In November 1966, Noel Henry, wife of prominent Clarksdale NAACP leader Aaron Henry, sent her regrets to Dorothy Height, president of the National Council of Negro Women (NCNW). Height was organizing a workshop to draw Black women leaders of all socioeconomic levels from around the state to Jackson to discuss how the NCNW could be most helpful to them. While Henry could not attend, she confirmed the value of bringing women, “regardless of status,” together. Furthermore, she emphasized that when this gathering of Black Mississippi women convened, “it can be said, ‘This is the voice of Negro women in Mississippi.’” The NCNW sought to strengthen the collective voice of Black women in Mississippi in the 1960s and 1970s. While some civil rights organizations like the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee had left the Magnolia State by the mid-1960s, NCNW instead dramatically increased its statewide membership and programming in the late 1960s and 1970s.

In 1935, The National Council of Negro Women was founded by educator and civil rights leader Mary McLeod Bethune to bring together twenty-nine national Black women’s organizations to speak as a collective lobbying voice. Bethune was a skilled politician who could appeal to supporters, both Black and White, of her work and activism. She worked for presidents Calvin Coolidge, Herbert Hoover, and Franklin Roosevelt, who appointed her director of the Division of Negro Affairs of the National Youth Administration from 1936 to 1942. As founder and president of the NCNW, Bethune not only fought for voting rights and desegregation but also insisted that Black women be included in leadership roles in government and private organizations. Although NCNW under Bethune and her successors did make some inroads in Mississippi in the late 1940s and early 1950s, it was under the fourth president, Dorothy Height, elected in 1957, that the Council developed a long-term presence in Mississippi.

Height was first called to the state in 1964 by Clarie Collins Harvey, a prominent Black Jackson businesswoman and organizational leader. Harvey and Height joined dozens of White and Black women in a secret inter-organizational meeting in Atlanta, Georgia. The women represented the Young Women’s Christian Association, the National Council of Jewish Women, the National Council of Catholic Women, and Churchwomen United, all prominent progressive women’s organizations of the era. Together these participants defied local segregation ordinances as they sat and ate together while discussing how they could be of better service to one another. At this meeting, Harvey stood up and asked the women to support the civil rights work that was already in place in Mississippi. Harvey, along with several others, had founded the Jackson-based women’s group Womanpower Unlimited, which worked in support of the Freedom Riders and civil rights activists by providing them food, housing, clothing, and other supplies.

Height and a White NCNW volunteer, Polly Cowan, heeded her call and created the organization Wednesdays in Mississippi (WIMS) to bring elite Black and White women from northern and western cities to Mississippi during Freedom Summer. Over the summer, forty-eight women, two-thirds White and one-third Black, flew into Jackson on Tuesday, visited a smaller Mississippi town, such as Hattiesburg, Canton, Meridian, Vicksburg, and Ruleville on Wednesday, and then returned home on Thursday. Although WIMS drew women from progressive Black and White women’s clubs, the NCNW was the only Black organization among the major sponsors. It was also the only group that publicly sponsored WIMS. WIMS women met with White and Black Mississippi women of their respective national organizations in hopes that they could strengthen support for local civil rights work. They also hoped to convince White women to become more supportive of Council of Federated Organizations (COFO) civil rights activities.

Though WIMS was unable to build much support among southern White women, it did strengthen links between northern and southern civil rights workers. Women from WIMS supported Harvey’s group Womanpower Unlimited; Mississippians for Public Education, an organization of progressive White women who sought to keep the public schools open in the face of desegregation; and the Freedom School and voter registration projects of COFO and the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party. WIMS participant Ruth Batson – a Boston school desegregation activist, education chairman of the Massachusetts NAACP, and a delegate to the 1964 Democratic National Convention – was skeptical of the WIMS project at first, but later saw its value. She was so impressed by the civil rights work that she witnessed while visiting Mississippi, especially that of George Raymond and Annie Devine of Canton, that she pushed the Massachusetts delegation to the Democratic National Convention (DNC) to strengthen their support for the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party’s challenge to unseat the all-White DNC delegation from Mississippi.

The following summer, nearly fifty more WIMS women traveled to Mississippi to serve as volunteers for Head Start projects around the state. Six WIMS women and four prominent NCNW women, including Height, also participated in an institute on desegregation in the secondary school classroom, sponsored by Dr. Roscoe Boyer in the University of Mississippi School of Education. For most in the predominantly-White group of over one hundred teachers and principals, it was their first time interacting with Black educators in any significant way, and they were very impressed with Height and the others.

