Mississippi is properly famous as the home of the blues and of the first star of rock and roll. It is also the home of Jimmie Rodgers, described by many as “The Father of Country Music.” Rodgers had two other nicknames during his career, “The Singing Brakeman,” which referred to his work on trains, and “America’s Blue Yodeler,” which described one of his distinctive contributions to country music.

Publicity photographs also portrayed Rodgers as a guitar-playing cowboy and as a sharply dressed man-on-the-town. These various images of a musician who worked on trains, identified with cowboys, sang the blues, yodeled, and knew his way around modern towns and cities help illustrate the range of Rodgers’s musical interests.

The brakeman

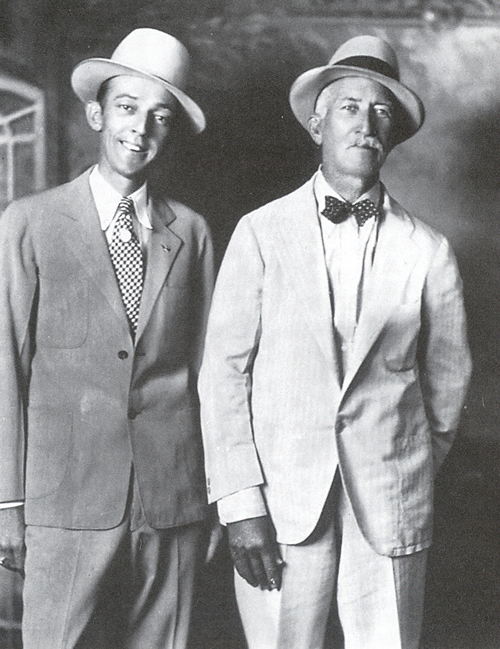

Jimmie Rodgers was born James Charles Rodgers outside Meridian, Mississippi, on September 8, 1897. Since his father, Aaron Rodgers, worked on the Mobile and Ohio Railroad, Jimmie Rodgers grew up traveling, especially after his mother, Eliza Rodgers, died when Jimmie was only five or six. From age fourteen until he was twenty-eight, he worked, sometimes irregularly, as a brakeman or flagman on railroads that took him through much of the South and Southwest.

Always interested in making music and seeing if he could make a living from it, Rodgers pursued music as a career only after he had to give up railroad work because of health problems. He contracted tuberculosis and discovered that railroad work made it hard for him to breathe. In 1924 Rodgers started singing in traveling shows, vaudeville shows, medicine shows, and various other productions. In 1927 he first performed on the radio in Asheville, North Carolina, and recorded his first songs in Bristol, Virginia. Although he made records for only six years, between 1927 and his death from tuberculosis in 1933, Rodgers recorded more than 100 songs.

The songs

His songs were about three minutes in length, and almost all featured Rodgers playing the guitar. Some songs had bands accompanying the singer, and others consisted entirely of Rodgers playing and singing. Part of Rodgers’s uniqueness lay in the variety of his music and part lay in his appealing voice which almost everyone liked.

Country music, sometimes called hillbilly music, emerged in the early 20th century as a self-consciously traditional, nostalgic music of rural white people in the American South, stretching from Appalachia to Texas. The term “country music” distinguished it from music associated with city people, whether that meant classical music and opera, or Broadway shows and the music of professional songwriters who wrote on so-called Tin Pan Alley in New York.

Many early country musicians knew a wide range of songs, but they adopted a rustic pose to satisfy a broad audience who wanted simple songs about simple life, especially the life on isolated mountaintops, on the free range of Texas, or, perhaps less often, the life on independent small farms. Many early country musicians tended to play, record, and identify themselves with the area from Nashville, Tennessee, to Atlanta, Georgia, to the mountain areas of eastern Tennessee and Kentucky, and to the western parts of the Carolinas and Virginia.

As a Mississippi native and as someone willing to play almost any form of music, Rodgers did not fit the mold of early country music. He did not idealize farm life, and rarely sang about mountains. Rather, through his music he portrayed himself as more of a man of the world. While most of his records were marketed as country or hillbilly music, he learned a great deal from the styles of Tin Pan Alley songs, the blues, and jazz. He performed a few songs with fellow country stars the Carter Family from Virginia, but he also made a recording with Louisiana jazz legend Louis Armstrong. In fact, jazz tubas and clarinets occasionally added surprising twists to Rodgers’s songs. A Hawaiian-themed song included ukuleles, and some Rodgers songs sounded more like fast-moving vaudeville tunes than conventional country songs.

