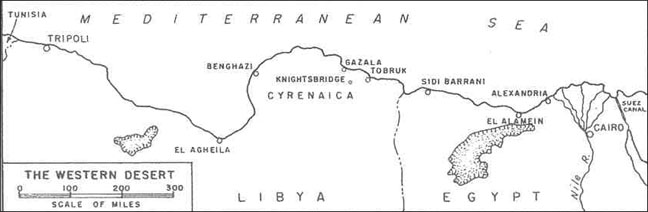

World War II was truly a world war. All of the major countries and a large number of small nations were drawn into the fight. Even countries that tried to remain neutral found themselves in the conflict either by conquest or by being in the path of the campaigns of the major powers. For example, in 1940, more than a year before the United States entered the war, the major powers — Britain, Italy, and Germany — fought important battles in Egypt, Tunisia, and Libya in North Africa.

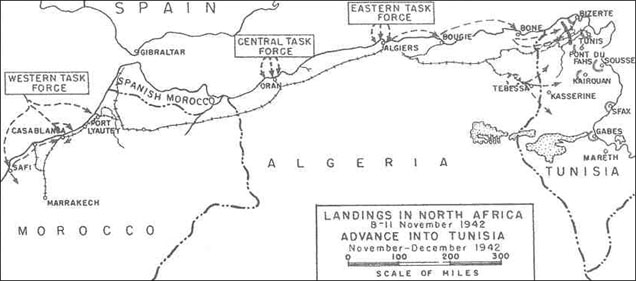

Not until November 1942, almost a year after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, did American forces enter the fight in North Africa. U.S. forces made amphibious landings at the North African cities of Casablanca, Oran, and Algiers. German and Italian forces in Libya were then caught in a vise — Americans advanced from the west along the North African coast to Tunisia while British troops advanced from the east out of Egypt. The Germans and Italians had to defend on two fronts — the British front on the east and the American front on the west. (See the maps on the left.)

Afrika Korps becomes POWs

The famous "Afrika Korps," under German General Erwin Rommel, made up of German and Italian tanks and trucks, was besieged in Tunisia and fought on until May 1943. In March, Rommel flew to Germany to plead with Hitler for reinforcements. Instead, Hitler recalled Rommel from North Africa.

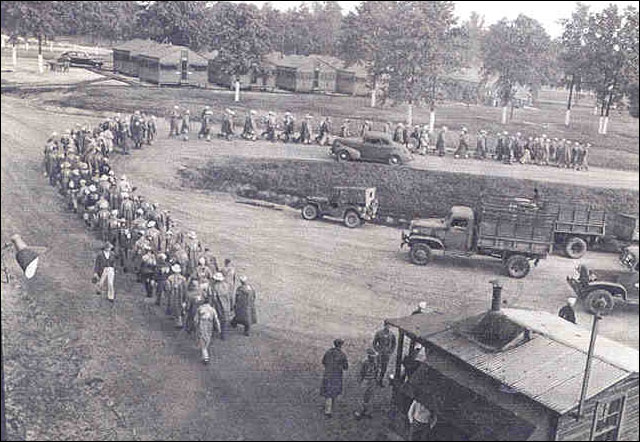

Two months later, the Afrika Korps became prisoners of war of the United States and Great Britain. General Jurgen Von Arnim, Rommel's replacement, went into captivity as a prisoner of war along with 275,000 German and Italian soldiers. They were housed in tents surrounded by barbed wire. Food, water and other essentials had to be transported to the German and Italian prisoner-of-war compounds. A shipping shortage plagued the allies. How could they feed and house the German and Italian prisoners in Africa while the United States and Great Britain needed all ships to bring troops and equipment from America for the Normandy invasion? After unloading their cargoes in Great Britain, many of these ships returned empty to the United States.

To help alleviate the shipping problems, a decision was made by the U.S. government to bring the German and Italian prisoners of war from North Africa to prisons in the United States. It would be less burdensome and less costly to house and feed the captured men in the United States. Additionally, the prisoners of war (POWs) could be put to work in non-military jobs. In the last four months of 1943, German and Italian prisoners of war began arriving in the United States from their compounds in North Africa.

A German soldier, who fought in North Africa, kept a diary from his surrender on May 13, 1943, to his arrival some months later at Camp Clinton, just outside Jackson, Mississippi. He and his fellow veterans of the now defeated Afrika Korps were marched and trucked to the city of Algiers in Algeria, North Africa, where they were put on ships that carried them to the Algerian port of Oran. They were then marched to a POW compound in the desert where they were housed in a "cage" (the name used by American soldiers for a barbed wire enclosure).

