Mississippi public schools underwent a dramatic change in 1970. After sixteen years of delays and token desegregation after U. S. Supreme Court orders to dismantle the state’s dual school system, a steady stream of legal action by Black parents and federal intervention toppled the state’s ninety-five-year-old “separate but equal” educational system in which White school children went to one school system and Black school children went to another one. During and after the change to a unitary school system that would allow White and Black children to attend the same schools, state and federal officials declared the process an unqualified success. Mississippi’s state superintendent of education said in triumph in the summer of 1970 that the state now had the most desegregated schools in the nation.

By the fall of 1970, all school districts had been desegregated, compared to as late as 1967 when one-third of Mississippi’s districts had achieved no school desegregation and less than three percent of the state’s Black children attended classes with White children. And this transformation was generally accomplished across the South without the violence associated with the earlier desegregation and voting rights battles of the 1960s.

Yet massive White resistance in Mississippi to the United States Supreme Court’s Brown vs. Board of Education decision in 1954 continued to thrive in 1970 and decisively undermined the possibility of creating a truly integrated school system. (The Brown decision ruled that segregation in public schools was prohibited by the U. S. Constitution. The decision overturned the Court’s ruling in the 1890s that had allowed southern states to establish “separate but equal” educational systems for Black and White people.)

The integration of Mississippi public schools that occurred in 1970 represented but another chapter in the long battle over public school desegregation in the state. For many years following the end of Reconstruction in 1875, the demands of Black Mississippians for better schools went virtually ignored, but by the end of World War II in 1945 the state began to make some efforts to equalize Black and White school facilities. Mississippi, however, one of the nation’s poorest states since the end of the American Civil War, had never had the resources to finance one school system adequately, much less two. Nevertheless, in the late 1940s and early 1950s before the Brown decision, Mississippi leaders finally invested large sums of money in an effort to make separate schools truly equal in order to avert possible legal challenges to segregation on the basis of funding discrepancies, quality of facilities, materials, etc. But it was too late. Making up the difference would take decades and more money than the state had available.

Supreme Court rules

After the passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, state and local officials reluctantly adopted the freedom-of-choice method of school desegregation, which essentially stated that any student could choose to go to any school in a school district. Mississippi used this mechanism to keep largely segregated schools while allowing token desegregation and maintaining the private- and state-sanctioned terror against African American citizens who pressed for further school integration.

In 1968, the U. S. Supreme Court ruled, in Green vs. County School Board, that freedom of choice had proved ineffective and was no longer an acceptable method of school desegregation. A year later, the Supreme Court in a landmark decision, Alexander vs. Holmes, which spoke directly to thirty school districts in Mississippi but ultimately to the entire South, ordered the immediate termination of dual school systems and the establishment of unitary systems.

The official White response in Mississippi to the Green and Alexander decisions echoed the response to the original Brown decision: state leaders became dedicated converts to the approach recently outlawed and proclaimed their desire to proceed with freedom-of-choice desegregation. Mississippi and other southern leaders clearly recognized the rhetorical value of the phrase, “freedom of choice.” A Mississippi representative told the U. S. House of Representatives that “freedom of choice is the only way to save quality public education. Freedom of choice – what can be more American? Or more democratic?”

State officials also argued that the federal courts had pushed Mississippi and other southern states on the school desegregation issue far beyond any constitutional mandate. In a sense, Mississippi political leaders were right; the Supreme Court’s latest decisions had gone beyond both the Brown decision and the Civil Rights Act of 1964 by calling for a results-oriented remedy that required evidence of racial balance. Also, since segregation in the North had been established by custom rather than by law, northern schools would seemingly escape the implications of this latest mandate. What the scripts of Mississippi politicians refused to acknowledge, however, was that the state’s resistance to all attempts to end the dual school system – including the freedom-of-choice plan – had led the court to impose a results-oriented test.

Freedom of choice

Mississippi leaders often claimed that the freedom-of-choice mechanism led to limited desegregation simply because African Americans did not choose to go to White schools – something of a partial truth. Seeking better resources for Black education, many Black parents – with help from civil rights organizations such as the Delta Ministry, the American Friends Service Committee, the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, and others – did take the often difficult step of choosing a White school for their children. But the freedom-of-choice strategy for achieving school desegregation implied that people actually had the freedom to choose. In much of the South, most Black people did not. In Mississippi between 1964 and 1969, Black parents who chose White schools for their children were regularly intimidated in myriad ways, and the handful of Black students who actually entered White schools under the freedom-of-choice system often faced the wrath of generally unsympathetic White teachers and students.

Freedom of school choice proved essentially meaningless as a mechanism for ending school segregation, a fact that may largely explain why Mississippi leaders persisted in promoting the remedy after the courts ruled it invalid. They continued the sixteen-year-old crusade to circumvent the Brown requirement to dismantle the state’s dual school system. Many believed that even the most recent obstacles to preserving segregated schools could eventually be overcome.

White protests

As the early 1970 deadline approached for implementing the Alexander decision, White Mississippians adopted a variety of strategies in an effort to dodge the ruling:

White parents adopted the tactics of the civil rights movement, organizing protest marches, mass rallies, student boycotts, and sit-ins at White schools to protest the recent desegregation orders. White parents and other White opponents of school integration claimed they did not oppose desegregation; they only feared the destruction of neighborhood schools through mechanisms such as busing. A Taylorsville man told President Richard Nixon, “I would not object to my child going to school if it was integrated by ‘freedom of choice’ but for him to be picked up and bussed across the county I will not do.” Though Nixon generally supported such sentiments, which White parents across the nation would echo in a few short years, these anxieties of White Mississippians really had little to do with busing. Indeed, in a largely rural state, most school districts had bused the vast majority of their students for years. The real institution White parents in Mississippi sought to preserve was the White neighborhood school.

