Growing Up in Kosciusko

Nestled on the Yockanookany River a little over an hour's drive from Jackson, Kosciusko, Mississippi, was home to James Howard Meredith, who grew up on his family’s 84-acre farm. Moses Meredith or “Captain”—James Meredith’s father— played a big role in his son’s life, and instilled pride and self-sufficiency in Meredith at a young age. Working on his family’s farm and dreaming of a world beyond Kosciusko, Meredith’s big dreams would ultimately change Mississippi and the nation.

Starting Activism at a Young Age

As the young Meredith grew into an independent and confident teenager, his dreams grew with him when he saw a picture of a White doctor as a football player at the University of Mississippi during a doctor’s visit. In that moment, Meredith knew that he wanted to attend the all-White University of Mississippi; however, an experience at age 15 in a segregated train caused him to “cry all the way home from Memphis.” This ride was Meredith’s first in a segregated train, so the young idealist could not understand the division between Black and White people of the South, having come from a close-knit yet sheltered upbringing under Moses Meredith. Although this incident affected Meredith, he persevered, serving as one of the first Black soldiers in the racially integrated U.S. armed forces from 1951 to 1960.

After being honorably discharged from the U.S. Air Force in 1960, Meredith focused his attention on uprooting White supremacy when he registered at historically Black Jackson State College, now Jackson State University. On the campus, he formed a secret society called the Mississippi Improvement Association of Students and left papers that called out White supremacy at the Governor’s Mansion and other politicians’ homes in a time when Black Mississippians could be murdered or beaten for defying White authority. Meredith wanted to challenge Mississippi’s segregated higher education system by registering at one of its biggest and oldest public universities—the University of Mississippi.

