William Faulkner, Mississippi’s most famous novelist, once said, “To understand the world, you have to understand a place like Mississippi.”

To the world, Mississippi was the epicenter of the cotton production phenomenon during the first half of the nineteenth century. The state was swept along by the global economic force created by its cotton production, the demand by cotton textile manufacturing in Europe, and New York’s financial and commercial dealings. Mississippi did not exist in a vacuum. So, in a sense, Faulkner’s words could be reversed: “To understand Mississippi, you have to understand the world.”

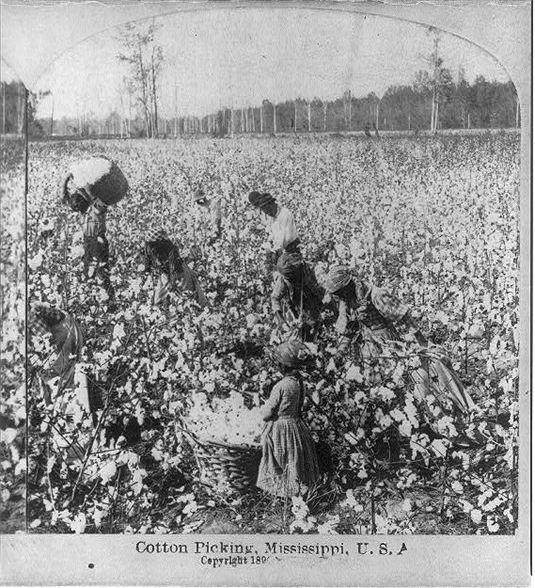

Mississippi’s social and economic histories in early statehood were driven by cotton and slave labor, and the two became intertwined in America. Cotton was a labor-intensive business, and the large number of workers required to grow and harvest cotton came from slave labor until the end of the American Civil War. Cotton was dependent on slavery and slavery was, to a large extent, dependent on cotton. After emancipation, African Americans were still identified with cotton production.

The slavery compromise

This particular chapter of the story of slavery in the United States starts at the Constitutional Convention of 1787 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. When the delegates wrote and agreed upon the Constitution, cotton production was virtually nonexistent in America. The enslaved population in the United States was approximately 700,000 at the time of the signing of the Constitution. The slave states of South Carolina and Georgia were adamant about having slavery protected by the Constitution. Connecticut’s Roger Sherman, one of the delegates who brokered the slavery compromise, assumed that the evil of slavery was “dying out … and would by degrees disappear.” He also thought that it was best to let the individual states decide about the legality of slavery. Thus, the delegates faced the question: should there be a United States with slavery, or no United States without slavery? The delegates chose a union with slavery.

Soon after the signing of the Constitution, cotton unexpectedly intervened in the 1790s and changed the course of America’s economic and racial future because of the simultaneous occurrence of two events: the mass production of textiles and the mass production of cotton. In the late 18th century, the process started in Great Britain where several inventions — the spinning jenny, Crompton’s spinning mule, and Cartwright’s power loom — revolutionized the textile industry. The improvements allowed cotton fabrics to be mass produced and, therefore, affordable to millions of people.

The cotton gin

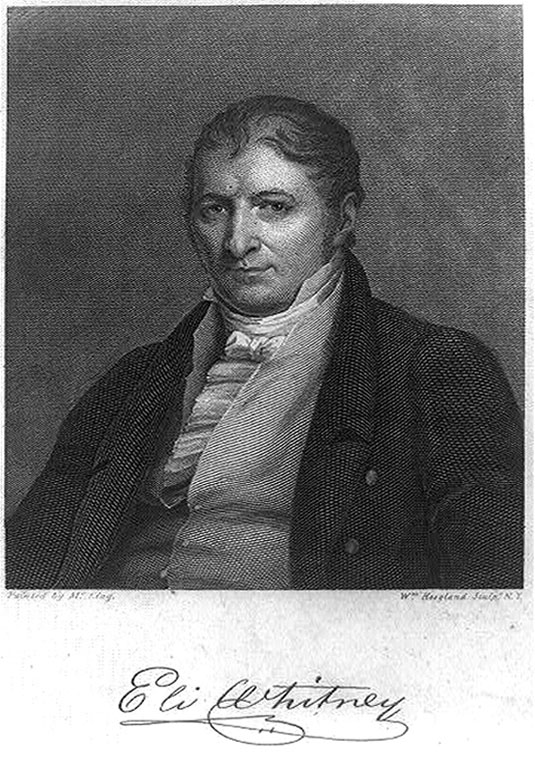

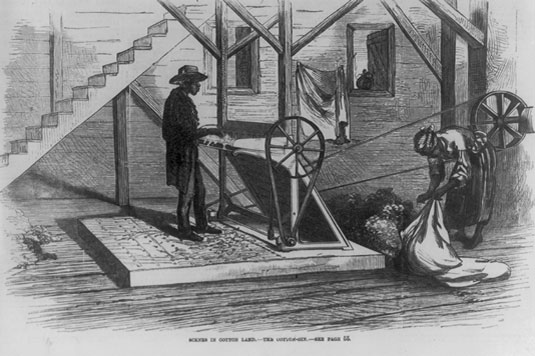

At the same time, Eli Whitney, a twenty-eight-year-old unemployed recent graduate of Yale University, journeyed to the South to become a tutor on a plantation. He soon became obsessed with the bottleneck in cotton production on his employer’s Georgia plantation. In 1793, the fledgling mechanic soon found a solution to the problem of cleaning cotton and the separation of the seed from the fiber. After a few months, he wrote the now-famous letter to his father in which he described his discovery: “I involuntarily happened to be thinking on the subject [of cleaning cotton] and struck out a plan of a Machine [to remove the cotton seed]…I concluded to relinquish my school and turn my attention to perfecting the Machine.” That machine was the cotton gin.

