If asked to name the most famous, the most successful baseball pitchers in history, most sports enthusiasts would name Christy Mathewson, Walter Johnson, Cy Young, Bob Feller, Whitey Ford, Sandy Koufax, Bob Gibson, Roger Clemens . . .

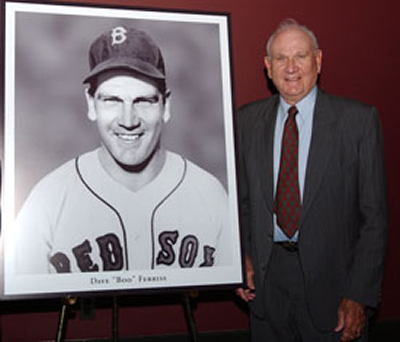

But know this: For two and a half seasons, before a freak shoulder injury sidetracked him, Mississippian David “Boo” Ferriss was as promising, as effective a pitcher, as any of those baseball legends. Pitching for the Boston Red Sox in the 1945, 1946, and halfway into the 1947 seasons, Ferriss was the toast of Boston and the most dominant pitcher in the American League.

As a rookie in 1945, Ferriss won twenty-one games for an otherwise forgettable Red Sox team that finished in seventh place in an eight-team league. He won his first eight major-league starts, and beat every other American League club in the process. And it gets better. He pitched twenty-two scoreless innings to begin his career.

1946 was a very good year

In 1946, he won thirteen straight games at Fenway Park. That is still a major-league record. That same season, Ferriss won twenty-five games and lost only six, pitching twenty-six complete games and six shutouts. He pitched still another shutout in the 1946 World Series.

At age 25, ruggedly handsome Dave “Boo” Ferriss was a strapping, raw-boned powerhouse, standing 6 feet 2 inches and weighing 208 pounds. He was broad of shoulder and slim of waist. Ballplayers did not lift weights then, but Ferriss was what baseball people call “country strong.” Ferriss was living a life-long dream to pitch in the big leagues. He was at the top of his game in an era when baseball was America’s sport.

Then on a chilly, damp night in Cleveland, Ohio – July 14, 1947 – the world changed for Ferriss. Boston and Cleveland were scoreless with the hometown Indians batting in the bottom of the seventh inning. The bases were loaded with two outs. Ferriss was on the pitcher’s mound. He was that rare pitcher with such command of all his pitches, he would throw any pitch at any time and throw it for a strike. George Metkovich, Cleveland’s lead-off hitter, was at the plate and the count was full at three balls and two strikes. Metkovich was probably looking for Ferriss to throw a fast ball. Ferriss figured Metkovich was thinking that and threw an overhand curve. Metkovich struck out.

As he delivered the pitch, Ferriss felt something snap in his shoulder. He had no idea what had happened. He just knew that pain shot through his arm and then it went numb. His arm would never be the same. One of the most promising careers in baseball history was essentially over just as it was getting started.

Baseball is Delta pastime

Ferriss was born in Shaw, Mississippi, at the beginning of the Roaring Twenties. The story of how “Boo” Ferriss got his nickname is typical of how nicknames are created across the South: When he was a toddler, he tried to get the attention of Will D., his older brother. He was trying to say, “Brother,” but it came out, “Boo.” Everyone in the family had a good laugh. And little David Meadow Ferriss, born December 5, 1921, had a new name. For the longest time, he was Little Boo. And brother Will D. – William Douglas Ferriss, Jr. – was Big Boo.

William Douglas Ferriss, Sr., Boo’s dad, was a cotton farmer. His parents had come to Mississippi from Virginia and Kentucky. They settled in Yazoo County and William Douglas – W.D. to his friends – eventually moved to Shaw. There he met his future wife, Lellie Meadow, whose family had moved from Tennessee to Shaw when she was a child.

Although W.D. Ferriss farmed for a living, he was a baseball man at heart. He played, coached, and umpired baseball, and always took Little Boo with him. Baseball truly was the Mississippi Delta’s pastime in the 1920s and 1930s. Farmers worked hard and played hard. Every town had at least one semi-pro team and competition was fierce. Huge crowds attended weekend games.

W.D. Ferriss never pushed his youngest son into the game. There was no need. Little Boo played all sports, but he loved baseball. Indeed, he could never get enough of it. He played anywhere he could find a game, and when there was no game, he played by himself, pitching to the front steps of his house.

