Any reference to art in Mississippi and the South since the early part of the 20th century would not be complete without Marie Hull. Her art and life as a painter and teacher have influenced hundreds of young artists to make their way in art.

From the 1975 Marie Hull Exhibit brochure

Marie Atkinson made the discovery at the age of twenty, that she “wanted to paint more than anything else.”

She was born in Summit, Mississippi, on September 28, 1890. Her parents, Ernest Sidney and Mary Katherine Atkinson, loved music and introduced Marie to music at an early age. When she was only age four, her parents took her to a concert by composer and pianist Jan Paderewski in New Orleans. Marie was moved by the music and her parents later encouraged her to take piano lessons. All through high school, she practiced piano four to five hours each day. She learned discipline with this schedule, but found little joy.

No drawing or art appreciation classes were offered at her elementary and high schools — art classes were not compulsory in Mississippi public schools then. Nor did her parents provide private art lessons for her. Consequently, she did not know for a long time that she had extraordinary artistic talent.

In 1909, she took a degree in music from Belhaven College in Jackson, Mississippi. After graduation, she began what was an acceptable career for a woman at the turn of the 20th century — she offered private piano lessons and played the pipe organ for churches.

A year later, artist Aileen Phillips moved to Jackson and Marie began taking art lessons from her. Phillips had studied at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia, the first and finest art school in the country at the time, and was the only trained art teacher in Jackson. The year of Marie’s first art lessons, 1910, was also the year that the first Mississippi public school — Central High School in Jackson — included art in its curriculum.

The artist as student

When Marie began art lessons from Phillips, her intentions to continue her music career flew out the window, for suddenly she knew that painting was her talent and her passion. She became a member of the fledgling art community in Jackson, specifically the newly formed Mississippi Art Association, which had evolved in 1911 from an art study group organized in 1903 by Bessie Cary Lemly. The Mississippi Art Association was composed of artists and its primary focus was the annual juried art exhibition at the Mississippi State Fair. Indeed, it was Marie who suggested in 1912 that the association begin a collection of paintings by establishing the first prize in the annual state fair exhibit as a purchase award. The association’s collection would later become the foundation of the Mississippi Museum of Art. The first canvas the association acquired was William P. Silva’s The Shower.

Marie’s art teacher would soon move away from Jackson but at Phillips’ encouragement — and over the objections of her parents — Marie enrolled at the Pennsylvania Academy, a move at the time considered so daring she had to take her mother along as chaperone until she was settled with a family that boarded and chaperoned young women.

After a year at the academy, Marie returned to Jackson in 1913 and began teaching art at Hillman College, a girls’ school that later merged with Mississippi College in Clinton. She soon left Jackson again to study at the Art Students’ League in New York. Returning to Jackson, Atkinson taught piano and worked as a commercial artist, illustrating books and magazines. In addition, remembering her own lack of art lessons as a child and how long it took her to discover her talent, she was eager to teach art to children. She gave art lessons in her home to a small group of private students and, through the Mississippi Art Association, sponsored workshops for African American children at the College Park Clubhouse in Jackson.

In 1917, Marie married Emmett Johnston Hull, a Jackson architect. It was a good match. Marie made architectural renderings for him, and he encouraged her painting. They traveled extensively across the United States and found it a good way for her to study landscapes and for him to study architecture.

The artist as traveler

Marie Hull was awarded her first gold medal from the Mississippi Art Association in 1920 and, in 1926, she received her first prize at the Southern States Art League.

She had an insatiable desire to learn and traveled all over the country to study under some of America’s best artists: David Barber and Hugh Breckinridge at the Pennsylvania Academy; John Carlson and Robert Reid at Colorado Springs Art Center; Frank Vincent Dumond at the Art Students’ League in New York; and Robert W. Vonnoh in Connecticut. From them she learned everything from landscape to color to anatomy.

In 1929, a big break came when she won the second purchase award for her still life of Yucca blossoms for the Texas Wild Flower Painting Competition. She chose the rugged Yucca blossoms as her subject because she had never seen them painted before, perhaps remembering teacher John Carlson’s admonition to “make strong pictures, not necessarily pretty ones.”

With the $2,500 award money she received from the Texas competition, she joined the art teacher and lecturer George Elmer Browne’s group for an eight-month study abroad. Emmett Hull, who had planned to join his wife in the fall, changed his plans after the financial crash of 1929. While in Europe, Marie produced over six hundred oils and watercolors that reflected her travels. St. Cere is an example of her travel paintings. She expanded her European study by visiting prestigious galleries and museums, such as the Prado in Madrid and the Louvre in Paris.

