In the 1600s, Colonial French settlers brought Christianity into the lands that are now the state of Mississippi. Throughout the period of French rule and the period of Spanish dominion that followed, Roman Catholicism was the principal religion.

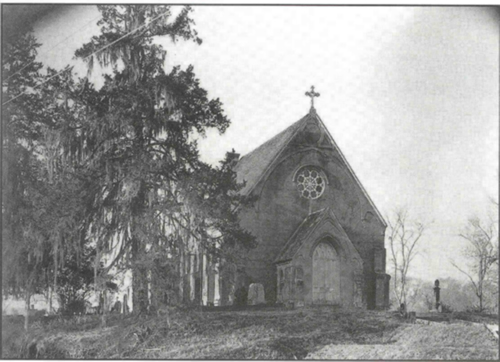

Once Mississippi passed into American hands, however, a new period of religious history began, one marked not by state control of religion but by the supremely American concept of freedom to choose one's religion. Thus, by the time that statehood was achieved in 1817, Mississippi was attracting Methodists, Baptists, Presbyterians, and other Protestant evangelical faiths at a remarkable pace. The first Episcopal church, Christ Church in Jefferson County, was established in 1820 and by 1826, the Episcopal Diocese of Mississippi was organized.

By the 20th century, religion in Mississippi was dominantly Protestant and evangelical.

This article follows religious concepts into the society at large rather than looking at religion as a personal system of belief.

The Great Revival

Evangelicalism began in the 18th-century South as a revolutionary movement among the plain folk. Evangelicalism, first adopted by Martin Luther to describe his break from the Roman Catholic Church, is a broad term that generally refers to Protestant groups that originated in the Anglo-American world during the great religious revivals of the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Born as protest movements, these groups, like the Methodists and Baptists, challenged the domination of the established churches. So powerful was their critique that they attracted large numbers of people alienated from that culture, including women and African Americans who joined in large numbers.

In the early 19th century, a remarkable religious revival began in the backwoods of Kentucky. Known as the Great Revival, it spread outward from its hearth in central Kentucky and blazed across Mississippi as it swept the frontier. The revival brought thousands of converts into the evangelical fold and fueled the rapid expansion of evangelical sects, especially the Baptists and Methodists. Presbyterian churches, however, mostly attracted townspeople and never sought to enroll the masses. The typical evangelical church was a biracial one, and the African American converts greatly influenced evangelical ritual and practice. In these biracial churches a remarkable process of cultural exchange between Black and White people took place.

Spiritual equality

Evangelicals reached out to all members of society, but especially to those most alienated from elite culture. In many ways, evangelicals challenged social stability by upsetting the prevailing hierarchical social relationships. Their message of spiritual equality resonated with women and African Americans. Husbands and fathers often opposed the conversion of the women in their households, and sometimes pressured women in their families to stay away from religious services or to withdraw their memberships.

In a similar fashion, masters often opposed the conversion of their enslaved laborers and remained suspicious of the evangelical stand on slavery. The mingling of Black and White people in camp meetings and other evangelical services challenged their society’s racial mores and the control that masters attempted to exert over their enslaved workforce. The evangelical emphasis on the equality of believers led White evangelicals toward an acceptance of Black people as individuals with souls equal to their own. Despite the opposition of their masters, and probably in part because of it, enslaved people converted to Christianity in increasing numbers and organized independent “African” churches under their own control.

The large and growing number of enslaved African American converts brought the evangelicals face-to-face with America's greatest moral dilemma, the institution of slavery. Early evangelicals, given their stance as committed critics of the evils surrounding them, opposed slavery, a position that almost doomed them in the South. It was a bitter test of their commitment to their most cherished beliefs. By the time they arrived in Mississippi, the evangelicals had largely abandoned any real opposition to the institution, though they continued to criticize abuses within the system.

Change in the churches

The 1830s marked a major turning point in the history of evangelicalism. As the Mississippi economy boomed, more and more of the plain folk moved up the economic ladder and joined the ranks of the slaveowners, and more and more wealthy converts came into the churches. The evangelicals abandoned their stance as cultural revolutionaries and social critics as they grew from small sects to major denominations. The change brought major divisions to all the denominations.

Evangelicals now became the most ardent defenders of a hierarchical social system grounded in slaveholding and patriarchal households. This dramatic shift was reflected in the churches where ritual and practice relegated women and African Americans to more subordinate positions. A century of biracial worship came to an end as Black and White evangelicals divided along racial lines. This brought another major turning point in the history of religion in Mississippi.

Evangelicals were so wedded to their orderly, hierarchical slaveholding republic that they contributed to the disastrous U. S. Civil War that destroyed it. Their impassioned defense of slavery, their own division along sectional lines, and their vision of southern White people as God's chosen people served to undermine their commitment to the Union and helped propel Mississippi into secession and war.

African American Christians, however, had a far different vision of the war and its message. For them, it resonated with the deliverance of the children of Israel from bondage, and it came in answer to heartfelt prayers from enslaved evangelicals.

