The land that became the state of Mississippi had been claimed by European powers for nearly a century prior to it first coming under American jurisdiction. Between the late 1600s and the late 1700s, France, Great Britain, and Spain each established extensions of their respective colonial empires within the region. During these efforts they attempted to form political, military, and economic alliances with the area’s original inhabitants, including the Choctaw and Chickasaw peoples and numerous smaller tribal entities. Beginning in 1798 with the establishment of the Mississippi Territory, however, the area’s long and complex colonial era began to draw to a close.

Over the next roughly two decades, the area that would become Mississippi experienced a long and winding path towards statehood as a part of the United States. This era featured international controversy, the arduous establishment of an American government, a flood of immigration, a bitter war, the growth of slavery, and a divisive path towards statehood all along a backdrop of Native Nations clinging to their way of life. These events remain significant today for their importance in understanding both the state’s founding and their influence in shaping much of Mississippi’s early development.

End of the European era

Spain, the last European power to control the region, signed the Treaty of San Lorenzo (Pinckney’s Treaty) in 1795 in which it recognized the 31st parallel as the boundary between Spanish Florida and the United States. This compact finally cleared the way for American settlement north of that line after years of disagreement. Spanish officials had second thoughts almost immediately after signing the treaty, and for over two years presented numerous excuses for not evacuating the area. Making this tense situation worse was Andrew Ellicott, who the United States sent to participate in the joint survey of the 31st parallel required by the treaty. Ellicott took upon himself the unauthorized responsibility for establishing American control and maintaining order. Unfortunately, he lacked the necessary diplomatic skills to interact with Spanish officials, and open conflict almost resulted on numerous occasions. Finally, after numerous delays, the Spanish relinquished control of the area in March 1798.

Creation of the Mississippi Territory

Less than a month later, on April 7, 1798, Congress created the Mississippi Territory. The territory’s original boundaries consisted of the region bounded by the Mississippi and Chattahoochee rivers in the west and east, the 31st parallel in the south, and the point where the Yazoo River emptied into the Mississippi River in the north. The territory expanded twice over the next two decades. In 1804, the northern boundary was extended to the Tennessee state line, and in 1812, President James Madison annexed additional land along the Gulf of Mexico Coast. By 1813, the Mississippi Territory encompassed the boundaries of present-day Alabama and Mississippi.

Government for this new territory was patterned after the 1787 Northwest Ordinance, which established a governor, secretary, and three judges to serve as a ruling council. After the territory’s population reached 5,000 free adult males, an assembly could be elected and a delegate sent to Congress. One significant difference from the laws of the Northwest Territory was that slavery was allowed.

The new government faced a variety of difficult issues: conflicting land claims, tense relations with Chickasaws and Choctaws, and the continuing interference of the Spanish. First of all, France, England, Spain, and the state of Georgia had all issued overlapping land grants in the region and the new government had to sort out these disputes. Second, most of the territory was inhabited by Native Americans who were apprehensive after their ally Spain abandoned them to the ever-expanding United States. The new government would have to maintain peace between these peoples and land-hungry immigrants. Finally, Spanish officials in West Florida and Louisiana posed a potential threat to the security of the region.

Factionalism in the territorial government

Severe political factionalism came to characterize territorial politics and served to hamper the Mississippi Territory’s governors as they attempted to deal with these problems. The administration of Governor Winthrop Sargent, the first of the territory’s four governors, set the tone for the contentious political environment in which the territorial government would function. A Massachusetts-born Federalist, Sargent had an autocratic style that clashed immediately with the independent frontiersmen of the region. Many viewed his attempts to bring law and order to the territory, especially his series of laws derisively known as “Sargent’s Codes,” as usurpations of power. In 1799, his opponents secretly sent a representative to the nation’s capital to present their grievances to the federal government. As a result of these appeals, the government granted the second stage of territorial status to Mississippi, which featured popular election of officials. Sargent was soon removed from office by Thomas Jefferson, the newly elected Democrat-Republican president. The territory’s new administration repealed all of Sargent’s laws and moved the territory’s capital from Federalist-dominated Natchez to nearby Washington.