POWs arrive in Mississippi

Four weeks later the POWs were trucked from the cage back to Oran on the North African coast. There they boarded ships for the journey across the Atlantic Ocean to the United States. After two weeks at sea, the ship docked at the Port of Norfolk, Virginia, on August 4, 1943. At Norfolk the prisoners who were assigned to Camp Clinton expected a slow freight train to carry them to their destination. Instead, they boarded a sleek, comfortable passenger train. Two days later they arrived at Camp Clinton.

Camp Clinton, one of four major POW base camps established in Mississippi, was unique among the other camps because it housed the highest ranking German officers. Twenty-five generals were housed there along with several colonels, majors, and captains. The high ranking generals had special housing. Lower ranking officers had to content themselves with small apartments. General Von Arnim, Rommel's replacement, lived in a house and was furnished a car and driver. Some people swore that General Von Arnim attended movies in Jackson because the movie theater was the only air-conditioned place in town.

Other major POW camps in Mississippi were established at Camp McCain near Grenada, Camp Como in the northern Delta, and Camp Shelby near Hattiesburg. The four base camps were large compounds designed to house large numbers of POWs. Camp McCain housed 7,700, Camp Clinton 3,400, and Camp Shelby housed 5,300. Camp Como originally held 3,800 Italian soldiers, but the Italians were soon moved out of Mississippi and replaced by a smaller number of Germans.

U.S. adheres to Geneva Conventions

These base camps had most of the facilities and services that could be found in a small town — dentists, doctors, libraries, movies, educational facilities (English language was the most popular course) and athletics (soccer was the most popular sport). POWs were guaranteed by an international treaty called the Geneva Conventions to get food, clothing, and medical care equal to that of their captors.

POWs were housed in barracks that held up to fifty men. Each five barracks had a mess hall with cooks, waiters, silverware, and by all accounts very good food. Food was not a complaint for the prisoners. In fact, most of the food was prepared by German cooks with ingredients furnished by the U.S. Army. A sample breakfast was cereal, toast, corn flakes, jam, coffee, milk, and sugar. A typical lunch was roast pork, potato salad, carrots, and ice water. Supper might be meat loaf, scrambled eggs, coffee, milk, and bread. Beer could be bought in the canteen.

Individual barracks fielded teams for sports as diverse as horseshoes, volleyball, and soccer. Athletic contests among the barracks were highly competitive, and tournaments were arranged to select the winners. Prisoners at Camp Shelby reported the outcome of athletic events in the camp's newspaper, the Mississippi Post.

POWs were allowed to keep their uniforms for ceremonial occasions such as funerals and holidays. These uniforms, however, had already seen much wear. For everyday wear, POWs wore black or khaki shirts and pants with the letters "PW" stenciled in paint on each leg. Winter clothes were wool jackets and pants. Athletic shorts and shirts were issued for games.

Under the Geneva Conventions, officers could not be forced to work. However, soldiers could be required to work if the tasks did not aid their captor's war efforts. If the POWs worked outside the compound, they received a payment of 80 cents a day. This was enough money to buy cigarettes and other items that were available in the prison canteen. Most chose to work. The kinds of work done by these POWs depended on the region in Mississippi where they were housed.

POWs pick cotton, plant trees

In 1944, the four base camps — Camp McCain, Camp Como, Camp Clinton, and Camp Shelby — developed fifteen branch camps. Ten of these camps were in the Delta. They were located at Greenville, Belzoni, Leland, Indianola, Clarksdale, Drew, Greenwood, Lake Washington, Merigold, and Rosedale. These camps furnished POWs to work in the cotton fields where in the spring under a hot sun, they chopped the weeds away from the young cotton plants with a hoe. In the fall they picked the cotton — a job they disliked. Mechanical cotton pickers had not yet been perfected, so cotton had to be picked by hand. The prisoners dragged heavy canvas bags, and as they filled the bag with cotton, the sack became heavier. As they pulled the cotton from the bolls, the pointed bolls scratched and punctured their hands. The summer heat of the Delta was much like that of the North African desert.

The other five branch camps were located in south Mississippi in the pine lands. They were at Brookhaven, Picayune, Richton, Saucier, and Gulfport. Much of the POW's work was in forestry. They planted seedlings, cut timber and pulpwood, and cleared lands for various purposes. They worked to complete Lake Shelby, a small lake a few miles from Camp Shelby.

Perhaps the most intricate and useful work that was done by German POWs in Mississippi was the Mississippi River Basin Model. The U.S. Corps of Engineers was in charge of major waterways, and they had long wanted to build a one-square-mile model of the entire Mississippi River basin. Such a model could be of great value in predicting floods and in assessing the water flow of the Mississippi River and its tributaries.

Chief of the United States Corps of Engineers, Major General Eugene Reybold saw an opportunity to build the model. He would use German POWs from Camp Clinton to clear a one-square-mile area near Jackson. Using hundreds of wheelbarrows and shovels, the POWs prepared the site. They dug drainage ditches, they constructed miniature streets and bridges, and they formed the one-square-mile landscape into a miniature Mississippi River basin.

