The service of African Americans with the Confederate army during the American Civil War has long intrigued historians and Civil War buffs. Were these men soldiers or servants? Did they get shot? Why did they serve, and what was the nature of the relationship between Bblack servants and their White masters in uniform? The answers to these questions may never be completely understood, but one thing is clear from a variety of sources: African Americans were an integral part of the Confederate war effort.

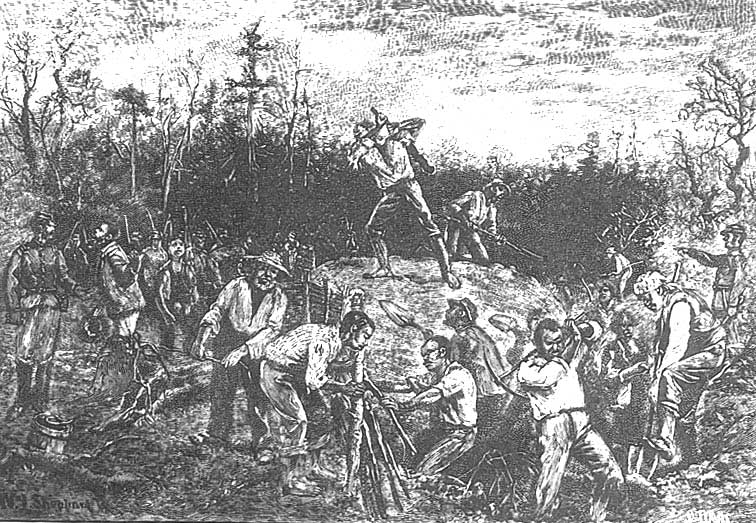

Black southerners contributed to the Confederate war effort in four ways. First, as enslaved people, they provided the labor that fueled the Southern cotton economy and maintained the production of foodstuffs and other commodities. Second, enslaved people were rented to or drafted by the Confederate government to work on specific projects related to the South’s military infrastructure, such as bridges and railroads. Third, Black southerners were part of the work force in the Confederacy’s war-related foundries, munitions factories, and mines. In addition, they transported food and war material to the front by wagon, and provided services to wounded and sick soldiers in Confederate hospitals. Last, a large number of Black southerners went to war with the Confederate army as noncombatants, serving as personal servants, company cooks, and grooms.

The lack of reliable information presents a problem with developing a better picture of what Black noncombatants did with the Confederate army. Documentation for the use of enslaved labor on fortifications and railroads is extensive because that type of labor was a matter of official policy and subject to contractual arrangements. The services of Black workers in Confederate arsenals, mines, and hospitals were also documented. Unfortunately, the same sort of documentation does not exist for Black noncombatants with the Confederate army because their service was not officially recognized. Consequently, the primary source of information regarding their service is anecdotal, and anecdotes do not provide a reliable basis for drawing historical conclusions. Anecdotes usually originate from a single source and thus lack corroboration. The shortcoming of anecdotes can be illustrated by the widely accepted – but inaccurate – generalization that most African Americans serving with the Confederate army were sent home after 1862.

Fortunately, there is another source of information about the service of these men. Although the information it provides is not as colorful as that found in the anecdotes recorded by Confederate veterans, it has the advantage of having been collected systematically and verified by witnesses. That source of information consists of their applications for Confederate pensions after the war.

Black Confederate pensioners

Veterans of the Union army who were disabled as a result of their service during the Civil War were eligible for a federal pension as early 1868. However, disabled Confederate veterans had to wait until their Confederate allies regained political control of the Southern states after Reconstruction to apply for pensions sponsored by the individual states. Although Confederate pensions were limited initially to disabled veterans, it was not long before eligibility was expanded to include veterans who were poor and in need. North Carolina and Florida led the way in 1885, and by 1898 all of the states that had seceded from the Union offered pensions to indigent Confederate veterans. Missouri and Kentucky followed suit in 1911 and 1912, respectively. These states, with the exception of Missouri, also extended coverage to indigent widows of veterans, as long as they did not remarry.

African Americans who had served with the Confederate army were not included – except in Mississippi, which had included African Americans in the state’s pension program from its beginning in 1888. It was not until 1921 that another state extended the eligibility for pensions to African Americans who had served as servants with the Confederate army. Unfortunately, Black southerners who applied for Confederate pensions in the 1920s were, for the most part, very old men. Consequently, the number of Black pensioners was small compared to the large number of Confederate veterans in the states that had allowed for pensions decades earlier. For example, Mississippi, which was the only state to include African Americans from its program’s beginning in 1888, had 1,739 Black pensioners; North Carolina, which first offered pensions in 1927 had 121; South Carolina, which first offered pensions in 1923, had 328; Tennessee, which first offered pensions in 1921, had 195; and Virginia, which first offered pensions in 1924, had 424 Black pensioners.

Initially, Mississippi’s pensions for Confederate veterans were limited to soldiers or sailors and their former servants with a disability sustained during the war, such as the loss of a limb, that prevented them from engaging in manual labor, and to women who had been widowed during the war and had not remarried. In 1892, Mississippi expanded the eligibility for pensions to include veterans, their former servants, and unmarried widows “who are now resident in this State, and who are indigent and not able to earn support by their own labor.”

Pension applications from African Americans in Mississippi were forwarded to the state auditor’s office by pension boards in each county. These applications are now on file in the Mississippi Department of Archives and History, where they are intermingled with applications from White soldiers and widows, all of which are filed alphabetically by last name. Black pensioners can be identified by the special application form that servants were required to use. A review of the applications for Confederate pensions in Mississippi – about 36,000 – reveals 1,739 applications from African Americans.