Sargent’s removal, however, did not end the fierce factionalism that defined the period. The three governors who followed him would all struggle to maintain harmony between the territory’s bitter antagonists who fought over a wide variety of issues and continually sought ways to change the structure of the government in their favor. It was not until near the end of the territorial period, under the direction of Governor David Holmes, that the political rivalry began to subside. By that time, most of the leading “troublemakers” had passed away, and the majority of the area’s residents became focused on the drive for statehood.

Settlement of the Mississippi Territory

The residents of the Mississippi Territory were primarily former British or Spanish citizens or natives of other parts of the United States who had migrated to the region in pursuit of land and opportunity. This great migration occurred in two distinct waves. The first wave occurred between 1798 and 1812 when the Territory’s population increased from about 10,000 to just over 30,000. Following the conclusion of the Creek War in 1814, a flood of immigration into the region occurred. By the time of Mississippi’s statehood in 1817, the area’s population had swelled to over 200,000, more than one-third of whom were enslaved people

While the territory remained overwhelmingly rural, it included several noteworthy towns such as Washington, Port Gibson, Columbia, Winchester, Mobile, and Huntsville. Natchez was by far the most important town in the territory. Laid out by the Spanish in the late 1700s, the city became the cultural and economic center of the territory as well as the seat of political power throughout the period.

Life in the Mississippi Territory

Whether they lived in a city or in the countryside, the lives of most residents of the Mississippi Territory revolved around agriculture. Cotton became by far the most profitable and important crop. Much of the land in the Mississippi Territory was ideally suited for its production, and thousands of settlers came to the region to take advantage of the situation. Numerous improvements to the cotton gin, the invention of the cotton press, and the introduction of a variety of cotton uniquely suited to the local environment also helped ensure the crop’s dominance in the economic life of the region.

Just as importantly, the profitability of cotton production gave rise to the widespread growth of slavery in the Mississippi Territory. Enslaved people had first been brought into the region during the colonial era, but it was during the territorial period that their population grew in significant numbers. Between 1798 and 1817, the enslaved population in the Mississippi Territory increased from approximately 4,000 to about 70,000. Most were brought in from elsewhere in the South by planters or purchased at slave markets. The institution exerted great influence on the territory’s economy and laid the foundation for a pattern of economic and social development that would dominate much of Mississippi’s history for the next fifty years.

While planters prospered, public education and organized religion struggled to gain a foothold. Since there were few publicly funded schools in operation during the territorial period, wealthy citizens either hired private tutors to teach their children or sent them to private academies or eastern schools. Although Jefferson College was chartered in 1802, private literary and scientific societies took the lead in encouraging appreciation of academic and cultural pursuits.

While many of the churches that would figure prominently in the state’s history were first established during this era, it is estimated that only about five percent of Mississippi’s population were members of a church at the time of statehood. Many territorial residents were more familiar with camp meetings than with traditional church ceremonies. At these large-scale events in wilderness clearings, frontier preachers exposed thousands to religious teachings.

The Creek War

No other event affected the development of the region more than the Creek War. The war began as a civil war within the Creek nation over the issue of assimilation into American civilization versus retaining traditional Creek culture. Fighting between American troops and Red Stick Creeks, who opposed the increasing American influence in the area and advocated for traditional Indian practices, first broke out in the summer of 1813. The war escalated a month later when Red Sticks successfully attacked Fort Mims, located north of Mobile, killing over 250 settlers and soldiers in the process. News of the killings spread like lightning across the nation. Thousands of American troops, assisted by numerous Native American allies, soon converged on the area to respond to the assault on Fort Mims.

