“We Stood firm to the union when secession Swept as an avalanche over the state. For this cause alone we have been treated as savages instead of freeman by the rebel authorities.”

Newton Knight, Petition to Governor William Sharkey, July 15, 1865

Newton Knight was born in 1837 near the Leaf River in Jones County, Mississippi, a region romantically described in 1841 by the historian J.F.H. Claiborne as a “land of milk and honey.” The landscape was dominated by virgin longleaf pines. Wolves and panthers still roamed the land.

Knight married Serena Turner in 1858 and they moved to the edge of Jasper County to set up a homestead where they grew corn and sweet potatoes, and raised hogs and cattle. Fruits, berries, and wild game added variety to their diets. Newt worked hard and tilled the land himself. According to his son, Newt never drank or cursed, was a Primitive Baptist, and doted on his children. He would become a man of myth and legend.

Soon after the election of Abraham Lincoln as United States president in November 1860, slave-owning planters led Mississippi to join South Carolina and secede from the Union in January 1861. Other southern states would follow suit. Mississippi’s Declaration of Secession reflected the planters’ interests in the first sentence: “Our position is thoroughly identified with the institution of slavery ….” However, the yeoman farmers and cattle herders of Jones County had little use for a war over a “state’s right” to maintain the institution of slavery. By 1860, enslaved peoples made up only 12 percent of the total population in Jones County, the smallest percentage of any county in the state.

Opposition to Civil War

In April 1861 the American Civil War began. Many Mississippians, including Newt Knight, were opposed to secession and war. They viewed the rebellious Confederate government as the invading body. But the state was swept up in war-fever, and those who opposed the new Confederate government were labeled cowards or traitors. All across Mississippi, the opponents of the Confederacy were often persecuted in what witnesses described as “… a reign of terror … Many are forced into the army, instant death being the penalty in case of refusal, thus constraining us to bear arms against our country ….” Under these circumstances, Knight reluctantly enlisted in the Confederate Army in the early fall of 1861. He had only served for a few months when General Braxton Bragg furloughed him to go home to attend to a pressing family matter. Newt’s father, Albert Knight, was dying.

Then, on May 13, 1862, Newt Knight enlisted as a private with his friends and neighbors into Company F of the Seventh Battalion, Mississippi Infantry in Jasper County. They enlisted together so they could avoid being drafted away to serve with strangers. After the war, Newt claimed that he only agreed to serve as an orderly to care for the sick and wounded.

Meanwhile, the Confederate Congress had passed the infamous “Twenty-Negro Law,” which allowed planters who enslaved twenty or more people to be exempt from fighting. Newt’s friend and comrade, Private Jasper Collins, was furious: “This law … makes it a rich man’s war and a poor man’s fight.” Collins threw down his weapon and left the Confederate Army for good. Collins would later name a son Ulysses Sherman Collins in honor of his favorite Union generals, Ulysses S. Grant and William Tecumseh Sherman. Not long after Collins left the army, Newt learned that back home the Confederate cavalry had seized his family’s horses. In early November 1862, Newt went AWOL, or Absent Without Leave, near Abbeville, Mississippi, and began the dangerous 200-mile journey back to Jones County. Along the way he had to avoid capture by the Confederate patrollers who searched the roads for deserters.

Newt was shocked by the condition of the people on the home front. With so many men away fighting the war, the farms were run-down and crops had failed for lack of labor. The women of Jones, Jasper, and Smith counties were struggling to feed their hungry children. Even worse, the Confederate authorities had imposed the hated “tax-in-kind” system in which tax collectors took what they wanted for use by the Confederate armies. They took meat from the smokehouses. They took horses, hogs, chickens, and corn. They took cloth the women had saved to make clothes for the children. Confederate Colonel William N. Brown reported that the corrupt Confederate tax officials had “done more to demoralize Jones County than the whole Yankee army.” A planter in neighboring Smith County warned Governor John J. Pettus in November 1862, “If something is not done by the legislature to open the corn cribs that are now closed against the widow and the orphan, and soldier’s families, who are destitute, I know that we are undone. Men cannot be expected to fight for the Government that permits their wives and children to starve.”

