The 1964 Mississippi Freedom Summer was perhaps the most ambitious extended campaign of the entire Civil Rights Movement. Over the course of roughly two months, more than 1,000 volunteers arrived in Mississippi to help draw media attention to the state’s Black freedom movement, to register African American voters, and to teach in Freedom Schools that were established to supplement the inferior educational opportunities provided to black youths in the state’s public schools.

Educational Disparities

Ten years after the decision in Brown v. Board of Education (1954), most Southern school districts remained racially segregated due to massive White resistance and the federal government’s delay in clearly defining and enforcing the process of the racial integration of the nation’s public schools. Adamantly opposed to desegregation, White Mississippi legislators tried to prevent school integration by providing more resources for African American schools. Throughout the middle and late-1950s, the state finally built new buildings for Black schools, renovated deteriorated and dilapidated classrooms, and purchased more busses, textbooks, and a variety of other educational materials, all in an effort to prove that African Americans had access to a quality education. However, these last minute, token gestures did not come close to balancing the enormous disparities between Black and White schools that had existed for generations in the state. As late as 1960, Mississippi was spending an average of approximately four times as much on White pupils as African American students. Some individual school districts were even more unbalanced. In 1962, for example, the Tunica County School District spent an average of $172.80 on each White pupil but only $5.99 on each of their Black counterparts. That same year in Clarksdale, the amount spent on each White student was $146.06 compared to $25.07 for each Black student. By the time civil rights activists began planning Freedom Summer in the early 1960s, African American students still attended inferior schools and generally had far less access to basic educational resources than White students. Moreover, the curriculum and faculty at many Black public schools were closely monitored to prevent teachers from discussing or promoting certain aspects of African American history or the Civil Rights Movement, or from joining organizations such as the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).

Decades of educational disparities wrought devastating economic consequences for Black Mississippians. Although most could read and write, fewer than five percent of Black Mississippi adults held a high school diploma in 1964. Many did not know basic facts about the government of the United States of America, such as how many states were in the nation, the purposes of the three branches of federal government, or that Black people had been guaranteed the right to vote by the Fifteenth Amendment. Many White Mississippi schools also struggled mightily, and the state lagged behind most of the rest of America in high school graduation rates. However, the disproportionate resources afforded to Black Mississippi schools had been specifically designed to maintain a relatively uneducated and politically inept labor force that undergirded a commitment to White supremacy. A handful of extremely well educated Black doctors and teachers helped develop pockets of resistance and some strong classrooms for African American youth, but across the state, many Black Mississippians in the early-1960s remained woefully undereducated about their own basic civil and political rights.

COFO and Freedom Summer

In 1961, representatives from a variety of civil rights organizations began working aggressively with local Black Mississippians for the right to register to vote. These groups—the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), the NAACP, and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC)—came together under an umbrella organization named the Council of Federated Organizations (COFO). COFO coordinated public protests and voting rights campaigns across the state, encountering some encouraging successes, but also experiencing devastating setbacks, due to persistent economic intimidation and racial violence. To break the deadlock, COFO in 1964 planned a civil rights campaign of unprecedented scale. That summer, the organization recruited as many as 1,000 outsiders into Mississippi to help register the state’s African American voters, to draw attention to the violent suppression of civil rights activities in the state, and to teach civil rights to the youth of Mississippi in local Freedom Schools.

COFO activists designed Freedom Schools to empower and motivate underprivileged Black students. Freedom Schools were largely modeled on the Highlander Folk School in Tennessee, which had for decades served as a major training center for labor and civil rights activists. Highlander’s philosophy reflected that of veteran civil rights leader, Ella Baker, who was famous for saying, “strong people don’t need strong leaders.” As opposed to following the leadership of a minister or charismatic speaker, the Highlander philosophy called for all people to become active agents in their own liberation. The Freedom School curriculum and pedagogy reflected that approach. Students were given both the opportunity and responsibility to shape their processes of learning and liberation. Unlike other schools where mandatory attendance and examinations coerce student involvement, the Freedom Schools were voluntary and provided the young African Americans with an experience that was immediately relevant to their own lives. Freedom School teachers were trained to ask students questions and challenge them to find their own solutions.