Whitney gave up his career as a teacher to devote full time to manufacturing cotton gins and making money. Sadly for Whitney, the cotton gin generated no profits because other manufacturers copied his design without paying him fees. He had obtained a patent on the cotton gin but it proved to be unenforceable. Whitney’s priorities, henceforth, were money and manufacturing. Whitney never seemed, as one historian noted, to care about slavery “one way or the other.”

Demand for cotton

Whitney is given credit for unleashing the explosion of American cotton production which was, in turn, propelled by the seemingly insatiable appetite for cotton from the British cotton textile mills. A quick glance at the numbers shows what happened. American cotton production soared from 156,000 bales in 1800 to more than 4,000,000 bales in 1860 (a bale is a compressed bundle of cotton weighing between 400 and 500 pounds). This astonishing increase in supply did not cause a long-term decrease in the price of cotton. The cotton boom, however, was the main cause of the increased demand for enslaved labor – the number of enslaved individuals in America grew from 700,000 in 1790 to 4,000,000 in 1860. Americans were well aware of the fact that the economic value placed on an enslaved person generally correlated to the price of cotton. Thus, the cotton economy controlled the destiny of enslaved Africans.

By 1860, Great Britain, the world’s most powerful country, had become the birthplace of the industrial revolution, and a significant part of that nation’s industry was cotton textiles. Nearly 4,000,000 of Britain’s total population of 21,000,000 were dependent on cotton textile manufacturing. Nearly forty percent of Britain’s exports were cotton textiles. Seventy-five percent of the cotton that supplied Britain’s cotton mills came from the American South, and the labor that produced that cotton came from the enslaved.

Because of British demand, cotton was vital to the American economy. The Nobel Prize-winning economist, Douglass C. North, stated that cotton “was the most important proximate cause of expansion” in the 19th century American economy. Cotton accounted for over half of all American exports during the first half of the 19th century. The cotton market supported America’s ability to borrow money from abroad. It also fostered an enormous domestic trade in agricultural products from the West and manufactured goods from the East. In short, cotton helped tie the country together.

Cotton and population

From the time of its gaining statehood in 1817 to 1860, Mississippi became the most dynamic and largest cotton-producing state in America. The population and cotton production statistics tell a simple, but significant story. The growth of Mississippi’s population before its admission to statehood and afterwards is distinctly correlated to the rise of cotton production. The White population grew from 5,179 in 1800 to 353,901 in 1860; the enslaved population correspondingly expanded from 3,489 to 436,631. Cotton production in Mississippi exploded from nothing in 1800 to 535.1 million pounds in 1859; Alabama ranked second with 440.5 million pounds.

MISSISSIPPI POPULATION

| White | “Free Colored” | Slave | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1800* | 5,179 | 182 | 3,489 | 8,850 |

| 1810* | 23,024 | 240 | 17,088 | 40,352 |

| 1830 | 70,443 | 519 | 65,659 | 136,621 |

| 1840 | 179,074 | 1,366 | 195,211 | 375,651 |

| 1850 | 295,718 | 930 | 309,878 | 606,526 |

| 1860 | 353,901 | 773 | 436,631 | 791,305 |

MISSISSIPPI COTTON PRODUCTION

| (millions of pounds) | |

|---|---|

| 1800 | 0 |

| 1833 | 70 |

| 1839 | 193.2 |

| 1849 | 194 |

| 1859 | 535.1 |

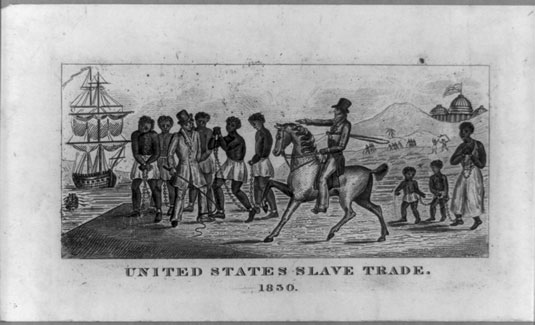

Mississippi and its neighbors – Alabama, western Georgia, Louisiana, Arkansas, and Texas – provided the cheap land that was suitable for cotton production. Cotton provoked a “gold rush” by attracting thousands of White men from the North and from older slave states along the Atlantic coast who came to make a quick fortune. Enslaved people were transported in a massive forced migration over land and by sea from the older slave states to the newer cotton states. In 1850, twenty-five percent of the population of New Orleans, Louisiana, was from the North and ten percent of the population in Mobile, Alabama, was former New Yorkers.