Throughout the fall of 1813 and spring of 1814, the Creek War raged across the Mississippi Territory. On March 27, 1814, General Andrew Jackson won the climactic Battle of Horseshoe Bend which finally destroyed the Red Sticks as a military power. In the chaos, roughly 900 Native Americans were killed, more than in any other battle in American history. The subsequent Treaty of Fort Jackson forced the devastated Creeks to cede over twenty-three million acres of land to the United States and cleared the way for an influx of immigration into the Mississippi Territory.

Division of the Territory

Arguments over whether the Mississippi Territory would enter the union as one state or two had begun almost immediately after its organization in 1798. Aware of the economic and political dominance of their portion of the territory, many western residents, specifically those in the Natchez District, favored admission as a single state so that they might maintain their influence. Many eastern residents in the Mobile region, however, initially felt that their interests were neglected due to the great distance between themselves and the territorial capital as well as other inherent differences in economy and lifestyle. After the Creek War, however, the situation reversed. The population of the eastern section of the territory (today’s state of Alabama) grew rapidly as settlers migrated onto the rich agricultural land formerly occupied by the Creek Indians. Realizing the potential to exert more influence on any new state of which they were to be a part, many eastern section residents now began to favor admission of the territory as one state. Sensing the future diminishment of their influence, those in the western section (today’s state of Mississippi) now advocated division into two states.

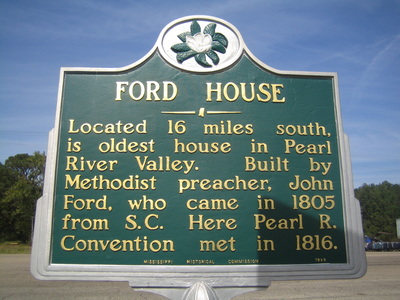

In October of 1816, many prominent residents from throughout the territory met at the home of John Ford, south of Columbia, to discuss the issue. In what became known as the “Pearl River Convention,” the attendees, overwhelmingly eastern section residents, decided to send leading territorial official Harry Toulmin to the nation’s capital to request admission of the territory as a single state.

Mississippi achieves statehood

Mississippi Territorial delegate to Congress William Lattimore was already working towards statehood when the convention’s resolution arrived in Washington, D.C. Finding it impossible to follow the contradictory opinions of all of the territory’s citizens, he decided to request division in large part because he knew that southern senators would welcome the creation of four new pro-slavery seats in the Senate instead of just two. Lattimore’s argument ultimately triumphed over Toulmin’s efforts, and President James Madison signed the enabling act that granted admission of the western section of the territory as the state of Mississippi on March 1, 1817; the eastern section was organized as the Alabama Territory at the same time. The line of division, which still serves as the boundary between Mississippi and Alabama today, was designed to be a compromise between the wishes of western and eastern residents of the territory.

In July of 1817, forty-eight delegates from Mississippi’s fourteen counties met at the town of Washington, near Natchez, to draft the new state’s constitution. The constitution established Mississippi’s government and recognized Natchez as the state’s capital. With the last requirement for statehood completed, President James Monroe on December 10, 1817, signed the resolution that admitted Mississippi as the nation’s twentieth state. Territorial governor David Holmes won election as the state’s first governor. Electors also chose George Poindexter as its only congressman and Walter Leake and Thomas H. Williams as its first senators. Alabama entered the Union two years later in 1819.

In less than two decades, Mississippi had evolved from a sparsely inhabited frontier region to a dynamic part of the American union. Its population and influence would grow exponentially as it matured in the coming years (with enslaved people eventually outnumbering Whites) and assumed its position at the heart of the economic, social, and political development of the Deep South. Though brief, Mississippi’s territorial period laid the foundation for the state’s early growth, established slavery as central to the state’s economy, and is crucial to understanding the state’s past.

J. Michael Bunn is the director of the Historic Blakeley State Park in Alabama, and Clay Williams is the sites administrator with the Mississippi Department of Archives and History. This article was updated in 2021.

