Man-made ice is a common everyday item, one that Americans take for granted. It is produced as small cubes in refrigerators at homes and businesses, and fills ice chests at parks and beaches for use whenever we need or want it.

Not too long ago, however, people had to order block ice from their local ice plant and have it delivered to their homes and businesses. Indeed, the making of block ice was an integral part of the business community throughout Mississippi and the delivery of it by the “iceman” contributed greatly to daily life for Mississippians for nearly a hundred years.

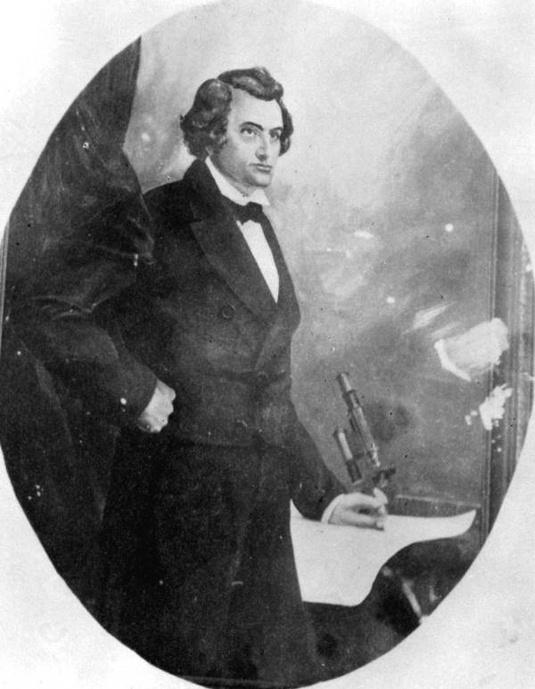

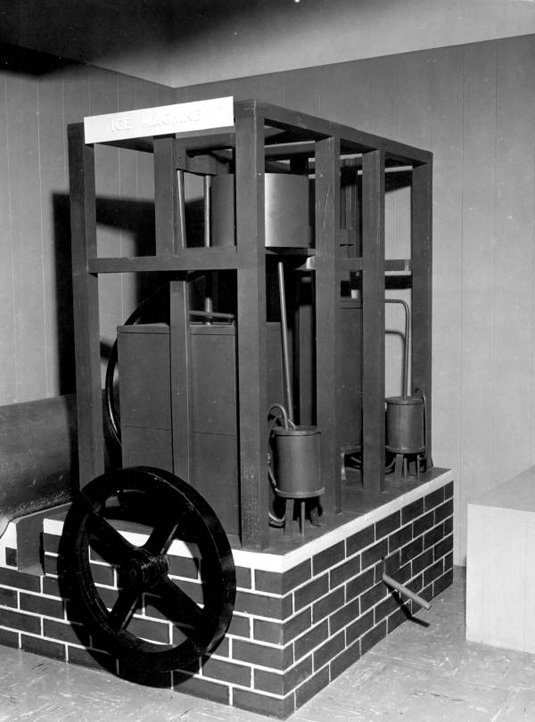

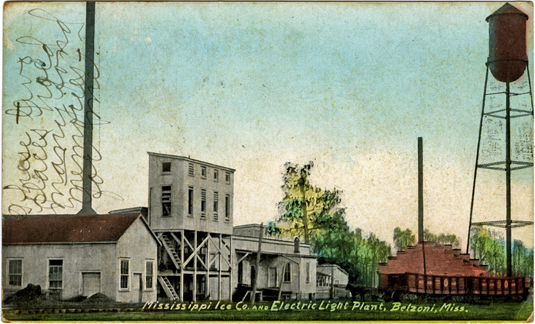

Man-made ice was the world’s first means of artificial cooling. This brand new concept, that humans could produce cold, was a far-fetched idea for people in the mid-19th century. Floridian John Gorrie, M.D., (1803-1855) was granted the first U. S. Patent (No. 8080) for mechanical refrigeration in 1851 for his invention of the first ice machine in 1845. Gorrie is considered the father of air conditioning and mechanical refrigeration, yet he was ridiculed during his lifetime. It wasn’t until 1868 that the world’s first commercial ice plant opened in New Orleans, Louisiana. The first ice plant in Mississippi was built in Natchez in the late 1870s and the second plant in the state was the Morris Ice Company, which opened in Jackson in 1880.

