In 1949, the City of Clinton received one of the first sixty state historical markers. Unfortunately, the tablet portion of the marker has been missing for several decades. Although an updated replacement marker was erected in 2015, the whereabouts of the original remain a mystery. What makes the story of this missing marker all the more intriguing is that it referenced a violent and controversial episode in the city’s past. While this incident became more commonly known as the “Clinton Riot,” newspaper reporters and other eyewitnesses often referred to it as the “Clinton Massacre,” which is the title of a Mississippi Freedom Trail marker erected in 2021. The purpose of this article is to bring greater awareness to this little known, but terribly important event in Mississippi history.

The Republican rally

Black males in Mississippi, most of whom had joined President Abraham Lincoln’s Republican Party, first began voting in 1867 by electing candidates to the Constitutional Convention of 1868. By 1875, African American males had experienced eight years of suffrage, and September 4 of that year held the promise of continuing the incorporation of freedmen within the state’s political process. Republicans planned political rallies that day at Utica and Clinton in Hinds County and at Vernon in nearby Madison County. Whole families of Black Republicans gathered at Moss Hill, the site of a former plantation in Clinton destroyed by Union troops during the Vicksburg Campaign of 1863. Estimates of the attendance that day ranged from 1,500 to 2,500, nearly all consisting of freedmen and their families who gathered to enjoy an afternoon of picnicking and politics. There were also about seventy-five White people present, eighteen of whom were known to be Democrats from nearby Raymond.

Governor Aldelbert Ames was initially scheduled to speak to the crowd, but he asked Captain H.T. Fisher, a former Union officer and editor of a local Republican newspaper, to speak in his stead. Aware of racial tensions, Hinds County Republican leaders issued an invitation to the local Democratic Party to send a speaker of their own in the spirit of open debate. The Democratic candidate for state senate, Amos R. Johnston, addressed the crowd for the first hour of the rally without incident. However, when Fisher took the platform next, he was heckled by the group from Raymond. Several witnesses, including a Black Republican named Daniel C. Crawford, reported hearing one of the Raymond men shout, “Well, we would have peace if you would stop telling your damned lies.”

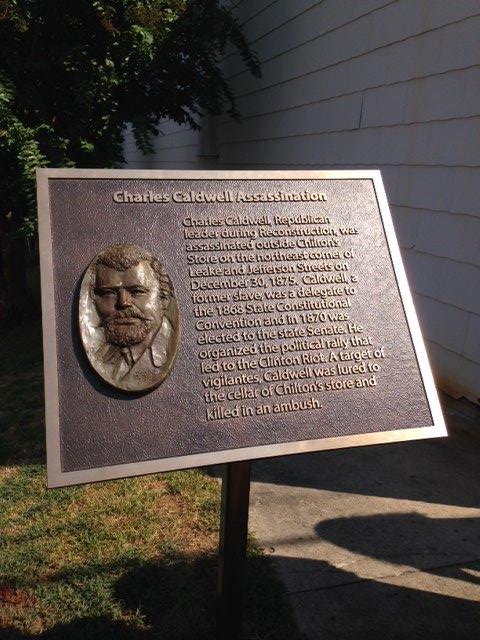

Republican organizers, including Black state senator Charles Caldwell from Clinton, made several appeals for peace. Yet, the events of that afternoon quickly escalated into violence. Eugene Welborne, another rally organizer, testified that many of the White Democrats in attendance fell into formation, brandished weapons, and trained them upon the crowd. “The thing opened just like lightning,” he recalled, “and the shot rained in there just like rain from heaven.” Frantic African American mothers scooped up their terrified children and fled to the woods in every direction to avoid the gunfire. One African American mother hid her infant child in the hollow of a nearby tree for protection. Fatalities that day numbered three White men and at least five Black people, two of whom were children.

Sadly, the violence on September 4 merely served as a prelude to the racial atrocities committed during the days and weeks that followed. Amidst rumors of an African American plot to storm the town, Clinton’s mayor called for assistance from nearby White Liners (essentially a paramilitary unit of the Mississippi Democratic Party) in neighboring towns, including Vicksburg and Raymond. These White Liners traveled by railroad to Clinton, and their numbers quickly swelled to several hundred before nightfall. “They [the White Liners],” Welborne grimly recalled, “just hunted the whole country clean out, just every [black] man they could see they were shooting at him just the same as birds.”

