In the years after the American Civil War, famous generals and common soldiers alike published their remembrances. These accounts appeared in books, in magazines, and, as was the case here, in newspapers. The press created Civil War series such as the one reprinted here from the New York Tribune. The most famous of all these series appeared in The Century Magazine and in the late 1880s was published in four volumes under the title Battles and Leaders of the Civil War. (In 2002, a fifth volume was added to the original four.)

What follows here – “The Affair on the Raymond Road” – is an excellent example of this kind of writing. Henry O. Dwight, the adjutant of the 20 Ohio Regiment (Colonel Manning Force), 2nd Brigade (Brig. Gen. Elias S. Dennis), Third Division (Maj. Gen. John A. Logan), XVII Corps (Maj. Gen. James B. McPherson), Army of the Tennessee (Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant), discussed his unit’s experiences in the Battle of Raymond, May 12, 1863, a part of the Vicksburg Campaign.

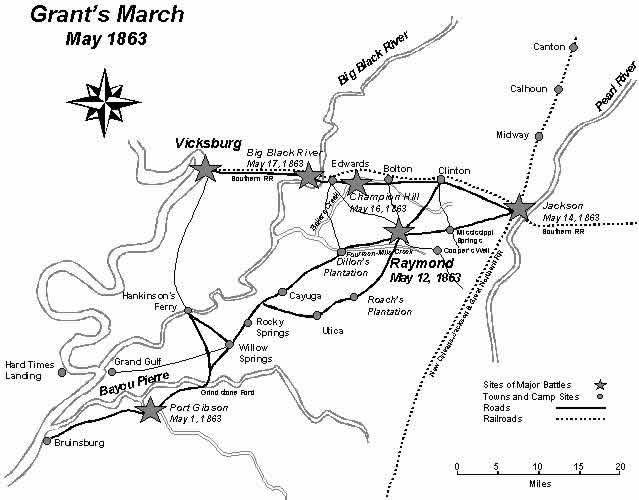

This series of battles, of which Raymond was but one part, saw Union General Grant brilliantly out-maneuver Confederate Lt. Gen. John C. Pemberton and Gen. Joseph E. Johnston and capture Jackson and then Vicksburg, Mississippi. Many historians believe the fall of Vicksburg was the most significant Union victory of the war

Lieutenant Dwight’s account of the battle of Raymond presents an excellent idea of how combat looked to the individual soldier. Since he wrote his newspaper article twenty-three years after the event, he was able to put his experiences into a broader context, something that the individual soldier could not do at the time of battle.

Dwight used several phrases and comments that are racist and insulting to the modern ear, but they do provide a good insight into White society’s anti-Black attitude during the late 19th century.

Three other words that might need explanation are “Libby,” a reference to the over-crowded Libby Prison in Richmond, Virginia, one of the places where the Confederates kept Union prisoners of war. “Meerschaum” refers to a tobacco pipe made of hard white mineral. Dwight’s reference to “football” demonstrates the popularity of this new American game, just then being developed out of soccer and rugby.

John F. Marszalek, Ph.D., W.L. Giles Distinguished Professor Emeritus, Mississippi State University, and executive director and managing editor, The Ulysses S. Grant Association.

New York Semi-Weekly Tribune

Friday, November 19, 1886

New Stories of the War Told by Soldiers and Sailors XXXIV

“The Affair on the Raymond Road”

By Henry O. Dwight

First Lieutenant and Adjutant 20th Ohio veteran, voluntary infantry

If you want to find fault with any one for getting up such a fuss on the Raymond Road on that day I may as well tell you at the outset that they began it. All that we wanted was to be left alone.

We had crossed the Mississippi with the rest of General Grant’s army, had taken a part in the fight at Port Gibson, had chased the enemy over Bayou Pierre toward Grand Gulf, General Grant riding ahead of everybody sometimes, so anxious was he to come up to the columns that were running away from us. We had reached the Big Black River at Hankinson’s Ferry and had sat there for several days looking at the Rebs on the other side of the river, taking an occasional pot shot at them when they came too near the bank, and getting waked up in the morning occasionally by their shells coming into our camp. We had stayed at Hankinson’s Ferry until we were tired of it and the Rebs got tired of us, thinking we were going to try to cross. For that matter we thought so too, for all the skiffs in the country were got together and roads were out to the water at various places.