Natural ice

Manufactured ice was often called “artificial” ice to distinguish it from the natural ice that people in urban centers were familiar with. Frederic Tudor (1783-1864) of Boston began the North American natural ice trade in 1805. Harvesting ice in the winter from the frozen lakes, ponds, and rivers in the north, and storing it in icehouses through the summer, he started shipping natural ice south. By 1847, nearly 52,000 tons of natural ice traveled by ship or train to twenty-eight cities across the United States. Although ice blocks were stacked within wood shavings and sawdust for shipping, the ice began its meltdown enroute and was greatly reduced in weight before it was unloaded at its destination. Harvested natural ice was a known, yet luxurious, commodity.

Thus, whenever people heard the news about artificial ice they were astonished, and some simply could not believe it was true. There is a story about a country preacher in 1902 who visited an ice plant in Jackson, seeing for himself that humans were making ice. Upon sharing this news with his congregation when he returned home, the good people of his faith decided either the preacher had lost his mind or had been taken in by the devil himself. They kindly asked him to step down from his post for making such an outlandish statement that ice could be made in Mississippi in July.

Manufactured ice

By the 1910s, however, people had discovered the numerous uses for manufactured ice and plants sprang up all across the nation. Ice plants were sprawling buildings with an engine room, a tank room, and a storage room for the ice. Most ice plants produced 300-pound blocks, approximately four feet by two feet by one foot. It took up to three days to make a clear block of ice, the goal of most icemen because clear ice is denser and lasts longer than foggy ice. To produce a clear block of ice, the water must be kept in motion as it freezes so the air bubbles escape. Impurities in the water freeze at a slower rate than the water so the iceman would remove the water in the center just before it froze and replace it with distilled water, making the ice cleaner than the water used to produce it.

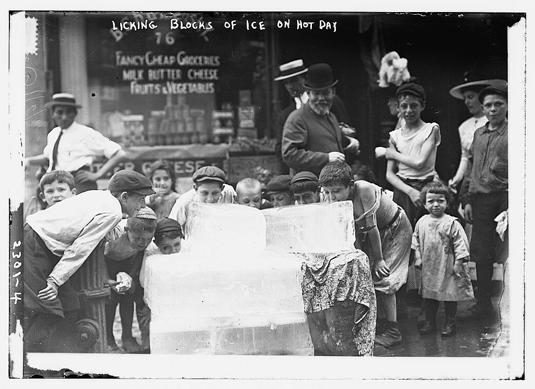

Once made, block ice was delivered to homes and commercial businesses, originally by mule and wagon, then later by automobiles and trucks. The mules learned the delivery routes so well they didn’t need a driver. Instead, the iceman stayed in the back of the wagon, hopping out when the mule stopped at the right location. The homeowner would place a card in the window showing how many pounds of ice were needed that day. The iceman would use an ice pick to chop off the desired amount of ice, normally 25, 50, 75, or 100 pounds. Using tongs he would hoist the block onto his back and carry the ice to the house and put it in an icebox, a household appliance developed in 1861. In the summertime, children would run behind the deliveryman begging for a sliver of ice, the only cool thing available because there was no air conditioning.

