Eudora Welty is one of America’s greatest writers. When she died in 2001, she left a substantial body of prose — fiction and non-fiction. Literary critics believe her work will become a more and more enduring fixture of the American literary canon, as scholars and readers continue to explore her works in order to understand them better.

Welty’s complex body of work explores the interiors of family structures. She explores both the relationships between husband and wife and those between parents and children, in particular those relationships between mothers and daughters. She has written with precision and insight about these delicate though monumentally important structures. Welty goes to the very marrow of our lives — to the deepest most intimate places where we live the most intimate parts of our daily lives. At the same time, her work responds in numerous ways to the more public issues of Mississippi’s social and historical landscape.

The young writer

She was born April 13, 1909, in Jackson, Mississippi. Except for lots of travel in Europe and in the United States, including an extended stay in San Francisco during the 1940s, she lived in Jackson her entire life, becoming, as she told Katherine Anne Porter, “underfoot locally” — a humorous phrase by which she described a fairly active social life and an involvement in community affairs.

She spent her first two years of college at Mississippi State College for Women in Columbus, then transferred for her final two years to the University of Wisconsin at Madison. She did graduate study in New York City at Columbia University, but returned to Jackson for good in 1931 at the death of her father.

Welty had already begun writing even as a little girl. At age eleven, for example, in 1920, she published a poem in the children’s magazine St. Nicholas. She continued to write for student newspapers. At home at the beginning of the Great Depression, she worked for a Jackson radio station and wrote a Jackson society column for the Memphis, Tennessee, Commercial Appeal.

The photographer

She had for some time been interested in photography, and in 1935 she took a job with the Works Progress Administration, which had her traveling throughout Mississippi taking photographs of conditions during the depression. She maintained throughout her life that her experiences during these months of WPA employment were invaluable to her writing and publishing career.

She took hundreds of photographs of depression Mississippi, some of which were published to almost universal acclaim in One Time, One Place (1971) and Photographs (1989). More importantly, perhaps, during her employment with the WPA, Welty gained a knowledge of Mississippi’s backroads, its people, and its fabulous history. That knowledge nourished her imagination and supplied her with numerous settings for her works.

Welty’s landscape

She set many of her early stories in Natchez and the surrounding area, including some of her more famous ones, like “A Worn Path” and “Old Mr. Marblehall.” Her second book, The Wide Net (1943), uses the Natchez Trace as a narrative backbone that gives structure to a collection of stories occurring from Natchez’s earliest history to the most recent times all up and down the trace. Two stories in particular address themselves to the colorful history of the Natchez region: “First Love” retells the story of Aaron Burr’s romantic escape into Mississippi through the eyes of a deaf boy, and “A Still Moment,” also in The Wide Net, lyrically tells the story of a chance encounter — which never happened! — between the naturalist John James Audubon, the evangelist Lorenzo Dow, and the Natchez Trace criminal James Murrell. Her first novel, The Robber Bridegroom (1942), likewise set on and around the Natchez Trace and the Mississippi River, involves the legendary Mississippi River raftsman Mink Fink.

Welty also set fiction in the Mississippi Delta — the novel Delta Wedding (1946) and the story “Powerhouse” — and a novel in the northeast Mississippi hills: her best-selling Losing Battles (1970). Thus Mississippi, both its geography and its history, is a powerful presence throughout her fiction. And so, inevitably, is its politics.

Although Welty was not a crusader in the cause of civil rights during the 1960s (and took a lot of heat from critics because she seemed to be staying quiet during the early years of the movement), she wrote very powerful indictments of racism in two stories of that period. The first story, “Where is the Voice Coming From?” she wrote overnight in June 1963 after hearing the news that Medgar Evers had been assassinated in Jackson. “Where is the Voice Coming From?” is a story narrated by the man who had killed Evers, written, of course, before Byron de la Beckwith had been identified and charged with the crime. Her imaginative portrait of the murderer was so accurate, however, that before she published it she revised it sufficiently to move the setting from Jackson. The question in the title goes straight to the point of the story: where does that voice, the voice of hatred and prejudice, come from?

The other story, “The Demonstrators,” more subtle, more complex, uses a murder in a Negro area of a Delta town to point up how little Black people impact the lives of White people as people: they are known more by their function in White society than by their value as human beings. Her response to the Civil Rights Movement, she always claimed, had to be that of a writer, an observer, rather than as a participant. She maintained that the writer, the artist, must remain independent of particular social phenomena, lest her work cease to be art and become propaganda.

Two masterpieces

After a long hiatus from writing during which she cared for her mother, Welty published two masterpieces in rapid succession. Losing Battles (1970) is a long comic novel set in the Mississippi hill country and The Optimist’s Daughter (1972) is a short novel set in a small community in central Mississippi. Both novels explore family relations. Losing Battles is structured around a reunion of the sprawling and multi-generational Renfro family and their conflicts with the local school teacher, Miss Julia Mortimer, and their hopes in their hero, Jack Renfro, who must escape from prison to attend the reunion.

The Optimist’s Daughter focuses on Laurel McKelva Hand’s return to Mississippi to nurture her father through a hospital stay, then to bury him. In the course of the novel, she must come to terms with her mother, dead years ago but remembered by everything in the house Laurel grew up in, and with her replacement, Laurel’s brash, loud, countrified stepmother, Faye. Welty received the Pulitzer Prize for Literature in 1973 for The Optimist’s Daughter. Welty’s autobiography, One Writer’s Beginnings (1983) is an equally moving portrait of her own family during the early years when she was trying to become a writer. Its publication revealed the highly autobiographical nature of The Optimist’s Daughter.