At last one day we received orders to pack up and march off into the country, leaving the Rebels to watch our camp for us. We took the Raymond Road, and by looking at the maps we all saw that if we kept on long enough we should come out on the railroad between Vicksburg and Jackson, and have the first pick of old Pemberton’s supply trains as they came in on the railroad. This march took us away from the Rebels and we were not sorry for that. There was nothing about us that looked like wanting a muss. All we wanted was to go peaceably along the road until we reached the railroad, and then they might do as they liked about it.

The weather was splendid, the roads were in fine condition and there was plenty to eat in the country. It is true that we were more conscientious about taking what we wanted then than we were after we had made the march to the sea. For instance, one day we came to an old woman’s house where there was a quantity of honey. It was just a little way from our camp and we thought that a little of the honey would do us good. So (don’t laugh) we undertook to buy the honey. The row of beehives was as tempting to us as a melon patch to a six-foot negro.

The old woman said she never sold less than a hive.

“Well, what will you take for a hive?” I asked, taking out a roll of bills to show that I meant business.

“’F you uns want the honey ye c’n hev it for twenty dollars. There’s right smart in that there mug,” she added, pointing to one of the hives.

“Twenty dollars!” said I, rather aghast.

“Yes, and I don’t want Yankee greens, neither,” said the old woman, with a scornful jerk of her thumb at my roll of bills. “I want money.”

“What sort of money do you want?”

“I want the real Confedrit bills. That there stuff ain’t no ‘count here.”

“Oh, you want Confederate money, do you? Well, I can accommodate you,” said I, giving her a Confederate fifty-dollar bill, for which she gave me thirty dollars in change. Then we went for the honey and had a regular picnic that night.

The next morning, May 12, we went on our way, feeling peaceable to all the world, as I said, Logan’s division had the advance and our regiment, the 20th Ohio, led the division, leaving camp about daybreak. In a few minutes we passed the house where we had bought the honey, and the old woman was there, leaning on the fence smoking her cob pipe and watching the troops go by. When she saw me she said: “Ye’n be back this way before long. They’re waiting for you uns up yonder.”

This raised a laugh in the column, for we had seen no Rebs for several days and we knew very well that Pemberton was keeping them all on the other side of Big Black against we got ready to try a crossing.

The road lay through woods and fields, passing few houses, and what there were were as still as a farmhouse in haying time. Sometimes we saw a few little niggers, who stood grinning at the men, or if the music happened to be playing they danced to the sound of the fife, for all the world as if they could not help it if they tried. Sometimes an old negro woman would appear, bowing and smirking, and then when the first embarrassment had worn off like she would say: “Lord a masay! Be there any more men where you uns come from? ‘Pears like as if I nebber saw so many men since I’se been born.”

At this, some one would be sure to give the regular answer in such cases made and provided: “Yes, aunty, we come from the place where they make men.”

After a while, as we were marching quietly along, we heard two pops, which we were able to recognize as gunshots, far on in front.

“Hello, somebody is shooting squirrels,” said one of the boys.

“Pop, pop, pop,” came three more shots in quick succession, but a little nearer.

“The squirrels are shooting back,” growled a burly Irishman, “and sure it’s meself that don’t approve of that kind of squirrel shooting, not a bit of it.”

A squad of cavalry was in front of us to scout the road for the infantry column, and it was none of our business if they chose to shoot away their ammunition.

But after we had been out two hours or so, while we were halted to take breath a bit, a cavalryman came in from the front and handed a message to General Logan. The General then mounted his horse and rode on out of sight. When we moved on, we soon came up with him, standing by the side of the road, and he gave some sort of an order to General Dennis, who was temporarily in command of the brigade. What all this mysterious business of General Logan’s was we could not imagine, but almost instantly our regiment was halted and the Colonel ordered it to deploy as skirmishers on both sides of the road.

