The six southern states of South Carolina, Mississippi, Georgia, Alabama, Louisiana, and Florida met February 4, 1861, in convention at Montgomery, Alabama, and established the Confederate States of America.

They were soon joined by Texas, and after the firing on Fort Sumter on April 12, they were joined by Tennessee, North Carolina, Arkansas, and Virginia. Missouri and Kentucky were prevented from seceding by the presence of federal troops, but both states sent unofficial representatives to the Confederate Congress and both supplied troops to the Confederate Army.

The eleven seceding states, plus Missouri and Kentucky, are represented in the constellation of thirteen stars in the Confederate flag. The other two states, Maryland and Delaware, did not secede.1

The first national flag of the Confederate States of America was adopted at the Montgomery convention. After the delegates had established the Confederacy, a special committee was appointed to design a flag and a seal for the new nation.

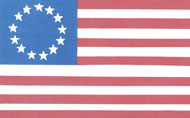

Walker Brooke, a Mississippi delegate, offered a resolution to instruct the committee to design a flag as similar as possible to the American flag, the Stars and Stripes. (figure 1)

Brooke, and several other delegates, praised the Stars and Stripes and some even suggested that the CSA adopt the American flag with no change at all. However, the patriotic fervor that swept through the convention forced Brooke to withdraw his resolution.2

The flag committee was swamped with so many models and designs that the committee chairman, William Porcher Miles of South Carolina, lost track of the number. When Miles made his report March 5, he explained to the convention that the committee had divided the proposed designs into two classes: 1) variations of the American flag, and 2) highly original and elaborate designs.

Although the chairman personally considered the American flag a symbol of oppression and tyranny, the committee's recommended design retained “a suggestion of the old Stars and Stripes.”3

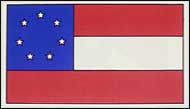

In explaining the committee's recommendations, Miles said the basic colors red, white, and blue were retained. But rather than displaying red and white stripes, the Confederate flag displayed two red bars and one white bar. In the canton, or union corner, a star for each state was placed in a field of blue.

This flag, which almost immediately became known as the Stars and Bars, was raised at Montgomery on March 4, 1861. (figure 2)

The Stars and Bars, though popular with many Confederate officials, did not capture the imagination of the general public who seemed disappointed that their new nation was symbolized by such an unimaginative emblem. The design of the Stars and Bars was an unfortunate compromise. It looked too much like the American flag for some Confederates, and not enough like it to others.4

Confusion on Battlefield

The resemblance between the two flags became apparent at the American Civil War's first call to battle.

In early July 1861, General P.G.T. Beauregard directed his quartermaster to issue to each of his troops a red flannel badge to be worn on the left shoulder. Those red badges would distinguish Confederate soldiers from Federal soldiers whose uniforms were similar in style, color, and markings.

Even with these distinctive red badges, the difficulty of identifying the opposing army especially at great distances created much anxiety and near catastrophe for the Confederates on July 21 at Manassas Junction, near Bull Run Creek, the first major battle of the Civil War.

About 4 o'clock that afternoon, Beauregard looked across the Warrenton turnpike, which ran through the valley between the Confederates and the Federals, who occupied the higher elevation. He saw a column of troops moving toward his left and the Federals right. He was anxious to learn if they were his troops or the enemy's.

The swirling clouds of dust obscured them; their uniforms were similar; and their national colors were indistinguishable on that hot, sultry day with little or no wind to waft them.

Beauregard asked his officers to study the movement through their field glasses to see if they could identify the approaching army. They were finally identified as friendly forces, but during those agonizing moments of delay and indecision, some Confederate troops fired on their comrades approaching from the left.5

After it was learned that both Federal and Confederate troops wore badges of red flannel, officials of both armies accused their opponents of using the markings and colors of the other side as a military strategem.

Following the First Battle of Manassas, General Joseph E. Johnston, General G. W. Smith, General Beauregard, and other Confederate officers were determined that the fiasco at Manassas would not happen again.

Johnston, the ranking Confederate officer, ordered all military units to use the flags of their states. But only Virginia had supplied her troops with their state flag. The Confederate officers were then determined to design and adopt a battle flag that would be clearly recognizable.6

Beauregard Battle Flag

Beauregard, who had already anticipated the need for a new battle flag, wrote to William P. Miles, chairman of the House Military Affairs Committee of the Confederate Congress, suggesting the adoption of a new national flag. Failing in that effort, Beauregard asked his Louisiana officers to suggest some possible new designs for a battle flag.