Social Gospel Movement

The end of the Civil War ushered in one of the most conflicted periods in American history. During Reconstruction, Black people left the biracial churches, created their own religious denominations, and those churches became the largest institutions under Black control and the bedrock of the Black community.

For White denominations, the decades after the war also saw dramatic growth. Indeed, only in the post-Civil War period can the South be considered the nation's Bible Belt. Mississippi Christians embraced many of the humanitarian and social reforms associated with the Social Gospel Movement. The Social Gospel Movement called upon congregations to look beyond the promise of individual salvation to the hope of transforming society. And, Mississippi Christians attempted to use the power of the state to redeem society through their support of temperance and prohibition, hospitals, orphanages, and other benevolent causes.

The post-Civil War years also saw a steady worsening of the racial climate. White Christians were not fully able to bring the power of their faith to alter social practice, though they did serve as practically the only voices of moderation. For Black Christians, their theology, firmly grounded in the doctrine of Christian equality, served as a powerful antidote to racist ideology.

The tensions inherent in Christianity between conformity and revolt reemerged in the post-Civil War period in the Holiness and Pentecostal movements. These movements were perhaps the most dynamic religious movements to appear since the Great Revival. Like the early evangelical movement, these were egalitarian and biracial. Members of the Holiness and Pentecostal sects emphasized the charismatic gifts of the Holy Spirit, relied on biblical primitivism, and disdained material wealth. Though dwarfed by the mainline denominations, these churches unleashed enormous creative and spiritual energies.

Fundamentalist churches

The 20th century ushered in dramatic social, cultural, and economic change, though the extent of those transformations was not always evident at the time. On the surface, religious life ran in familiar channels as the major denominations continued to grow in wealth, membership, and influence. By the 1930s, the Black Baptists had become by far the state's largest denomination with more than twice the membership of White Baptist churches.

One of the hallmarks of American Christianity is its populist appeal, its innovative character, and its churning creativity. While the mainline denominations dominated the state's religious life, powerful challenges to their influence arose from the bottom rungs of the socio-economic ladder as fundamentalist churches sprang up among both Black and White Christians. Churches like the Seventh-Day Adventist, the Assemblies of God, and Church of Christ grew rapidly during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Those churches continued to grow during the Great Depression of the 1930s, but most mainline denominations saw their membership and revenues plummet.

Indeed, it was the Great Depression and World War II in the early 1940s that ushered in changes that fundamentally reshaped the southern landscape, changes even greater than those brought about by the Civil War in the view of many historians of the region.

The demise of the sharecropping system among White and Black people marked a revolution in the state's economic system with equally important implications for the state's social system. New Deal farm programs, established by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in the 1930s, did little to address the needs of the poorest of the poor.

Then, the horrors of World War II revealed the terrible tragedy that racial hatred and injustice produced, and Black and White Christians pointed out the contradictions between American rhetoric and reality. During and after the war, Christians of both races called for an end to racial injustice in the state. In the post-World War II years, African Americans began to mount an aggressive challenge to the Jim Crow system, and the U. S. Supreme Court's 1954 decision in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka gave that challenge a significant boost.

Religion was a major part of the Civil Rights Movement for Black people and for White people. Both proponents and opponents of the Civil Rights Movement understood their stances in religious terms, and both saw themselves as upholding a divinely ordained social order. In many respects, Black and White churches as institutions failed to provide moral leadership in the midst of 20th-century America's greatest moral struggle. Eventually, and with much terror, bloodshed, and heartache, the doctrine of Christian equality, that silver thread running through centuries of church history, proved to be the basis for a consensus among the majority of Mississippians that the day of legal racial injustice had ended.

Non-evangelical religious groups

The huge preponderance of evangelical Protestants among religious people in Mississippi almost obscures the presence of other religious groups in the state, but there were members of non-evangelical religious groups in the state representing important alternative belief systems.

Four of the largest of these groups – Catholics, Jews, Muslims, and Mormons – provide examples of how outsider religious groups function within such a setting. The Catholic and Jewish presence in the state dates back to the colonial period. An examination of their histories reveals that these two groups, so often the object of violent persecution elsewhere, used their religion to overcome their outsider status. In a place where race prejudice overwhelmed all others, Catholics and Jews could conform to the state's racial code, define themselves as White, and thereby integrate into society.

Mormons, more characteristic of earlier movements of religious cultural revolt, often fought conformity but their challenge did not extend to an attack on racial mores. Islam has a long history in the state, though much of the early history of Muslims has been lost. Some enslaved people in antebellum Mississippi were Muslims who held onto to their faith, though it is impossible to know how many such individuals there were. African American interest in Islam rose during the Civil Rights era, and the first Nation of Islam group formed in Jackson in the 1960s. While no firm figures are available, Muslims in the state estimate their numbers at around 4,000, concentrated in urban areas and on college campuses.