Of course we felt solemn when we were ordered to deploy, for it suggested a disagreeable meaning to the shots which we had heard. The road lay through the very thickest kind of woods, and you couldn’t see a rod, so that it took something like a half hour to get the boys all strung out in their places, ready to go on. The line was like enough three-quarters of a mile long, and you couldn’t see more than three men at a time in any part of it. It was enough to make a person swear when the bugles sounded forward, and that huge line had to try to keep some sort of an alignment. The trees and underbrush were covered with thorny vines which trailed in tangled chains from branch to branch. Great moss grown trunks of fallen trees had to be climbed over; old stumps, burned out by the fires of ancient hunters, left deep pit-falls that a fellow couldn’t leap and that had to be circumnavigated, even if the act did bring three or four men into Indian file when they ought to have been scattered out like as many ants. After passing such an obstacle it was always some minutes before the line could could find itself again. Sometimes it could not find itself, and a halt had to be sounded, when a hundred men or so would be found to have parted from the rest, like an uncoupled freight train, and to be busily scouring the country behind us. Then there would be a great expense of time, breath and strong language, in trying to get the ends of the broken line together.

By the time we had had two hours of this kind of work our solemn feelings, felt on taking the formation that implied nearness of an enemy, had all given place to the fiercest wrath toward the cavalry scouts who had given such reports as to lead us into this sort of work. If they had really seen any Johnnies, to send our immense line of skirmishers into the woods after them was like turning town meeting into a raspberry batch to catch a chipmunk. Certain it is we never saw hide nor hair of a Reb all that morning. At last General Logan saw that the main column could not march unless our long skirmish line could be got out of its way, and he ordered the skirmishers to be brought in. Two companies were then deployed as skirmishers next to the road and the rest of the regiment was made to march in line of battle behind them, ready to support them if need be. We all knew perfectly well that it was only a scare, for we had sifted the country for Rebs as one might sift the dirt for diamonds. However, we could do nothing but grumble, as we pushed on through that terrible undergrowth, until after noon.

By that time we were thoroughly tired out. At last we came to a little clearing, of ten or fifteen acres, in the woods, and for the first time caught sight of our own formation. The cavalry scouts were halted at the further side of the clearing, in the shade of the trees, and our own skirmishers were halted about on a line with them, wiping the sweat off their faces as they stood fanning themselves in the shade. A staff officer was waiting for us as we came out of the woods with the order to halt in the clearing and to rest for lunch. General Logan was over in the road near the cavalry, dismounted and getting ready for lunch too, first sending the cavalry off on a byroad to the left.

It was evident that the scare about rebels, whatever it was, was over, and that we were to march like white men from this on. But we were halted in the open field, in the full blaze of sun. As we stacked arms, Johnnie Stevenson said: “Boys, I wish I was in my father’s barn.”

“Why?” asked somebody, who wanted the facts in every case. “What would you do there?”

“I’d mighty soon get into the house!”

This echoed the feelings of the regiment as we halted in that Southern sun. But the General took pity on our condition, and he ordered the skirmish line to be moved forward a few paces, and had us take arms again and move up to the edge of the woods, where was a little brook in the shade of the trees. There we stacked arms in luxury and filled our canteens at the brook, or poured the cool water over our heated faces.

As we lay on the ground at the brook, taking our ease soldier fashion, the boys were grumbling, chaffing, munching hard tack, or making fires to boil coffee in their tin cups. The other regiments of the brigade came up, an Indiana regiment going into line along the edge of the woods on our right, and the 78th Ohio taking the place on our left, with the 68th near by. De Golyer’s battery of artillery, which always marched with us, stopped in the road near the skirmish line, and two of the guns were pointed down the road, in case any inquisitive chap should be coming from the other direction to see what we were about. Some of our boys sauntered off toward the road to try and find out what the cavalry had seen to put us to the trouble of marching in line three mortal hours. The whole country was still with the stillness which you only see at nooning after a hard day’s work in the fields. The grass where we lay was sweet with clover, and a few wild flowers showed their heads here and there. In the woods not very far away a mocking bird was singing. Near where I was an old dead tree had fallen over on to the big arms of one of its neighbors, and on one of its decaying branches a red squirrel popped up its head, looking down at us along the brownish streak that marked his usual highway to the ground.