Enrolling at the University of Mississippi

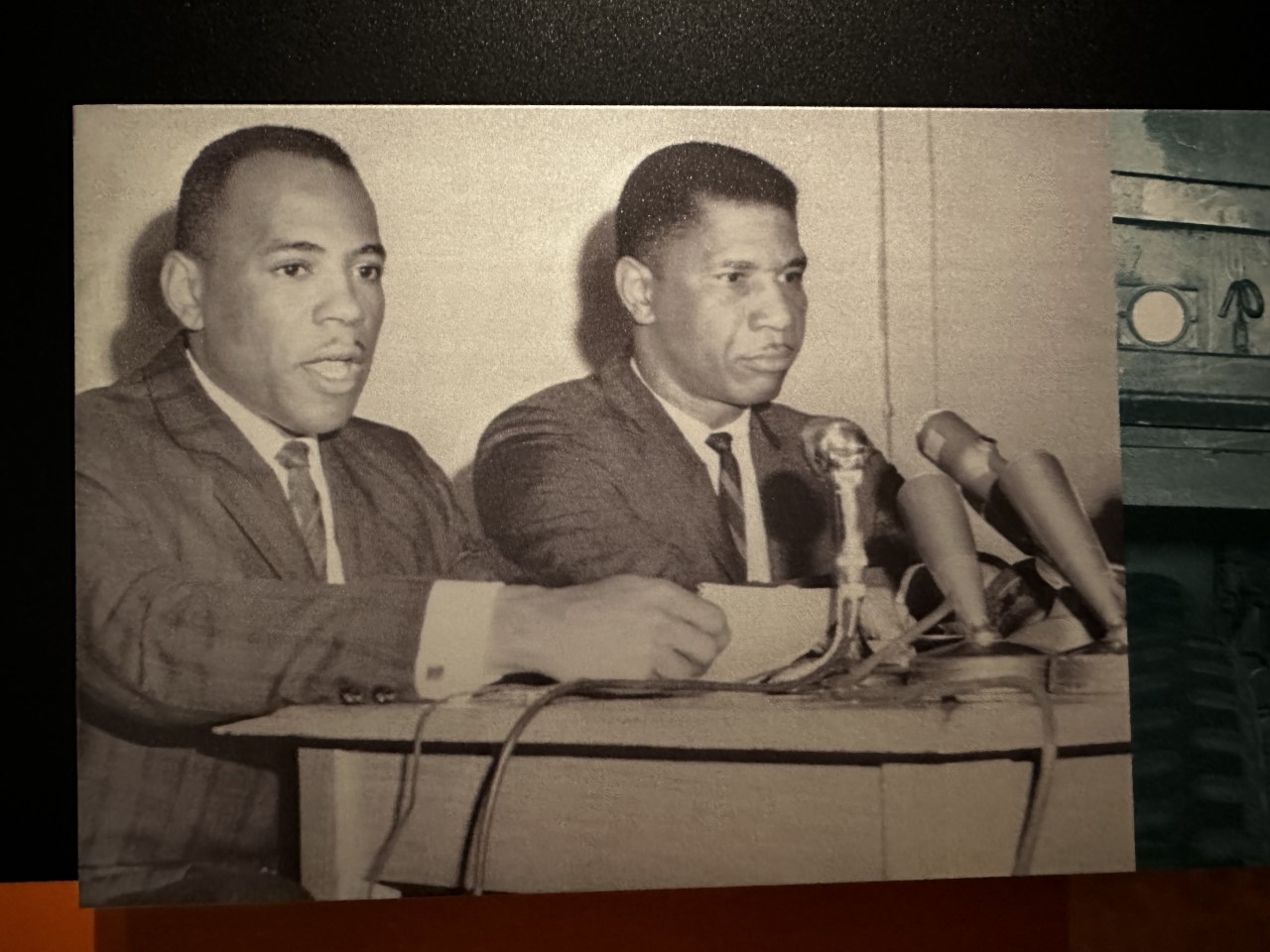

Applying to the University of Mississippi on January 20, 1961, Meredith was immediately rejected after writing in his application that he was a Black man. Unwavering in his mission to be admitted, he reached out to Medgar Evers, field secretary for National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). Working closely with Evers, the two young men mirrored each other in courage and boldness, and Meredith wrote to NAACP counsel Thurgood Marshall for legal help. Marshall assigned NAACP lawyers Constance Baker Motley and Jack Greenberg, and Meredith and his legal team worked together to gain admission.

The fight to attend the University of Mississippi took Meredith and his legal team all over Mississippi, where he appeared before several judges to argue that his admission to the public university was denied due to his skin color. At the same time, Rebel Underground—an anonymous, student-led newspaper at the University of Mississippi—printed papers promoting racial segregation while Mississippi governor Ross Barnett tried to stop Meredith’s admission. Although support poured in for Meredith from all over the world, resistance against his admission within the state was clear in articles that stated, “. . . Barnett is leading the state in this endeavor, and the state is unified behind him in this crusade as seldom as it has been united in any cause.” While he studied at Jackson State College, Meredith’s fight to attend the University of Mississippi lasted for sixteen months until the U.S. Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals took his case on June 15, 1962. Meredith’s case then went to the highest court in the land—the U.S. Supreme Court. On September 10, 1962, Supreme Court Justice Hugo Black granted Meredith admission to the University of Mississippi. However, another battle was brewing just around the corner.