His first organized game was one to remember. At age 13, and in the seventh grade, he was called down out of the stands to play second base for the high school team. A much larger and older opposing player bowled over him on a close play at second base, breaking his right wrist. That summer, right-handed Ferriss learned to throw the ball left-handed. His ability to throw either right- or left-handed would amaze baseball people throughout his career.

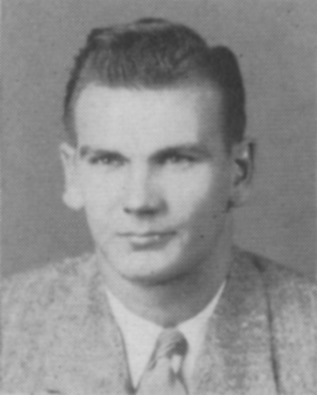

Ferriss went on to become a high school star athlete in football, basketball, baseball, and tennis at Shaw. But baseball was his passion, and major-league scouts noticed his prodigious skills early on. Several professional teams offered contracts, but Boo’s parents were adamant that he should attend college. He had scholarship offers from the University of Alabama, University of Mississippi (Ole Miss), and Mississippi State. He chose State and became the first baseball player to receive a full scholarship to what was then Mississippi State College. Ole Miss and Alabama had offered half scholarships. Dudy Noble, State’s coach and athletic director, offered to pay the full cost for Ferriss’s education, including room and board. This was 1938, and Mississippi was still in the grips of the Great Depression. Ferriss accepted Noble’s offer.

Ferriss was hugely successful at State, both on the diamond and in the classroom as an honor student. In baseball, he pitched right-handed and played first base left-handed. Once, at games in Alabama, he pitched on Friday and played first base on Saturday. That led to his having to settle two fans’ bet. On Saturday, the two Alabama fans came down from the stands and each gave Ferriss a five-dollar bill. “My friend here says you’re the guy who pitched yesterday, but I say you aren’t because the guy who pitched yesterday was right-handed. You’ve got to settle the bet,” one of them said. Ferriss responded, handing both bills to the other guy, “Sorry, fella, but that was me.”

Pitching for the Army

On December 7, 1941, Ferriss was in his junior year at State when he heard the news that the Japanese had attacked Pearl Harbor, bringing the United States into World War II. By then, Ferriss was more certain than ever that he wanted to make his living in baseball. He and his father had decided that he would play his junior season at State, and then sign a contract with a professional team. The hope was that he could sneak in a summer of professional ball before receiving a draft into military service.

And that is what happened. Ferriss signed with the Boston Red Sox which sent him to its farm team in Greensboro, North Carolina. There, at age 20, he led Greensboro of the Class B Piedmont League to the league championship.

Read excerpt of Ferriss interview where he talks about signing with the Boston Red Sox.

When he arrived home in Shaw after the season, so did his draft papers. He wound up in the U. S. Army Air Corps, stationed at Randolph Field in Texas as a physical training instructor. When he was not training soldiers, Ferriss was playing baseball for Randolph Field in a league with many professional players, including several major-leaguers. In fact, he played for former major-leaguer and University of Texas Coach Bibb Falk in a league that was probably more talented than the Piedmont League. Falk saw much promise in the easy-going young man from Mississippi.

Games were played in Texas league ballparks, often before huge crowds. In the summer of 1944, Ferriss finished the season with a 20-8 pitching record and also won the league batting title with a .417 average, nosing out St. Louis Cardinals star and future Hall of Famer Enos “Country” Slaughter, who batted .414. For Ferriss, the experience was invaluable.

Ferriss and Coach Falk were looking forward to another spring and summer of Army ball, but Ferriss suffered a recurrence of asthma, a problem that had bothered him off and on since youth. He was hospitalized for weeks at Randolph Field. In February 1945, he was given his medical discharge from the Army.

Ferriss reported for spring training with the Red Sox Class AA Louisville team in 1945, expecting to pitch at least another season of minor league ball before getting to the major leagues. Instead, he was called to the Boston Red Sox on the day he was supposed to have pitched on opening night for Louisville. Once with the Boston Red Sox, Ferriss began that remarkable stretch in which he won his first eight starts. He was in the major leagues.

Hear Ferriss talk about the call from the Boston Red Sox. Audio clip from 1979 interview courtesy of The Center for Oral History and Cultural Heritage at The University of Southern Mississippi.