“Bang cr r r r r rang! Bang cr r r r r r rang!” came the two shells from the peaceable country in front, bursting over the heads of the groups in the road. There was a running to and fro, and almost immediately De Golyer replied with his two guns to this sudden challenge of the enemy whose existence we had just been disputing. We all jumped, of course, every man feeling as he hadn’t felt since the last time he was caught stealing apples. But we hadn’t time to more than turn our heads when from out of the quiet woods on the other side of the brook there came a great yell, of thousands of voices, followed by such a crashing roar of musketry as one doesn’t very often hear unless he has been prepared for it.

“Attention, battalion, take arms, forward march,” shouted Colonel Force, and we all blessed him for knowing exactly what to do, and for doing it. As one man, the boys seized their guns -- some were barefoot, for they were washing their feet in the brook; some had the coffee in their hands which the first scare had made them clutch from the fire; and some twenty or thirty were dead or wounded from that first volley. But quick as thought, all who could stand had taken their guns and plunged through the brook. On the other side, not fifty yards distant, the enemy were crashing through the underbrush in a magnificent line determined to carry all before them.

Two brigades of Texas troops had been watching our movements all the morning, and when we stopped for our nooning their pickets were not a hundred yards from our skirmish line. The moving of our main line to the edge of the woods without sending skirmishers on in front had given them their chance for a surprise. Three regiments had come quickly to the thicket in front of us, got all ready, and made their rush with seven or eight other regiments backing them up.

On our side, our own brigade happened to be in line, but was not expecting any such unprovoked assault. What cavalry we had, had been sent off to the left to take a look at things toward the Big Black where, after all, the chief danger seemed to be. De Golyer’s battery was watering its horses so near to the skirmish line that if the infantry was driven back an inch, it would be captured by the swarming rebels long before help could be got from our other brigades, for the other two brigades of our division were scattered along the road, just where they happened to be when they received the order to halt for lunch.

At the first rush the rebel line far outflanked the Indiana regiment on our right and the whole regiment broke into inch bits, the boys making good time to the rear. This left the Johnnies a clear road to pass our flank, and they made good use of their chance, working well to our rear before long and putting bullets into the reverse of our line the best they knew how. At this moment the fate of the brigade, and certainly of our battery down there in the road, depended on the possibility of our holding those fellows at bay until the other brigades could be brought up.

When we rushed through the brook we found the enemy upon us, but we found also that the bank of the brook sloped off a bit, with a kind of a bench at its further edge, which made a first-rate shelter. So we dropped on the ground right there, and gave those Texans all the bullets we could cram into our Enfields, until our guns were hot enough to sizzle. The gray line paused, staggered back like a ship in collision which trembles in every timber from the shock. Then they too gave us volley after volley, always working up toward us, breasting our fire until they had come within twenty, or even fifteen paces. In one part of the line some of them came nearer than that, and had to be poked back with the bayonet.

It was the 7th Texas which had struck us, a regiment which had never been beaten in any fight. We soon found that they didn’t scare worth a cent. They kept trying to pass through our fire, jumping up, pushing forward a step, and then falling back into the same place, just as you may see a lot of dead leaves in a gale of wind, eddying to and fro under a bank, often rising up as if to fly away, but never able to advance a peg. It was a question of life or death with us to hold them for we knew very well that we would go to Libby -- those that were left of us -- if we could not stand against the scorching fire which beat into our faces in that first hour.

Meanwhile the Johnnies sent in another regiment on our left to pick up De Golyer’s battery, as a kind of a pastime like. But the battery had given back a little, for the sake of a better ground, and when the Johnnies tried to go there they got the fire of the 78th and 68th, besides as much canister as they could digest for one while. So they concluded that they would not take DeGolyer, just then. General Logan sent all his aids on a run down the road for the other brigades of the division, while he himself made a rush for the Indiana regiment which was falling back from our right, and got the boys to face about and take position where they could pepper the Rebs who were firing into our flank and rear. General Logan knew that he had the whole corps behind him, and McPherson was already on hand, sending back to Crocker to hurry up his division; but he also knew that this sort of thing -- the piling of ten rebel regiments on to three or four of his regiments -- could not go on very long. So the other brigades seemed to him a terribly long time in getting up.