1964 Mississippi Freedom Schools

The 1964 Mississippi Freedom Schools opened on July 2, the same day President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act. COFO Freedom School organizers had initially planned for about 1,000 students, but by the end of the summer, the schools drew an estimated 2,500 to 3,000 students. The six Freedom Schools in Hattiesburg alone had over 600 students. Meridian was the largest, single Freedom School with more than 200 regular students. Freedom Schools were organized in municipalities throughout the state, including Batesville, Canton, Columbus, Gulfport, and Jackson. All told, at least forty-one Freedom Schools operated across Mississippi during the 1964 Freedom Summer. Students ranged in age from five to eighty, but most were between ten and eighteen years-old.

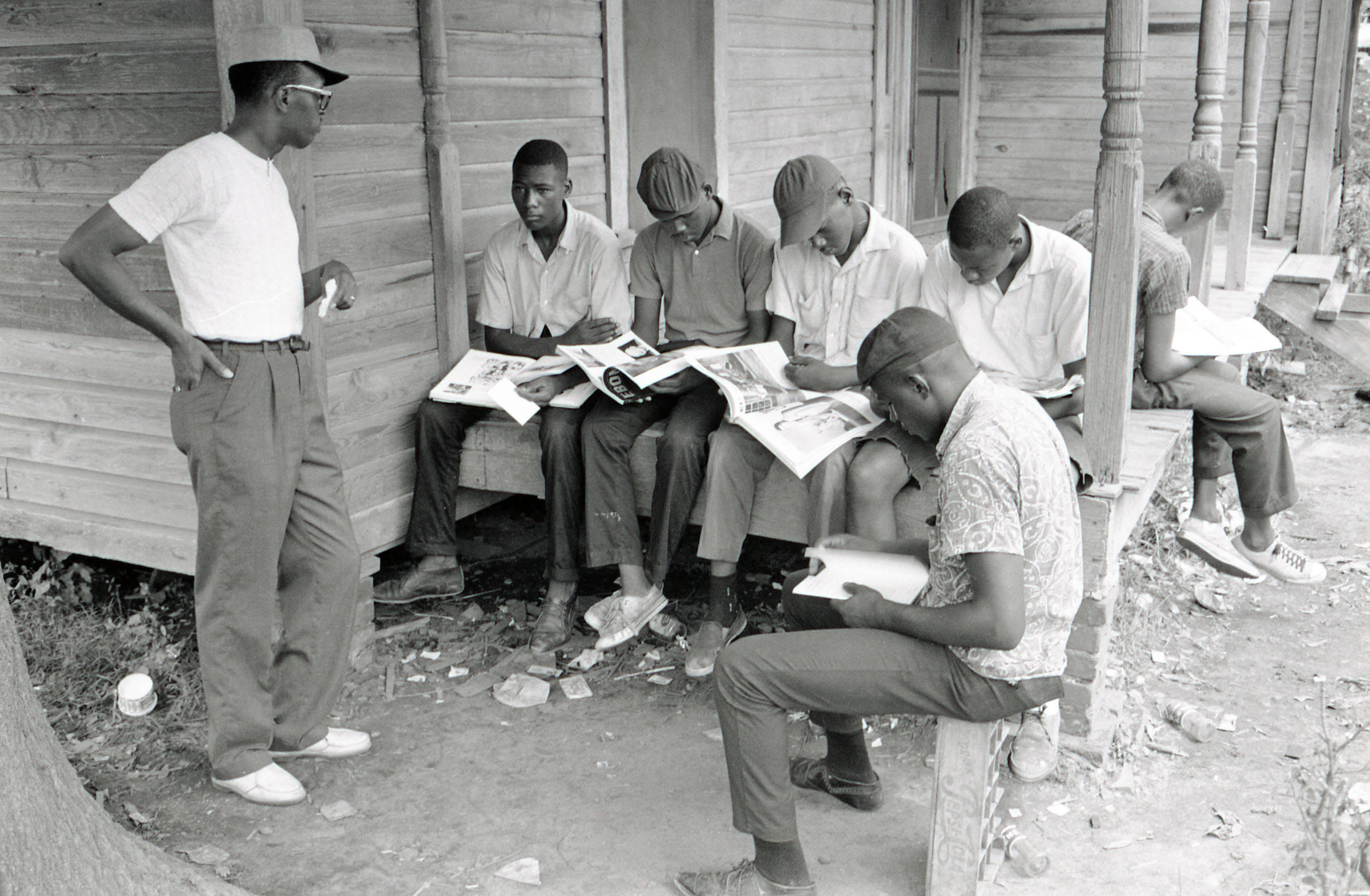

A typical day in Freedom School began within the singing of Freedom Songs to invigorate students and teachers. From there, the Freedom School curriculum varied widely by school and classroom. Some students were most interested in learning remedial skills in arithmetic, writing, reading, and even French. Many were drawn to African American magazines such as Ebony or Jet and novels by Black writers such as Richard Wright that featured colored photographs of influential African Americans and told stories from black perspectives. Freedom School students were also deeply interested in learning about historical figures such as Harriet Tubman and Frederick Douglass and used these heroes from the past to draw parallels to their own processes of liberation. Some classroom activities offered even more direct connections to the Civil Rights Movement, asking students to comment on goals and tactics and encouraging them to debate movement strategies such as non-violence versus armed self-defense.

Written expression was crucial to the Freedom School experience. Through poems, short-stories, essays, and even theatrical productions, Freedom School students shared their feelings toward Jim Crow segregation laws and practices and asserted their desire to claim liberation and equality. Students in at least fourteen Freedom Schools published their own civil rights newsletters that contained an array of creative literary works and updates about local movement activities. The newspapers, which were distributed in the local Black community, were filled with the encouraging words of Freedom School students who challenged their elders into action and resolved to fight for equality the rest of their lives.

Freedom School Students

