Emblems, banners, standards, and flags are an ancient tradition that date from the early Roman Empire.

Flags are powerful symbols that signify dominion and sovereignty and express personal and political allegiance to a state or nation. Mississippi did not officially adopt a state flag until 1861, when it seceded from the United States and joined the Confederate States of America. Prior to that time, several flags had flown over the territory that would become the state of Mississippi on December 10, 1817.1

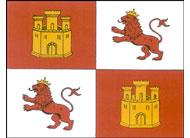

Although native Americans who inhabited Mississippi long before the period of European settlement used many symbols and emblems, typically made of metal and carried on poles or spears, the Spanish colors were the first to fly over Mississippi. (figure 1)

European flags

Hernando De Soto’s 600-member expedition into Mississippi in the winter of 1540 carried an emblem quartered in red and white depicting the golden castles of Castile and the red lions of Leon, the two dominant provinces of Spain. Christopher Columbus displayed this same standard from the mastheads of his tiny flotilla when he discovered the new world in 1492.2

After De Soto’s expedition, Spain did not attempt to colonize the lower Mississippi Valley, though it did establish settlements in what is now Florida.

In 1629, King Charles I of England granted Sir Robert Heath, an English nobleman, all the land “From Virginia to Florida and westward to the Great Ocean.” Because Heath made no serious attempt to colonize this region, in 1663 King Charles II reissued this land grant to a small group of English noblemen who established Carolina.

The British flag at that time was a combination of the red St. George’s Cross and the white St. Andrew’s Cross on a field of blue. It is unlikely that this flag, known as the British Union Flag, which was adopted in 1606 following the peaceful union of England and Scotland, ever flew over Mississippi, but it was technically the flag of dominion over that vast territory and has a place in the history of the flags over Mississippi.3 (figure 2)

While England held little more than an empty claim to the area that later became Mississippi, French explorers under Rene-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle laid formal claim and took possession of the Mississippi Valley on April 9, 1682, and named it Louisiana in honor of the Bourbon King Louis XIV. The Bourbon Flag of France was a field of white with three golden fleur-de-lys. This was the flag of dominion over Mississippi from 1682 until 1763.4 (figure 3)

Under the provisions of the Treaty of Paris of 1763, France ceded its territory east of the Mississippi River to England, and its territory west of the river, along with New Orleans, to Spain. Under this treaty, Spain also ceded Florida to England. Because of the transfer of this territory, Mississippi again came under British control and under the dominion of another flag.

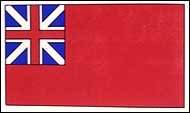

The new colors that were raised at Natchez, Baton Rouge, Mobile, and Pensacola in 1763 was the British Red Ensign that had been adopted by Queen Anne in 1707. The Red Ensign was a field of red with the British union in the canton corner. This was the flag that General Charles Cornwallis surrendered to General George Washington at Yorktown in 1781, and the flag of dominion over Mississippi from 1763 until 1783, when America gained its independence from England. (figure 4)

The Red Ensign was superseded as the national flag of Britain in 1801 when Ireland was united with England and Scotland. The red diagonal cross of Saint Patrick was added to the union of the Saint George's and Saint Andrew's crosses. The combination of all three crosses, in red and white on a blue ground, became the field of the new British flag. The new British flag never officially flew over Mississippi though it was raised briefly over Ship Island off the Mississippi Gulf Coast during the War of 1812.5 (figure 5)

American Revolution

During the early months of the American Revolution, an unofficial flag known as the Cambridge flag was raised by George Washington at his headquarters in Cambridge, Massachusetts. The field of the Cambridge flag, also known as the Grand Union flag, included seven red stripes and six white stripes. The British union was in the canton corner. (figure 6)

Mississippi came under the Cambridge flag as a part of Georgia and South Carolina during the Revolution.

