By 1932 the Great Depression had the country in its relentless grip and most Americans believed that something was very wrong.

Children went hungry, adults died of malnutrition, and in the richest agricultural region in the world, the Mississippi River Delta, families survived on the “3-Ms” – meal, meat, and molasses. There were tons of food around, but it was not profitable to transport it, to sell it. American agriculture was booming, yet people were under-fed. Warehouses were full of clothing, yet people were dressed in rags because they could not afford to buy new clothing. The situation was as bleak in the industrial economy as it was in agriculture. Industrial production had fallen by fifty percent.

Sharecroppers suffer

In the 1932 U. S. presidential campaign, New York Governor Franklin D. Roosevelt promised voters he would see to it that Americans got a “New Deal.” Part of the New Deal was a program designed to increase the price of farm products. The Agricultural Adjustment Administration (AAA) program paid farmers to take some land and livestock out of production. While AAA programs helped to rescue large, medium, and even small land-owning farmers, the same program drove poor White and Black sharecroppers, the least powerful Americans, to the brink of starvation.

Over eighty percent of the farms in the Lower Mississippi River Delta Region were worked by sharecroppers and over eighty percent of those sharecroppers were Black. Sharecroppers did not have money, tools, livestock, or land. Sharecroppers agreed to work the landowner’s land for a share of the proceeds from the sale of the crop. They bought their meal, meat, and molasses on credit from the planter’s commissary or from the local “furnishing” store. Few sharecroppers in the delta region had received cash income from their share of the crop since 1920. Most of them ended the year “in the hole.”

The life of a delta sharecropper was hard. In the 1930s, it got harder. Taking advantage of the government AAA payments, planters soon began evicting sharecroppers, especially their least favorite ones. The least favorite of all sharecroppers were the men and women who had joined the Southern Tenant Farmers Union (STFU). The STFU, which started in Arkansas and spread to other states, attempted to organize Black and White tenant farmers into a union in order to get better working conditions and a fair deal in their dealings with the planters.

In late 1935, C. H. Dibble, a planter in Parkin, Arkansas, evicted almost 100 sharecropper families. In March 1936 some of those families made their way to a cooperative farm at Hillhouse, Mississippi, lured by the promise of social equality and economic stability.

Visionary experiment

At a place called Delta Cooperative Farm, former Dibble sharecroppers and other families from Arkansas and Mississippi (nineteen Black families and twelve White families) began a radical and visionary experiment in American agricultural history. The organizers of the Delta Cooperative Farm were William Amberson, a physiology professor at the University of Tennessee Medical School in Memphis, Tennessee, who was also the leader of the Memphis Chapter of the Socialist Party of America; Sherwood Eddy, world traveler, ordained minister, and missionary who was a student of Reinhold Niebuhr, one of America’s most famous intellectuals; Sam Franklin, Eddy’s student; and H. L. Mitchell, executive secretary of the STFU.

Eddy, Niebuhr, Franklin, and Mitchell felt that the answer to the problem of sharecropping was ownership. Amberson, Eddy, and Franklin toured the area around Memphis in search of property on which to establish a cotton plantation that would eventually belong to the workers. William H. Timken of Canton, Ohio, had once given Eddy $20,000 and told him to use the money where it would do the most good. In March 1936, Eddy used this contribution on behalf of the newly formed Board of Trustees of Delta Cooperative Farm to finance the purchase of a 2,138-acre farm in Bolivar County, Mississippi. Eddy’s goal was to use “Christian ethics in the struggle against social injustices.”

Delta Cooperative Farm

Franklin was appointed resident director of the farm. The farm soon buzzed with activity. The newly arrived families signed contracts to become members of the Delta Farm Cooperative. The contract stated they were to share in the profits and produce of the farm in accordance to their labor. Read the contract. The members rushed to provide housing for their families and to prepare for the farm’s first crop.

In their first year, the Delta Cooperative Farm members established a sawmill, built houses for all families, cleared new land, and despite a late start and bad weather, produced 152 bales of cotton. Members also planted and tended a large vegetable garden that supplied them a more balanced diet. They named the cooperative Rochdale after a cooperative begun in 1844 in England.

