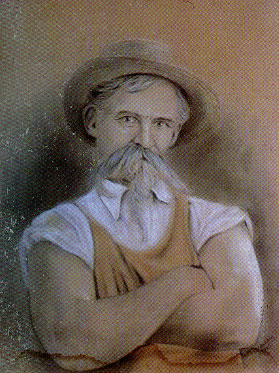

George E. Ohr (1857-1918) has been called the first art potter in the United States, and many say the finest. Ohr was born in Biloxi, Mississippi, the son of young German immigrants, Johanna Wiedman and George Ohr. Both Alsatians, the Ohrs had moved to Biloxi after a brief stop in New Orleans, their port of entry in 1853. George Ohr Sr. established the first blacksmith shop in Biloxi and later opened the first grocery store there. His son, George Edgar Ohr, would grow up to be a flamboyant, dedicated potter and a memorable figure in his hometown.

Young George had a restless adolescence in the confusion of the post-Civil War years. After learning the blacksmith trade from his father, George Ohr at fourteen left for New Orleans, where he tried nineteen different jobs. When he was twenty-two, a boyhood friend from Biloxi, Joseph Fortuné Meyer, offered Ohr a job as an apprentice potter in New Orleans. It set the course of George Ohr’s life. Ohr later wrote, “When I found the potter's wheel I felt it all over like a wild duck in water.”

The potter begins

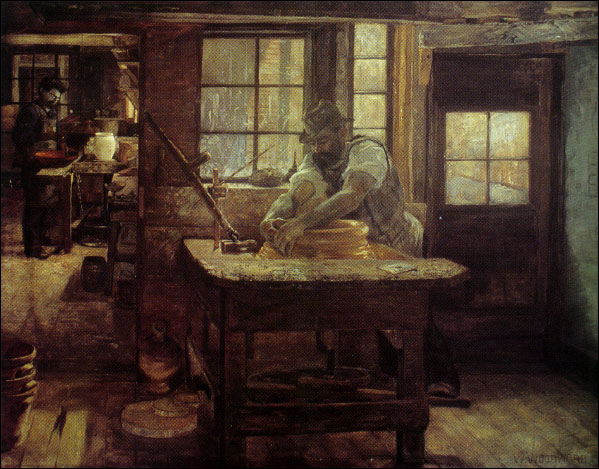

After he had learned his craft, he left New Orleans for a two-year, sixteen-state tour of potteries in the United States to learn all he could about the profession. He returned to Biloxi and built his pottery shop himself. He fabricated all of the ironwork, made the potter's wheel, the kiln, rafted lumber down river, sawed it into boards, and constructed his shop. Joseph Meyer had taught him how to use the natural resources around Biloxi, how to locate and dig clay from the banks of the nearby Tchoutacabouffa River. Ohr rowed his skiff up the river, dug the clay, and floated his load back down the Tchoutacabouffa.

When his kiln and supplies were ready, he worked hard at the potter’s wheel producing practical items like jugs, mugs, planters, flowerpots, and water bottles. He found time to produce finer work, as well. Ohr startled the art world at the 1885 World's Fair in New Orleans with his extraordinary pots. He exhibited some six hundred pieces, which were stolen before he could get them back to Biloxi.

Mad potter of Biloxi

One good outcome of the World’s Fair was his courtship and marriage to a young German woman whom he had met in New Orleans, Josephine Gehring. Soon afterwards, Meyer again invited Ohr to work with him at the newly created New Orleans Art Pottery. For two years, 1888 to 1890, Ohr worked in New Orleans throwing huge garden pots. His work was competently done but with no hint of his later virtuosity in creating delicate, imaginative pots.

After the New Orleans Art Pottery went out of business, Ohr returned to Biloxi and again went into serious production for himself. Biloxi Art and Novelty Pottery, as he called his pink shop, in no time was crammed with vessels of all shapes, sizes, and decorations, “rustic, ornamental, new and ancient shaped vases, etc.” As he created his pots, he also created himself. Ohr presented himself as a wildly eccentric person — brash, mischievous, wearing flowing beard and hair, and hooking his moustache over his ears. He gave his business a carnival atmosphere.

His shop became an established tourist attraction on the Mississippi Gulf Coast. At his shop, fascinated visitors could watch an entertaining performance by the “Mad Potter of Biloxi” and buy mementos of their trip.

Tragedy struck in the fall of 1894 when a fire wiped out the pottery along with twenty other business establishments in Biloxi. Ohr rescued some of his charred “clay babies,” as he called his pots, and began anew. Soon Ohr had rebuilt a grand new pottery with a five-story tower shaped like a pagoda. He called it Biloxi Art Pottery Unlimited and the tourists returned in great numbers.

