In March 1933, a tall, lanky, sandy-haired man stepped off the train at the Washington, D. C. station. No one greeted him, no band played, hardly anyone knew he had arrived. William M. Colmer had come to the nation’s capital to witness the inauguration of Franklin D. Roosevelt and then to represent the people of the sixth congressional district of Mississippi in the Seventy-third Congress.

Colmer also had come to Washington in the midst of the Great Depression. And he voted like a New Deal Democrat. He proudly told this writer in 1972 he was not a New Dealer, yet the record reveals he voted for every New Deal measure except one, including the Fair Labor Standards Act, which established the minimum wage.

How do we explain this New Deal voting record from a man generally viewed as an ultra-conservative when he left Washington forty years later? Colmer understood he had to support his party in order to gain leadership positions. He supported the Democratic party, and Democratic congressional leaders rewarded him with an appointment to the important Rules Committee in 1939. In time, he became its chairman.

The Great Depression

Colmer also understood that Mississippi and the nation faced the greatest depression in its history and that the depression created special problems that required emergency action by the federal government.

When Colmer took his seat in Congress in 1933, Mississippi and the nation were struggling with an economy stagnated beyond belief. Unemployment was at an unprecedented high. Jobs were virtually non-existent. Banks failed daily. Prices of farm products fell to an all-time low. People waited patiently in soup lines for a handout of food. Families lost their homes and businesses because they could not pay their property taxes.

According to an article in The Literary Digest, a national news magazine, on a single day in April 1932 one-fourth of the real property in Mississippi, including 20 percent of all farms and 15 percent of town property, went under the auctioneer’s gavel and was sold to pay taxes. The sales, conducted by 74 sheriffs, included about 40,000 farms. Most of the property went to the state of Mississippi which already owned about one million acres.

Letters Describe Plight

In supporting New Deal legislation, Colmer was also influenced by his constituents who wrote him thousands of letters describing their plight, giving him their views on all issues before the Congress, and imploring him to influence the federal government to solve their problems. Letters came from rich, poor, Black people, White people, male, female, young, old, educated, uneducated, professionals, farmers, laborers, and businessmen.

As you will see, some letters were well-written; others with their incorrect grammar, punctuation, and spelling, paint a portrait of the educational level of our citizens in the 1930s and suggest a desperate need for educational reform. Yet, educated or not, constituents made their views known to Colmer. He read their letters and responded. Included in the selection of constituent letters reprinted here are a few letters from Colmer as examples of his attempt to assist.

The letters come from the Colmer Papers in the William D. McCain Library at the University of Southern Mississippi. Except in a few instances where words were added in brackets, the letters were not edited. Their spelling, grammar, and punctuation were left intact. The only change is that the writers’ names were replaced with their initials. Let the letters speak for themselves. Read the letters.

Mississippians wrote Congressman Colmer hundreds of letters during the depression. They also wrote their other congressmen and senators, President Franklin D. Roosevelt, and the numerous New Deal agencies. What can we learn and conclude from these letters? Undoubtably, Mississippians suffered severely from the depression. Without jobs and money they could not purchase the basic necessities, including food and clothing.

Social Security Act

Most Mississippians did not feel alienated from their government, but believed that it could and should solve their economic problems and free them from their poverty and misery. In their letters, they particularly urged Washington to provide immediate relief, jobs, and an old-age pension. President Roosevelt and the New Deal did respond with relief funds, numerous job programs, and the Social Security Act of 1935.

These programs did mitigate the suffering of many Mississippians, but not all. Job relief programs were not adequate, never remotely close to the demand for jobs. As a result, many Mississippians remained jobless throughout the depression.

Mississippians who wrote Congressman Colmer saw and experienced little improvement in the economy until 1940. World War II changed Mississippi’s economy forever by bringing industry and jobs and ushering in an unparalleled prosperity. In the war years, many Mississippians earned more money in a week than they had earned in a year during the depression.

Prosperity, however, did not visit all Mississippians. People who were too old to work or physically unable to work continued to suffer economic hardship. The Social Security Act scarcely benefited older Mississippians. Benefits under the original act bear little resemblance to benefits under social security today. The original act provided for a maximum pension of $30 a month based on a 50 percent federal-state match of funds to people over sixty-five.

Moreover, the law gave each state the power to decide eligibility requirements and the monthly payment to recipients. The payment of maximum benefits to all Mississippians over sixty-five in 1935 would have cost almost as much as the entire Mississippi budget for the year.

Mississippi, therefore, limited payment to paupers — those people who owned nothing and who had no means of support whatsoever. Not only did this limit severely restrict eligibility, but even those Mississippians drawing pensions only received an average monthly payment of around $6.40 a month in 1940 and around $9.00 a month in 1944 at a time when the price of goods rose drastically.