According to the rules that Franklin established, all decisions about farm operations were entrusted to a council of five elected cooperative members. The rules required that no more than three of the council members be of the same race. Although the farm was supposed to be managed by the council, Franklin had the right to veto or change any decision made by the council. The council, sometimes with Franklin’s strong suggestions, decided what to plant, where to plant, when to plant, and which members were to do what work. The council also oversaw and planned the construction of housing and other farm buildings. The farm started dairy operations, a logging business, raised chickens and hogs, and established their own “furnishing” store.

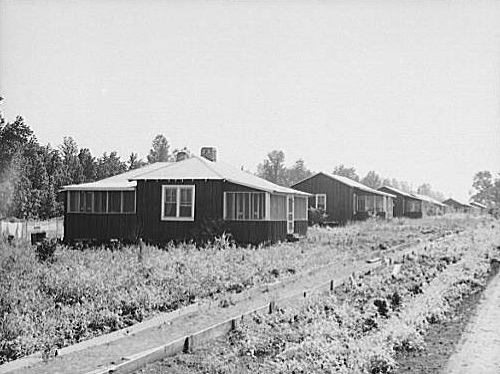

In addition to these purely farm matters, the council was responsible for decisions affecting the entire community, including disciplinary matters with the authority to dismiss members from cooperative membership. It was decided that the families would not segregate themselves by race. White and Black cabins would be separated only by the road that ran through the farm. And, since the state of Mississippi provided only four and one-half months of schooling for Black children while White children went to school for eight months, White members of Delta Cooperative Farm asked the council to establish a school for Black children to make up the difference. Delta Cooperative Farm at Hillhouse, Mississippi, was probably the only place in Mississippi at the time where Black and White children received roughly equal educational opportunities.

Delta Cooperative Farm recruited a nurse, Lindsey Hail, who had earned her R.N. at Massachusetts General Hospital, and Dr. David Minter, a recent graduate of the University of Pennsylvania Medical School, to provide medical care. The members of Delta Cooperative Farm, possibly for the first time in their lives, had a balanced diet, adequate medical care, and the bright hope of financial security. Things were looking good down on Delta Cooperative Farm.

Eddy gave an encouraging report on the farm’s first year of operation in The Christian Century. The members of the cooperative had distributed $8,909 in dividends, an average of $327.53 per family. Each family had also received an average of $122.29 in deferred certificates for the labor involved in cabin construction and clearing fields. In the year in which the average southern tenant farmer earned $212 and the average Delta sharecropper received no cash, the Delta Cooperative Farm families earned, in cash and deferred certificates, $449.82.

Creating a community

The Cooperative Farm’s goals were ambitious. Franklin and his staff put as much time and effort into spiritual, social, and educational goals as they did economic ones. Franklin conducted religious services every Sunday. Sometimes prominent speakers, such as sociologist Arthur Raper and Bishop William Scarlett, spoke at the farm. Lessons in home economics, book reviews, plays written and performed by the children, and movie screenings became a regular part of the operations at Delta Cooperative Farm. Beginning in the summer of 1937, college students, recruited by the Quakers’s American Friends Service Committee, came to perform volunteer work at Delta Cooperative Farm. These volunteers built bridges, cared for children, cleared fields, chopped cotton, cooked, and fell in love.

The nation took notice of Delta Cooperative Farm. New York newspapers and national magazines published articles about the farm. First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt asked that someone from the farm visit her and tell her all about Delta Cooperative Farm.

Trouble among the trustees

Despite the national attention, the favorable comments, and the apparent financial success of Delta Cooperative Farm, all was not going well down on the farm. A bitter division arose among members of the board of trustees. Amberson charged that Franklin and Eddy deliberately misinformed the public in order to raise contributions for the farm. The farm’s balance sheet was healthy, said Amberson, only because of contributions; that farm operations had actually lost money. Amberson believed that working men were capable of managing their own operations if given a chance. He felt that the only way for the working class to advance was for it to develop leadership and management skills. Amberson claimed that Niebuhr, Eddy, and Franklin were Christian socialists who were content to have the masses rely on charity for their living.

Amberson was right, the farm never made a profit on its operations. All the money paid to the members and all the improvements made to the farm were paid for by charitable donations.