When it became known that a new battle flag would soon be adopted, the high command was inundated with designs and drafts. Of the many different designs and configurations, the basic pattern that appeared most often was a cross, of various shapes, emblazoned with stars. The colors of red, white, and blue were also prominent.7

After lengthy consideration was given to various designs, Johnston and Quartermaster General William L. Cabell met with Beauregard at his headquarters in Virginia on September 1861 to finalize the design of the new battle flag. Johnston proposed a flag in the shape of an ellipse with a red field and a blue saltier (a diagonal cross, often called a St. Andrew's cross) containing a white star for each Confederate state.

Beauregard had suggested in his letter to Congressman Miles a square or rectangular design consisting of a blue field with a red cross containing gold stars. It appears from that correspondence that Beauregard favored either a Latin cross (a crucifix) or a Greek cross (St. George's), rather than the diagonal cross of St. Andrew.

Congressman Miles found Beauregard's color combination to be contrary to the laws of heraldry and suggested a blue saltier, with white stars, on a field of red. Deferring to Miles' knowledge of heraldry, Beauregard accepted his modifications and included them in his final proposal to Johnston and Cabell.8

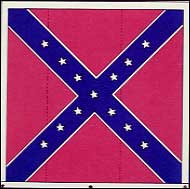

As the three Confederate officers were considering the design of the battle flag, Cabell indicated that Beauregard's design would be easier and quicker to produce than Johnston's and there would be no waste of cloth in a square or rectangular flag. Johnston, though he outranked Beauregard, accepted Beauregard's design and directed that the new battle flag be a perfect square. (figure 3)

The size of the flag was 4 x 4' for infantry, 3 x 3' for artillery, and 2 1/2 x 2 1/2' for cavalry.

General Bradley T. Johnson, whose Maryland regiment fought with the Confederacy at Manassas, had seen a watercolor drawing of the original design and described the flag several years later as a red square, on which was displayed a blue St. Andrew's cross, bordered with white, and charged with thirteen white, five-pointed stars. He referred to this design as Beauregard's battle flag.9

Both Johnston and Beauregard were anxious to have new flags prepared before the next military engagement. They cautioned Cabell to keep the design and shape of the new emblem a secret to prevent Federal forces from counterfeiting the flag and causing more confusion on the field of battle.

Johnston's hope for secrecy was dashed when he arranged for about seventy-five women in Richmond to begin making the new flags. The new design could be seen all over the Confederate capital the day after its adoption.

Beauregard and some other officers urged the Confederate Congress to adopt the new design as the national flag of the Confederacy, but the Congress declined to do so.

Cabell issued orders to quartermasters throughout the Army of the Potomac to provide the new battle flag to all their fighting units.

On October 1, 1861, the Confederate War Department authorized the use of the new battle flag by the Army of the Potomac, which was later renamed the Army of Northern Virginia by General Robert E. Lee.10

The war department did not direct other Confederate armies to adopt the new design although many of the Confederate armies east of the Mississippi River did eventually use the Beauregard flag.

When Beauregard assumed command of the Confederate forces in western Tennessee in early 1862, he found that General Leonidas K. Polk had already adopted a flag "similar to the one I had designed for the Army of the Potomac." Beauregard replaced Polk’s flag with his battle flag.

In September 1862, when Beauregard was reassigned to Charleston, he substituted the same banner for the state flags, then principally used in South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida.11

Although the Beauregard battle flag was perhaps the emblem most widely used by southern troops, it was never made the official battle flag of the Confederate Army and there were many other battle flags of varying styles, shapes, and colors used by Rebel forces during the Civil War.

Other Battle Flags

The variety of designs and shapes pictured in the collection of captured Confederate battle flags returned to southern states several years after the war, indicates that Confederate commanders exercised the option of designing and adopting their own flags. Most of the Arkansas battle flags pictured in the collection are blue. There were also rectangular variations of the Beauregard flag, as well as square flags with saltiers of varying widths with different configurations and numbers of stars.