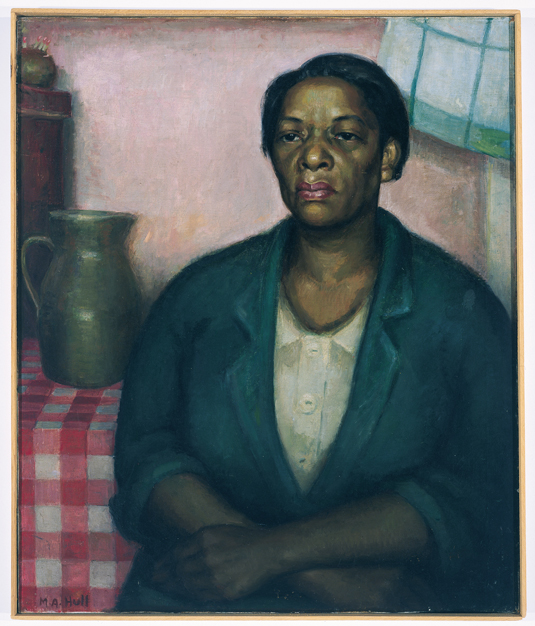

Back in America, she traveled to every exhibition she could afford. During the difficult economic times of the Great Depression, she often traveled by train all night to save the expense of a hotel. She painted portraits of white tenant farmers and black servants and workers, partly because they sat for little pay, but mainly because she saw such beauty in them. Sharecropper: The Egg Man is an example of her Great Depression paintings. She said, “I find that people who live close to the earthly, fundamental things usually have more character in their faces. They have an unmasked look.”

The artist as experimenter

Marie Hull experimented in many media: sculpture, lithography, etchings, silkscreens, and woodblock prints, along with her oil paintings, drawings, and watercolors. She became known for her rich, intense colors. She often joked that she liked any color as long as it was pink. She painted portraits of many prominent Mississippi figures, among them Governor Thomas L. Bailey and historian Dunbar Rowland.

Her reputation steadily grew. In 1931 her painting Church at Penne, France was selected for the Spring Salon in Paris, the only international juried exhibition open at that time. Two of her sharecropper paintings were selected for major exhibits in 1939 — one in the Golden Gate Exposition in San Francisco and one at the New York World’s Fair. Moreover, her works were shown in museums all over the country. She was also very much appreciated in her home state.

In spite of her growing number of awards, Marie Hull remained an unassuming person who was always ready for the next adventure. Once at an exhibit in St. Petersburg, Florida, a rug dealer fell in love with her work. “He bought practically everything I had,” Hull said, “and I landed back in Jackson with little money but about twenty Oriental rugs.”

Marie Hull’s desire was simply to make art, not to make a name for herself. She never settled for a particular style, but her work is generally divided into three periods: traditional (1912-1940); transitional (1940-1955); and contemporary. Hull never stopped experimenting.

She said, “Progress and change are the essence of living — for artist and non-artist. Without it, stagnation and deterioration soon become evident. People who expand their knowledge and investigate, remain more youthful, have joyous experiences, and become more mentally alert.”

Her early works show a firm command of drawing and deep understanding of anatomy. They are mostly “representative,” meaning she painted realistically in the traditional style. Her portrait, Melissa, is a fine example of this traditional style and also shows her sensitivity to a model’s earthy qualities.

In the 1940s, she encouraged one of her best young students, Andrew Bucci, to study at the Art Institute of Chicago, which she considered “the center of modern art teaching.” She learned everything she could from Bucci when he returned to Mississippi. Her modern paintings with diagonals, arabesques, and circles in bold pink, blue, black, and yellow, show her fascination with color relationships and design.

From the mid-1950s on, her works explode with color and texture. In a painting called Bright Fields, reality gives way to feelings stirred by bright pinks, oranges, and reds. These works are sometimes categorized as impressionism, abstract expressionism, and expressionism. Marie Hull referred to many of her modern paintings as lyrical abstractions. (Impressionism is a style in which the artist depicts the visual impression of the moment, especially in terms of the shifting effect of light and color — the paintings of Claude Monet and Pierre-Auguste Renoir are in this style; expressionism is a style of painting in which the artist expresses feelings rather than images of the external world — Vincent Van Gogh and Edvard Munch are expressionist painters; abstract expressionism, is art aimed at emotional expression with particular emphasis on the creative spontaneous act, for example, action painting. Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning are abstract expressionists.)

Although at times Marie Hull’s works show the influence of great artists such as Monet, her works defy easy categories. Most of the time, she drew inspiration from her own surroundings — she and her husband lived in Jackson at 825 Belhaven Street in the Spanish-style house he designed. She once stated that her ideas rose from “a street pavement’s cracks, the rhythms and patterns formed by rocks in a gravel walk, the beauty of red Mississippi clay.”