Pension applications

Pension applications for African Americans were different from those used for soldiers or widows. Questions on the applications for servants asked for the applicant’s name, age, the name of the person he had served during the Civil War, and the dates of his service. Questions also asked the unit to which the applicant’s master had been assigned. This information, coupled with his master’s name, allowed pension boards to verify the applicant’s service by checking Confederate muster rolls. This step in the approval process was crucial as contemporary records documenting the service of African Americans were nonexistent. There were no muster rolls for these men, most of whom had no last names at the time of their service.

Other Confederate states also wanted to know what Black applicants had done in regard to their service during the war, but they limited the applicant’s response to a single word or term, such as “body servant.” Interestingly, Mississippi did not start asking for this information until 1922, the same year it stopped asking for the applicant’s age.

Surprisingly, none of the states, except Mississippi, asked Black applicants if they were wounded as a result of their service with the Confederate army. This omission did not mean, however, that such information did not find its way onto application forms, for all states allowed the applicant to state why he should be awarded a pension, and applicants were not hesitant to report wounds received during the war. Nevertheless, information about wounds was not systematically obtained from Black applicants, except in Mississippi, and the county pension boards in Mississippi stopped collecting wound information in 1922.

Confederate pension programs were administered by the states, and all applications, including affidavits, were completed at the county level, even in those states where final approval rested with a state pension board. At least two witnesses, preferably former Confederate soldiers, were required to sign affidavits under oath attesting that the information provided by the applicant was accurate. As a result, applicants, White or Black, were usually known by the people who asked for the information on pension applications and affidavits. In contrast, the federal pension program for Union soldiers was administered centrally in Washington, D.C., where a small group of over-worked clerks attempted to sort through thousands of applications from all parts of the country, costing the federal government millions of dollars on fraudulent claims.

Black noncombatants

The proportion of Black pensioners among different work categories varied from state to state. The pension statutes in Mississippi, South Carolina, and Tennessee, for example, were intended primarily to reward the service of servants or cooks whose masters were assigned to units in the Confederate army. Despite state variations, an overall pattern of service among the Black pensioners is clear. On average, 85 percent of the Black pensioners served as servants or cooks with the Confederate army.

The number of Black pensioners in Mississippi was large enough to indicate the distribution of Black noncombatants within the Confederate army. Unit assignments can be identified for 1,312 Black applicants in Mississippi, of which nearly 1,100 were with units raised in the state. Unit assignments of masters (thus that of Black noncombatants) by percentage were: infantry, 57 percent; cavalry, 33 percent, artillery, 8 percent; and general staff, 2 percent). Of the seventy-nine infantry and cavalry regiments or battalions with Mississippi designations during the war, only three (4 percent) were not represented by at least one Black pensioner after the war.

As Black pensioners served in 96 percent of the regiments and battalions from Mississippi, it is evident that African Americans served with every army, in every theater, both early in the war and late. Furthermore, they were at every major battle of the Civil War east of the Mississippi River. When the end came, Black noncombatants with Mississippi units were at Appomattox and Bentonville, Mobile, and Selma.

The age at which Black noncombatants began serving with the Confederate army can be calculated from information contained on applications in Mississippi, Tennessee, and Virginia. The modal age (the age that occurs with the greatest frequency in the distribution) for all three states was seventeen. All of the states were remarkably similar when it came to the average length of time these Black noncombatants served with the Confederate army (2.6 years).

A central question about these men is whether some of them ever became soldiers. Unfortunately, applications submitted by Black pensioners do not address this question. By filling out a servant’s application, these men acknowledged at the onset that they were noncombatants, not soldiers. African Americans who may have enlisted as soldiers in the Confederate army, which would have entitled them to a larger pension, would have applied using a soldier’s pension form.

Although applications from Black pensioners provide relatively straightforward answers to questions that can be easily measured, such as wounds and their nature, they have serious limitations when it comes to dealing with personal feelings about their service. The question of the Black noncombatants’ motivation, for example, is only partially resolved by information from pension applications. Questions about motivation did not appear on application forms, and the vast majority of African Americans who labored for the Confederate war effort were enslaved. While it is true that many of the enslaved people who served as black noncombatants may have served willingly, how many – and how willingly – is a matter of speculation. Some Black southerners did volunteer.

The responses to questions on the nearly 3,000 applications from Confederate Black pensioners reinforce the conviction that Black noncombatants were an important part of the Confederate armies, and shed some light on what they did to support the Confederate war effort.

James G. Hollandsworth Jr., Ph.D., is a former professor of psychology and lecturer in history at the University of Southern Mississippi, and the author of “Looking for Bob: Black Confederate Pensioners After the Civil War,” which appeared in the winter 2007 edition of The Journal of Mississippi History, Vol. LXVIX, No. 4. and from which this article is condensed.

Selected bibliography:

Brewer, James H. The Confederate Negro: Virginia’s Craftsmen and Military Laborers, 1861-1865. Durham, N. C.: Duke University Press, 1969.

Gorman, Kathleen, “Confederate Pensions as Southern Social Welfare,” in Elna C. Green, ed., Before the New Deal: Social Welfare in the South, 1830-1930. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1999.

Franklin, John Hope. From Slavery to Freedom: A History of Negro Americans. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1980.

Mohr, Clarence L. “Bibliographical Essay: Southern Blacks in the Civil War: A Century of Historiography,” Journal of Negro History 59, April 1974, 177-95.

Oliver. John W. History of the Civil War Military Pensions, 1861-1885, Bulletin of the University of Wisconsin, no. 844. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin, 1917, 41.

Microfilm:

Mississippi Department of Archives and History, Confederate Pension Records

Website:

Confederate Pension Records (accessed April 2008)