Rodgers’s most notable musical innovation was a series of songs he called Blue Yodels. In his short career he recorded thirteen Blue Yodels. All are in the blues AAB format (saying a line twice and then following with a concluding line). His popular song, “T for Texas,” also called “Blue Yodel No. 1,” began with “T for Texas, T for Tennessee/T for Texas, T for Tennessee/T for Thelma, that woman made a fool out of me.” Blue Yodels were blues songs in style, sound, and lyrics. They generally told of serious trouble, sometimes of violence between men and women, and they rarely had nostalgic or happy endings. The narrator of “T for Texas” planned “to shoot poor Thelma/Just to see her jump and fall.”

Yodeling came from various sources, perhaps from cowboy songs or from the songs of travelers in the Swiss Alps. Rodgers was not the first musician to sing “Yo de lay hee-ho” between verses of his songs, but he made it such a trademark that some people assume country music had always included yodeling.

The lyrics

It is difficult to interpret the lyrics of popular songs as if musicians simply sang about their own experiences and ideas. Popular singers, then as now, tend to combine lyrics about their own experiences with notions of what audiences would like to hear. In some ways they are like autobiographers telling their own stories, while in other ways they are more like actors, playing different roles to entertain their audiences.

Rodgers co-wrote many of his songs, sometimes by reworking older songs, and often by writing a tune while another writer supplied the words. Sometimes he sang popular songs in his own musical style, but sometimes he was clearly singing about himself. For instance, he sang, “I had to quit railroading/It didn’t agree at all.” In another song, he asked, “Will there be any freight trains in heaven?” And when he sang “TB Blues,” and “My Time Ain’t Long,” his audience knew he was singing about his own illness.

Three themes dominated the lyrics of Rodgers’s songs. One was movement. His songs frequently discussed moving by trains or horses. Sometimes movement led back home, but sometimes it did not. A second theme was a sentimental picture of home life. Songs about love and longing for mothers and fathers were common, and Rodgers sang many tunes such as “Daddy and Home” and “Down the Old Road to Home.” A song called “A Drunkard’s Child” began with the child on the road, the mother dead, and the father drunk, all because “Daddy went to drinking.” Through the third theme, he performed numerous songs about failed love. Sometimes love failed because men or women left, or because they cheated, or even because they committed crimes and went to jail. People in Rodgers’s songs often spent time on chain gangs, or in the jailhouse, and they spent their time there lamenting the bad decisions that kept them away from the people they loved.

Throughout his travels and his illness, Rodgers kept up an image of a smiling, likable individual. He built up a large body of fans both through his likable stage performances and his numerous records. Along with the serious topics of many of his songs—illness, separation, violence, poverty, troubles of many kinds—he could be playful. In one of his early popular songs, “Peach Picking Time Down in Georgia,” he began with the image of everyone working hard, picking crops in different parts of the South, but ended by “pickin’” an attractive woman, with whom he hoped to pick a wedding ring. The multiple uses of “pickin’” was even more amusing because the term also referred to a guitarist “pickin” his instrument. Partly because of his ability to make play out of trouble, Rodgers became, in the words of historian Bill Malone, “the first country singing star.”

Two features of Mississippi life were especially important for Rodgers, who sang songs such as “Mississippi Moon” and “Mississippi Delta Blues.” First, working on trains gave him numerous stories about, and insights into, traveling people. In his songs, he empathized with people on the move, in large part because whether as a railroad worker or a traveling musician, he was one of them. This empathy was especially important in the 1930s during the Great Depression, when so many people had to travel in search of work. Songs like “Hobo’s Meditation” portrayed sad men riding the trains from the point of view of a sympathetic narrator who hopes their eventual destination of heaven would have no insulting people or “tough cops.” Second, as a Mississippian, Rodgers grew up hearing more African-American music than most early country musicians were likely to have heard. The Blue Yodels were unique among country songs in part because they followed the style of the blues.