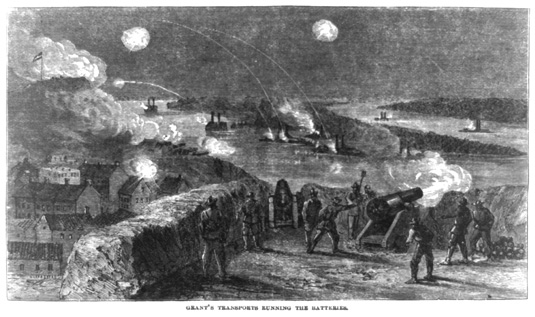

In May 1863, the Seventh Battalion was rushed into the Battle of Vicksburg. When Newt refused to go back into the Confederate Army, he was arrested and taken prisoner. His friends later testified that the Confederate authorities tortured Newt and destroyed everything he owned, including his horses and mules, which “left his family destitute.” During the six-week siege of Vicksburg, the Confederate soldiers were trapped in a chamber of horrors. One Jones County soldier walked home after the Confederate defeat at Vicksburg only to find that his wife had starved to death. She had given every last morsel of food to the children. After the fall of Vicksburg in July 1863, many Confederate soldiers deserted and came back to Jones County.

In August 1863, Confederate Major Amos McLemore was sent to round up the deserters. However, on October 5, 1863, McLemore was shot and killed in the home of Amos Deason in Ellisville, Mississippi. Most people believed that the man who pulled the trigger was Newt Knight. Today, the Amos Deason house is said to be haunted. In 1951, local historian Ethel Knight, author of Echo of the Black Horn, wrote that on each anniversary of McLemore’s murder, at 11:00 p.m., “the door to the doorway in which Newt Knight stood swings open and promptly closes, as if by an unseen hand.”

Knight Company

Newton Knight quickly organized a company of approximately 125 men from Jones, Jasper, Covington, and Smith counties to defend themselves against the Confederates. They were known as the Knight Company and Newt was elected captain. A tall, powerful man, Newt was known for his imposing presence and steel-blue eyes. He was an expert with his double-barreled, muzzle-loading shotgun, and he proved to be a very skilled and resourceful guerrilla war captain. To avoid capture, the Knight men would disappear into swamp hideouts such as “Devil’s Den” or “Panther Creek.” They communicated with each other by blowing signals into hollow cattle horns. The Knight Company was aided by sympathetic local people, White and Black. In particular, a enslaved woman named Rachel helped supply Newt with food and information.

By early 1864, news of Newt Knight’s exploits had reached the highest levels of the Confederate government. Confederate Captain Wirt Thomson reported to Secretary of War James Seddon that the United States flag had been raised over the courthouse in Ellisville. Captain William H. Hardy of Raleigh, who later founded Hattiesburg, Mississippi, pleaded with Governor Charles Clark to act against the hundreds of men who had “confederated” in Jones County. Lieutenant General Leonidas Polk informed President Jefferson Davis that Jones County was in “open rebellion” and the combatants were “… proclaiming themselves ‘Southern Yankees,’ and resolved to resist by force of arms all efforts to capture them.”

The Natchez Courier reported in its July 12, 1864, edition that Jones County had seceded from the Confederacy. A few days after his destructive Meridian campaign in February 1864, Union General Sherman wrote that he had received “a declaration of independence” from a group of local citizens who opposed the Confederacy. Much has been written about whether the “Free State of Jones” actually seceded or not. Although no official secession document survives, for a time in the spring of 1864, the Confederate government in Jones County was effectively overthrown.

Confederate officials, embarrassed by the defiance of the Knight Company, determined to stamp out the rebellion once and for all. For this task they called on one of their bravest commanders, Colonel Robert Lowry of Smith County. Lowry brought his battle-hardened troops into Jones County in April 1864, and unleashed packs of howling bloodhounds to flush the Knight men out of the swamps. Colonel Lowry’s tactics were brutal but effective. Several of Newt’s men were mauled by the bloodhounds and ten were hanged. Lowry left some of the hanged men dangling from the trees as a warning to others. In the end, Lowry’s raid put the Knight Company on the run and many deserters were returned to their Confederate units. They never caught Newt Knight, however, and soon after Lowry left the area, the Knight Company re-emerged from the swamps. Lowry would later serve two terms as Mississippi governor.