Since the upheavals of the 1960s, evangelical religion has further cemented its hold on the region, though with some noticeable changes. As elsewhere across the nation and around the world, fundamentalist churches have expanded most rapidly since the 1970s. Buffeted by drastic social, cultural, and economic changes, Mississippians have sought the comfort of fundamentalist churches, which might be conservative Baptist churches or independent Bible churches. Battles over the teaching of evolution, public prayer in schools, abortion, and homosexuality have divided Mississippians and provide further evidence that the state is very much a part of a national religious scene.

At the beginning of the 21st century, evangelical Christianity continues to dominate Mississippi’s religious life, an outcome that could hardly have been predicted from the fledgling churches that appeared on the Mississippi frontier two centuries before.

Randy J. Sparks, Ph.D., is an associate professor of history at Tulane University, and director of its Regional Humanities Center. He is the author of Religion in Mississippi, from which this article is extracted, and On Jordan's Stormy Banks: Evangelicalism in Mississippi, 1773-1876.

-

Many simple churches, like Toxish Baptist Church in Pontotoc County, dotted the Mississippi countryside from the antebellum period well into the 20th century. Note the separate entrances for men and women. Photo courtesy Mississippi Department of Archives and History. -

The interior of the Toxish Baptist Church. Men often sat on the right, women on the left, and blacks in the rear. Photo courtesy Mississippi Department of Archives and History.

-

First Methodist Church in Columbus. Constructed in 1860, it was home to a large biracial congregation. Photo courtesy Mississippi Department of Archives and History. -

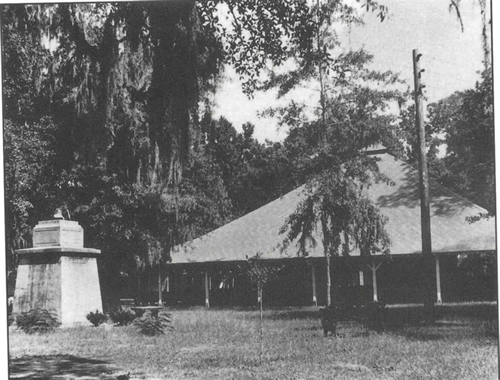

Felders Campground in Pike County. Beginning in the early 1800s, camp meetings helped spread evangelicalism on the Mississippi frontier. Photo courtesy Mississippi Department of Archives and History. -

First Baptist Church in Greenwood (early 20th century). Urban churches like this one indicated the wealth of evangelicals in the state. Photo courtesy Mississippi Department of Archives and History. -

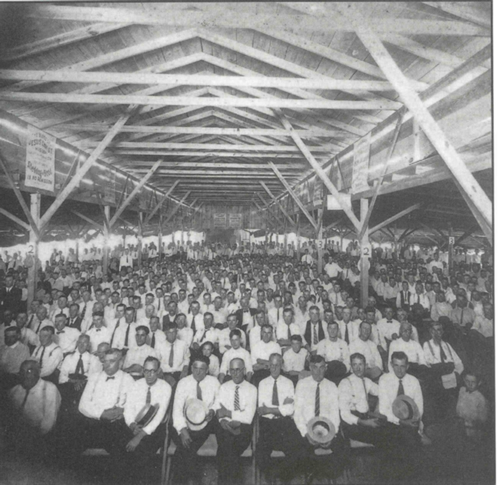

Traveling evangelists filled tent meetings and large meeting halls in the late 19th century. Photo courtesy Mississippi Department of Archives and History. -

Christ Church at Church Hill (mid-1800s) in Jefferson County was the state’s first Episcopal church. Photo courtesy Mississippi Department of Archives and History. -

The Temple Beth Israel congregation worshiped in this building from 1942 to 1967. Photo courtesy Mississippi Department of Archives and History.

Selected bibliography

Cotton, Gordon A. Of Primitive Faith and Order: A History of the Mississippi Primitive Baptist Church, 1780-1974. Raymond, Miss.: Keith Press, 1974.

Hill, Samuel S. editor. Encyclopedia of Religion in the South. Macon, Ga.: Mercer University Press, 1984.

McLemore, Richard Aubrey. A History of Mississippi Baptists, 1780-1970. Jackson: Mississippi Baptist Convention Board, 1971.

Mathews, Donald G. Religion in the Old South. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 1977.

Miller, Gene Ramsey. A History of North Mississippi Methodism, 1820-1900. Nashville, Tenn.: Parthenon Press, 1966.

Niebuhr, H. Richard. The Kingdom of God in America . 1937 reprint, Middletown, Conn.: Wesleyan University Press, 1988.

Sparks, Randy J. On Jordan’s Stormy Banks: Evangelicalism in Mississippi, 1773-1876. Athens, Ga., and London: University of Georgia Press, 1994.

_______. Religion in Mississippi. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi for the Mississippi Historical Society, 2001.

Wilson, Charles Reagan. Baptized in Blood: The Religion of the Lost Cause, 1865-1920. Athens, Ga.: University of Georgia Press, 1860.

________, editor. Religion in the South. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1985.