Unlike most pitchers, who are usually poor hitters, Ferriss hit like a natural hitter. On days when he did not pitch, he was often called on as a pinch hitter. He would further amaze his teammates and opposition alike by pitching batting practice left-handed on his off days.

Major league career in jeopardy

Then came that fateful day in Cleveland when Ferriss felt something pop in his shoulder. Today, a pitcher would be rushed to the hospital for an MRI, a diagnostic tool that gives an image of a cross-section of an injured area. Such an injury, a torn cartilage in the shoulder, would be repaired with arthroscopic surgery and the pitcher would only miss the rest of the season.

What was Ferriss’ medical treatment in 1947? “They rubbed me down with rubbing alcohol and told me to be sure to wear a coat,” Ferriss said with a chuckle more than half a century later. “You know how they ice arms down now? Back then, they used heat.”

The next day, Ferriss could not lift his right hand above his shoulder. “The only way I could even toss the ball was underhand,” he said. Two weeks later, Ferriss was back in the Boston Red Sox pitching rotation. “Like I say, you either pitched or you went home,” Ferriss said. “I was where I always wanted to be. I wasn’t ready to go home.”

But his shoulder was never the same. Ferriss tried his best to keep pitching. He finished the 1947 season with a 12-11 record for Boston. In 1948, while pitching sparingly in Boston, he won seven games and lost only three as a spot starter. “I just didn’t have any pop on my fast ball,” he said.

His arm nearly gone, Boo Ferriss got by on grit and guile. “Some days were better than others; I could still throw O.K. at times, but it was never like it had been.” The “O.K.” days pretty much ended in 1949, when, Ferriss said, “My arm went dead, completely dead. I didn’t have anything.”

It is no great stretch to say that such catastrophic misfortune as Ferriss suffered in 1947 would have ruined lesser men. His former Red Sox teammates, guys like baseball Hall of Famer Bobby Doerr, marvel at how Ferriss dealt with his misfortune. “As great a pitcher as he was, and he was one of the best, he is an even better person,” Doerr said in 2004. “Among the people I’ve known, Boo would be the one you’d copy if you could and say I want to be like that man. I want my son to be like that man. He was that way before he got hurt and he has remained that way. You want to know about Boo Ferriss? He’s the best.”

Ferriss said, “That’s all water under the bridge. I just figure the good Lord had other plans for me.”