In addition, the attitude of racial harmony and equality so praised in national publications seems to have been overstated. Franklin did not allow the news to leave the farm of an “indignation meeting” called by Black members to protest unfair treatment by Franklin. And, the Mississippi neighbors were not as tolerant of the experiment as people were led to believe. The president of Delta State Teachers College in nearby Cleveland, wrote to a friend about potential trouble out there on the farm. They were, he said, “misterin’ those niggers out there.” Furthermore, warned W. M. Kethley, “The attendant loose talk also runs along bad lines: social equality and what have you.”

Providence Cooperative Farm

In 1938, the trustees moved operations to a newly purchased farm near Cruger in Holmes County, about eighty miles south of Delta Cooperative Farm. As cooperative members enlisted in the military and found jobs in the growing wartime industry at the start of World War II, and as the need for farm labor decreased as technology invaded the cotton fields, Delta Cooperative Farm did not replace vacating members.

In 1942, the trustees sold the Delta Cooperative Farm to a levee contractor and concentrated all its efforts on Providence Cooperative Farm. A. Eugene Cox was named resident director of Providence Farm. Cox had joined Delta Cooperative in 1936 as accountant and bookkeeper. He would spend the next twenty years in service to the two cooperatives. Like its predecessor, Providence Farm continued to exist not on farm operation profits but on charity.

In 1955, a teenaged White girl reported that some Black boys at Providence had whistled at her. This happened a week after an all-White male jury had acquitted two White men for the kidnapping and murder of Emmett Till, a black teenager from Chicago visiting relatives in Mississippi, who had reportedly made a pass at a White woman in a rural store. On a September evening in 1955, a large crowd of Holmes County citizens met at Tchula High School to hear the taped “confessions.” The citizens of Tchula, incited by members of the White Citizens Council, decided that Providence Cooperative Farm exerted a bad influence on the community in general and upon African Americans in particular. All the staff and residents of Providence Cooperative Farm were advised to leave the county.

They all did leave and, in 1956, the trustees sold Providence Farm to Delta Foundation, Inc. for the sum of one dollar. The Delta Foundation later donated approximately 289 acres of Providence property to the Mississippi Department of Archives and History. In 1991, the foundation sold the remaining property to the Nature Conservancy.

In retrospect, the foundations for the cooperatives were faulty: by the late 1930s, farms the size of the Delta Cooperative were proving to be unprofitable – to make money growing cotton, one had to farm on a much larger scale; and the internal division between the political socialists led by Amberson and the Christian socialists led by Neibuhr, made it extremely difficult to cooperate in this kind of venture. But perhaps the most important reason for the farm’s failure was the unwillingness of African Americans to remain servile and silent. They were no longer content with a predetermined class, status, and income. The years during and following the closing of Delta and Providence cooperative farms were the years in which African Americans in the Delta, and elsewhere in the South, turned their eyes on the prize of racial equality and opportunity.

Fred C. Smith is a doctoral candidate in history at the University of Southern Mississippi.

Lesson Plan

-

Delta Cooperative Farm, Hillhouse, Mississippi. June 1937 Dorothea Lange photograph courtesy Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Farm Security Administration and Office of War Information Collection. Call No. LC-USF34-017288-C. -

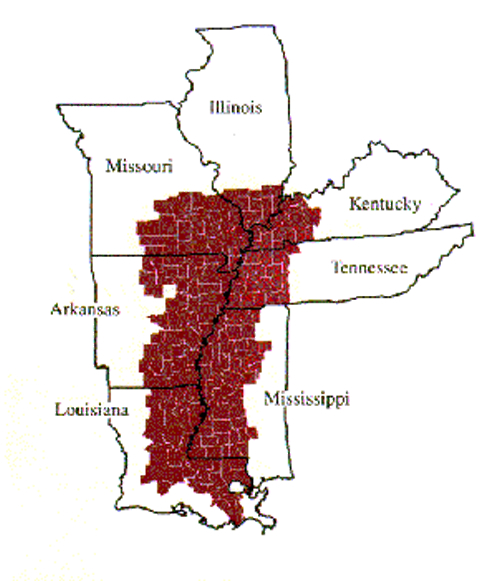

The Lower Mississippi River Delta Region is defined as a 219-county strip along the Mississippi River in Arkansas, Illinois, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, Missouri, and Tennessee. Source: Lower Mississippi Delta Commission.