Mississippi attracted investors as well as residents. Auctions of cheap Indian lands as a result of cessions of land by the Choctaw and Chickasaw nations drew bidders from the South and East. For example, in the 1830s, the largest purchasers of Chickasaw land in Mississippi were the American Land Company and the New York Land Company. The two companies represented investors or speculators from New York, Boston, and other New Englanders.

New York City, not just Southern cities, was essential to the cotton world. By 1860, New York had become the capital of the South because of its dominant role in the cotton trade. New York rose to its preeminent position as the commercial and financial center of America because of cotton. It has been estimated that New York received forty percent of all cotton revenues since the city supplied insurance, shipping, and financing services and New York merchants sold goods to Southern planters. The trade with the South, which has been estimated at $200,000,000 annually, was an impressive sum at the time.

Complicity of White America

Most New Yorkers did not care that the cotton was produced by enslaved people because for them it became sanitized once it left the plantation. New Yorkers even dominated a booming slave trade in the 1850s. Although the importation of enslaved Africans into the United States had been prohibited in 1808, the temptation of the astronomical profits of the international slave trade was too strong for many New Yorkers. New York investors financed New York-based slave ships that sailed to West Africa to pick up African captives that were then sold in Cuba and Brazil.

In addition to dominating the slave trade, New York denied voting rights to its small free Black population, which comprised only one percent of the population. New York accomplished this by imposing property ownership requirements for its free Black residents, while White New Yorkers had no such restriction. New York's poor Black population was effectively disfranchised. In 1857, seventy-five percent of Connecticut voters elected to deny suffrage to African Americans, and even after the Civil War, voters there again denied Black male residents the right to vote. Some western states, such as Indiana, Ohio, and Illinois, tried to exclude African Americans at the same time they were aggressively recruiting millions of White European immigrants. White America, not just White southerners, helped determine that the destiny of Black America would be in the cotton fields of the South for many decades to come.

On the eve of the Civil War, cotton provided the economic underpinnings of the Southern economy. Cotton gave the South power — both real and imagined. Cotton dictated the South’s huge role in a global economy that included Europe, New York, other New England states, and the American west. This economic growth exacted a severe and tragic human price through slavery and the prejudicial treatment of free Black people.

Mississippi was, therefore, both a captive of the cotton world and a major player in the 19th century global economy.

Eugene R. Dattel, a Mississippi native and economic historian, is a former international investment banker. His first book, The Sun That Never Rose, predicted Japan's economic stagnation in the 1990s. His next book, Cotton and Race in America (1787-1930): The Human Price of Economic Growth, will be published in 2007.

-

Cotton pickers in Mississippi, mid-1800s. Courtesy of the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, LC-USZ62-49307. -

A close view of a stalk of cotton. Photograph courtesy of Mississippi Department of Archives and History, PI/1997.0006.0470.

-

Eli Whitney (1765-1825) Courtesy of the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, LC-USZ62-8283. -

The cotton gin. Courtesy of the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, LC-USZ62-37836. -

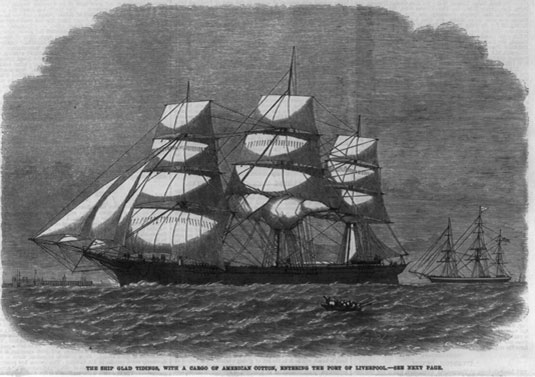

The ship, Glad Tidings, with a cargo of American cotton entering the port of Liverpool in the mid-1800s. Print from The Illustrated London News courtesy of the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, LC-USZ62-64405. -

An abolitionist print shows a group of slaves in chains being sold by a trader on horseback to another dealer. The U.S. Capitol with the American flag is in the distance. Courtesy of the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, LC-USZ62-89701.

References:

Albion, Robert Greenhalgh. The Rise of New York Port, 1815-1860. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1970

Bowen, Catherine Drinker. Miracle at Philadelphia: The Story of the Constitutional Convention May to September 1787. Boston: Little Brown, 1986

Bruchey, Stuart. Cotton and the Growth of the American Economy: 1790-1860. New York: Random House, 1967

Foner, Philip Sheldon. Business & Slavery: The New York Merchants & the Irrepressible Conflict. New York: Russell & Russell, Publishers, 1968

Green, Fletcher Melvin. The Role of the Yankee in the Old South. Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 1972

Hughes, Jonathan. The Vital Few: The Entrepreneur & American Economic Progress. New York: Oxford University Press, USA, 1986

North, Douglass C. Economic Growth of the United States: 1790-1860. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1966

Young, Mary Elizabeth. Redskins Ruffleshirts and Rednecks: Indian Allotments in Alabama and Mississippi, 1830-1860. Norman, OK:

University of Oklahoma, 2002