlers already lived in Mississippi when it became a territory. They were concentrated in two principal areas — the Natchez District and the lower Tombigbee settlements above and west of Mobile. Approximately 4,500 people, including enslaved people, lived at Natchez, considerably more than the combined free and enslaved population of 1,250 that inhabited the Tombigbee settlements in 1800. Outside of these two areas, the territory was populated by the Chickasaw and Choctaw nations who were a majority of residents at that time.

The deprivation and hardship that awaited White immigrants in the raw, primitive Mississippi wilderness of 1800 raises a fundamental question: Why would a person choose to leave the comfort and convenience of an established farm in one of the older communities for the perilous uncertainty of life in the Mississippi wilds? The answer to this question, in a word, is — Opportunity.

For the average White person, economic opportunities had diminished in the older southern agricultural states as the available supply of fertile land dwindled. Generations of ruinous agricultural practices had, by 1800, exhausted the soils of the old plantations. This made the rich virgin land of Mississippi all the more attractive. The decline in soil fertility of the upper South had been accompanied by a sharp decrease in demand for tobacco, the region's staple product.

The Cotton Kingdom

After the Revolution, the decline in European demand for southern staple products, especially tobacco and rice, caused anxiety among southern farmers. In the 1790s, the invention of the cotton gin, together with a sharp rise in the foreign demand for southern cotton, created outstanding economic opportunities for southern farmers and fueled the Great Migration. The rich soils of the Mississippi Territory, its favorable environment for cotton culture, and the high prices being paid in England for cotton, led to the genesis of the Cotton Kingdom, which was based on enslaved labor. Mississippi, with soil and climate ideally suited to cotton culture, became the center of southern cotton production and slavery during the first half of the nineteenth century.

Closely linked to the notion that Mississippi offered exceptional economic opportunities for the immigrant was the widespread belief that the Territory was an idyllic “Garden of Eden,” an unlimited expanse of fertile country “like the land of promise, flowing with milk and honey.”

One Mississippi immigrant described his new home as “a wide empty country with a soil that yields such noble crops that any man is sure to succeed.” Another new settler wrote to family back in Maryland that “the crops [here] are certain . . ., and abundance spreads the table of the poor man and contentment smiles on every countenance.”

Thousands of immigrants moved to the Mississippi Territory believing they were taking up residence in a land of unsurpassed opportunity. Hard work and resourcefulness were sure to be rewarded with prosperity, security, and happiness. Mississippi was a land where opportunities for immigrants to achieve economic independence and wealth seemed boundless. For White Americans, though certainly not for those enslaved, Mississippi symbolized the promise of American life.

Settlers Pour into Territory

During the first phase of the Great Migration, which began in 1798 and continued until 1819, two distinct waves of immigrants swept into the Territory. The first wave began when the Territory was organized and subsided when the War of 1812 began. The second wave developed after the war ended in 1814. It peaked in the years 1818-1819 and receded after the Panic of 1819 brought about a general economic depression. In the period from 1798 to 1812, the flow of immigrants was steady but unspectacular, at least by comparison with the 1815-1819 period. In the first period, settlers moved primarily into three general areas — the Natchez country, the lower Tombigbee River basin, and the Tennessee Valley.

Of these three regions, Natchez received the largest number of settlers during the first period of migration. In 1798, Natchez had a total population, White and Black, of 4,500 persons. Two years later the counties of Adams and Pickering (later renamed Jefferson County), into which Natchez had been divided in 1799, contained a total population of 4,446 White people and 2,995 enslaved persons. By 1811, a tier of five new counties lying north and south of Adams County and eastward to the present Alabama state line had been created. The total population of these counties amounted to 31,306 persons, 14,706 of whom were enslaved.

During the same period, the settlements along the lower Tombigbee, in what became part of Alabama in 1817, grew much more slowly than the Natchez country. The Mississippi portion of the Territory increased by almost 27,000 persons during the period 1798-1810. The settlements in south Alabama grew by less than 3,000.

Migration to the Territory slowed during the War of 1812. But after peace was made in 1815, immigration resumed and surpassed anything that had ever been witnessed. Thousands of immigrants began to pour into the country. By horse, by wagon, by boat, and on foot, the flood of humanity swept into the Territory. One traveler, during nine days of travel in 1816, counted no fewer than 4,000 immigrants coming into the Territory during nine days of travel. Residents of the older states, such as Virginia and the Carolinas, began to fear that the “Mississippi Fever” would depopulate their states. Everyone seemed to be moving to Mississippi.

A State is Born

In 1819 an economic panic, followed by a general depression, arrested the migration. But by that time enough immigrants had settled in the country to allow both Mississippi and Alabama to come into the Union as new states — Mississippi in 1817 and Alabama in 1819. During the 1810-1820 decade, Mississippi’s population more than doubled to 42,176 White people and 33,272 enslaved persons. The total population had grown by more than 44,000 persons during the decade. The Choctaw nation had about 20,000 in the central and southern part of the state. The Chickasaw numbered about 4,000 in north Mississippi.

The Alabama portion of the Territory grew even more during the ten years, increasing sixteen fold. In 1810, 6,422 White people and 2,624 enslaved persons lived in the Alabama section of the Territory. In 1820, the numbers had grown to 99,198 whites and 47,665 slaves, an increase of 137,817 persons.

The Panic of 1819 ended the most important phase of the Great Migration. In the 1820s and 1830s immigration into Mississippi would resume. But Mississippi's future had already been set. The Great Migration had brought into the state an agricultural people seeking good land for growing cotton. In a remarkably short time, they made Mississippi one of the principal cotton-producing states of the Old South, albeit at the cost of slave labor and the eviction of native people. Cotton would make Mississippi one of the wealthiest states of the Union by mid-nineteenth century.

Charles Lowery, Ph.D., is history professor emeritus, Mississippi State University.

Further reading:

Abernethy, Thomas P. The South in the New Nation, 1789-1819, Volume V of A History of the South, Baton Rouge, Louisiana State University Press, 1961.

Billington, Ray Allen and Ridge, Martin Westward Expansion: A History of the American Frontier, New York and London, Macmillan Publishers, 1982.

Bettersworth, John K. The Land and the People, Austin, Texas, Steck-Vaughn Co., 1981.

Skates, John Ray Mississippi: The Study of Our State, Walthall Publishing Co., 1998.

Southerland Jr., Henry D. and Brown, Jerry E. The Federal Road Through Georgia, the Creek Nation, and Alabama, 1806-1836, University of Alabama Press, 1989.