-

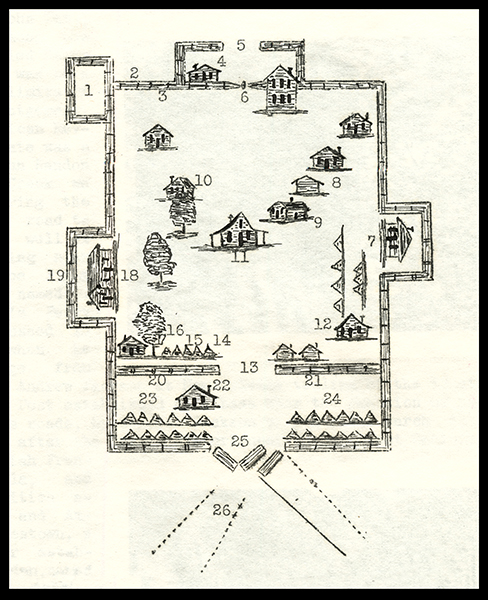

The Mississippi Territory. Map modeled after J.T. Adams, Atlas of American History, (1943). -

Map of the Mississippi Territory in 1816 created by Fielding Lucas. Courtesy Mississippi Department Archives and History.

-

Winthrop Sargent of Massachusetts, the first governor of the Mississippi Territory, arrived in Natchez in 1798. Courtesy Mississippi Department of Archives and History. -

The Old Natchez Trace. The Trace was an important frontier artery for travelers, settlers, and merchants. Courtesy Mississippi Department of Archives and History, PI/1996.0018, No. 10. -

David Holmes was the fourth governor of the Mississippi Territory and the first governor of the State of Mississippi. Courtesy Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, LC-USZ6-683. -

Connelly's Tavern on Ellicott Hill in Natchez. Here, Andrew Ellicott, in defiance of Spanish authority, raised the American flag for the first time in the Lower Mississippi Valley in 1797. Courtesy Mississippi Department of Archives and History, PI/CI/N38.3, No. 66. -

This diagram of Fort Mims was based on drawings found in the papers of Gen. Ferdinand L. Claiborne, who fought in the Creek War of 1813-14. The numbers were added in the modern period: 6 and 26 are the locations of the gates through which the Red Sticks entered the fort. The rest of the numbers indicate locations of various settler homes and military buildings and fort features. Courtesy of the Alabama Department of Archives and History. -

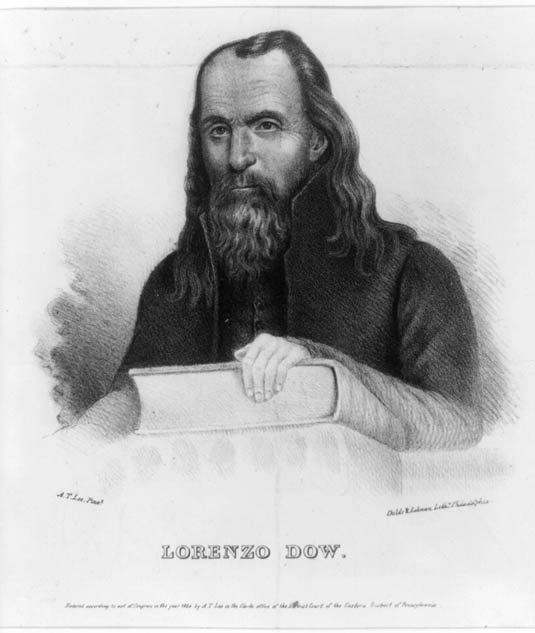

Lorenzo Dow, one of the most famous religious leaders of his day, was responsible for some of the first camp meetings held in the Mississippi Territory. Courtesy Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, LC-USZ62-28013. -