-

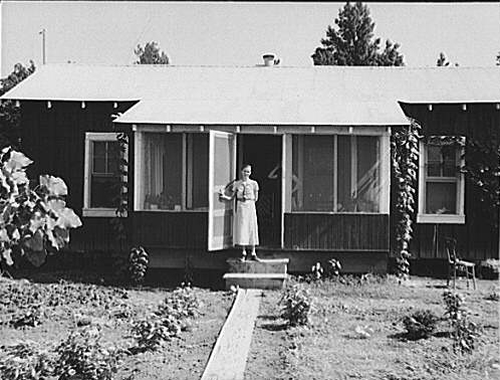

A Delta Cooperative farmstead after a year of operation at Hillhouse, Mississippi. June 1937 Dorothea Lange photograph courtesy Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Farm Security Administration and Office of War Information Collection. Call No. LC-USF34-017336-C. -

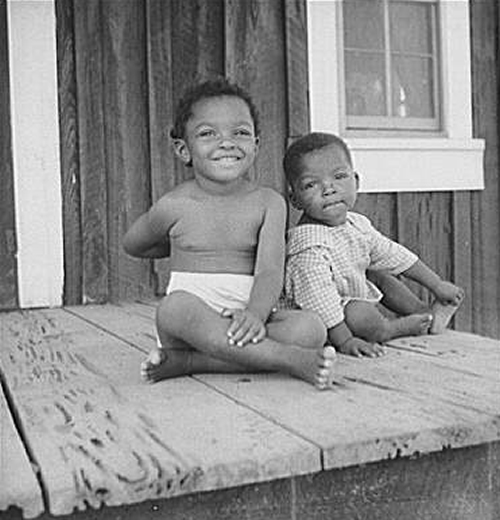

Children of the Delta Cooperative. June 1937 Dorothea Lange photograph courtesy Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Farm Security Administration and Office of War Information Collection. Call No. LC-USF34-017468-E -

Cabins of black cooperative farmers were on one side of the road, cabins of white farmers were on the other side. June 1937 Dorothea Lange photograph courtesy Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Farm Security Administration and Office of War Information Collection. Call No. LC-USF34-017339-C. -

Cabins at the Delta Cooperative Farm. Screen windows and porches were uncommon in cotton farm cabins. June 1937 Dorothea Lange photograph courtesy Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Farm Security Administration and Office of War Information Collection. Call No. LC-USF34-017356-C. -

Worker in community garden which supplied fresh vegetables to twenty-eight families at the Delta Cooperative Farm, Hillhouse, Mississippi. June 1937 Dorothea Lange photograph courtesy Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Farm Security Administration and Office of War Information Collection. Call No. LC-USF34-017354-C. -

Community house at Delta Cooperative Farm. This building housed the library, school, clinic, and meeting room. June 1937 Dorothea Lange photograph courtesy Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Farm Security Administration and Office of War Information Collection. Call No. LC-USF34-017484-E.

Selected Bibliography:

Campbell, Will. Providence. Atlanta, Georgia: Longstreet Press, Inc., 1992.

Conrad, David Eugene. The Forgotten Farmers: The Story of Sharecroppers in the New Deal. Ithaca, New York: Thomas Y. Crowell Company, 1967.

Dallas, Jerry W. “The Delta and Providence Farms: A Mississippi Experiment in Cooperative Farming and Racial Cooperation, 1936-1956.” Mississippi Quarterly 4 (1987): 283-308.

Daniels, Jonathan. A Southerner Discovers the South, 1901-1969. New York: Macmillan Company, 1938.

Holley, Donald. Uncle Sam’s Farmers: The New Deal in the Lower Mississippi Valley. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1975.

Kester, Howard. Revolt Among the Sharecroppers. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 2002.

Smith, Fred C. “Agrarian Experimentation and Failure in Depression Mississippi: New Deal and Socialism, the Tupelo Homesteads and the Delta and Providence Cooperative Farms.” M. A. Thesis, Mississippi State University, 2002.