In May 1966, the NCNW became tax-exempt as it achieved 501(c)(3) status, which helped it win federal and private foundation grants to fund self-help projects in Mississippi. From November 1966 through July 1967, the NCNW ran three workshops (the first was mentioned at the beginning of this essay) to bring together Mississippi women to discuss how the NCNW could help them. Wednesdays in Mississippi renamed itself Workshops in Mississippi to mark this transition. These workshops brought together Black women from all over the state, including civil rights leaders such as Fannie Lou Hamer, Unita Blackwell, Annie Devine, and Jeanette Smith. Height and other staff helped participants write War on Poverty grant applications for projects that included a school breakfast program in Canton, a childcare center in Ruleville, and a home for unwed mothers in Okolona. All three projects were implemented in some form within a few years. Through these workshops, the NCNW also strengthened its respect for local leadership, especially that of Hamer and Blackwell, whom it hired as staff. For its first twenty years, the NCNW relied mostly on volunteers and had very few paid staff. After acquiring tax-exempt status, the NCNW was able to hire workers. By 1975, they had sixty regular employees and forty-one additional staff working in one of its poverty projects. In 1975, one-fourth of these staff members were from Mississippi.

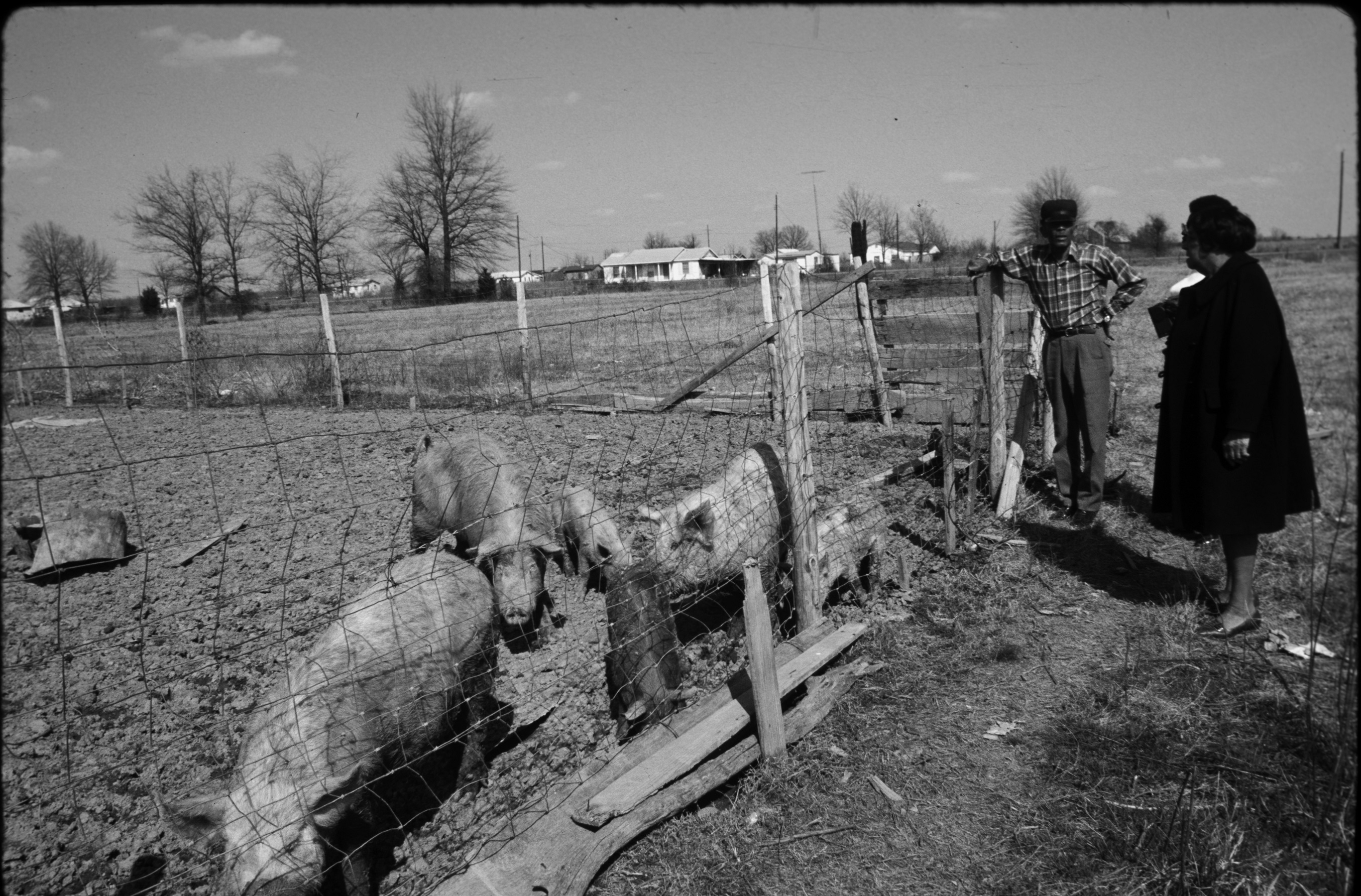

After the workshops of 1966–67, women in the NCNW established poverty projects around the state, including purchasing the pigs for Fannie Lou Hamer’s pig bank in her Freedom Farm. In 1968, the Council purchased fifty sows and five boars, which grew to over three thousand pigs by 1973. The NCNW also bought fencing and seeds for the pig farm and donated soil tillers, a tractor, a storage house, and a freezer for other community farms. That same year, NCNW built a low-income home ownership neighborhood of two hundred single-family homes in Forest Heights in Gulfport. The neighborhood contained three-, four-, and five-bedroom brick homes.

The NCNW’s growing number of projects in Mississippi also helped strengthen its organizational presence in the state. While the NCNW had some activity in Mississippi in the late 1940s and early 1950s, there was no Council presence in the state by the early 1960s. Impressed with the work that the NCNW began to develop in Mississippi, the women of Womanpower Unlimited decided to become a part of NCNW after disbanding their organization in 1968. Jessie Mosley, a founder of Womanpower Unlimited and longtime historian of the Black experience in Mississippi, helped to establish sections of the NCNW around the state. As the first NCNW state convener, Mosley helped build the number of NCNW sections from zero in 1964, when WIMS first arrived, to twenty-seven by 1973. Thanks to the groundbreaking work of NCNW in the 1960s and 1970s, the organization continues to thrive as it offers vital programs to promote health, education, voting, financial literacy, and Black pride in communities around Mississippi.