Mrs. A.C. Arenz, the wife of an ice plant manager in Friars Point, Mississippi, recalls a story about an ice deliveryman who called in sick for work one day, but volunteered his son to cover his delivery route. The young man dutifully went to the factory, got a load of ice, and delivered the blocks to all his dad’s customers. When he returned to the plant, he learned a regular customer had called, asking for her ice. The lad told Mr. Arenz he had delivered her ice. “Well,” Arenz said, “She can’t find it and she says she didn’t get any ice. Let’s go back over to her house and you show her where the ice is.” Turns out, the young man had indeed given the woman a block of ice and it was sitting right where he had left it: not in the curious new item called an icebox, but in a similarly shaped item, the woman’s oven. Although iceboxes came in many shapes and styles, from basic oak boxes to fancy claw-footed boxes with seaweed and tin for insulation, most likely the young man’s family did not own one and kept their ice by digging a hole in the ground, adding sawdust for insulation, and then storing the block ice in the hole.

Ice is boom to business

By 1920, the manufactured ice industry added close to $1 billion a year to the income of the people of the United States, and it ranked ninth in the amount of investment among American commercial enterprises. According to the 1920 U. S. Census Bureau, 4,800 block ice plants employed 160,000 people and produced 40 million tons of ice in 1920 — or nearly 750,000 blocks of ice every twenty-four hours.

With the advent of inexpensive manufactured block ice, new businesses could operate year round in Mississippi, while others moved to the state for the first time. Dairy farming, concrete production, chicken processing plants, bakeries, and florists are a few types of industries that prospered using manufactured block ice. Two industries in particular, farm produce and seafood, grew hand-in-hand with the rise of manufactured block ice.

Most farm produce had been a local commodity before block ice, spoiling too quickly to be shipped long distances. But by putting block ice in baffles on either end of a rail car, and for hardy produce such as cabbage, spraying chopped ice directly on top of the produce, railroads could haul produce greater distances. Because of inexpensive block ice, local items became regional foods and then national foods. As a result, production of fruits and vegetables rose faster in the South than the increase in population between 1890 and 1920. Shipping the bounty of the warm sub-tropical climates of the South to northern and mid-western markets helped eliminate the national health problem of scurvy.

The McComb Ice House and Creamery, in McComb, Mississippi, located in the crossroads of the strawberry, tomato, and bean produce markets of Mississippi and Louisiana, became the largest ice house in the South in 1924, producing 200 tons of ice a day. In 1926, it was the largest railroad-icing complex in the world, icing an entire trainload of cars in less than an hour, half the usual time.

The seafood industry along the Mississippi Gulf Coast flourished with the use of block ice. Chipped block ice was blown into the ship hull, enabling fishermen to stay out for one or two weeks at a time. Seafood markets kept the catch cold on a bed of crushed ice. Railroad cars used ice to keep the seafood fresh during transit. Finally, the seafood was stored in the family icebox that used still more block ice. With such demand for ice, block plants along the Gulf Coast were very prosperous, including Pascagoula Ice and Freezer Company, the only block ice plant still operating in the state in the 21st century (Note: while true when the article was published, as of 2021, the Pascagoula Ice and Freezer Company has permanently closed).

At a regional convention in 1922, Southern Ice Exchange President S. C. Oliver observed that part of the ability of American cities to grow so rapidly in population during the 20th century was “due to the dependable supply of farm products, since without iced refrigerator cars, the great cities would starve.” Ice was so vital to the nation a man could be excused from war duty during both World War I and World War II if he worked at an ice plant.

New inventions, such as electric refrigerators, room air conditioners, and overland transportation cooling systems slowly replaced the need for block ice. By the 1960s few block plants remained, dwindling down to about fifty plants nationwide by the early 21st century. Most remaining block ice plants are in the South, finding niches in produce, sculpture, and the movie industry. To most people, manufactured ice now refers to packaged ice, the kind sold at convenience stores or used in restaurants.

For almost one hundred years, block ice provided health, comfort, and convenience for Mississippi’s people and business community. The making of block ice was a preeminent industry that shaped the culture and economy of Mississippi.

Elli Morris is a freelance photojournalist and the author of Cooling the South: The Block Ice Era, 1875-1975. She is the great-granddaughter of the founder of Morris Ice Company, which opened in 1880 in Jackson, Mississippi.