Sarah Dickey, a White educator from Ohio who had moved to Mississippi to educate African American women and children, described the scene in a letter to President Ulysses S. Grant. She declared, “I was at the republican mass meeting, held at this place [Clinton] … the democrats, who were on the ground, went there for the express purpose of creating a disturbance and of killing as many as they could … You hear a great deal about the massacre at Clinton, but you do not hear the worst. It cannot be told.” While the violence following September 4 resulted in no additional deaths of white Democrats, the African American death toll could only be estimated at between thirty and fifty. The events of the days following September 4 turned a presumed race riot into a massacre.

The Boutwell Report

In order to influence the upcoming statewide elections to be held on November 2, 1875, and to place their stamp on the historical narrative, Democratic Party leaders dramatized the events in Clinton as a “Premeditated Massacre of the Whites” by hundreds of heavily armed and organized African Americans. These Democratic accounts were subsequently refuted by a 1876 report prepared by a special United States Senate investigative committee chaired by Senator George S. Boutwell of Massachusetts (the “Boutwell Report”). After acquiring hundreds of sworn testimonies, the Boutwell Report concluded that “the riots … at Clinton on the 4th of September, were the results of a special purpose on the part of the democrats to break up the meetings of republicans … and to inaugurate an era of terror, not only in those communities, but throughout the state.” The most damning evidence cited in the Boutwell Report was an article published by Raymond editor George W. Harper in The Hinds County Gazette just a few weeks prior to the rally at Clinton, which urged:

There are those who think that the leaders of the radical party [the Republican Party] have carried this system of fraud and falsehood just far enough in Hinds County, and that the time has come when it should be stopped – peacefully if possible, forcibly if necessary … whenever the radical speakers proceed to mislead the negroes, and open with falsehoods, and deceptions, and misrepresentations, that the committee stop them right then and there and compel them to tell the truth.

On the morning of the rally, Republican leaders suspected that the group from Raymond came to Clinton in order to serve as such a “committee.” Later, the Boutwell Report declared the connection to be true.

Clinton served as the inauguration of the infamous Mississippi Plan, a plan devised by the Mississippi Democratic Party to regain political control of the state by any means necessary. Despite countless requests for federal assistance by Governor Ames and citizens like Sarah Dickey, President Grant declared that “the whole public are tired out with these annual, autumnal outbreaks in the South,” and he adopted a policy of non-intervention with respect to Clinton and the rest of the former Confederacy.

“The worst. It cannot be told.”

While local historiography has placed the responsibility for the countless murders which took place after September 4 on White Liners from outside of Clinton, testimony from the Boutwell Report reveals that Clintonians accompanied White Liners and helped to identify targeted victims. In several instances, those victims recognized their neighbors and friends among the assailants.

William P. Haffa, a White school teacher who had moved to Mississippi from Pennsylvania, served as a Republican justice of the peace and was up for re-election in 1875. His wife, Alzina, recalled the morning of September 6 when fifty to seventy-five men broke into her home and murdered her husband. Alzina identified two of her family’s attackers, Sid Whitehead and another man named Mosely. Mosely choked her after she called him by name, and Whitehead refused medical assistance for her husband after he had been shot. The rest of her testimony follows:

I had a nursing-baby then, and it was lying on the bed, screaming … they broke a shutter off the window and fired at Mr. Haffa … They fired twice, and I went to him … and says he to me, “Mamma, I want water.” As soon as I could get a light I gave him water and laid him down, and ran out for assistance, and sent my little boy over to some colored people, and they came rushing over … He said, “Mamma, I am going to die,” and he asked God to have mercy on his soul, and he laid his head on my shoulder and expired.

On September 5, White Liners dragged Square Hodge, an African American man, from his home as his distraught wife and children watched. As these men invaded their home, Hodge family members scrambled into hiding. Hodge’s wife, Ann, testified that “they made him [Hodge] come out from under the bed, and started to shoot under the house – mother put the children under the house.” She then recalled that these men demanded to know if her husband had attended the Clinton rally the previous day. Ann identified one of her neighbors, Mr. Quick, among the mob. Although Quick did not appear to display any sympathy at the time of her husband’s kidnapping, he returned to the Hodge home a week later to help Ann find and recover her husband’s body. Sadly, the only way that she could identify his corpse was from the way she had tied his shoes the night he had been kidnapped.