The Battle at the University of Mississippi

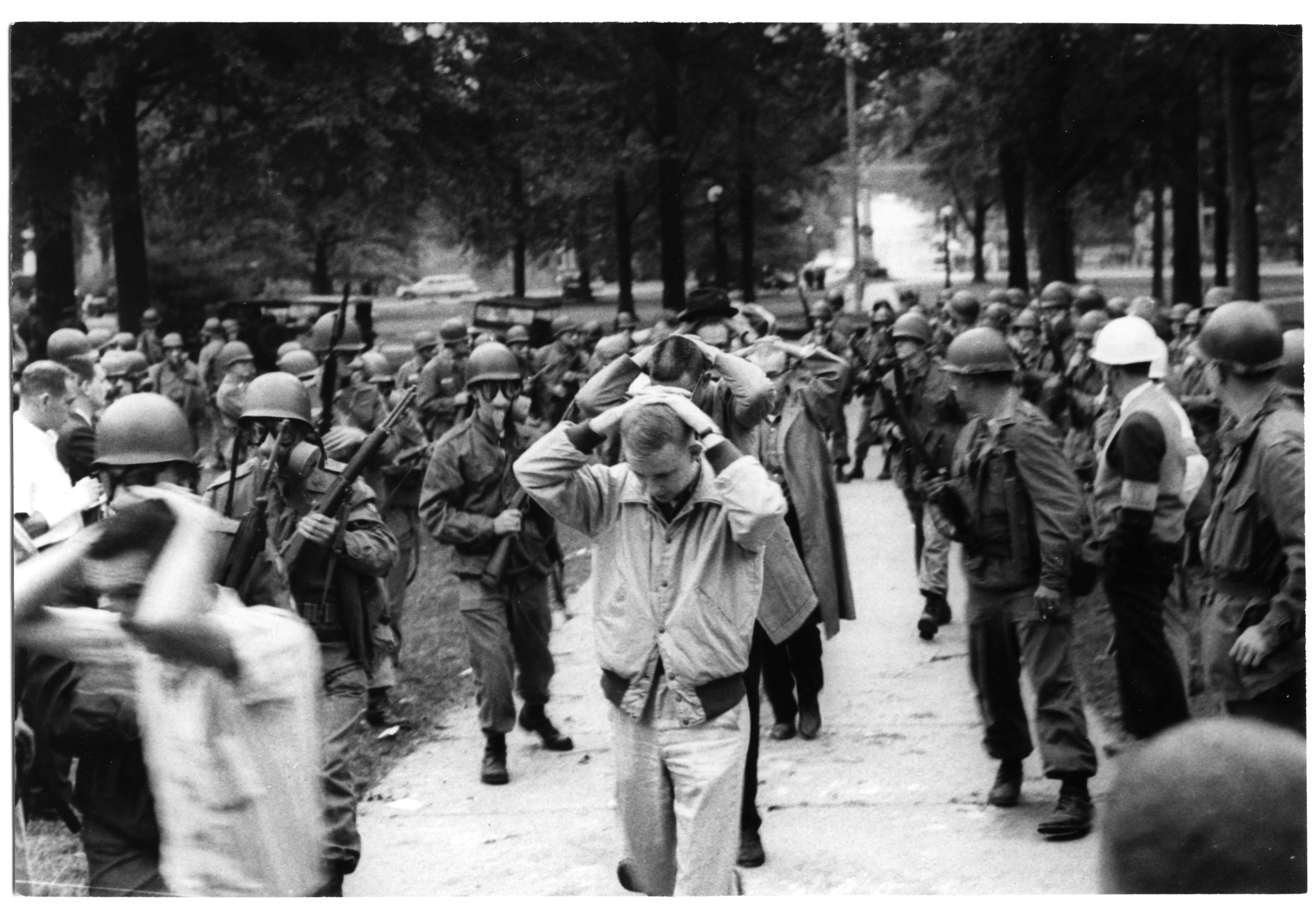

After blocking Meredith’s enrollment for weeks, Governor Barnett reached a deal with U.S. Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy on September 30, 1962, to allow Meredith to register for his classes. Even though the day had arrived that he would finally walk through the doors of the university he fought to attend, Meredith’s entrance would not come without marked violence on the campus. Guarded by U.S. Marshals sent by the Kennedy administration, Meredith was quickly moved into a room at Baxter Hall—a dorm on campus—for his own protection. Outside, a mob of angry White students had formed, and they attacked the U.S. Marshals, calling them “n-word” lovers and communists and demanding that they bring Meredith out.