The 40th Mississippi Volunteer Infantry Regiment adopted one of the most unusual of all the Confederate battle flags. The regiment's rectangular flag was a field of red, bordered in yellow, with thirteen white five-pointed stars and a white crescent. (figure 4)

The first regimental flag of the 11th Mississippi Infantry was a Stars and Bars with the stars in the canton arranged in the shape of a Latin cross. After its assignment to the Army of Northern Virginia, the regiment adopted the Beauregard design.12

The Beauregard battle flag was very popular among the rank-and-file soldiers and among the people generally. It was eventually adopted in rectangular form as the naval jack by the Confederate Navy on May 26, 1863. A naval jack is a small flag displayed on a ship's bow to designate the vessel's nationality.13

Second and Third National Flags

In 1863, the issue of a new national flag resurfaced in the southern press and in the Confederate Congress. There was increasing sentiment among the general public to replace the Stars and Bars.

In the spring of 1863, the Confederate Congress took up the issue of a new national flag. Although the editor of Richmond's Southern Illustrated News on March 12, 1863, chastised the Confederate Congress for wasting its time discussing the shapes and colors of flags while the war was raging and the southern economy was in disorder, he did admit that he detested the Stars and Bars because it resembled the Stars and Stripes.14

The strong emotions generated by the Confederacy's icons, especially its flag, sparked a controversy which produced a wave of letters to the editors of southern newspapers. One writer to the Southern Illustrated News objected to any change in the national colors. He had favored the adoption of the Stars and Stripes by the Confederacy back in 1861. If there had to be a change, however, he recommended the incorporation of the Beauregard battle flag in the new national flag.

The Richmond newspaper explained to its readers the difficulty in identifying and recognizing the Stars and Bars at great distances, and endorsed a new design.15

After an extended controversy over the incorporation of the Beauregard battle flag in the canton corner, the Congress adopted the second national flag of the Confederate States of America on May 1, 1863.

The new flag was a white field, its length double its width, with the Beauregard battle flag in the canton corner. One of the first prominent public displays of the second national flag was at the funeral of General Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson. The new flag draped his coffin and soon became known as the Stainless Banner.16

The second national flag had hardly been adopted before objections were raised about both its design and its shape. To some critics, it looked like a flag of surrender; others said it looked like a “big table cloth.” The Confederate Navy also complained that it was easily soiled, especially on the new steam vessels which the Confederacy had recently secured.17

And, the new national flag did not fly properly because of its shape and dimensions. To fly properly, the length of a flag should be no more than two thirds its width, rather than double its width as was the case with the second national flag.

The flag that flew over the Confederate capitol in Richmond did not conform to the dimensions specified in the statute of May 1, 1863. That flag had been modified to conform to the length “two thirds the width” specifications which allowed the flag to wave more gracefully.18

A design for another national flag, the third during the four-year history of the Confederacy, was being considered as early as the fall of 1864.

The designer of the new flag and the prime mover in its adoption was Major Arthur L. Rogers who had been seriously wounded at Chancellorsville in May 1863. Rogers sent drafts of the flag to several naval and army officers, including Robert E. Lee, asking for their suggestions and comments.

The Rogers design slightly modified the second national flag. To the second national flag, Rogers added a broad red perpendicular bar on the fly end. The dimensions of the third national flag would be length two thirds the width. The Confederate Congress adopted the third national flag on March 4, 1865, just over a month before Lee's surrender at Appomattox.

It is unlikely that the third national flag ever flew over any Confederate troops or civilian agencies. In a brief sketch of the flags of the Confederacy, General Bradley T. Johnson wrote: “I never saw this flag, nor have I seen a man who did see it.”19

Symbols and Memory

In the collective memory of White southerners, the failure of their forebears to win the independence of the Confederate States of America is known as the Lost Cause, and the Beauregard battle flag is the most enduring symbol of that cause. In the receding memories of the Confederate veterans, who adopted it as their official insignia, the battle flag was the soldier's banner, not the colors of the Confederacy.

There were no lobbyists stealing through the corridors of the capitol urging its adoption. Born in battle and bravery, it was the banner that rallied their comrades during the fearsome disarray of combat, when men were disoriented, and death was all about. The veterans, and their sons and grandsons, hoped that the battle flag could escape the bitterness and controversy attached to secession and Civil War.

To African Americans and many White people, the Beauregard battle flag is also a symbol of the Lost Cause and a reminder that Black freedom was won only because the cause was lost. The flag was the emblem of slavery carried by soldiers in a war to maintain it, and the icon of hooded night riders who terrorized and firebombed African Americans in the name of White supremacy.

