Today, legal and institutionally supported racial segregation within places of higher learning feels like a thing of the past. Yet, integration and increased representation of students of color, especially Black students, did not come easily in the Mississippi Delta even after racial segregation was outlawed. On the federal level, the Supreme Court ruled that segregation within public schools was unconstitutional through the 1954 case, Brown vs. Board of Education of Topeka.

Movements to desegregate public schools took place across the South. White leadership in many places resisted integration with the aid of local law enforcement and even state support. For example, Arkansas Governor Orval Faubus used the National Guard to block entry for the “Little Rock Nine” attempting to integrate Central High School. In Mississippi, Clyde Kennard, an African American veteran from Hattiesburg, was barred from enrolling in Mississippi Southern College in the late 1950s. As a result of his efforts, he was later falsely accused and convicted of minor crimes and sent to Parchman Prison. In 1962, the federal court ordered the University of Mississippi to admit its first Black student, James Meredith, resulting in mob violence and federal intervention.

While many Mississippians know the story of James Meredith, less is known about the Black Campus Movement at smaller, public regional colleges and universities across the South, such as Delta State University, located in the Mississippi Delta town of Cleveland. In this article, we recount this history at Delta State College (as it was known until 1974), drawing from publicly available archives and oral histories with former students who participated in the 1969 sit-ins and faculty, past and present, conducted by students from 2019 to 2021.

Integration and Anti-Black Racism at DSC

Although racial segregation in public schools was declared unconstitutional in 1954, Delta State did not admit its first Black student, Shirley Antoinette Washington, until 1967. Integration was met with resistance and public opposition, and the relationships among Black students and White students and faculty remained tense. There were no Black professors or counselors at the time, and the only Black people students saw worked as custodians, groundskeepers, and laundry attendants.

Although there were a few “good” White people on campus, former Black students recall mistreatment by faculty and students alike ranging from being automatically placed in remedial classes, called the “n-word,” living in segregated dorms, and physical harassment or avoidance by most White students. The Black students got especially tired of mistreatment by faculty who were supposed to be teaching them. For example, Maggie Crawford recalls being passed over by a White instructor who later assumed she was cheating. In spite of all of this, Black students built a small community who took care of one another. Muriel Lucas comments on this relationship:

There was a small group of us on campus, and I can’t really tell you how many there were, but immediately those of us who lived on campus, we were together, because there was safety in numbers. And I can remember some of the men saying to us, “Don’t go anywhere on this campus alone, if at 8:00 or 9:00 at night you need to go to the library, you call us first. Don’t go out walking on this campus by yourself.” And I just never did it. But when I think back on the offer, these were men, most of them, I think, were there when I got there. And they were protective, they were loving, and they were respectful. I always felt safe with them.

With growing visibility, Black students had to keep each other safe. Unrest grew among a group of Black students on campus, in sync with the larger Black student movement across the state and the country.

The Cafeteria Fight, aka the Straw that Broke the Camel’s Back

Although Delta State was legally integrated, White students made simple movement on campus difficult for Black students. Going to the cafeteria became one of the most difficult activities as a semi-social space without much faculty supervision. As one student put it, there was an “unspoken rule” that the cafeteria remain segregated. Therefore, according to Murial Lucas, Black students timed their trips to go together and to sit at the same table. Oral history participants remember the cafeteria as the site of numerous standoffs between White and Black students. The death of a Black student named James Kennedy was the “straw that broke the camel’s back” according to Maggie Crawford. During a cafeteria fight between Black and White students, a White student struck Kennedy who reportedly had a seizure during the incident. Crawford recalls that Kennedy never fully recovered and eventually died. Kennedy’s death alongside other incidents of discrimination led fifty-one Black students, and one White student, to decide, in Crawford’s words, “Enough is enough!”

Leading up to the Sit-In

Across Mississippi and the country, Black students organized at universities in the Black Campus Movement from 1965 to 1972. According to historian Ibram Rogers, students were motivated by the assassination of Malcolm X in 1965 and the Watts rebellion months later.

Organizing activities took place at historically Black institutions such as Tuskegee University, Howard University, Southern University, Mississippi Valley State University, and Jackson State University, just to name a few.

Many of the African Americans at Delta State witnessed or knew students at other universities who organized around Black student demands. In the weeks leading up to the Delta State sit-in, Black students formed the Black Student Organization (BSO) in 1969. Vietnam veteran Beverly Perkins became the president, inspired by the disconnect he felt in fighting for his country only to return to racism at home. Through the BSO, Black students were able to document all their individual experiences of discrimination on campus and build relationships to one another. The Wesley Foundation, a Methodist student ministry located near campus, became a meeting place for students to congregate (Yvonne Stanford, Jennifer Buckner).

At Delta State, the sit-in was the result of planning and preparation, and students often worked with civil rights leaders from the surrounding community, such as Fannie Lou Hamer, Amzie Moore, and Owen Brooks. BSO member Donald Sutton was the liaison between Brooks and Beverly Perkins, so Sutton was often assumed by outsiders to be the lead agitator.

