The music called the blues that emerged from Mississippi has shaped the development of popular music in this country and around the world.

Turn on the radio. You might pick up some rock with some tough guitar riffs – or some rap. But put on Robert Johnson’s recording of “I Believe I’ll Dust My Broom,” and you’ll hear it all – set down in the 1930s by a man who combined elements of the music he heard with the genius that he got from God knows where – maybe the devil, if you want to believe the legend.

And what about rap? Skip James, born Nehemiah Curtis James about 1902 in rural Mississippi near Bentonia, talks about “rappin’ along” in the 1920s. About the same time “Big” Willie Dixon, in Vicksburg, was writing his first song, “Signifying Monkey,” a piece straight out of the age-old convention of “signifying” – better known now as “rapping.”

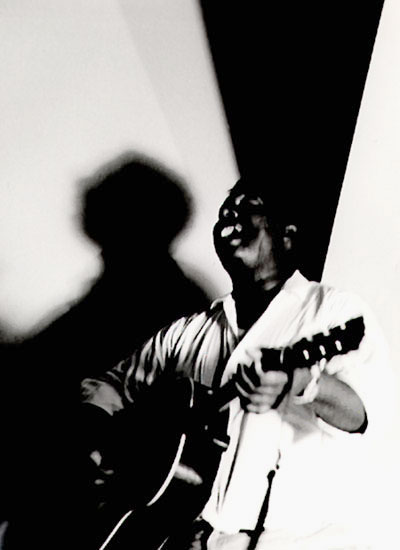

The blues and Mississippi are synonymous to music lovers. The repertoire of any blues or rock band is full of songs, guitar licks, and vocal inflections borrowed from Mississippi bluesmen – from Robert Johnson, Charley Patton, Tommy Johnson, and Son House to Skip James, Mississippi John Hurt, Mississippi Fred McDowell, Sonny Boy Williamson, Big Joe Williams, Bukka White, and Furry Lewis – just to mention some of the early ones. A couple of generations later, Willie Dixon, Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf, B.B. King, James Cotton, and many others were still making Mississippi blues and sending it out all over the world.

Birth of the blues

As far as historians can tell, the blues were born in the Mississippi Delta, an elaboration on work chants, “sorrow” slave songs, and the lyrical and haunting “field hollers.” As early as the American Civil War, White soldiers noted a different music created by Black soldiers – songs about marching and other toils of war in which they “extemporized a half-dissonant middle part.” These songs were direct precursors to the blues, if not the real thing already.

By the 1890s, the blues form had been set and the sounds of a distinctive new music began to be heard beyond the work camps. The new music was filled with the polyrhythms and tonalities of African music and bore the nuances of many different tribes. Black Americans had borrowed substantially from White man’s music too – its scale, its rich folk traditions, its instruments. The blues did not emerge from Africa; it was born out of two musical cultures – Black and White – that were thriving and growing separately and together. The result of this large-scale mixing was music that was to be the basis of mainstream popular music for the entire 20th century.

Juke joints

With the growth of the blues came the spread of a phenomenon known as the “juke joint.” In these makeshift buildings that served as social clubs, the blues developed and spread. Songs and lyrics were borrowed, adapted from musicians who traveled from joint to joint, and techniques and styles were copied and elaborated upon. Young bluesmen found mentors and left home to follow them in a life on the road.

The first Mississippian to emerge from the anonymous folk tradition was Charlie Patton. Born near Edwards about 1887, he moved to Dockery Plantation in the Mississippi Delta to work. He began playing around the Delta at juke joints, dances, fish fries, and house parties. During those years, 1897 to 1934, he traveled with another blues great, Son House, tutored the young Howlin’ Wolf, and inspired countless others.

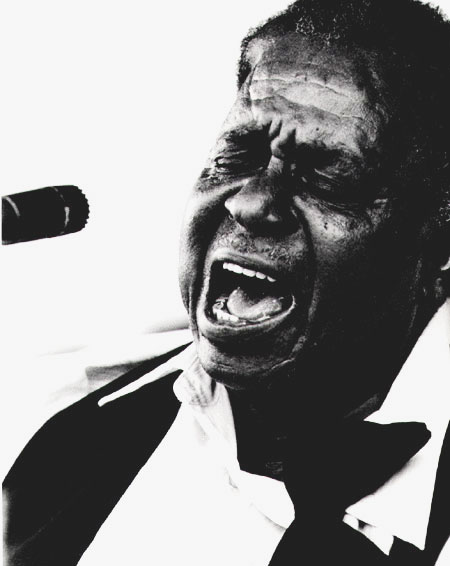

Eddie “Son” House was born in Coahoma County in 1902. Often regarded as the quintessential blues singer, he did not begin performing until his mid-twenties, because he was first a preacher. Preaching was a powerful influence on his forceful singing style. In 1930 he recorded two songs for the Paramount label: “Preachin’ the Blues” and “Dry Spell Blues,” about a farming crisis in the Delta. Son House is famous for his bottleneck slide technique. This technique is characteristic of blues music – the musician uses the guitar as a second voice by sliding a bottleneck or other hard object along the strings to make a wailing sound. After he was rediscovered in the 1960s, House played for a decade to college audiences and at blues festivals.