As chairman of the Hinds County Republican Party, William Clark also attended the political rally in Clinton. After the war, Clark, an African American, helped to organize and pastor Pleasant Green Baptist Church in Clinton, but he was also interested in politics. A few days after September 4, Jesse Furver, a lifelong friend of Clark and a White minister, approached him. Furver informed Clark that he intended to kill him because of his participation in the Republican Party and the rally. Clark remained calm and tried to talk Furver out of the deed by recounting Bible stories of friendship. Finally, Furver agreed to let Clark live by firing the gun above Clark’s head. This allowed Clark to drop to the ground, thereby making it look as though Furver had carried out the heinous deed. In order to protect Furver, Clark promised that he would never be seen in Hinds County again. It was a promise that he kept.

The silence broken in Clinton

Understanding the complicated period of Reconstruction is difficult, especially in the South where the mere mention of the word “Reconstruction” conjures extreme emotions and opinions. Historian Eric Foner acknowledges the same. “Sadly,” he laments, “it will take a long time for scholarly writing to overcome the distorted image of Reconstruction that so powerfully penetrated the national consciousness.” Foner, however, remains optimistic and points to a small, but growing trend on the part of historians to attempt to unite the historical memory of Reconstruction with efforts of racial reconciliation.

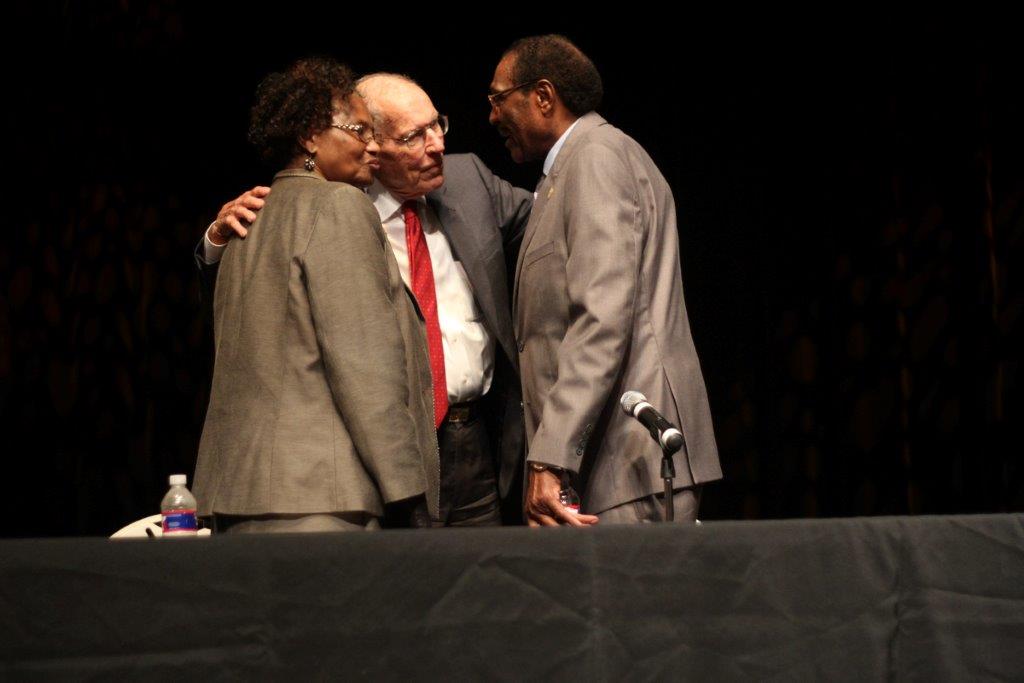

On September 4, 2015 (the 140th anniversary of the Clinton Riot), the city of Clinton became part of this small, but growing, trend referenced. The city hosted a symposium to educate the community about the history of the Clinton Riot and unveiled two new historical markers related to this event. Among those who comprised the symposium panel was Robert Clark, the first African American elected to the Mississippi House of Representatives since Reconstruction. He was not, however, the first member of his family to be involved in politics. That honor is held by his aforementioned grandfather, William.

Melissa Janczewski Jones is a visiting instructor of history at Mississippi College. She also served as editor of Mississippi History NOW from 2013 to 2018. This article was updated in 2021.

Click here to access “Voices of the Clinton Riot,” a dramatic reading performed in Clinton on September 4, 2015, during a ceremony commemorating the 140th anniversary of the Clinton Riot and dedicating two new historical markers related to this event.