In the midst of all this anxiety one of the staff came back to General Logan from one of the wished for brigades and said: “General ____ will be here before very long. He says that he will start as soon as his men have finished their coffee.”

Even in the hurry of that rough time, this answer made General Logan stop and stare. His feelings were too deep for proper utterance. He only said, “Go tell General ______ that he isn’t worth h__ room,” and rode off to place the regiments of the First Brigade which now began to come up.

The staff officer mounted his horse and galloped down the road. He is said to have given Logan’s message word for word. I am sorry to say that I have not the papers to prove this statement, but it was believed by all the boys at the time, and if it was not true it ought to be.

All this time we were hanging on to the bank of the brook with those fellows pouring gunpowder smoke into our faces, and we answering back so fast that the worst game of football is nothing to the fatigue of it. As for the noise of that discussion between the 20th Ohio and the 7th Texas, a clap of thunder is nowhere. It was more like a sheet of thunder, a wicked roar with no separations between the bolts, and all the time the Johnnies made it hot for us in flank and rear as well as in front.

The Johnnies seemed rather to like it. We could see them tumble over pretty often, but those who were left didn’t mind it. One officer, not more than thirty feet from where I stood, quietly loaded up an old meerschaum, lit a match, his pistol hanging from his wrist, and when he had got his pipe well agoing, he got hold of his pistol again and went on popping away at us as leisurely as if he had been shooting rats. Why that fellow didn’t get shot I don’t know. The fact is when you start to draw a bead on any chap in such a fight you have to make up your mind mighty quick whom you’ll shoot. There are so many on the other side that look as if they were just getting a bead on you that it takes a lot of nerve to stick to the one you first wanted to attend to. You generally feel like trying to kind of distribute your bullet so as to take in all who ought to be hit. So a good many get off who are near enough to be knocked over the first time.

We could not understand why somebody wasn’t sent out to cover our flank in place of the Indiana fellows. It seemed as if we were forgotten. So when they sent us some ammunition it was like a gift from distant friends, and did us good like a reinforcement. It was quite as well that we did not know that the first of our two rear brigades had come up and had deployed on the right of the rallied Indianians, but that even then Logan found himself outnumbered two to one. The fellows on the right kept the Rebs from scooping us up, but could not get forward enough to cover our flank, and had to fight like everything to hold their own. So we were left sticking out like a sore finger for the best part of another hour. There were only nine companies of us, and out of those about the number of one company had been killed or wounded. Two companies, “A” and “I,” were out on the skirmish line when those chaps rose up and charged. Hao Wilson, of Company I, managed to assemble his men from between the two lines of fire and brought them in. But Weathersby, of Company A, was not so fortunate. The length of the line of skirmishers had taken him well to the right, so that when the affair commenced he was cut off from us by the Rebs who got on our flank, and he and his men were left in the air, like Noah’s dove, without rest for the soles of their feet, until they managed to join the 81st Illinois in the brigade that went in on that flank, and fought as part of that regiment for the rest of the battle, but their good fighting there did not alter the fact of there being but nine companies of us in that thicket, exchanging our hot lead for Texas hot lead as fast as either side could put it in, and becoming fewer and fewer all the time, as the numbers lying in the pools of blood became more and more.

The brook bank protected us some. The leaves and twigs mowed from the bushes by the Texan bullets fell softly about us, but those fellows shot to hit and not to cut twigs about our ears. Captain Kaga got his collar bone and shoulder blade splintered and badly mixed. Johnny Stevenson wanted to be in his father’s barn more than ever when a half inch of lead had ploughed a hole through his neck. One of the sergeants shouted to me as I stood beside him, but I could not hear. He was loading his gun, and he roared again in my ear, “They’ve got me this time sure, but I’m going to have one more pop at them.” He took careful aim and fired, and fell backward into the brook, with a bright red hole in his shoulder. Then I understood what he meant. Company C lost its officers and was commanded at last by a high private named Canavan, who managed things like a West Pointer. Most of the men killed were shot through the head and never knew what hurt them.

Well, the short of it is, it was a pretty tough time that we had of it, lying there by the brook and digging our toes into the ground for fear that the mass of men in front would push us back over the bank after all. But every man held to his place, for every one felt as if there was a precipice behind and he would go down a thousand feet if he let go his hold on that bank.