Enthralled with the movement, many Freedom School students became active participants and leaders. Attending Freedom Schools alone was a political act, but students went even further, attending mass meetings, canvassing potential voters, joining protest marches, and writing letters to government leaders, such as the governor of Mississippi and even President Johnson. In McComb, a group of young teenagers organized a program to help older African Americans learn how to complete voter registration cards, and all across the state, young, Black Freedom School students conducted sit-ins at local libraries, restaurants, and department stores to test the newly passed Civil Rights Act of 1964. Many of these developing leaders helped guide the direction of local protests after many of the outside volunteers left the state at the conclusion of Freedom Summer.

In early August, Freedom School students helped organize a statewide Freedom School Convention in Meridian where delegates from across the state held a two-day meeting to discuss the primary issues facing Black Mississippians. Splitting into a series of subcommittees, the young Black leaders analyzed specific sets of problems such as employment, housing, voter registration, and medical care. They even drafted a series of resolutions designed to improve these issues.

Across Mississippi today, there are hundreds of former Freedom School students whose lives were changed during their experiences in the summer of 1964. Many of them went on to become teachers, social workers, lawyers, and lifelong activists. Some were among the first to integrate Mississippi’s public schools the following autumn. Even those who did not become civil rights activists or community organizers finished that summer with a new sense of expectations about their civil and political rights. For virtually all who attended, Freedom Schools served as a powerful moment of intellectual liberation. One of the most important legacies of the 1964 Mississippi Freedom Schools extends beyond the original students. Today, thousands of Freedom Schools are held across the United States of America each summer. Conducted in a new era, they differ in many ways from the Mississippi Freedom Schools, but they can trace their intellectual and spiritual roots to those Mississippi Freedom Schools that operated in the summer of 1964.

Dr. William Sturkey is an assistant professor of history at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. His work has appeared in the Journal of Mississippi History and the Journal of African American History. He, along with Dr. Jon N. Hale, assistant professor at the College of Charleston in South Carolina, edited To Write in the Light of Freedom: The Newspapers of the 1964 Mississippi Freedom Schools.

Other Mississippi History NOW articles:

Aaron Henry: A Civil Rights Leader of the 20th Century

The Last Stand of Massive Resistance: Mississippi Public School Integration, 1970

On Violence and Nonviolence: The Civil Rights Movement in Mississippi

When Youth Protest: The Mississippi Civil Rights Movement, 1955-1970

Lesson Plan

-

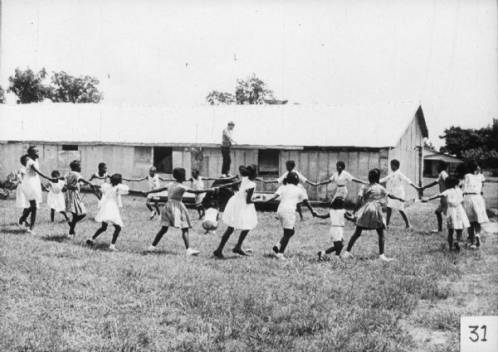

Photograph of children playing a game outdoors as a part of a Freedom School activity. Courtesy of the Wisconsin Historical Society, image number 97888. -

