Major General Fox Conner, inducted into the Mississippi Hall of Fame in 1987, never achieved fame outside his chosen profession. He lived quietly and unobtrusively, he never sought publicity, and he died in relative obscurity. Yet in the minds of his fellow soldiers and in the judgment of military historians, Fox Conner was perhaps the most influential officer in the United States Army between World War I and World War II. He was General John J. Pershing’s right-hand man in building the American Expeditionary Force (AEF) in World War I. Conner was also a military historian and thinker of great reputation inside the Army. Significantly, he numbered among his protégés two of the greatest American leaders in World War II: George C. Marshall, Army Chief of Staff, and Dwight D. Eisenhower, Supreme Commander of American and British forces in the European Theater of Operations.

Fox Conner was born in Calhoun County, Mississippi, at Slate Springs on November 2, 1874, to Robert H. and Nannie Fox Conner. He was educated in the schools of Calhoun County and at age nineteen, through the sponsorship of his uncle, Fuller Fox, and Senator Hernando De Soto Money, received an appointment to the United States Military Academy at West Point. When Conner took the cadet oath on June 15, 1894, the tactical officer at West Point was John J. Pershing. Conner had begun a military career of forty-four years that took him from second lieutenant to major general, then the highest permanent rank in the U. S. Army.

Assignment in France

In 1911, Conner received a fateful assignment to the 22nd Field Artillery, French Army. After brushing up his West Point French with a dash of Berlitz, he happily took off with his wife and three small children for Versailles, where he spent a year getting acquainted with French guns and gunners. Conner’s knowledge of the French language and the French Army proved great assets after the United States entered World War I. After his stint in France, Conner commanded batteries in the West and on the Mexican border, and was on staff duty in Washington when the United States entered World War I in April 1917.

When a French mission visited Washington to see what the new ally could do for them, Conner’s experience in France made him a natural choice for liaison officer to the visitors. Shortly after, General Pershing recruited Conner to the small staff he was assembling to take to France to prepare the way of the AEF. Aboard ship, Lieutenant Colonel Conner helped draw up the artillery needs for a force then anticipated at 500,000 men. Once in France, Conner assisted the planning for the organization of the standard U. S. infantry division which, at 28,000 men, was twice the size of the British and French divisions. Indeed, it was Fox Conner, who, as operations chief for Pershing on the Western Front, oversaw the astonishing creation from scratch of America’s First World War Army and its ultimate commitment to the decisive battles of 1918. Some have called him “the father of the AEF,” but even if parenthood really belonged to General Pershing, Conner was at least the midwife.

On the Western Front

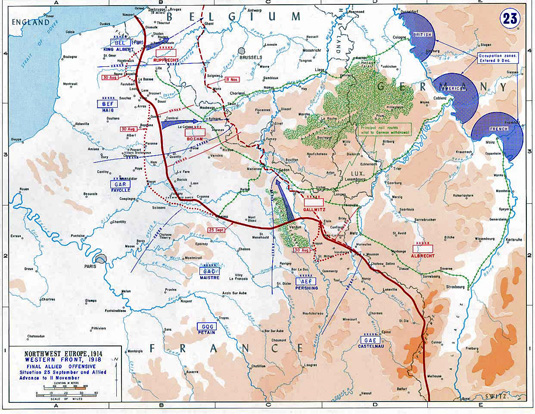

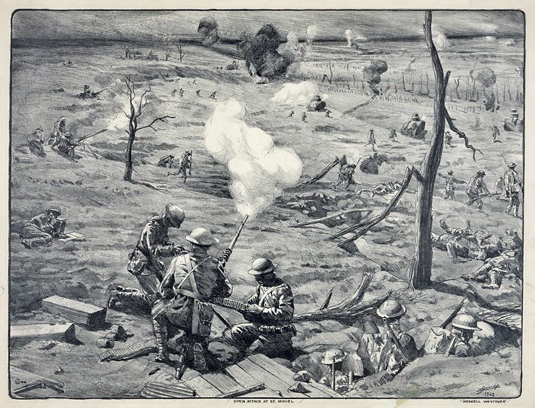

In November 1917, newly promoted Colonel Conner became the chief of operations, just as the first of his planned divisions, the First Infantry Division, went into a “quiet sector” of the front to continue its training under a French corps in the line. Lieutenant Colonel George C. Marshall led operations of the First Infantry Division and would later become Conner’s assistant at AEF Headquarters. The following year, when the First U. S. Army began its major offensive in September 1918, Pershing, with the divisions Conner had designed, attacked at the St. Mihiel salient, which Conner had identified as the Germans’ weak point. By now a brigadier general, Conner could look with considerable pride on the order-of-battle map that hung in his office in the AEF Headquarters at Chaumont showing the disposition of every division of the Western Front at the moment of the Armistice; twenty-nine of them were “his” divisions. The map today hangs in the military museum of the Smithsonian Institution in Washington.