By April 1865, the Confederate rebellion had been crushed and the American Civil War was finally over. Mississippi was occupied by Federal troops sent to maintain order and to protect the civil rights of formerly enslaved peoples. Captain Newt Knight was called into service by the United States Army as a commissioner in charge of distributing thousands of pounds of food to the poor and starving people in the Jones County area. Newt was also sent to rescue several Black children who were still being held in slavery in Smith County.

From 1867-1876, Mississippi was under Radical Reconstruction to protect the civil rights of Black citizens. More than 200 African Americans were elected to local, state, and federal offices in Mississippi as members of the Republican Party. However, political equality would soon be challenged by the Democratic Party and by terrorist groups such as the Ku Klux Klan. At great personal danger, Newt Knight became a strong supporter of the Republican Party. In 1872, he was appointed as a deputy U. S. Marshal for the Southern District to help maintain the fragile democracy.

In the statewide elections of 1875, however, violence and election fraud kept most African Americans and Republicans from voting. Democratic candidates committed to “white rule” were swept into office. White terrorists shot out the windows of the Governor’s Mansion to intimidate Republican Governor Adelbert Ames. Ames pleaded for federal troops to help keep order, but President Ulysses S. Grant refused. Governor Ames tried organizing a state militia to protect the voting process. In 1875, he appointed Newt Knight as Colonel of the First Regiment Infantry of Jasper County. But the tide had already turned against Republican rule in Mississippi, and Governor Ames was forced to resign. He lamented that African Americans “are to be returned to a condition of serfdom — an era of second slavery.” African Americans could not vote freely in Mississippi again for nearly 100 years.

Newt retreated to his farm in Jasper County after 1875 and brought his wartime ally, the formerly enslaved Rachel, with him. His White wife, Serena, soon left and Newt and Rachel were married. She bore him several children. Newt faced danger for living openly with a Black woman. But, as he liked to say, “There’s [sic] a lots of ways I’d ruther [sic] die than be scared to death.”

Newton Knight died February 16, 1922, of natural causes at age 85. Under the Mississippi Constitution of 1890, it was a crime for White people and African Americans to be buried in the same cemetery. Yet even in death, Newt Knight was defiant. He left careful instructions for his funeral and was buried on a high ridge overlooking his old farmstead in a simple pine box beside Rachel, who had died in 1889. The inscription on his tombstone reads, “He Lived for Others.”

James R. Kelly Jr. is a former vice president for instruction and history instructor at Jones County Junior College in Ellisville, Mississippi. He now works as a consultant and writer who splits his time between New Orleans and Mississippi.

Lesson Plan

-

Newton Knight. Date of photograph unknown. Photograph from the Herman Welborn Collection, courtesy Martha Doris Welborn. -

In 1863, Union General U.S. Grant's transports run the batteries at Vicksburg. Confederate gun crew in foreground. After the fall of Vicksburg in July 1863, many Confederate soldiers deserted and returned to Jones County. Courtesy Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, LC-USZ62-90008.

-

The Amos Deason house in Ellisville, Mississippi. Confederate Major Amos McLemore was shot and killed in the Deason home in 1863. Most people believed the man who pulled the trigger was Newt Knight. The house is said to be haunted. 2009 photograph by James R. Kelly Jr. -

Rachel Knight. Date of photograph unknown. Photograph from the Herman Welborn Collection, courtesy Martha Doris Welborn. -

The elderly Newton Knight with his grandson, Howard Knight. Date of photograph unknown. Photograph from the Herman Welborn Collection, courtesy Martha Doris Welborn.

References:

Bynum, Victoria E. The Free State of Jones: Mississippi’s Longest Civil War. Chapel Hill and London: The University of North Carolina Press, 2001.

Jenkins, Sally and John Stauffer. The State of Jones. New York: Doubleday, June, 2009.

Knight, Ethel. The Echo of the Black Horn: An Authentic Tale of “The Governor” of the “Free State of Jones.” N.p. 1951.