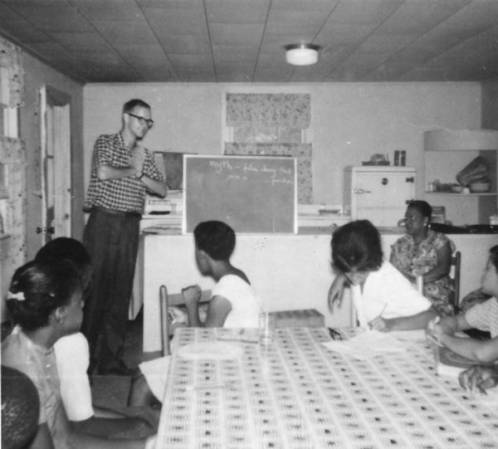

Photograph of a white male Freedom Summer volunteer teaching African-American students in a Freedom School in Priest Creek Baptist Church. Courtesy of the Wisconsin Historical Society, image number 97469.

-

Photograph of a group of African-American children pose outdoors on and in front of a pickup truck during Freedom Summer and likely at the Freedom School at Priest Creek Baptist Church. Courtesy of the Wisconsin Historical Society, image number 97475. -

Photograph of a group of teenaged male Freedom School students sitting on and near the porch of a house on Gravel Line Street reading issues of Ebony magazine. Volunteer Arthur Reese (Detroit, Michigan, school principal), Co-Coordinator of the Freedom Schools in Hattiesburg, stands talking to them. Courtesy of the Herbert Randall Photographs Digital Collection at the University of Southern Mississippi Digital Collection, mus.m351.0484p. -

Photograph of legendary folk singer and social activist Pete Seeger performing for Freedom School students, local residents, and volunteers in the community center established by Freedom Summer participants at Palmers Crossing in Hattiesburg on August 4. Two young people in the audience are Clarence Clark (second row, far left) and Carolyn Moncure (toward the rear, right side). Courtesy of the Herbert Randall Photographs Digital Collection at the University of Southern Mississippi Digital Collection, mus.m351.0779p. -

Photograph of the view of the audience at the MFDP lecture given by SNCC Field Secretary Sandy Leigh (New York City), Director of the Hattiesburg Project, to Freedom School students in the sanctuary of True Light Baptist Church. Some of the Freedom School students are Sandra Blalock, Ann Conner, Rena Corley, Audrey “Pee Wee” Easterling, Myrtis Easterling, Beverly Harris, James Townes, Alma Travis, Janice Walter, Shirley White, and Jerry Wilson. Three volunteers who taught in the Freedom School at True Light are: William D. Jones (a native of Birmingham, Alabama and a teacher in the Long Island, New York public schools), who is standing gesturing from a rear pew; Nancy Ellin (from Kalamazoo, Michigan), sitting next to him; and Peter Werner(from Flint, Michigan, and a graduate student at the University of Michigan),the Caucasian male seated in the fourth pew from the camera. Courtesy of the Herbert Randall Photographs Digital Collection at the University of Southern Mississippi Digital Collection,mus.m351.0296p

Sources and suggested readings:

Adickes, Sandra. The Legacy of a Freedom School. New York: Palgrave McMillen, 2005.

Bolton, Charles. The Hardest Deal of All: The Battle Over School Integration in Mississippi, 1870-1980. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2007.

Dittmer, John. Local People: The Struggle for Civil Rights in Mississippi. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1994.

Hale, Jon N. The Freedom Schools: A History of Student Activists in the Mississippi Civil Rights Movement. New York: Columbia University Press, 2016.

Moses, Bob. Radical Equations: Civil Rights from Mississippi to the Algebra Project. Boston, MA: Beacon Press, 2002.

Payne, Charles. I’ve Got the Light of Freedom: The Organizing Tradition and the Mississippi Freedom Struggle. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995.

Sturkey, William and Hale, Jon N. eds. To Write in the Light of Freedom: The Newspapers of the 1964 Mississippi Freedom Schools. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2015.