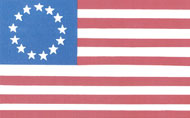

The Cambridge flag was superseded on June 14, 1777, when the Continental Congress adopted the Stars and Stripes. On the field of America’s first official national flag were seven red stripes and six white stripes. In the canton were thirteen white five-pointed stars arranged in a circle on a ground of blue.6 (figure 7)

Mississippi Territory

When the Mississippi Territory was established in 1798, the northern and southern boundaries were the thirty-two twenty-eight parallel, just above Vicksburg on the north, and the thirty-first parallel, just below Natchez on the south. The area above Vicksburg up to the state of Tennessee was American Indian territory and most of the area between Natchez and the Mississippi Gulf Coast was Spanish territory known as West Florida. Spain had regained this territory from Great Britain during the American Revolution. The Spanish Flag that flew over West Florida included, from top to bottom, a red bar, a yellow bar, and another red bar. Just off center in the yellow bar was the Spanish coat of arms. Known as the Spanish Bars of Aragon, the flag of Spain flew over the Mississippi Gulf Coast until 1810.7 (Figure 8)

Bonnie Blue Flag

In 1810, a small group of Americans living below the thirty-first parallel in Spanish Florida rebelled against Spain and established the Republic of West Florida. The flag adopted by that short-lived republic was a field of blue with one white star, an emblem that would later be heralded in song and verse as The Bonnie Blue Flag. The Republic of West Florida was eventually annexed by the United States and its territory was divided between Mississippi and Louisiana. (figure 9)

State of Mississippi

By the time Mississippi was admitted to statehood in 1817, the thirteen stars and thirteen stripes in the United States flag had increased to fifteen. With the prospects of many more states being added to the Union, Congress passed a law in 1818 which specified that the number of stripes on the flag would remain at thirteen, one for each of the original thirteen states, but a new star would be added to the canton on the Fourth of July following the admission of each new state.

Twenty-six years after the West Florida rebellion, Texas won its independence from Mexico. Many of the West Florida rebels had moved on to Texas and were prominent players in its revolution. Texas, known as the “Lone Star Republic,” also adopted the Bonnie Blue Flag as its official standard. When Texas was admitted to the Union in 1845, the new state flag included the Bonnie Blue star along with one red and one white bar.

The Bonnie Blue Flag resurfaced in Mississippi in 1861 when the state seceded from the Union and declared itself a sovereign and independent state. When the Secession Convention, which was meeting in the House chamber in the Mississippi capitol, approved the Ordinance of Secession on January 9, 1861, spectators in the balcony handed a Bonnie Blue Flag down to the delegates on the floor.

The appearance of that famous banner prompted a tumultuous response. Later that night, residents of Jackson paraded through the streets under the blue banner bearing a single white star. Harry McCarthy, a singer and playwright who observed the parade, was inspired to write The Bonnie Blue Flag, which, after Dixie, was the most popular song in the Confederacy.9

Magnolia Flag

From January 9, 1861, to March 30, 1861, the Bonnie Blue Flag was the unofficial emblem of the sovereign state of Mississippi, which had not yet joined the Confederate States of America. On January 26, the last day of the first session of the 1861 convention, the delegates approved the report of a special committee that had been appointed to design a coat of arms and “a suitable flag.”

The committee’s recommendation for an official flag was: “A Flag of white ground, a Magnolia tree in the centre, a blue field in the upper left hand corner with a white star in the centre, the Flag to be finished with a red border and a red fringe at the extremity of the Flag.”10 This emblem became known as the Magnolia Flag. (figure 10)

Under the pressure of time and the urgency of raising the “means for the defense of the state,” the delegates forgot to adopt an ordinance formalizing the flag committee’s report. When the delegates reassembled in March, however, that oversight was corrected. On March 30, again on the last day of the session, the delegates officially adopted the Magnolia Flag as the state flag of Mississippi.11

Flags of the Confederacy

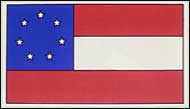

After its formal ratification of the Confederate Constitution on March 29, 1861, Mississippi became one of the eleven states of the Confederate States of America and authorized the governor “to have a Confederate flag [the Stars and Bars] made and hoisted.” (figure 11) Although Kentucky and Missouri sent delegates to the Confederate Congress and supplied troops to the Rebel army, and are represented in the thirteen stars in various Confederate flags, they were not officially members of the Confederacy.

The first national flag of the Confederacy, known as the Stars and Bars, was displayed widely in Mississippi and flew over government buildings as well as Confederate troops.