Private academies

Whites in the Delta and many other Black-majority school districts in Mississippi came to see abandonment of the public schools for often hastily organized private segregation academies as the only way to preserve “quality” White education. Mississippi Governor John Bell Williams sympathized, but along with most state politicians and business leaders, recognized that abandoning public schools permanently would damage the state’s continuing efforts to attract industry to the state. Between 1966 and 1970, however, the number of private schools in the state rose from 121 to 236, and the number of students attending these schools tripled; most of this growth occurred in Black-majority districts. Fewer White families fled from public schools in White-majority districts.

Though White families abandoned public schools in droves in many Black-majority districts, they did not relinquish control over these schools. In some locales, the newly enfranchised Black population had succeeded in electing a Black school board member or two, but even there, White leaders sometimes thwarted Black participation. Most districts, however, had appointed board members, and White leaders continued to control school systems that neither their children nor those of their White neighbors attended. As a result, they had little incentive to make the improvements to Black education already long postponed.

Segregate within desegregated

The easiest way to accede to the Alexander mandate without relinquishing segregation, of course, was simply to segregate students by race within desegregated schools. For example, at DeKalb High School, Black and White students attended classes in separate wings of the same building, changed classes at different times to the sounds of a “black” bell and a “white” bell, ate lunch at different times, and even drank water from separate fountains. Civil rights leaders quickly and successfully attacked such obvious evasions of the mandate for unitary schools, but other more subtle attempts to continue segregation within “desegregated” schools proved more difficult to eradicate. Grouping of students by abilities became perhaps the most pervasive segregation practice after the integration of schools. And school desegregation plans often called for the closing of Black schools or the alteration of their identities as Black schools in order to allay White fears about their children going to schools in Black neighborhoods.

In the end, most Black and White Mississippians could at least agree that the attempt to integrate the state’s school system in 1970 was generally a failure. Looking back on the transition from the vantage point of 1974, Harry Bowie, who had worked with the Delta Ministry, summed up the problem: “We’ve massively integrated the school system in Mississippi. … We have not accomplished massive integration in the truest sense. We still have a great deal to do on that front.”

Charles C. Bolton, Ph.D., is professor and head of the history department at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro, and the author of “The Last Stand of Massive Resistance: Mississippi Public School Integration, 1970,” which appeared in Winter 1999 edition of The Journal of Mississippi History, Volume LXI, No. 4, and from which this article is condensed. Bolton is also the author of The Hardest Deal of All: The Battle Over School Integration in Mississippi, 1870-1980, published by the University Press of Mississippi, 2007.

Lesson Plan

-

Circa 1895. School for white students in Walthall County, Mississippi, (probably in Tylertown). Courtesy Mississippi Department of Archives and History, PI/ED/1983.0003, No. 12. -

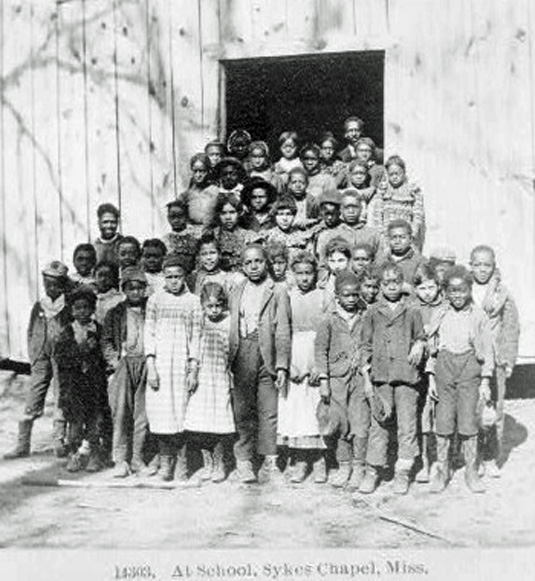

1901. Black children posed outside their school at Sykes Chapel, Mississippi. Courtesy Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, LC-USZ62-113945.

-

February 1916. Public school for white students in Pass Christian, Mississippi. Courtesy Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, LC-DIG-nclc-01032. -

Constructed in 1924. School for white students in Monticello, Mississippi. Monticello High School photograph circa 1960. The building is now the Lawrence County Civic Center & History Museum. -

1937. School for black students is located in the center of a plantation in the Mississippi Delta. Dorothea Lange photograph courtesy Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, LC-USF34-017520-E. -

1939. Interior of black school in the Mississippi Delta. Marion Post Wolcott photograph courtesy Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, LC-USF34-052319-D.

Selected Bibliography:

Dittmer, John. Local People: The Struggle for Civil Rights in Mississippi. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1994.

McMillen, Neil. Dark Journey: Black Mississippians in the Age of Jim Crow. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1989.

–––––––– The Citizens’ Council: Organized Resistance to the Second Reconstruction, 1954-1964. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1971.

Nixon, Richard. RN: The Memoirs of Richard Nixon. New York: Grosset & Dunlap, 1978.

Payne, Charles. I’ve Got the Light of Freedom: The Organizing Tradition and the Mississippi Freedom Struggle. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995.

Reed, Frank and Lucy McGough. Let Them Be Judged: The Judicial Integration of the Deep South. Methuchen, N.J.: Scarecrow Press, 1978.

Taylor, Jared. Paved with Good Intentions: The Failure of Race Relations in Contemporary America. New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers, 1992.

Mississippi Department of Archives and History, subject files.