The leaders of the BSO wrote a document entitled “Black Student Demands,” which began with a simple letter expressing concern around the treatment of Black students and the need for “proportionate participation” for the “well being of Black students.” Following the letter were ten demands for a Black counselor, Black instructors, the end of derogatory language regarding Black students, fairness in grading, fairness in determining campus access, scholarships, Black history and books in the library, and Black representation within student government.

The BSO presented Delta State’s president, James Ewing, with these demands on February 27, 1969, giving him a week to respond. The students clearly stated their intentions to continue exerting pressure on the Delta State administration if their goals were not met, not as a threat to the administration, but “to convey [their] feelings in a sincere and straightforward manner.” In other words, they made their demands known clearly and succinctly and were prepared to act if the administration failed to meet their demands. After the week passed, Black students held an open meeting at 10 a.m. on Thursday March 6, 1969. According to Ed Williams, about seventy students attended the meeting to prepare a response to the administration’s dismissal of their demands.

After the meeting, the students made their way to Kethley Hall, the administration building on campus, to reiterate their demands. Around 12:30 p.m., the students sat alongside the walls outside of President Ewing’s office to bring attention to their cause. Muriel McCraney recalls siting peacefully without blocking access to the building nor the hallway. Her remembrance was corroborated by William Pennington, who was an instructor in philosophy at Delta State College. William Pennington in his recollection stated, “As I walked inside I saw all the students sitting against the walls on either side of the hallway with their feet sticking out onto the floor.” He would be called later to testify on behalf of the sit-in protestors. (Tapestry 2005, pp. 55-61)

March 10, 1969—The Sit In

Disregarded by Ewing, the group of Black students, led by the Black Student Organization, realized that in order to get action, they had to take matters into their own hands. On March 10, 1969, they met in the Union at noon. Next, they marched on campus singing freedom songs, chanting, and carrying signs. Muriel Lucas, Talmadge Davis, and Maggie Crawford recall leaving the Union to go to President Ewing’s home. They sat on his lawn, singing and chanting, but when they realized he was not home, they headed for Kethley Hall. The BSO led the march, but many Black students were accidentally caught up in the action. While the BSO planned and organized around the demands, there are mixed recollections as to whether the actual sit-in was planned or more spontaneous, an outcome of the momentum and excitement the students felt. According to Yvonne Stanford, once they got to Kethley, the students were told that the police would be called if they did not leave. They remember President Ewing coming out and asking them to disperse. Muriel Lucas recalls the group telling Ewing’s secretary, “We’re not going until he’ll talk to us at least. Just talk to us.” When Ewing refused to address their demands, the students remained.

James Powers, a sympathetic White student and Student Government Association president at the time, remembers asking, “Who’s the leader here?” and the students responded, “We have no leaders. We’re all leaders.” This statement was also confirmed in Miss Delta, the student publication at the time (March 17, 1969). After several refusals to leave the building, the administration called the police, who confronted the students and took them outside. They were placed under arrest for disrupting the classes at the college by Mississippi state highway patrolmen armed with bully sticks, riot gear, shields, and helmets. Some students remembered police dogs. This was an eye opening experience for these students. Lucas remembers one sympathetic White student who said, “If you take them, you have to take me too.” Other White students applauded the efforts and tactics of the administration. Lucas recounts what happened next:

And so when I stepped out of the Kethley building, as we stepped out the door facing Highway 8 of Sunflower Road, a crowd had gathered. But there were national guardsmen, there were policemen, they had on riot gear, they had on gas masks, they had guns in their hands. And I thought, “God, they’re ready to kill us.” And I’ve always thought that had we not been on a White campus they probably would have, but they didn’t. We were put on the bus, taken to Parchman.

Many students jokingly recall that they were put on a black bus. Former BSO member Lula Jones remembers that half hour bus ride to the infamous Parchman Prison. She worried, “Where are they taking us? Are they going to take us all out and hang us?” When they arrived at Parchman, the reluctant warden temporarily housed the students on Death Row. He gave them playing cards and allowed them to sing and congregate with each other. They sang freedom songs until other inmates yelled for them to quiet down.

After Parchman

After one night in Parchman, the students were released through the support of the Black community in Cleveland. Owen Brooks made sure the students’ parents did not bond them out with money, but instead used property bonds (Maggie Crawford, Muriel Lucas). Muriel Lucas recalls the support of the community when the students returned to Cleveland and found the courtroom full of Black people.

The yard, the house in the courtroom full of Black people, in their maid dresses, in their work clothes, in their farm clothes, it was full of Black people. That’s what I remember. And they came, many of them with paper in their hand. They were going to put up their houses to make sure that we got out of jail. To this day, they didn’t know us. But they were determined that they would do everything they could to make sure that we didn’t spend another night in jail. I grew up that night.

After students were bonded out, they had to face individual hearings on campus. Don Sutton, the presumed leader of the sit-in, was especially targeted. Although individual acts of discrimination continued on campus, former students remember their grades were equitably calculated and faculty no longer called them the “n-word” in class. Delta State did eventually hire more Black faculty and staff. It is difficult to determine how many of the other demands were met, but the university never created a Black history course, nor were Black history books intentionally added to the library or curriculum.