Although the second national flag, known as the Stainless Banner, was adopted May 1, 1863, almost two years before the Civil War ended, it is unlikely that it was used to any extent in Mississippi. (figure 12)

The Stars and Bars was still flying above the Confederate fortress of Vicksburg when it fell July 4, 1863. By then, the lower Mississippi Valley, including Memphis, Vicksburg, Natchez, Baton Rouge, New Orleans, and much of the Mississippi Gulf Coast, was under Federal control.

Because the Confederate Congress adopted the third national flag barely a month before the surrender at Appomattox, it probably did not fly over any government agencies or troops anywhere in the Confederacy. Regardless of the extent of their use in Mississippi, all three of the national flags represent a period of the Confederacy and they all have a place in the history of the flags over Mississippi. (figure 13)

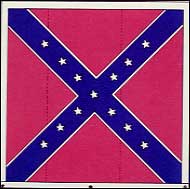

Although it was not adopted as a national flag of the Confederacy or as the official battle flag of the Confederate army, the Beauregard battle flag was the banner under which thousands of Confederate soldiers marched into battle. It was used by Mississippi troops, especially during the time that General P.G.T. Beauregard commanded Rebel forces at Shiloh and Corinth in the spring of 1862. (figure 14)

The Mississippi regiments under General Robert E. Lee’s command also fought under the Beauregard flag after its adoption as the flag of the Army of Northern Virginia.12

Although it was not widely used or displayed during the Civil War, the Magnolia Flag remained the official state flag of Mississippi until 1865. In the aftermath of the Civil War, a constitutional convention assembled in Jackson, Mississippi, on August 14, 1865, to revoke and repeal many of the actions taken by the Secession Convention of 1861. On August 22, the convention declared the Ordinance of Secession null and void and repealed several other ordinances. Among those repealed was the ordinance adopting a coat of arms and a state flag. This action left Mississippi without an official flag.13

State Flag of Mississippi

Almost thirty years later, on January 22, 1894, Governor John Marshall Stone sent a written message to the Mississippi Legislature calling its attention to the fact that Mississippi did not have a state flag or a coat of arms and urged the lawmakers to adopt an official state emblem and a coat of arms. The legislature responded quickly to Governor Stone’s suggestion and sent him a bill February 6 creating a state flag. The description of the flag recommended by the joint legislative committee was:

“One with width two-thirds of its length, with the union square in width, two-thirds of the width of the flag; the ground of the union to be red and a broad blue saltier thereon bordered with white and emblazoned with thirteen (13) mullets or five-pointed stars, corresponding to the number of the original States of the Union; the field to be divided into three bars of equal width, the upper one blue, the center one white, the lower one red; the national colors; the staff surmounted with a spear-head and battle-axe below; the flag to be fringed with gold, and the staff gilded with gold.”14 (figure 15)

According to the best information available, Senator E.N. Scudder of Mayersville, a member of the Joint Legislative Committee for a State Flag, designed Mississippi’s new flag.

In 1924, Fayssoux Scudder Corneil, Senator Scudder’s daughter, stated in an address to the annual convention of the Mississippi Division, United Daughters of the Confederacy, that her father designed the flag and included the Beauregard battle flag in the canton corner to honor the Confederate soldier. Corneil recalled:

“My father loved the memory of the valor and courage of those brave men who wore the grey…. He told me that it was a simple matter for him to design the flag because he wanted to perpetuate in a legal and lasting way that dear battle flag under which so many of our people had so gloriously fought.”15

On February 7, 1894, Governor Stone, a Confederate veteran and former colonel of the Second Mississippi Infantry Regiment, signed into law the bill creating the state flag.16

With its bold lines and bright colors, the battle flag in the canton, the field fringed in gold, the new state flag was a compelling symbol.

The emblem adopted in 1894 remained the official state flag only until 1906 when a legal oversight resulted in the repeal of the law establishing it. In 1906, Mississippi adopted a revised code that included a provision that repealed all general laws that were not reenacted by the legislature or brought forward in the new code.

For some reason, which contemporary documents and records do not reveal, the compilers of the new code did not bring forward the law that created an official state flag and a coat of arms. Because of this oversight, which surely must have been inadvertent, the state of Mississippi does not have an official state flag.17

The 1906 repeal of the law establishing a state flag completely escaped the notice of Dunbar Rowland, the director of the Mississippi Department of Archives and History, and editor of the Official and Statistical Register of the State of Mississippi. The register, which is published every four years, is now edited by the Secretary of State and is known as the Blue Book. In the 1908 edition of the register, Rowland included a full-page, four-color picture of the “State Flag of Mississippi.”