Robert L. Johnson

The most potent legend in the blues was Robert L. Johnson. He was born near Hazlehurst and ran away from home as a teenager to learn guitar from Son House. Legend has it that Johnson sold his soul to the devil in exchange for his talent to play and sing the blues better than anyone else. He worked the Delta, then traveled the upper South and East. His recording sessions in 1936 and 1937 produced some of the richest music in the history of the blues: “Crossroads,” “Love in Vain,” “Hellhound on my Trail,” and “Dust My Broom,” among others. His guitar and vocal skills established a foundation on which generations of blues and rock musicians have been building ever since.

Tommy Johnson, like Robert Johnson (no relation), claimed he too had sold his soul to the devil in exchange for his amazing guitar skills. The story is an old one, with roots in voodoo and African lore, but one that is effective only when the storyteller’s skills are as extraordinary as those of Tommy Johnson or Robert Johnson. Tommy Johnson, known for his song “Canned Heat,” a name taken by the 1960s blues band, was an early guitar stuntman. His contemporary, Houston Stackhouse, reported, “He’d kick the guitar, flip it, turn it back of his head and be playin’ it. Then he’d get straddled over it like he was ridin’ a mule – pick it that way.”

When African American musicians emigrated northward to cities like Chicago, they heard the music of tin pan alley and jazz. They began to amplify their instruments electrically and to add drums and even horns. The single bluesman was transformed into the blues band, and a new era had begun.

North to Chicago

One of the first Mississippians to take the blues to Chicago was Big Bill Broonzy of Scott. He arrived there in 1920 and played “for chicken and chitlin at Saturday night rent parties.” By the late 1930s, he was one of the most popular performers in the country and became a mentor to many Mississippi blues musicians who followed him north.

But Broonzy’s smooth “city blues” style was soon superseded; the urgency of the “new” blues, brought by Sonny Boy Williamson and Walter Horton, captured Chicago audiences.

The king of the Chicago blues was Muddy Waters. Born in Rolling Fork in 1915, Waters (McKinley Morganfield) set a new style for the blues. Recorded first by the Library of Congress in 1941 at Stovall Plantation (listen to the Muddy Waters recording), Muddy Waters by 1947 was making a name on Aristocrat (later Chess) Records. His “Hoochie Coochie Man” sold over 75,000 copies. “Rollin’ Stone” sold 80,000 copies and inspired Bob Dylan’s later song and the name of the 1960s rock band.

Howlin’ Wolf (Chester Burnett), born near West Point in 1910, started recording in Memphis with Sam Phillips. At home he had heard Mississippi country yodeler Jimmie Rodgers’s records and tried to imitate him. “I couldn’t do no yodelin’,” he said, “so I turned to growlin’, then howlin’, and it’s done me fine.” Wolf was picked up by Chess Records, which produced hits like “Spoonful” and “Evil Goin’ On.”

The source of most of the songs sung by Chess recording stars like Howlin’ Wolf and Muddy Waters was “Big” Willie Dixon, born in Vicksburg in 1915. A talented bass player, record producer, and scout, in addition to songwriter, Willie Dixon is known as the granddaddy of the Chicago blues.

Harmonica player Charlie Musselwhite was the only White Chicago bluesman during the era to play Southside clubs with Black bands. Growing up in Kosciusko, Musselwhite heard his father playing country music, but he gravitated to music of bluesmen because “their music told the truth.”

Many other Mississippi blues greats relocated to Chicago: James Cotton, Otis Rush, Otis Spann, Sunnyland Slim, Jimmy Dawkins, Albert King, Big Joe Williams, Magic Sam, and Elmore James.

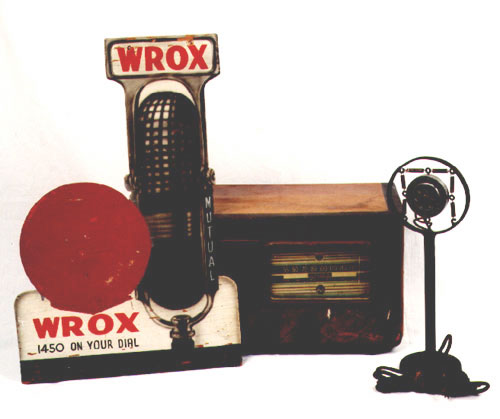

Through the blues, Mississippians communicated support, hope, even joy – in field hollers, across crowded juke joints and rural barn dances, and across the wires to fans tuning in their favorite radio shows. Mississippi musicians looked to music for much of the joy in their lives. Maybe that is the real legacy of their music.

Christine Wilson is director of publications for the Mississippi Department of Archives and History and managing editor of The Journal of Mississippi History, the quarterly publication of the Mississippi Historical Society.

Further Reading

- Cook, Bruce. Listen to the Blues. New York: Scribner’s Sons, 1973.

- Evans, David. Big Road Blues: Tradition and Creativity in Folk Blues. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1982.

- Grossman, Stefan. Delta Blues Guitar. New York: Oak Publications, 1969.

- Palmer, Robert. Deep Blues: A Musical and Cultural History of the Mississippi Delta. New York: Penguin Books, 1982.