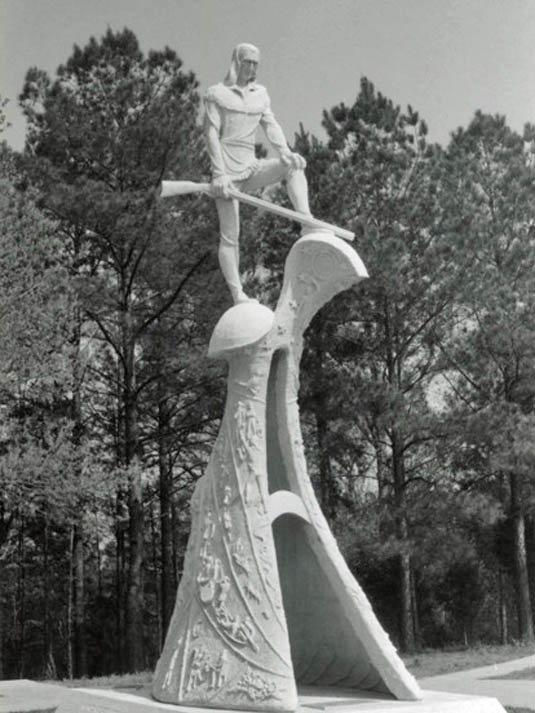

Samuel Dale (1772-1841), frontier pioneer, was one of the prominent residents at the "Pearl River Convention." He later settled in Mississippi and was elected a state representative from Lauderdale County. The Sam Dale statue is located in Daleville, Mississippi. Courtesy Mississippi Department of Archives and History, PI/PA/1981.0080, No. 4. -

On October 29, 1816, county delegates chosen by vote during local meetings of settlers gathered at the Ford Home to discuss the issue of statehood at what became known as the Pearl River Convention. Its primary purpose was to express to Congress support for admission of the Mississippi Territory as one state, not two. Image courtesy http://www.mississippimarkers.com. -

The restored Ford House has been open to the public since June 1963. In 1971, the site was placed on the National Register of Historic Places. Image courtesy http://www.mississippimarkers.com.

Bibliography

Bettersworth, John K. Mississippi: A History. Austin: The Steck Company, 1959.

Busbee, Jr., Westley F. Mississippi: A History. Wheeling, Illinois: Harlan Davidson, Inc., 2005.

Carter, Clarence Edward, ed. The Territorial Papers of the United States, vols. 5-6, The Territory of Mississippi, 1798-1817. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1937-38.

Claiborne, J.F.H. Mississippi as a Province, Territory and State, with Biographical Notices of Eminent Citizens, Vol. 1. Jackson: Power & Barksdale, Publishers and Printers, 1880.

Gonzales, John Edmond, ed., A Mississippi Reader: Selected Articles from The Journal of Mississippi History. Jackson: Mississippi Historical Society, 1980.

Haynes, Robert V. “The Formation of the Territory,” in A History of Mississippi, edited by Richard Aubrey McLemore, Vol. 1. Jackson: University & College Press of Mississippi, 1973, 174-216.

Haynes, Robert V. “The Road to Statehood,” in A History of Mississippi, edited by Richard Aubrey McLemore, Vol. 1. Jackson: University & College Press of Mississippi, 1973, 217-250.

Haynes, Robert V. “Territorial Mississippi, 1798-1817,” Journal of Mississippi History, 2002, Vol. 64, pp. 283-315.

Rowland, Dunbar. History of Mississippi: The Heart of the South, Vol. 1. Chicago: S.J. Clarke Publishing Company, 1925.

Rowland, Dunbar, ed. The Mississippi Territorial Archives, 1798-1803, Executive Journals of Governor Winthrop Sargent and Governor William Charles Cole Claiborne, Vol. 1. Nashville: Press of Brandon Printing Company, 1905.

Skates, John Ray. Mississippi, A Bicentennial History, New York: W.W. Norton & Company, Inc, 1979.