Other Mississippi History NOW articles:

Reconstruction in Mississippi, 1865-1876

Isaiah T. Montgomery, 1847-1924 (Part I)

Isaiah T. Montgomery, 1847-1924 (Part II)

About the Mississippi Constitution of 1890

Lesson Plan

-

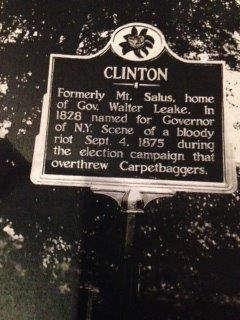

Photograph of the original 1949 Clinton historical marker referencing the Clinton Riot. Courtesy of the Mississippi Department of Archives and History. -

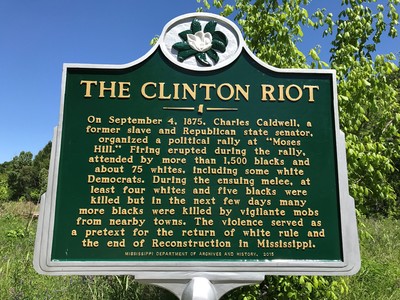

Photograph of the first historical marker about the Clinton Riot erected in 2015.

-

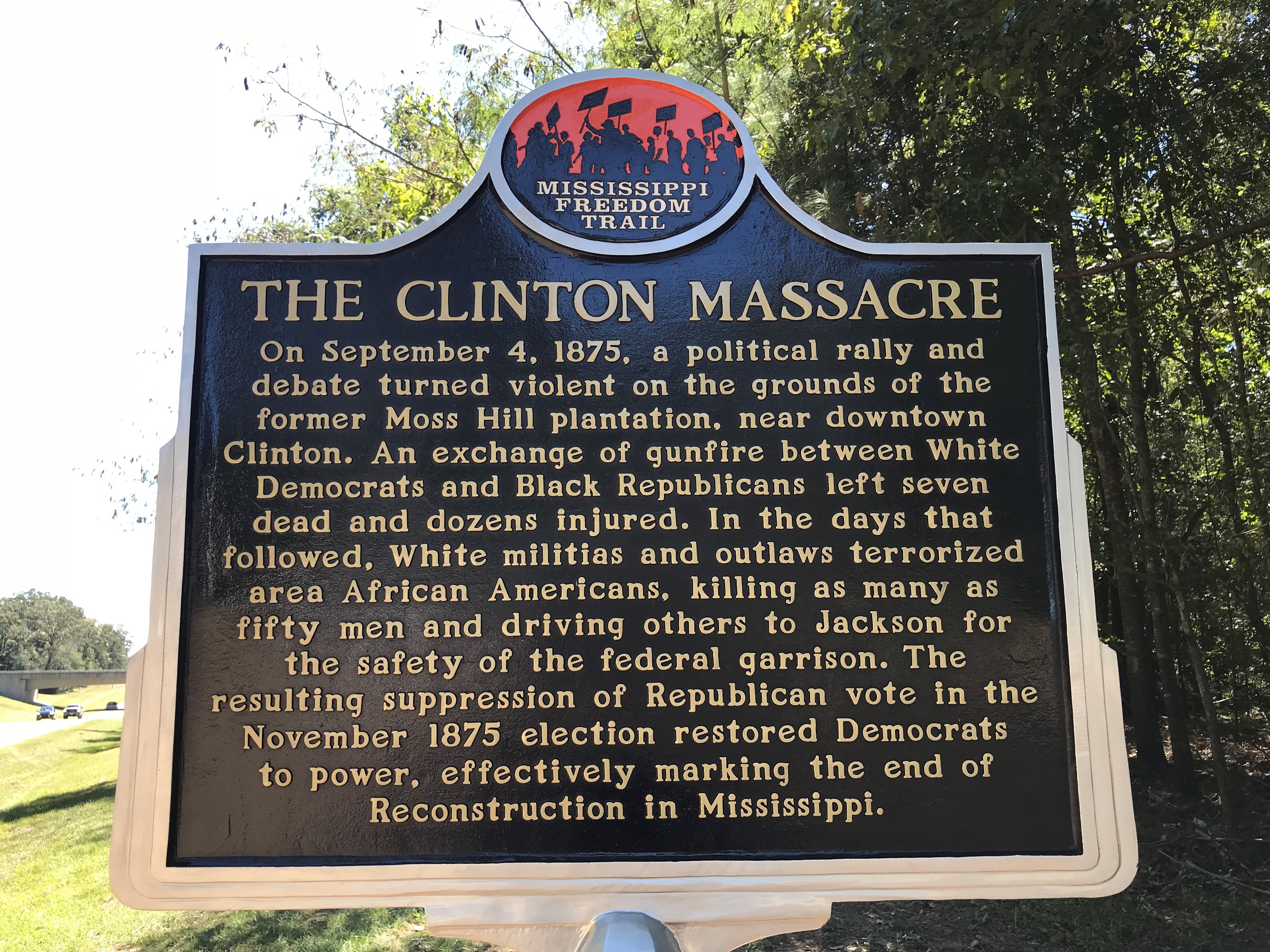

Photograph of the Mississippi Freedom Trail marker dedicated on September 23, 2021. -