In the meantime, Meyer had become potter at Sophie Newcomb College (now a part of Tulane University) and again asked Ohr to work with him in New Orleans. From 1897 to 1899 Ohr divided his time between Biloxi and New Orleans, working constantly to supplement his income for his growing family. He and Josephine had a total of ten children, but only five survived to adulthood.

Creating exotic forms

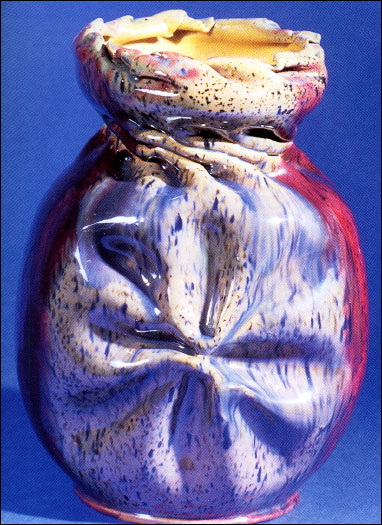

His cups and saucers, plaques of local sites, Mississippi mule ink wells, tiny artist pallets, puzzle mugs, and molded souvenirs of all kinds, were popular with tourists and local residents. But his extraordinary skill at the potter's wheel making his artware brought him to the attention of the ceramic art world. Ohr threw extremely delicate, thin-walled pots which he manipulated into exotic forms by twisting, denting, ruffling, and folding the clay into vases, “no two alike.” He said in an interview, “I brood over [each pot] with the same tenderness a mortal child awakens in its parent.”

Ohr's serious creations did not find popularity with the public. And because the Victorian art pottery of the day was carefully controlled and decorated, Ohr’s energetic and expressionistic treatment of clay was too wild even for refined tastes. Ohr was passionate about his work and supremely confident in his talent. He wrote to an art critic, “I am making pottery for art’s sake, God’s sake, the future generation, and — by present indications — for my own satisfaction, but when I'm gone my work ... will be prized, honored and cherished.” In 1899 he packed up eight pieces and sent them to the Smithsonian Institution. One of the pots was inscribed, “I am the Potter Who Was.”

Cited as a genius

The 1904 Louisiana Purchase International Exposition was both a triumph and a disaster for Ohr. He won a Silver Medal for the most original art pottery. He displayed several hundred of his finest pieces and sold nothing. No one would pay the prices he demanded. Nonetheless his virtuosity in throwing pots and his glazes were admired by ceramic critics and potters. He was called “one of the most interesting potters in the United States” in the April 1899 edition of the journal China, Glass, and Pottery Review. In lectures at Alfred University in New York, the famous ceramics teacher Charles Binns cited Ohr as a genius. Still, Ohr’s refusal to sell his fine pieces at attractive prices prohibited him from the recognition and success for which he longed.

Ohr gave up his profession as potter in 1909. The famous ceramic shop landmark became Biloxi's first auto repair shop, run by his sons. Urged to sell his pots by his family, Ohr instead packed up the several thousand pots that he could not or would not sell and stored them away. He was confident that the world would someday recognize him as “the greatest art potter on earth.” He died of cancer in Biloxi in 1918.

Acclaim, at last

The artistic acclaim that he had envisioned came fifty years after his death. In 1968, James W. Carpenter, an antiques dealer from New Jersey looking for old cars, happened upon the crates of pots stored in the Ohr Boys' Auto Repair Shop. He subsequently bought the entire cache of 6,000 pieces for $50,000. As the pots began to come on the market, art pottery collectors were intrigued, art historians began to re-evaluate his importance, and his pots began to sell for thousands of dollars.

Today Ohr is a cult figure in the art world. One contemporary critic has described his work as “boldly fixed at the extreme of chance, spontaneity, natural asymmetry, calculated imperfection, rustic vigor, wit, and mischief.”

His hometown of Biloxi, once indifferent to his art, established the George E. Ohr Arts and Cultural Center in 1994. A new museum, The Ohr-O’Keefe Museum of Art designed by architect Frank Gehry, opened in 2010.

Patti Carr Black is the author of Art in Mississippi (1720-1980) from which this article is adapted. Art in Mississippi, copublished by the Mississippi Historical Society, the Mississippi Department of Archives and History, and the University Press of Mississippi, is the first book in the Society’s Heritage of Mississippi Series. Black is the former director of the Old Capitol Museum, Mississippi Department of Archives and History.

Sources

Patti Carr Black , ed., The Biloxi Art Pottery of George Ohr (Jackson, Mississippi Department of Archives and History 1978)

Garth Clark, ed., The Mad Potter of Biloxi: The Art and Life of George E. Ohr (New York, Abbeville Press, 1989)

Eugene Hecht, No Two Alike: the Legacy of George E. Ohr, the Mad Potter of Biloxi (1994)

Gulf Coast Historical and Humanities Conference, Threads of Tradition and Culture along the Gulf Coast, 1986.