The artist as public figure

Marie Hull won many prizes, culminating with the Katherine Bellaman Prize presented to her at the Governor’s Mansion in 1965. In 1966, the Mississippi Art Association staged a retrospective of her work in Jackson. The first painting in the retrospective was a still life painted in 1916. She painted the last piece, Lilies, only a few minutes before the show. The canvas was still wet.

Mississippi Governor William Waller designated October 22, 1975, “Marie Hull Day.” The next month, the Mississippi Art Association and Delta State University staged a major retrospective exhibition of her work at the Fielding Wright Art Center at Delta State University in Cleveland, Mississippi, and at the Municipal Art Gallery in Jackson.

In 1977, Hull fractured her hip and was admitted to a nursing home — her husband had died October 20, 1957. After moving into the nursing home, art was an adventure that continued to call. Until a few weeks before her death on November 21, 1980, at age ninety, she was still painting.

Marion Barnwell is English professor emerita, Delta State University. She resides in Jackson, Mississippi.

Mississippi History Now appreciates the assistance of Ron Koehler, chairman of the art department at Delta State University in Cleveland, Mississippi, for photographing the Marie Hull paintings used in this article from the university’s Marie Hull Collection.

Mississippi History Now appreciates the assistance of Beth Batton, curator of the collection and public programs at the Mississippi Museum of Art in Jackson for providing digital copies of the Marie Hull paintings used in this article from the museum’s collection.

Note: in 2009, Belhaven College became Belhaven University.

Lesson Plan

-

Marie Hull (American, 1890-1980) Self-portrait, no date, pastel on paper. Collection of Mississippi Museum of Art, Jackson. Anonymous gift. -

Marie Hull (American, 1890-1980) Flamingoes, oil on canvas, circa 1925. This painting was done in Florida while Marie and Emmett Hull resided there. Rich intense colors are characteristic of a Hull painting. Courtesy Delta State University Art Department, Marie Hull Collection.

-

Marie Hull (American, 1890-1980), St. Cere, July 17, late 1920s, watercolor and graphite on paper. Collection of Mississippi Museum of Art, Jackson. Bequest of the artist. An architectural subject from Hull’s European study in 1929. -

Marie Hull (American, 1890-1980) Sharecropper: The Egg Man, oil, 1939. This painting is part of Hull's Depression series of sharecroppers. Courtesy Delta State University Art Department, Marie Hull Collection. "I find that people who live close to the earthly, fundamental things usually have more character in their faces. They have an unmasked look," Hull said. -

Marie Hull (American, 1890-1980), Melissa, 1930, oil on canvas. Collection of Mississippi Museum of Art, Jackson. Purchase. -

Marie Hull (American, 1890-1980), Lilies, 1930, oil on canvas. Collection of Mississippi Museum of Art, Jackson. Purchase.A classic example of what Hull meant when she said, "I have always put great stress on anatomy and learned the value of knowing the construction of whatever I was going to draw." -

Portrait of Governor Thomas Lowry Bailey by Marie Hull (American, 1890-1980). Oil on canvas. Courtesy Delta State University Art Department, Marie Hull Collection. -

Marie Hull at work during her "transitional" period -- from the traditional to abstract. Courtesy Mississippi Department of Archives and History, PI/COL/1981.0066, No. 47. -

Marie Hull (American, 1890-1980), Bright Fields, 1967. oil on canvas. Collection of Mississippi Museum of Art, Jackson. Purchase. -

Marie Hull and artist and educator Malcolm Norwood with her painting Annie Smith at a retrospective of her paintings at Delta State University in 1970. Courtesy Mississippi Department of Archives and History, PI/ART/H85.5, No. 1.

References:

Black, Patti Carr. Art in Mississippi: 1720-1980. Jackson, Mississippi: University Press of Mississippi, 1998.

Norwood, Malcolm, Virginia Elias, William Haynie. The Art of Marie Hull. Jackson, Mississippi: University Press of Mississippi, 1975.

Marie Hull 1890-1980: Her Inquiring Vision. Preface by Mary D. Garrard. Text by Malcolm Norwood and Jessie J. Poesch. Cleveland, Mississippi: Delta State Art Department, 1990.

Marie Hull and Her Contemporaries, Theora Hamblett and Kate Freeman Clark. Essay by Elise Brevard Smith. Catalogue and text by Liliclaire C. McKinnon. Mississippi Museum of Art, 1988.

Mississippi Department of Archives and History. Marie Hull Subject File.