Later, in October 1918, Conner accompanied Pershing to Allied Supreme Commander Ferdinand Foch’s headquarters to discuss recommendations to their respective governments on the enemy’s request for an armistice. Pershing and Conner warned the War Council that: “By agreeing to an armistice under the present favorable military situation of the allies and accepting the principle of a negotiated peace rather than a dictated peace, the allies would jeopardize the moral position they now hold and possibly lose the chance actually to secure world peace on terms that would insure its permanence.” They went on: “Complete victory can only be obtained by continuing the war until we force unconditional surrender from Germany.” But Pershing and Conner did not carry the point. German forces were permitted to return home with flags flying, and the legend inside Germany that they were never beaten was born. Conner quickly became convinced that the “politicians” had thrown away the victory and that some day the whole job would have to be done again.

The AEF’s wartime difficulties in dealing with fellow allies convinced Conner of the necessity for a supreme allied commander. Belatedly, French General Foch assumed the role, but Conner found his efforts to establish unity unsatisfactory. After the war, Conner lectured at the War College and put together a long, searching, acid analysis, circulated only within the Army, of the tribulations and machinations of the Allies in groping for unity before 1918. “Dealing with the enemy is a simple and straightforward matter when contrasted with securing close cooperation with an ally,” he wrote. He went on to insist that: “America should, if she ever indulges in the doubtful luxury of entering another coalition, advocate the establishment of a Supreme War Council, coincident with entering a war with allies….”

Conner and Marshall had come home on the Leviathan with Pershing after the war for the triumphal welcome in New York. During one break in their busy rounds in the fall of 1919, the three headed off for a ten-day respite of hunting at the vast Adirondack camp that belonged to the family of Conner’s wife, Virginia Brandreth. Conner took a Sunday off to visit his friend George Patton at Camp Meade. There, Patton made a point of introducing Conner to Dwight Eisenhower, whom Conner thought worth keeping an eye on.

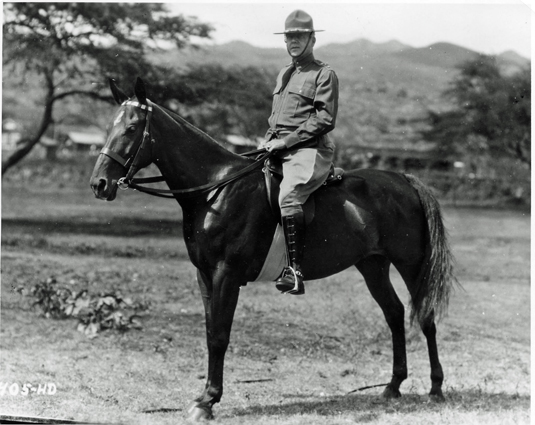

Panama Canal

In 1922, when Conner was ordered to Panama to command the 20th Infantry Brigade in defense of the Canal Zone, he asked Eisenhower go along as his executive officer. Eisenhower, who had also been impressed by Connor, recalled, “Of course, I agreed.” There, Conner mentored his junior officer on leadership, military history and the lessons of the Great War. “In sheer ability and character, he was the outstanding soldier of my time,” Eisenhower said. “Outside of my parents he had more influence on me and my outlook than any other individual, especially in regard to the military profession.” Eisenhower fondly recalled Conner as being a man of “great probity, great honesty—a born leader of men. He had a mind like a steel trap. But he was never the hard or high-pressure type. He gave the appearance of being leisurely. He was sort of drawly. …came from Mississippi, you know….”

Conner groomed his young charge for a future high leadership position in the Army. Conner was convinced that the flawed Treaty of Versailles contained the seeds of another major war and he believed that a man of Eisenhower’s talent would play a vital role in the coming conflict. Under Conner’s guidance, Eisenhower undertook the serious study of military history for the first time, grappling with problems faced by the great commanders of the past. Conner also drew on his personal experiences in France. “We’d go over the First World War and ‘war game’ the battles ourselves — see where mistakes had been made,” Eisenhower remembered.

Most importantly, Conner frequently returned to the theme that the next war would be a coalition war, and that unity of command would be essential.

Eisenhower recollected: “We went back over the history of the attempts to unify the forces in World War I, and he constantly insisted that the methods of coordination under [Supreme Allied Commander] Foch were not sufficient.

“There had to be a definite command situation, he used to say. It would have to be worked out so the commander and command decisions would be respected by everyone. He laid great stress in his instruction to me on what he called ‘the art of persuasion.’ Since no foreigner could be given outright administrative command of troops of another nation … they would have to be coordinated very closely and this needed persuasion. He would even talk about the types of organization he thought would bring this about with the least friction. He would … get out a book of applied psychology and we would talk it over…. How do you get allies of different nations to march and think as a nation? There is no question of his molding my thinking on this from the time I was thirty-one…. I would not say that his views had any specific influence on my conduct of SHAEF, [Eisenhower’s World War II Supreme Headquarters, Allied Expeditionary Force] but his forcing me to think about these things gave me a preparation that was unusual in the Army at that time.”