Lesson Plan

-

300-pound blocks of manufactured ice. Photograph by Elli Morris. Used by permission. -

Dr. John Gorrie (1803-1855) received the first U. S. patent for mechanical refrigeration. Courtesy State Library and Archives of Florida, Florida Photographic Collection, RC12666.

-

Model of first ice machine on display at the John Gorrie Museum in Apalachicola, Florida. Courtesy State Library and Archives of Florida, Florida Photographic Collection, CO27422. -

Ice wagon making deliveries, circa 1899 or 1900. Courtesy Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, LC-DIG-ppmsca-08776. -

Licking blocks of ice on a hot day. Image created between circa 1910 and 1915. Courtesy Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, LC-B2-2301-4. -

Morris Ice Company in Jackson, Mississippi, circa 1927. Courtesy Elli Morris. -

Mississippi Ice Co. and Electric Light Plant in Belzoni, Mississippi. Courtesy Mississippi Department of Archives and History, Forrest Lamar Cooper Postcard Collection, PI/1992,0001. -

1945 Dodge ice delivery truck for the Hazlehurst Ice Company, Hazlehurst, Mississippi. Photograph by Elli Morris. Used by permission. -

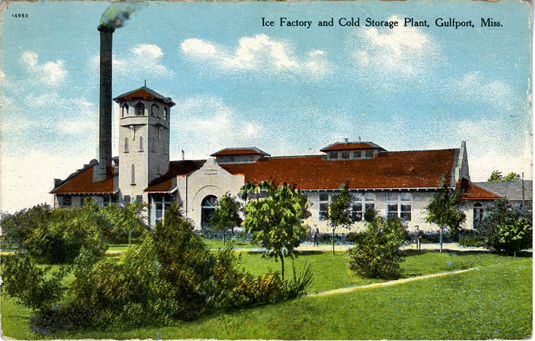

Ice factory and cold storage plant in Gulfport, Mississippi. Courtesy Mississippi Department of Archives and History, Forrest Lamar Cooper Postcard Collection, PI/1992.0001. -

Engine room at the Pascagoula Ice and Freezer Company on the Mississippi Gulf Coast. Leather-belted fly wheels are 10-feet high. Photograph by Elli Morris. Used by permission.

References

Arenz, Katherine. Interview by author. Friar’s Point, Mississippi, 14 April 2004.

Chapel, George L. “Dr. John Gorrie Refrigeration Pioneer.” Apalachicola, Fl: Apalachicola Area Historical Society, Inc.

Hirshberg, Leonard Keene. “The Value of Ice.” Refrigeration 27.2 (1920): 22.

Oliver, S. C. Address to the Southern Ice Exchange Convention. New Orleans. 27 November 1922, Refrigeration 31.5 (1922): 34.

“McComb Ice House and Creamery Timeline,” Plaque on wall of The Ice House, McComb, Mississippi.

“Statement of Significance for Kramertown-Railroad Historic District Nomination.” Mississippi Department of Archives and History, 1980. Originally published by Jack Hancock. “Spotlight on McComb – a City That Was Built on Purpose.” Jackson, [Miss.] Daily News 31 July 1949.

Suggested Reading

Becker, Raymond B. John Gorrie, M. D.: Father of Air Conditioning and Mechanical Refrigeration. New York: Carlton Press, 1972.

Krasner-Khait, Barbara. The Impact of Refrigeration History Magazine. 14 March 2004.

Morris, Elli. Cooling the South: The Block Ice Era, 1875-1975. Richmond: Wackophoto, 2008.

Nagengast, Bernard. It’s a Cool Story! Mechanical Engineering Magazine Online. American Society of Mechanical Engineers. 14 March 2004

Sherlock, V. M. The Fever Man: A Biography of Dr. John Gorrie. St. Charles: Medallion Press, 1982.