The repeal also escaped the notice of the state legislature, which passed a flag desecration statute April 8, 1916, making it illegal to deface or disfigure “the flag…of the State of Mississippi…”

A year later when The Annotated Mississippi Code Showing the General Statutes in Force August 1, 1917 was adopted, William Hemingway, a Jackson attorney who compiled the code, did not include the 1894 statute establishing the flag, but he did include a reference to the state flag in Section 903 entitled: “Flags – Desecration of the nation and state prohibited.”18

Even though Mississippi did not legally have an official state flag after 1906, no one seemed to have known it and practically everyone who was interested in such things presumed that it did and continued to fly the flag that was adopted in 1894. Whether it was the flag by law or custom, the Mississippi state flag with its prominent display of the Beauregard battle flag eventually became a symbol that stirred the deep passions and the power of memory.

When the Beauregard battle flag, which is identified in the public mind as the Rebel or Confederate flag, resurfaced as a southern symbol of resistance to the Civil Rights Movement in the 1960s, the passions that gave it life in the 1860s were rekindled.

Although America is not yet a race-neutral society, and full racial justice is still a goal and not a fact, the Civil Rights Movement was one of America’s great legal, social, and cultural successes.

The Movement overturned virtually all of the nation’s racially discriminatory laws and opened up new avenues of power and influence to Black Americans. After achieving a fundamental and substantive change in American race relations, many Black people eventually turned their attention to the symbols and icons of racial discord, which are the vestiges and residue of southern resistance to racial equality.

In the 1970s, following the racial integration of Mississippi’s public school system and the integration of intercollegiate athletics, the prominence of the battle flag at high school and college sporting events prompted a discomfort and eventually a deep resentment among Black Mississippians in whose recent memory the flag was identified with the Ku Klux Klan, the White Citizens' Council, and various hate groups who perpetrated heinous crimes against Black people and hoisted the Rebel flag as a symbol of their belief and commitment to white supremacy.

As the battle flag was becoming increasingly associated with the advocates of White supremacy, historical organizations and southern heritage groups were unable to separate or distinguish the historical character of the battle flag or protect or insulate it from the political agenda of its modern bearers.

The simmering public controversy over the Rebel flag exploded at the University of Mississippi in 1983 when John Hawkins, the university’s first Black cheerleader, announced that he would not wave or distribute Rebel flags at Ole Miss football games. Friends and foes of the flag engaged in an ongoing public discourse on southern history and heritage, on slavery and racial suppression, on the alleged and actual causes of the Civil War.19 (figure 16)

Amidst this tumult, the late Aaron Henry, a member of the Mississippi Legislature and president of the Mississippi Conference of the NAACP, introduced a bill to remove the battle flag from the state flag at the beginning of the 1988 legislative session. This bill was never brought to the floor for a vote, nor were any of the others he introduced in 1990, 1992, and 1993.20

Following the failure of these bills, the Mississippi NAACP filed a lawsuit April 19, 1993, in the Hinds County Chancery Court seeking “an injunction against any future purchases, displays, maintenance or expenditures of state funds on the State Flag” on the grounds that its display violated the “constitutional rights [of African-Americans] to free speech and expression, due process and equal protection as guaranteed by the Mississippi Constitution.”21 (figure 17)

After the Chancery Court dismissed the suit June 14, 1993, the NAACP appealed to the Mississippi Supreme Court. While adjudicating this case, the Court recognized the inadvertent 1906 repeal of the law establishing an official state flag.

Notwithstanding the fact that the state had no official state flag, the Supreme Court upheld the lower court’s dismissal of the suit. The Court further declared that the display of the flag, however offensive it might be to some citizens, “does not deprive any citizen of any constitutionally protected right.”