At last the rear brigade of our division got up, and Logan sent them in on the right where the Johnnies were again ready to make a flanking rush. Our fresh brigade went in with will and effect. They didn’t wait for much ceremony, but just felt their front with a few sharp volleys to kind of get the temper of the chaps, and then they charged like men who had had their coffee. We heard their cheer, but we didn’t hear the angry burst of musketry with which the Rebs replied to it, nor the noise made by our other brigade as it came up on the line with us.

Pretty soon we found the Rebs in front of us were edging off a bit. Somehow we were not pressed so hard. The firing kept up, but the smoke did not puff into our mouths so much. More twigs and leaves were hit and fewer men. Then we began to hear the bullets for the first time. The Johnnies were farther away. Then there was nobody left to shoot and our own fire stopped. Now we could stand up and stretch our legs and rinse the charcoal and saltpetre out of our mouths of the muddy brook. I looked at my watch. We had been at work on those Texans near two hours and a half, although I must say that after it was over, it did not seem more than an hour.

We were a hardlooking lot. The smoke had blackened our faces, our lips and throats so far down that it took a week to get the last of it out. The most dandified officer in the regiment looked like a coalbeaver.

But there was no time to be thinking about looks. “Attention battalion, forward march,” came the order of Colonel Force again, and away we went with a shout, over the ghastly pile of Texans who had been laid along their line by our fire. Shortly we came out into a big cornfield beyond the woods, and the first thing I saw on the ground was the meershaum which the Rebel officer had smoked in the fight. It was still warm as it lay where it had dropped from his mouth when he ran, and I picked it up and took my turn at smoking it. In front of us was a bare ridge and over this the Rebels were retiring in a bulging and shaky line, pelted by De Golyer’s best shrapnel and pestered by the rifle fire of our Third Brigade boys. The affair on the Raymond Road was over.

There was a big dinner in the town hall at Raymond which the ladies of the town had got ready to refresh the Johnnies on their return from the fight. But the Johnnies hadn’t time to indulge at the time of their return. In fact, they had gone a good distance beyond the town without stopping before the good people of Raymond understood the strategic move which was in progress. The dinner was quite as useful to the Yanks, who had time to eat it, as it could have been to the Rebs.

The next day we had the railroad which supplied Vicksburg, and the day after, the 14th, we met our Texas friends again when we went to back up Crocker’s division in the grand rush which sent them and the rest of Joe Johnson’s army flying through Jackson. Then we turned toward Vicksburg, and on the 16th beat poor old Pemberton at Champion’s Hills, coming in on the right of Hovey who had the heaviest part of that fight. But it was a long time before we got into a place so hot as the thicket in front of Raymond, where we fought for the bank of the brook.

Henry O. Dwight

First Lieutenant and Adjutant 20th Ohio Veteran Volunteer Infantry

Lesson Plan

-

Henry O. Dwight, First Lieutenant and Adjutant 20th Ohio Veteran Volunteer Infantry. Photograph courtesy Ohio Historical Society. -

Map of Grant’s March. Map courtesy James L. Drake.

-

Union soldiers on the move during reenactment of the Battle of Raymond. Reenactment photo courtesy Rebecca Blackwell Drake. -

“The road lay through the very thickest kind of woods .....” wrote Dwight. Reenactment photo courtesy Rebecca Blackwell Drake. -

“At last we came to a little clearing .....” Reenactment photo courtesy Rebecca Blackwell Drake. -

Battle of Raymond reenactment at Waverly Plantation which was used as headquarters by Grant. Reenactment photo courtesy Rebecca Blackwell Drake. -

St. Mark's Episcopal Church in Raymond (built 1854) was used as a hospital for Union soldiers. Blood stains are still visible on its floors. Photo courtesy James L. Drake. -

Dwight wrote, “There was a big dinner in the town hall at Raymond which the ladies of the town had got ready to refresh the Johnnies on their return from the fight.” 1998 reenactment at the Hinds County Courthouse at Raymond of picnic hosted by the women of Raymond. Reenactment photo courtesy Rebecca Blackwell Drake.