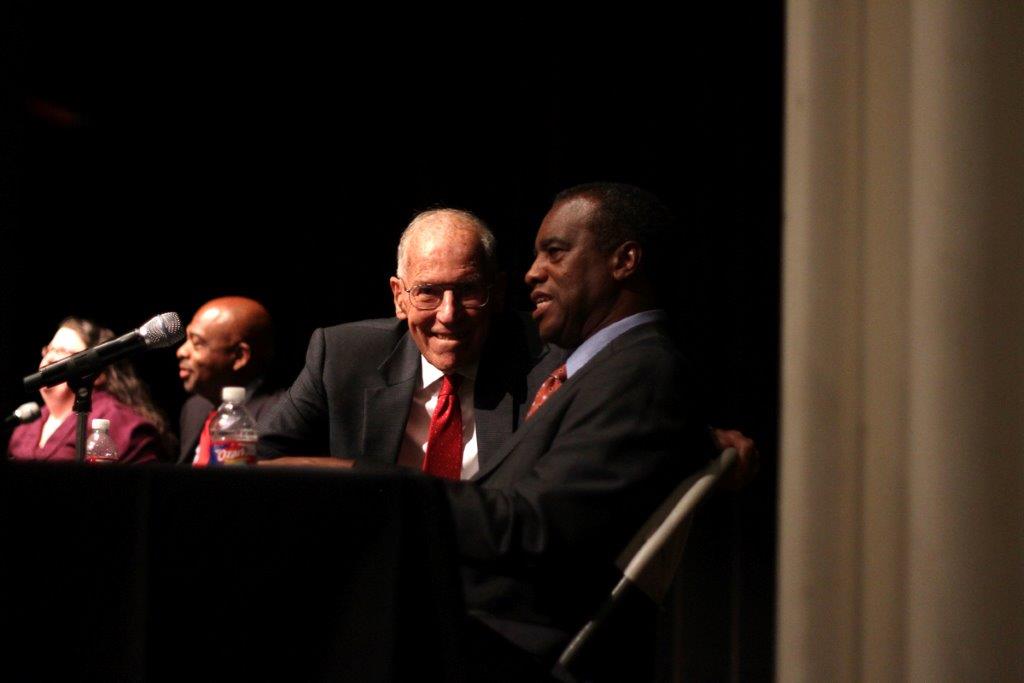

Photograph of Governor William F. Winter with Robert G. Clark, Jr. and his wife, JoAnn, at the symposium on the Clinton Riot and racial reconciliation held by the City of Clinton. Courtesy of James Matthews. -

Photograph of Robert G. Clark, Jr. and his wife, JoAnn, greeting guests at the symposium on the Clinton Riot and racial reconciliation held by the City of Clinton. Courtesy of James Matthews. -

Photograph of panelists at the symposium on the Clinton Riot and racial reconciliation held by the City of Clinton. Panelists from left to right: Dr. Susan Glisson, Executive Director of the William Winter Institute for Racial Reconciliation, Justice James Graves, Governor William F. Winter, and Ottawa Carter. Not shown: Rev. Neddie Winters, President of Mission Mississippi. Courtesy of James Matthews. -

Photograph of the new historical marker for state senator Charles Caldwell, the last known victim of the Clinton Riot killed on December 30, 1875.

Sources and suggested readings:

Boutwell Report. 44th Cong., 1st Sess., Mississippi in 1875, Vols. I and II.

Campbell, Will D. Robert G. Clark’s Journey to the House: A Black Politician’s Story. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2003.

Foner, Eric. Forever Free: The Story of Emancipation and Reconstruction. New York: Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, 2005.

Foner, Eric. Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution, 1863-1877. New York: Harper & Row, 1988.

Harris, William C. The Day of the Carpetbagger: Republican Reconstruction in Mississippi. Baton Rouge: Louisiana University Press, 1979.

Howell, Walter. Town and Gown: The Saga of Clinton and Mississippi College. Saline, Michigan: McNaughton & Gunn, 2014.

Oshinsky, David M. “Worse Than Slavery”: Parchman Farm and the Ordeal of Jim Crow Justice. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1996.