While U.S. Marshals tried to contain the chaos, the mob escalated into a full-blown riot of more than 2,500 people, gathering both students and non-students. Rocks, pebbles, and lit cigarettes were thrown, and one U.S. Marshal shared that some students even threw “soft drinks filled with acid from the college chemistry laboratories.” The violence escalated to Molotov cocktails thrown to set vehicles on fire and damage to cameras, other media equipment, and journalists’ vehicles while Meredith remained inside as the battle raged on to fight his integration of the school. Sometime during the night, the rioting turned deadly when two people were murdered in the violence—French journalist Paul Guihard and an unnamed young Oxford man. Although Federal troops eventually arrived to stop the rioting, more than 200 people had already been injured. Governor Barnett tried to call for peace, but the damage had been done. Not only would the University of Mississippi never be the same, but the state of Mississippi had changed within only a few hours.

The Aftermath

On October 1, 1962, Meredith finally registered for his classes, but his presence at the University of Mississippi drew hostility from students. While some students refused to attend classes with Meredith, others left classes early, causing class sizes to shrink or be completely empty. Additionally, unlike his peers, U.S. Marshals escorted Meredith around campus to protect him from the threat of violence. Despite being separated from his peers and constantly guarded by U.S. Marshals, Meredith graduated with a bachelor’s degree in August 1963. He also went on to earn his LL.B degree from Columbia Law School in 1968.

What was once a dream born in Kosciusko became a hard-won battle that opened doors for James Meredith and for Black people across the nation. Although Meredith is remembered as a force in the Civil Rights Movement, his journey also conveys a universal struggle of perseverance and bravery in the face of extreme adversity. This aspect of his story is one that generations—both current and future—can use as inspiration to seek and enact justice, peace, and equality inside their communities and across the globe.

Candace Mckenzie is a public information officer at the Mississippi Department of Archives and History.

Lesson Plan

-

James Meredith with NAACP field secretary Medgar Evers. Photo courtesy of the Ed Meek Collection, University of Mississippi 1962. Joint ownership between Ed Meek, The University of Mississippi, The School of Journalism and New Media and The Department of Archives and Special Collections. -

James Meredith, center, an Air Force veteran suing the State of Mississippi for admission to the all-white University of Mississippi, leaves federal court in Jackson, Miss., in this Jan. 16, 1962, file photo, for a noon break with attorneys Derrick Bell, left, and Constance Baker Motley, both of New York. (AP/File Photo)

-

Detained students with hands on head walk towards Lyceum. Copyright of the Ed Meek Collection at the University of Mississippi: Integration of 1962. Joint ownership between Ed Meek, The University of Mississippi, The School of Journalism and New Media and The Department of Archives and Special Collections. -

James Meredith seated in a classroom. Copyright of the Ed Meek Collection at the University of Mississippi: Integration of 1962. Joint ownership between Ed Meek, The University of Mississippi, The School of Journalism and New Media and The Department of Archives and Special Collections. -

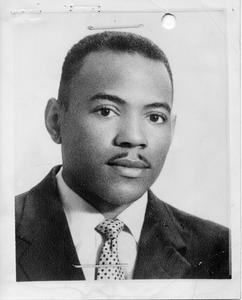

Mississippi State Sovereignty Commission Photo of James Meredith. Citation: Mississippi State Sovereignty Commission, "Mississippi State Sovereignty Commission Photograph," May 11, 1967, SCRID# 3-11-0-25-1-1-1-cph, Series 2515: Mississippi State Sovereignty Commission Records, 1994-2006, Mississippi Department of Archives and History, April 20, 2006.

Sources

“About James Meredith”. UM History of Integration. The University of Mississippi. Accessed November 21, 2022. https://50years.olemiss.edu/james-meredith/.

Doyle, William. An American Insurrection: The Battle of Oxford, Mississippi 1962. New York. Random House, Inc, 2001.

Goudsouzian, Aram. Man on a Mission: James Meredith and the Battle of Ole Miss. The University of Arkansas Press, 2022.

“James Meredith: American Civil Rights Activist and Author”. Encyclopedia Britannica. Accessed November 21, 2022. https://www.britannica.com/biography/James-Meredith.