In 1880, in another lost cause, Carlton McCarthy wrote a brief history of the Beauregard battle flag and advanced this explanation of its origin and expressed this hope for its future:

“It was not the flag of the Confederacy, but simply the banner—the battle flag—of the Confederate soldier. As such it should not share in the condemnation which our cause received, or suffer from its downfall…

This article is penned to accomplish, if possible, two things: first to preserve the little history connected with the origin of the flag; and second, to place the battle flag in a place of security, as it were, separated from all the political significance which attached to the Confederate flag and depending for its future place solely upon the deeds of the armies which bore it amid hardships untold to many victories.”20

But history has not placed the battle flag in a safe or secure place, above or beyond the enduring legacy of slavery and suppression, of insurrection and disunion.

Incorporated into Mississippi's state flag in 1894, the Beauregard battle flag has been swept up in the passions of modern politics and racial discord and is now, in 2000, the focus of an intense public discourse.

Note: Mississippi retired the state flag with the Beauregard battle flag in 2020, twenty years after this article was published, and replaced it with the "In God We Trust" state flag.

David G. Sansing, Ph.D., is professor emeritus of history, University of Mississippi. This article was updated in September 2021.

End Notes – History of the Confederate Flags

1. For the best one-volume history of the American Civil War, see James McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom (Ballantine Books, 1989); for a more extensive history, see Shelby Foote's three-volume study, Civil War, A Narrative (Vintage Books Edition, 1986). Details on secession and Civil War in Mississippi may be found in William Barney, The Secession Impulse: Alabama and Mississippi (Princeton University Press, 1974); Percy L. Rainwater, Mississippi, Storm Center of Secession (Otto Claitor, Baton Rouge, 1938); John K. Bettersworth, Confederate Mississippi (Louisiana State University Press, 1943); and Edwin C. Bearss, “The Armed Conflict, 1861-1865,” Vol. 1, 447-492, in Richard A. McLemore, (ed) A History of Mississippi (University Press of Mississippi, 1973)

2. On Brooke's resolution, see E. Merton Coulter, “The Flags of the Confederacy,” Georgia Historical Quarterly, vol. 37 (1953), 187-199, and Southern Historical Society Papers, vol. 38 (1910), 251-252; for details on the adoption of various Confederate flags see Devereaux D. Cannon, Jr., The Flags of the Confederacy, An Illustrated History (St. Lukes Press, 1988); Howard M. Madaus and Robert D. Needham, The Battle Flags of the Confederate Army of the Tennessee (Milwaukee Public Museum, 1976); Mrs. Lucile Lange Dufner, “The Flags of the Confederate States of America,” (MA Thesis, University of Texas, 1944); Richard Rollins, (ed.), The Returned Battle Flags (Rank and File Publications, Redondo Beach, CA edition, 1995); and Alan K. Sumrall, Battle Flags of Texans in the Confederacy (Eakin Press, Austin, Texas, 1995); for a study of flags in American history, see Whitney Smith, The Flag Book of the United States (William Morrow & Co., 1970) and Flags Through the Ages and Across the World (McGraw-Hill, 1975)

3. Southern Historical Society Papers (cited hereafter as SHSP, volume number, date for the first entry, and page number), 38, 253-256; E. Merton Coulter, The Confederate States of America, 1861-1865 (LSU Press, 1950), 117-119

4. SHSP, 38, 256

5. SHSP, 31 (1903), 68-70; SHSP, 8 (1880), 497-498

6. SHSP, 38, 258-259

7. SHSP, 38, 259-260; SHSP, 8, 498-499

8. SHSP, 38, 259-260; SHSP, 31, 69-70

9. SHSP, 24 (1896), 117

10. Coulter, Confederate States, 118; SHSP, 8, 155-156, 499; SHSP, 24 (1896), 117

11. SHSP 38, 260

12. For many illustrations, see Rollins, Returned Flags, Madaus and Needham, Battle Flags, and Sumrall, Battle Flags of Texans

13. Cannon, Flags of the Confederacy, 69

14. SHSP, 8, 156

15. Ibid

16. Cannon, Flags of the Confederacy, 19

17. Ibid, 19-22

18. Ibid, 22-24

19. SHSP, 24, 118; Bradley did note that Colonel Lewis Euker claimed to have seen a representation of the flag in December 1864, three months before its adoption.

20. SHSP, 8, 497-498