Rebecca Tuuri is an associate professor of history at the University of Southern Mississippi. This article is adapted from her book Strategic Sisterhood: The National Council of Negro Women in the Black Freedom Struggle, which won the 2019 Julia Cherry Spruill prize for best book published in 2018 on southern women’s history. Used by permission of the publisher, UNC Press.

Lesson Plan

-

The closing dinner marking the retirement of Mary McLeod Bethune in November 1949. In the center of the photograph is Bethune. On the far right of the photograph is Dorothy Height, who served as NCNW president from 1957 to 1998 and helped boost its presence and activism in Mississippi. Photograph by Fred Harris, courtesy of the Mary McLeod Bethune Council House National Historic Site. -

1964 Wednesdays in Mississippi Team #3 from the Washington, D.C. area. Photograph courtesy of the Mary McLeod Bethune Council House National Historic Site.

-

Left to right: Fannie Lou Hamer, Dorothy Height, and Polly Cowan at the 32nd NCNW annual convention, November 1967. Photograph courtesy of the Mary McLeod Bethune Council House National Historic Site. -

NCNW representatives visiting a pig bank site in the Mississippi Delta. Photograph courtesy of the Mary McLeod Bethune Council House National Historic Site.

Sources and Suggested Reading

Mrs. Aaron Henry to Mrs. [Dorothy] Height, November 13, 1966, Series 19, Folder 221, NCNW Papers, National Archives for Black Women’s History, Washington, D.C., as cited in Tuuri, Strategic Sisterhood: The National Council of Negro Women in the Black Freedom Struggle (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2018), 109.

For more on Bethune as politician, see Bettye Collier Thomas, N.C.N.W., 1935-1980, Washington, D.C.: National Council of Negro Women, 1981

Deborah Gray White, Too Heavy a Load: Black Women in Defense of Themselves, 1894–1994 (New York: W.W. Norton, 1999)

Audrey Thomas McCluskey and Elaine Smith, Mary McLeod Bethune: Building a Better World, Essays and Selected Documents (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1999)

Audrey Thomas McCluskey, “Multiple Consciousness in the Leadership of Mary McLeod Bethune,” NWSA Journal 6, no. 1 (Spring 1994): 68–81

Joyce A. Hanson, Mary McLeod Bethune and Black Women’s Political Activism (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2003).