Always modest and unassuming, Eudora Welty often said that being a writer in the same state where William Faulkner wrote was like living near a mountain. Unspoken, and doubtless even unthought, in that statement is the fact that what usually lives near a mountain is another mountain. She died July 23, 2001.

Noel Polk, Ph.D., is professor of English at Mississippi State University.

Posted April 2003

-

Eudora, about age 5. She said her mother made most of her clothes. Photo ©Eudora Welty, LLC; Eudora Welty Collection; Mississippi Department of Archives and History -

The house on North Congress Street in Jackson where Eudora was born in 1909. Courtesy Mississippi Department of Archives and History.

-

Eudora, age 16, graduated from Jackson High School in 1925. Photo ©Eudora Welty, LLC; Eudora Welty Collection; Mississippi Department of Archives and History -

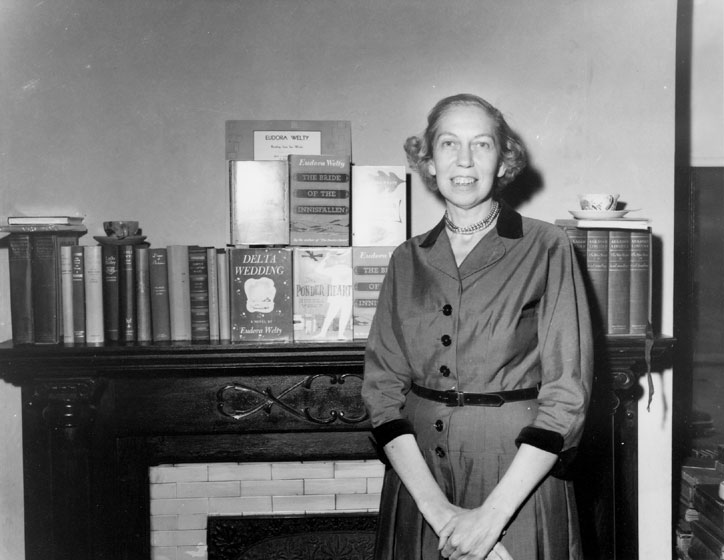

Eudora in 1954, the year The Ponder Heart was published. Courtesy Mississippi Department of Archives and History -

Eudora at her home on Pinehurst Street in Jackson. Photo by Frank Hains, 1970. Courtesy, Mississippi Department of Archives and History -

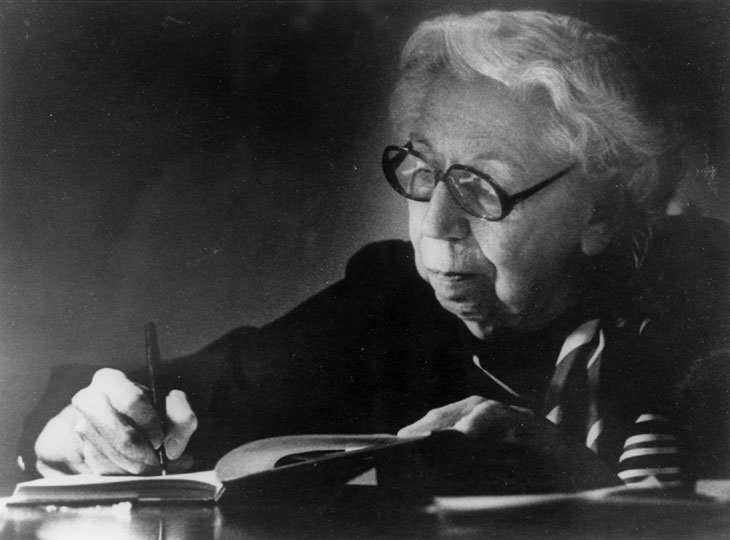

Eudora Welty autographing books. Photo by Terry James, 1984. Courtesy Mississippi Department of Archives and History

Selected Bibliography

Primary:

Eudora Welty. Stories, Essays, & Memoir. Ed. Richard Ford and Michael Kreyling. New York: Library of America, 1998.

——. Complete Novels. Ed. Richard Ford and Michael Kreyling. New York: Library of America, 1998.

——. Conversations with Eudora Welty. Ed. Peggy Whitman Prenshaw. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1984.

——. More Conversations with Eudora Welty. Ed. Peggy Whitman Prenshaw. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1996.

Secondary:

Michael Kreyling. Author and Agent: Eudora Welty and Diarmuid Russell. New York: Farrar Straus & Giroux, 1991.

——. Understanding Eudora Welty. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1999.

Rebecca Mark. The Dragon’s Blood: Feminist Intertextuality in Eudora Welty’s “The Golden Apples.” Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1994.

Noel Polk. Eudora Welty: A Bibliography of Her Work. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1994.

Peter Schmidt. The Heart of the Story: Eudora Welty’s Short Fiction. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1991.

Websites:

The Eudora Welty Newsletter: http://www.gsu.edu/~wwwewn/

Mississippi Writers Page: http://www.olemiss.edu/depts/english/ms-

writers/dir/welty_eudora/

The Eudora Welty Society: http://www.textsandtech.org/orgs/ews/

Mississippi Department of Archives and History: https://www.mdah.ms.gov/