As the last letter writer, Mr. C. A. P., stated, many old people did not enjoy the prosperity of World War II and struggled to survive. Continued pressure in the following decades by senior citizens would ultimately lead to significant improvements in social security benefits.

Kenneth G. McCarty, Ph.D., is professor emeritus of history, University of Southern Mississippi, and a member of the Editorial Advisory Board for Mississippi History Now.

Lesson Plan

-

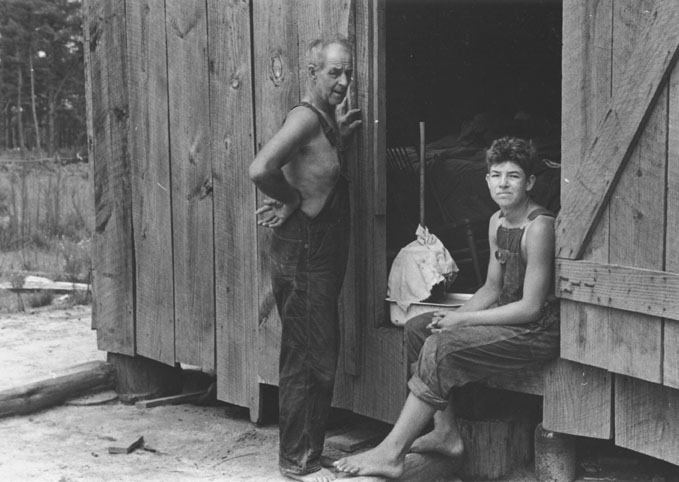

Mississippi father and son. 1935 Farm Security Administration (FSA) photograph by Arthur Rothstein. Courtesy of Mississippi Department of Archives and History. -

Mississippi sharecropper's daughter. 1935 FSA photograph by Arthur Rothstein. Courtesy of Mississippi Department of Archives and History.

-

Mississippi mother and children. FSA photograph by Dorothea Lange. Courtesy of Mississippi Department of Archives and History. -

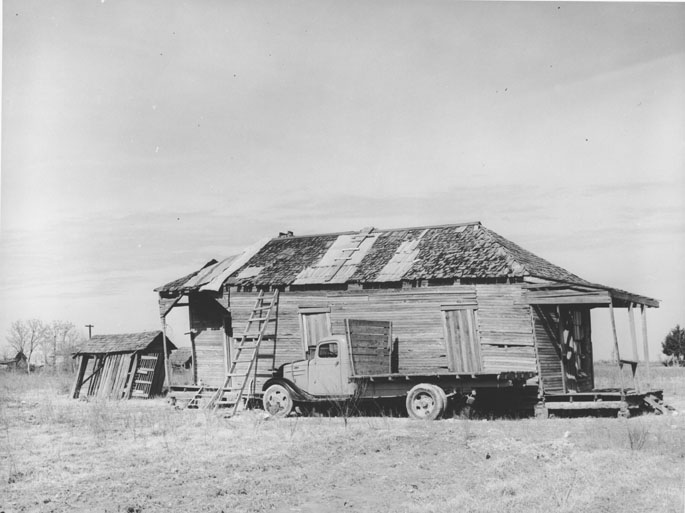

Mississippi house. FSA photograph by Marion Post Wolcott. Courtesy of Mississippi Department of Archives and History. -

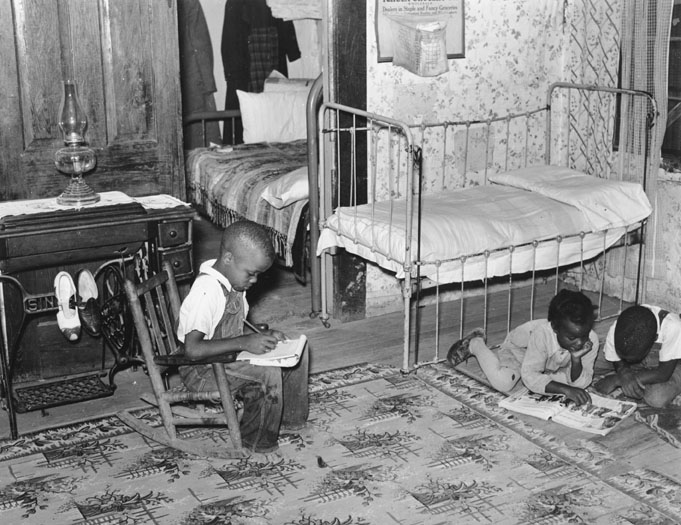

Mississippi cabin with children. FSA photograph by Marion Post Wolcott. Courtesy of Mississippi Department of Archives and History.

Sources

William M. Colmer Oral History. Interview by Kenneth G. McCarty, 1973. William D. McCain Library, University of Southern Mississippi, Hattiesburg, Mississippi.

"One-Fourth of a State Sold for Taxes," The Literary Digest, 93 (May 7, 1932), 10.