Most German POWs were not dedicated Nazis. Yet small numbers of fanatical Nazis frequently intimidated the other prisoners. At Camp Clinton a German soldier was killed by these fanatical Nazis. The bitterness between the Nazis and the other prisoners threatened to become a major problem. The American authorities intervened and shipped the Nazis to special camps in Oklahoma.

Attempts at the great escape

Captured soldiers often feel they have a duty to escape, but the possibilities of successful escapes were remote in Mississippi. Most POWs in the state were content to wait out the end of the war. Nonetheless, some POWs tried to escape. Escapees found it relatively easy to get out of the prison camps. They could walk off from a cotton field or slip off into the woods. They were hardly ever successful. Their German accents, their POW clothes, or their lack of money gave them away. Despite their failures, some POWs kept trying.

At Camp Clinton the prisoners dug a tunnel 100 feet long. They hoped to tunnel under the fence. They concealed in their pants legs the dirt that they had dug out for the tunnel and then scattered the dirt around the prison grounds. They even installed light bulbs to light the tunnel. The tunnelers were caught 10 feet from the fence.

At Grenada, near Camp McCain, four prisoners were discovered eating lunch in a Grenada restaurant. More than thirty POWs walked away from a camp at Belzoni. The local police, FBI, state highway patrol, and volunteers searched the surrounding area. The missing POWS were soon found walking the streets of Belzoni looking into the store windows. They explained that they had become bored in the camp.

Perhaps the strangest escape of all involved a German pilot and the wife of a Delta planter. The wife fell in love with Helmut Von der Aue during the several months that he worked on the plantation. The German POW and the planter's wife were arrested in Nashville, Tennessee. The pilot explained that they were on their way to the east coast to steal an airplane and fly to Greenland.

POWs return home

The war in Europe ended in May 1945, but the POWs remained in the compounds and continued to work — some for almost a year after the war ended. American soldiers were mustered out of the military quickly and efficiently, but President Harry Truman decided that a labor shortage existed in the United States and that the POWs should remain in this country until the labor shortage was over. Some POWs did not get home to Germany until mid-1946. They had been in the Mississippi camps almost three years.

Over the years since 1946, German veterans have come back to Mississippi to see the camps that they lived in as young men. They are sad to learn that the camps were torn down after the war. The German POWs in Mississippi were probably aged 18 to 20 when they were captured in North Africa in 1943. The survivors of the Mississippi prisoner-of-war camps are now very old. But many of those who are alive still come back to Mississippi to remember their experience. In a strange way the camps saved their lives. Unlike many other German soldiers who were killed in the war, these POWs survived. When they entered the Mississippi camps, their war was over.

John Ray Skates, Jr., Ph.D., emeritus professor of history, University of Southern Mississippi, is the author of The Invasion of Japan: Alternative to the Bomb, University of South Carolina Press, 1994.

Lesson Plan

-

POW Count Stolberg, a German brigadier general at Camp Clinton. Courtesy, Armed Forces Museum at Camp Shelby, Hattiesburg, Mississippi -

The Western Desert

-

Landings in North Africa -

POW barracks. Courtesy, Armed Forces Museum at Camp Shelby -

A German funeral at Camp Shelby for a prisoner of war who committed suicide. Courtesy, Armed Forces Museum at Camp Shelby -

German POWs in their various uniforms at Camp Shelby. Courtesy, Armed Forces Museum at Camp Shelby -

Prisoners marching through Camp Shelby. Courtesy, Armed Forces Museum at Camp Shelby -

German soccer team at Camp Shelby, 1944 champions. Courtesy, Armed Forces Museum at Camp Shelby -

German POWs with "PW" painted on their pants legs. Courtesy, Armed Forces Museum at Camp Shelby

Sources and Further Readings

Merrill R. Prichett and William L. Shea, "The Enemy in Mississippi (1943-1946)," The Journal of Mississippi History, November 1979.

Barry W. Fowler, Builders and Fighters: U.S. Army Engineers in World War II, Office of History, United States Corps of Engineers, Fort Belvoir, Virginia, 1992.

Forrest Lamar Cooper, "The Prisoners of War: Grenada's Camp McCain was more than a training base, it was a World War II prison," Mississippi, July/August 1989, pp. 71-73.

Maxwell S. McKnight, "The Employment of Prisoners of War in the United States," International Labor Review, July 1944.

Walter Rundell, Jr., "Paying the POW in World War II," Military Affairs, Fall 1958.

Diary of a German soldier, captured in North Africa and transported to Camp Clinton, near Jackson, Mississippi. Typescript in Camp Shelby Archives.

Report, Headquarters, Prisoner of War Camp, Camp Shelby, Mississippi, 23 October 1943.

Report, Army Services Forces, Fourth Service Command, Camp Shelby, Mississippi, 1 March 1945.