The Court further stated that a dispute over the adoption and display of a state flag is a political issue that must be resolved by the legislative and executive branches of state government and not the judiciary.22

Note: In November 2020, the voters of Mississippi approved a new state flag called the "In God We Trust Flag" (figure 18). During the summer of 2020, after protests about racial injustice regarding the murder of George Floyd, the Mississippi Legislature passed a bill retiring the 1894 flag and creating the Commission to Redesign the Mississippi State Flag, which came up with the current state flag.

David G. Sansing, Ph.D., is professor emeritus of history, University of Mississippi. This article was updated in September 2021.

-

(figure 3) Bourbon Flag of France -

(figure 4) British Red Ensign -

(figure 5) St. Patrick’s Cross -

(figure 6) The Cambridge Flag -

(figure 7) The Stars and Stripes -

(figure 8) Spanish Bars of Aragon -

(figure 9) Bonnie Blue Flag -

(figure 10) The Magnolia Flag -

(figure 11) The Stars and Bars -

(figure 12) The Stainless Banner -

(figure 13) The Third National Flag of the Confederacy -

(figure 14) Beauregard Battle Flag -

(figure 15) Mississippi State Flag -

(figure 16) Rebel Flag at Ole Miss football game. -

(figure 17) Newspaper clipping: Rebel Flag: An Enduring Symbol. -

(figure 18) "In God We Trust" flag adopted in 2020

Sources

1. See Cyril E. Cain, Flags Over Mississippi (n.p., 1954). Much of the information on the European flags over Mississippi comes from this early study of state flags. See also Myrtle Garrison, Stars and Stripes (Caxton Printers Ltd., 1941); Whitney Smith, The Flag Book of the United States (William Morrow & Co., 1970); and Flags Through the Ages and Across the World (McGraw-Hill, 1975)

2. Cain, Flags Over Mississippi, 9

3. Ibid, 11

4. Ibid, 13

5. Ibid, 15

6. Ibid, 17,18

7. Ibid, 21

8. Devereaux D. Cannon, Jr., The Flags of the Confederacy, An Illustrated History (St. Lukes Press, 1988), 31-33

9. Ibid; Cain, Flags Over Mississippi, 22-23

10. Journal of the State Convention … January 1861 (E. Barksdale, 1861), 89-90

11. Journal of the State Convention … March 1861 (E. Barksdale, 1861), 27, 35, 42, 43, 77, 86

12. For details on the adoption of the various Confederate flags, see Mrs. Lucile Lange Dufner, “The Flags of the Confederate States of America,” (MA Thesis, University of Texas, 1944); E. Merton Coulter, “The Flags of the Confederacy,” Georgia Historical Quarterly, vol. 37 (1953), 187-199; Cannon, Flags of the Confederacy; Howard M. Madaus and Robert D. Needham, The Battle Flags of the Confederate Army of the Tennessee (Milwaukee Public Museum, 1976); Richard Rollins, (ed.), The Returned Battle Flags (Rank and File Publications, Redondo Beach, CA edition, 1995); Alan K. Sumrall, Battle Flags of Texans in the Confederacy (Eakin Press, Austin, Texas, 1995); and Smith, Flag Book of the United States, and Flags Through the Ages

13. Journal of the Constitutional Convention … August 1865 (E. M. Yerger, State Printer, 1865), 214, 221-222

14. House Journal, 1894 (Clarion-Ledger Publishing Co., 1894), 193-194, 350-351

15. See a copy of Corneil’s address in the State Flag Subject File, Mississippi Department of Archives and History. This file, much of which was compiled by Anne Lipscomb Webster, head of reference services, Archives and Library Division, contains a wealth of information on the state flag.

16. Laws of Mississippi, 1894 (Clarion-Ledger Publishing Co., 1894), 33

17. See Section 13, Mississippi Code 1906 (Brandon Printing Co., 1905)

18. Laws of Mississippi, 1916 (E.H. Clarke and Bro., 1916), 177; The Annotated Mississippi Code … 1917 (Dobbs-Merrill Co., n.d.), 902

19. For a discussion of the Rebel flag controversy at Ole Miss, see David G. Sansing, The University of Mississippi, a Sesquicentennial History (University Press of Mississippi, 1999), 281-314, 321-342

20. See copies of Representative Henry’s bill in State Flag Subject File, MDA

21. See copy of the Mississippi Supreme Court ruling, NO. 94-CA-00615-SCT, Ibid

22. Ibid