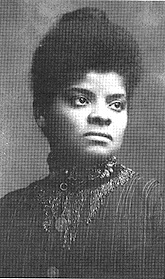

Ida Bell Wells (1862-1931), one of the most important civil rights advocates of the 19th century, was born in Holly Springs, Mississippi, just before the Emancipation Proclamation was signed. She was the first child of James Wells, an apprentice carpenter, and Elizabeth Warrenton, a cook.

A wartime birth in Mississippi

When Ida was born, both of her parents were enslaved and worked on the property of Spires Bolling, a building contractor. The family witnessed more than a dozen major military skirmishes during the Civil War before Confederate Mississippi surrendered in 1865 and the enslaved people were freed. Over 450,000 emancipated African Americans in the State of Mississippi had to look for jobs. Many also had to struggle to define new relationships with former owners who needed workers.

James Wells' owner in Tippah County was also his father. Shortly before he died, James's father apprenticed his eighteen-year-old son to learn the building trades from Spires Bolling. After emancipation, Bolling invited James to continue working for him. Wells became a skilled building craftsman, helping to repair and rebuild Holly Springs after the war.

James and his wife quickly exercised the privileges of freedom. They legalized their marriage, and as their family grew they deepened their commitment to education as a way out of poverty. James Wells served on the board of trustees of the newly organized Rust College (then called Shaw University). The couple eventually had four boys and four girls.

Ida Wells later wrote, “Our job was to go to school and learn all we could.”

When Ida Wells was sixteen both of her parents and her infant brother died in the Yellow Fever Epidemic of l878, a plague that killed over three hundred people in Holly Springs. Ida Wells took on the task of rearing her five remaining brothers and sisters (another brother had died earlier of spinal meningitis).

Ida get a job teaching in a rural school and with her family's savings, attended Rust College. Although she was expelled two years later after a confrontation with the school president, she continued to teach in local schools for three years.

A teacher in Tennessee

When her brothers were settled into apprenticeships in carpentry, Ida took her sisters and moved to Memphis to live with her aunt. While she waited to take the examination for teaching in the public schools of Memphis, she accepted a job in Woodstock, a rural community outside Memphis.

An important incident occurred on a train trip from Memphis to Woodstock. This dramatic event showed the different path her life would take.

Some eighty years before Rosa Parks refused to move to the back of a bus in Montgomery, Alabama, twenty-two-year-old Wells refused to move out of her train seat for which she had paid. She had bought a ticket for the first-class ladies' car and refused the conductor's order to move to the smoker car. The authorities forcibly removed her from the train.

Backed by the Civil Rights Act of 1875, she filed and won a lawsuit against the Chesapeake and Ohio Railroad in 1887. She was awarded $500 damage, but the Tennessee Supreme Court shortly reversed the victory. Frustrated, she began writing political columns in church newspapers. Having secured a job in the Memphis public schools, she saved her money and became part owner of a small newspaper called Free Speech and Headlight in Memphis.

In 1891 she was dismissed from the Memphis school system for a strong article she wrote pointing out unequal funding of the Black schools by the board of education.

For the rest of her life she would be an outspoken and courageous voice for civil rights, fighting educational inequities, lynching, and segregation, and supporting economic boycotts and women's rights.

Political journalist to the world

A violent episode close to home intensified her attention on the problem of violence toward Black people. Three of her friends in Memphis were lynched in 1892. They had defended their small grocery store against whites who attempted to put them out of business. When a deputy sheriff was killed by one of the three men, all were arrested and subsequently dragged from the jail by a mob and lynched.

The incident galvanized the Black community and fired Wells's determination to fight back. Her newspaper office was destroyed because of her hard-hitting investigations. She advised her readers to abandon Memphis, and she moved to New York City. She joined the staff of the New York Age and continued to write exposés of lynchings in the South. She lectured in Europe for a time, and in 1893 she moved to Chicago.

Civil rights campaign in Chicago

In Chicago, Ida Wells first attacked the exclusion of Black people from the Chicago World's Fair, writing a pamphlet sponsored by Frederick Douglas and others. She continued her anti-lynching campaign and began to work tirelessly against segregation and for women's suffrage. She helped block the establishment of segregated schools in Chicago.

In 1895 in Chicago, she married attorney Ferdinand Lee Barnett who founded and edited the Chicago Conservator, the city's first Black newspaper. The couple had three children. Although Ida Wells-Barnett tried to retire from public life to raise her children, she soon returned to her campaign for equal rights. In 1906 she joined with William E. B. Dubois to promote the Niagara Movement, a group which advocated full civil rights for blacks. In 1909, Wells-Barnett helped form the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People.

She never obtained a position of leadership within the NAACP, perhaps because she opposed Booker T. Washington's moderate position that Black people focus on economic gains rather than social and political equality with White people. Or perhaps it was because at this time women did not have such power. She founded the Alpha Suffrage Club of Chicago, the first Black suffrage organization in 1913, and from l913-1916 worked as a probation officer in Chicago. The poet Langston Hughes said her activities in the field of social work laid the groundwork for the Urban League.

When she was sixty-eight, she ran for the Illinois legislature, one of the first black women in the nation to run for public office. A year later, in 1931, she died at the age of sixty-nine.

The Ida B. Wells legacy

Writings published in her lifetime include Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in All Its Phases (1893), The Reason Why the Colored American is Not in the World's Columbian Exposition (1893), A Red Record (1895), Mob Rule in New Orleans (1900), and numerous newspaper articles. She wrote an autobiography which was published nearly forty years after her death. Crusade for Justice: the Autobiography of Ida B. Wells (1970) was edited by her daughter, Alfreda M. Duster.

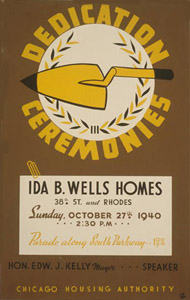

Her influence today is apparent. In 1941 the Chicago Housing Authority opened the Ida B. Wells Housing Project. High schools have been named for her from San Francisco, California, all across the United States to Jamaica, New York. A prestigious award for promoting Black people in journalism is named the Ida B. Wells Award. She was honored by the nation with the Ida B. Wells Commemorative Stamp issued in 1990. She was the subject of a prize-winning video, "Ida B. Wells: a Passion for Justice" produced by William Greaves in 1989.

In 1998, she was the subject of a new biography, To Keep the Waters Troubled: the Life of Ida B. Wells by Linda McMurry (New York, Oxford University Press). The Spires Bolling house in Holly Springs where she was born is now the Ida B. Wells-Barnett Family Art Gallery and open to the public.

Patti Carr Black, former director of the Old Capitol Museum, Mississippi Department of Archives and History, has written and edited numerous books.

Lesson Plan

Bibliography

Duster, Alfreda, ed. The Autobiography of Ida B. Wells (Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1970.)

McMurry, Linda, To Keep the Waters Troubled: the Life of Ida B. Wells (N.Y., Oxford University Press, 1998).

Royser, J. J. ed., Southern Horrors and Other Writings (Boston, St. Martin Press, 1997)

Smith, J. ed., Notable American Black Women (Detroit, Gale Research, 1992)