Texas and tuberculosis

Like many blues musicians who moved to Chicago, and like Elvis Presley who moved to Tennessee, Rodgers spent his later years away from Mississippi. As a singer, Rodgers usually identified himself as a Texan. He spent his last few years in Texas because he believed the climate of southern Texas was especially healthy and because he enjoyed the image of a cowboy.

Rodgers knew his death was coming, and sang about it. Tuberculosis was a common killer in the early 20th century, and he was declining physically as he took a train to New York for what proved to be his final recording session for RCA Victor in 1933. At age 35, he was so weak that he had to rest on a cot between songs. He died at the Taft Hotel in New York on May 26, 1933, the night after the session, planning to make more records.

Jimmie Rodgers was extraordinarily popular in his short lifetime, and remains popular with generations of music fans. Numerous musicians have remade Rodgers’s songs, especially “T for Texas” and “In the Jailhouse Now,” and his influence has been wide. He was the first performer inducted into the Country Music Hall of Fame in 1961 and in 1976, the Jimmie Rodgers Memorial Museum opened in his home town of Meridian.

Ted Ownby, Ph.D., is professor of history and southern studies at the University of Mississippi. He is the author of American Dreams in Mississippi: Consumers, Poverty and Culture, 1830-1998 and of Subduing Satan: Religion, Recreation, and Manhood in the Rural South, 1865-1920.

Lesson Plan

-

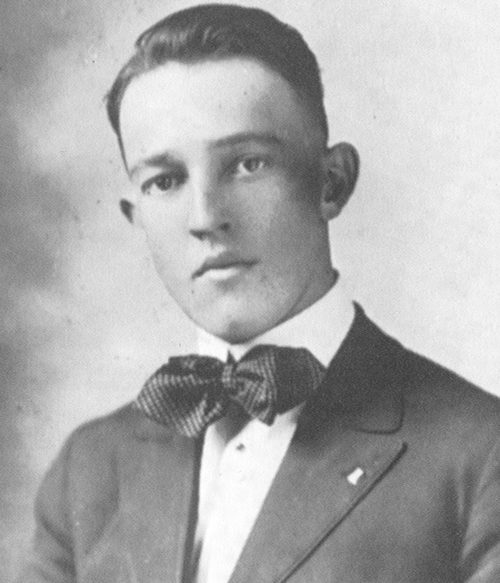

Jimmie Rodgers at age 19. Courtesy, Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum -

Jimmie with his father, Aaron Rodgers. Courtesy, Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum

-

Jimmie Rodgers in a movie still from “The Singing Brakeman,” a short film made in 1929 by Columbia-Victor Gems. Courtesy, Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum -

Jimmie Rodgers in one of his publicity poses, with his Weymann “Jimmie Rodgers Special” guitar. Courtesy, Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum -

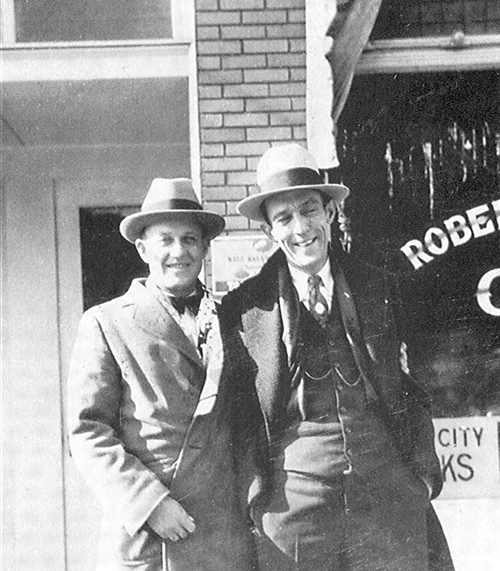

Jimmie Rodgers with fellow musician Clayton McMichen in Tupelo, Mississippi, in December 1929. Courtesy, Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum

References:

Malone, Bill C. Country Music U.S.A. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1985.

Malone, Bill C. Don’t Get above Your Raisin’: Country Music and the Southern Working Class. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2002.

Porterfield, Nolan. Jimmie Rodgers: The Life and Times of America’s Blue Yodeler. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1991.

Ivey, William. Notes to This is Jimmie Rodgers. RCA Records, VPS-6091(e), 1973.