The current generation can take inspiration from the struggles of the 1969 BSO Sit-in to enact change in their own communities. Today, students at Delta State University benefit from the efforts of these courageous young Black students. More than fifty years later their actions serve as an inspiration for those seeking justice, peace, and equity.

Arlene Sanders retired as an instructor of political science at Delta State University. Carrie Freshour teaches geography at the University of Washington, but was previously at Delta State. Sykina Butts is a multimedia journalist at Delta News and a 2019 graduate of Delta State. All three are associate producers of the documentary, Voices From the Sit-in.

Lesson Plan

-

Kethley Hall protestors (l to r) Lela Westbrook, Joyce Dugan, Don Jacobs, Jerome Lyles, James Williams, and Martha Grayer. Courtesy of Delta State University Archives and Museums. -

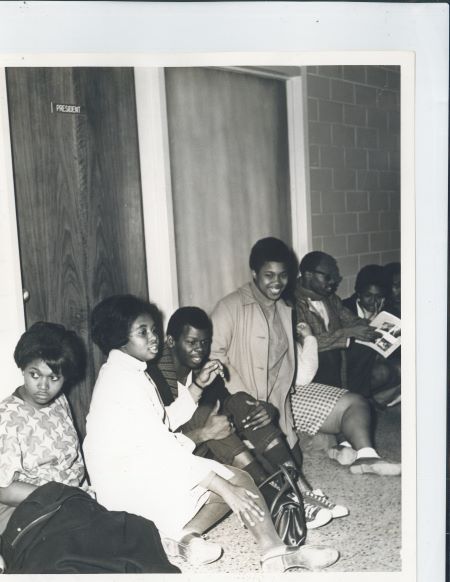

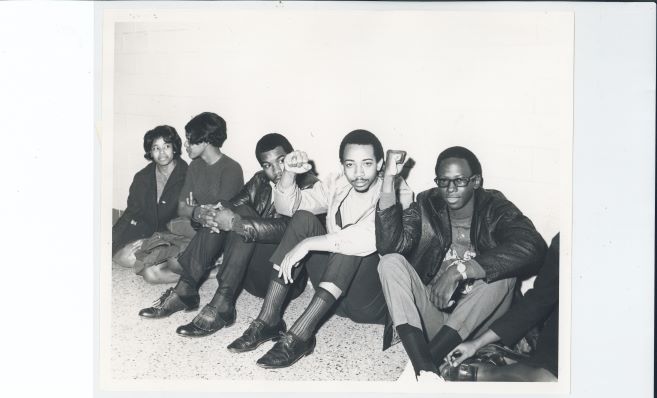

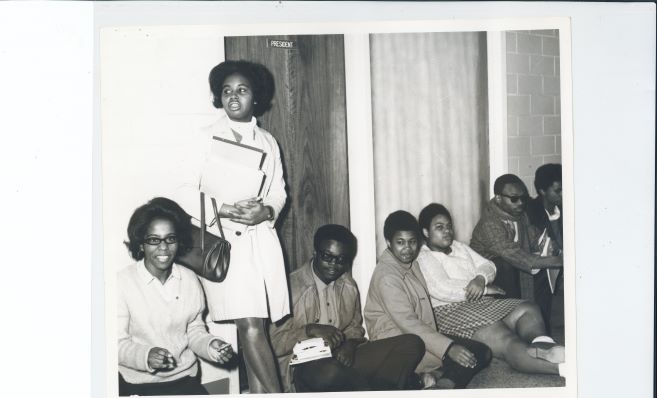

Kethley Hall protestors on March 10, 1969 at Delta State College. Courtesy of Delta State University Archives and Museums.

-

Kethley Hall protestors (l to r) Lela Westbrook, Mary Louis, Lee Greene, Vertis Johnson, George Watts, and Effie Sledge. Courtesy of Delta State University Archives and Museums. -

Kethley Hall protestors (l to r) Pearlie White, Sharon Burnett, Roy Allen, Willie Cherry, and Talmadge Davis. Courtesy of Delta State University Archives and Museums. -

Kethley Hall protestors (l to r) Maggie Daily, Joyce Dugan, Sonny Garner, Jerome Lyles, Jennifer Buckner, James Williams, and Martha Grayer. Courtesy of Delta State University Archives and Museums. -

Students protest on the lawn of the college president. Courtesy of Delta State University Archives and Museums. -

Students protest on the lawn of the college president. Courtesy of Delta State University Archives and Museums. -

Thomas Freeman and Luther Thomas march in protest. Courtesy of Delta State University Archives and Museums. -

Barbara McClinton and a fellow student march at the home of the college president. Courtesy of Delta State University Archives and Museums. -

Parchman Prison, about a half hour drive northeast of Cleveland.

Sources:

Oral interviews with Maggie Crawford, Yvonne Stanford, Talmadge Davis, Muriel Lucas, Lula Jones, and Vertis Johnson