Looking back on his Panama sojourn with Conner, Eisenhower considered it, “one of the most satisfying experiences of my life.”

Deputy chief of staff

After Panama, Conner served two years in Washington, D.C., as army assistant chief of staff for supply and then as deputy chief of staff, the second highest position in the Army. He did his job of maintaining the Army’s military effectiveness within the confines of a small peacetime budget so well that senators and congressmen began to refer to him as the “Hoover of the War Department.” Conner, however, did not enjoy either the Washington atmosphere or the sort of desk-bound administration his job entailed and he was glad to take command in Hawaii in 1928. A few years later, while Major General Conner was commanding the First Corps Area with headquarters in Boston, President Franklin D. Roosevelt considered inviting Conner to replace the outgoing Douglas MacArthur as Army Chief of Staff. “Now, General Conner,” said Roosevelt, “we’ve heard reports that you do not want to come to Washington … and I want to know if that’s so.” “That’s right, Mr. President,” Conner replied. “I wouldn’t go to Washington again. …I’d resign first.” Conner had no desire for more staff work in Washington.

Instead, General Conner threw himself enthusiastically into the principal task of a corps-area commander of those days. Running the Civilian Conservation Corps camps throughout New England in the 1930s was not a political job, but a military one — not since the war had Army officers had so many men in their charge — and Conner toured the camps constantly, checking the work, tasting the food, and instructing the junior officers. Conner stayed in Boston until his retirement in 1938.

Eisenhower visited his mentor several times when he was in Boston. “Whenever we got together, we went back to those same old subjects. Hitler had come [into power]. Now it was getting closer; he was getting more definite in his conviction of what would happen. We kept in close touch right up until the war. He never lost his bounce….”

In the fall of 1941, after his retirement, Conner was hunting at Brandreth Lake when he was invited to Pine Camp to observe some armored maneuvers, an apparently dashing but somewhat ineffectual exercise. He made a comment that became a classic critique: “Too much blitz, too little krieg.” Soon after, he was injured while trying to get a truck out of the mud at the Brandreth estate. He was also badly shaken when someone told him the Japanese had bombed Pearl Harbor. “Get me back to Washington as soon as you can,” he said. “The old man [Pershing] will need me.”

Pershing was, by then, a permanent resident at Walter Reed Hospital. Conner was taken there too. He recovered from the accident and spent some of his days there as an unofficial liaison officer between Pershing’s apartment and the Army and Navy Club, where he delivered some old soldiers’ views on how the current war [World War II] should be won. Conner later returned to the Brandreth estate where he spent his remaining days until his death in 1951.

Although there is no evidence Conner corresponded directly with Eisenhower during the war, if General Conner didn’t tell General Eisenhower how to win World War II, he had already done what he could twenty years before to get him ready.

This is a condensed and edited version of an article that was originally published in the August 1987 edition of The Journal of Mississippi History. Charles H. Brown, an editor for the New York Times Magazine, interviewed General Eisenhower in 1964 and drafted an article on Fox Conner, which was never polished or published, and after Brown’s death, it rested on the shelves of the Eisenhower Library in Abilene, Kansas. Brown’s article was edited in 1987 by John Ray Skates who at that time was a visiting research professor at the Department of the Army Center of Military History in Washington, D.C., and on leave from his position as professor of history at the University of Southern Mississippi. This version of the article was condensed and edited by Peggy Jeanes, editor, Mississippi History Now.

-

Major General Fox Conner was inducted into the Mississippi Hall of Fame in 1987. Portrait by Eric McDonald. Courtesy Collection of the Museum of Mississippi History, Mississippi Department of Archives and History. -

Western Front, World War I. The St. Mihiel salient was a 200-square-mile triangle jutting 14 miles into the Allied lines between the Moselle and Meuse rivers. Courtesy Perry-Castaneda Library Map Collection, University of Texas Libraries, The University of Texas at Austin.

-

Open attack at St. Mihiel. When the First U. S. Army began its attack here, it was just 16 months since Conner had persuaded Pershing that this was where the Americans should make their big push. Courtesy Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, LC-DIG-pga-03886. -

General Fox Conner at the Panama Canal Zone as commander of the 20th Infantry Brigade, circa 1922. Serving as his executive officer was Dwight D. Eisenhower. Courtesy The Eisenhower Presidential Library and Museum. -

Camp Gaillard, Panama Canal Zone, circa 1922. Courtesy The Eisenhower Presidential Library and Museum. -

Conner, deputy chief of staff in Washington, D.C., March 8, 1926. Courtesy Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, LC-F81-39386. -

Major General Fox Conner. Courtesy United States Army.