Coming home to coach

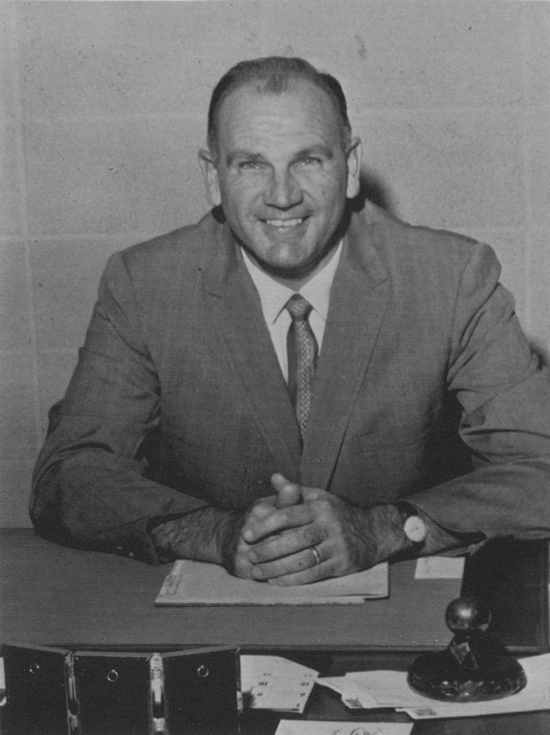

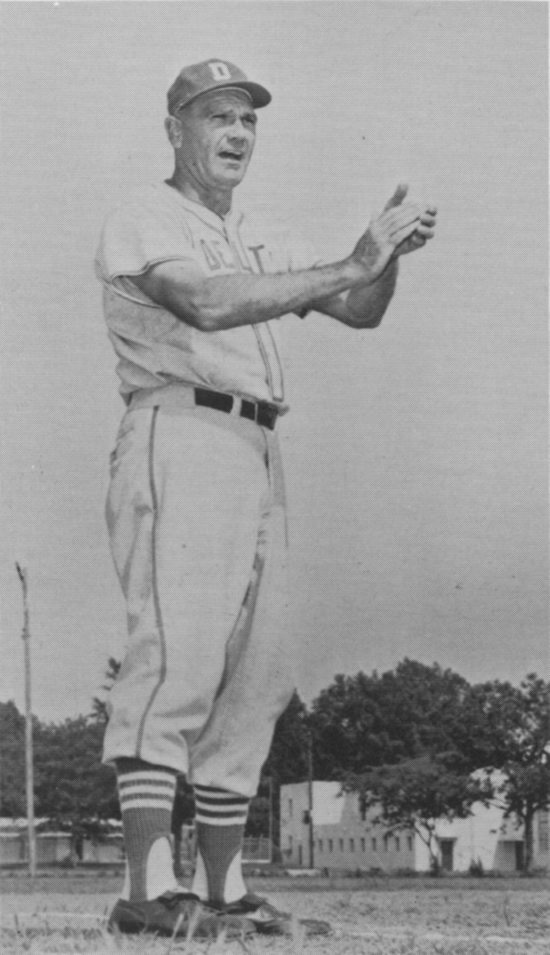

So, after pitching stints with Red Sox minor league teams in Birmingham and Louisville, Ferriss hired back on as pitching coach of the Boston Red Sox. He served in that capacity from 1955 until 1959, when he accepted a job to become the baseball coach and athletic director at Delta State in Cleveland, Mississippi. He built that college program from scratch, literally carving a baseball diamond out of a bean field.

In his twenty-six seasons at Delta State, his teams won 639 games and lost only 387 and often defeated much larger schools such as Ole Miss, Mississippi State, Alabama, Notre Dame, and Southern Mississippi. His teams won four Gulf South Conference championships, three National Collegiate Athletic Association, or NCAA, regional titles, and placed second once and third twice in the College World Series. He retired from Delta State in 1988 and became the school’s most avid fan and chief fundraiser.

Far more important to Ferriss today than the victories and championships his Delta State teams achieved, are the relationships he maintains with his former players, including current Delta State coach Mike Kinnison. Ferriss is like a second father to scores of former DSU players, who he corresponds with in elegantly handwritten letters and cards. The Mississippi baseball ranks are filled with former Delta State players who played for Ferriss.

2004 was a very good year

In May 2004, the 82-year-old Ferriss watched from the stands as Kinnison’s Delta State Statesmen finally won a national championship. After receiving the trophy, Kinnison leaped into the grandstand, bounded up the bleachers, and presented the trophy to a teary-eyed Ferriss. “He’s Delta State baseball,” Kinnison would later say of Ferriss. “He’s the guy who laid the foundation. He’s the one that built the program to what it has become and he’s still there today, doing anything and everything he can to make it better.”

Barry Lyons, who played for Ferriss from 1979 to 1982 before going on to play in the major leagues for the New York Mets, Los Angeles Dodgers, and California Angels, wept openly that championship day.

“Delta State baseball is special,” Lyons said. “We all know we are part of something very special and we all know who made it that way. I’m like everybody else. I’m happy for me, I’m happy for the program, but I’m happiest for Boo Ferriss. He, more than anyone, deserves this moment.”

In the fall of 2004, Ferriss watched as his beloved Boston Red Sox won their first World Series since 1918. “Can you believe it? Delta State won the national championship and the Red Sox won the World Series in the same year,” Boo Ferriss said. “It’s almost too good to be true.”

Note: Ferris died on November 24, 2016, about two weeks shy of his 95th birthday.

Rick Cleveland is sports columnist for The Clarion-Ledger.

Lesson Plan

-

Ferriss became the first baseball player to receive a full scholarship to Mississippi State. Photograph of Ferriss as a sophomore is from the 1941 Mississippi State yearbook, The Reveille. Courtesy Mississippi Department of Archives and History. -

As a rookie for the Boston Red Sox in 1945, Ferriss won twenty-one games. Photo courtesy Boston Red Sox.

-

Ferriss became Delta State’s athletic director and baseball coach in 1959. Photograph of Ferriss is from the 1965 Delta State yearbook, The Broom. Courtesy Mississippi Department of Archives and History. -

Delta State’s Coach Ferriss. Photograph of Ferriss is from the 1965 Delta State yearbook, The Broom. Courtesy Mississippi Department of Archives and History. -

Ferriss with a photograph from his early career prior to the November 2002 induction ceremonies for the Boston Red Sox Hall of Fame. Photo courtesy Mississippi Sports Hall of Fame and Museum.