A Gloomy Day in Newport

“It’s a gloomy day at Newport, It’s a gloomy, gloomy day.

It’s a gloomy day at Newport, My music’s going away.

What’s gonna happen to my music? What’s gonna happen to my song?”

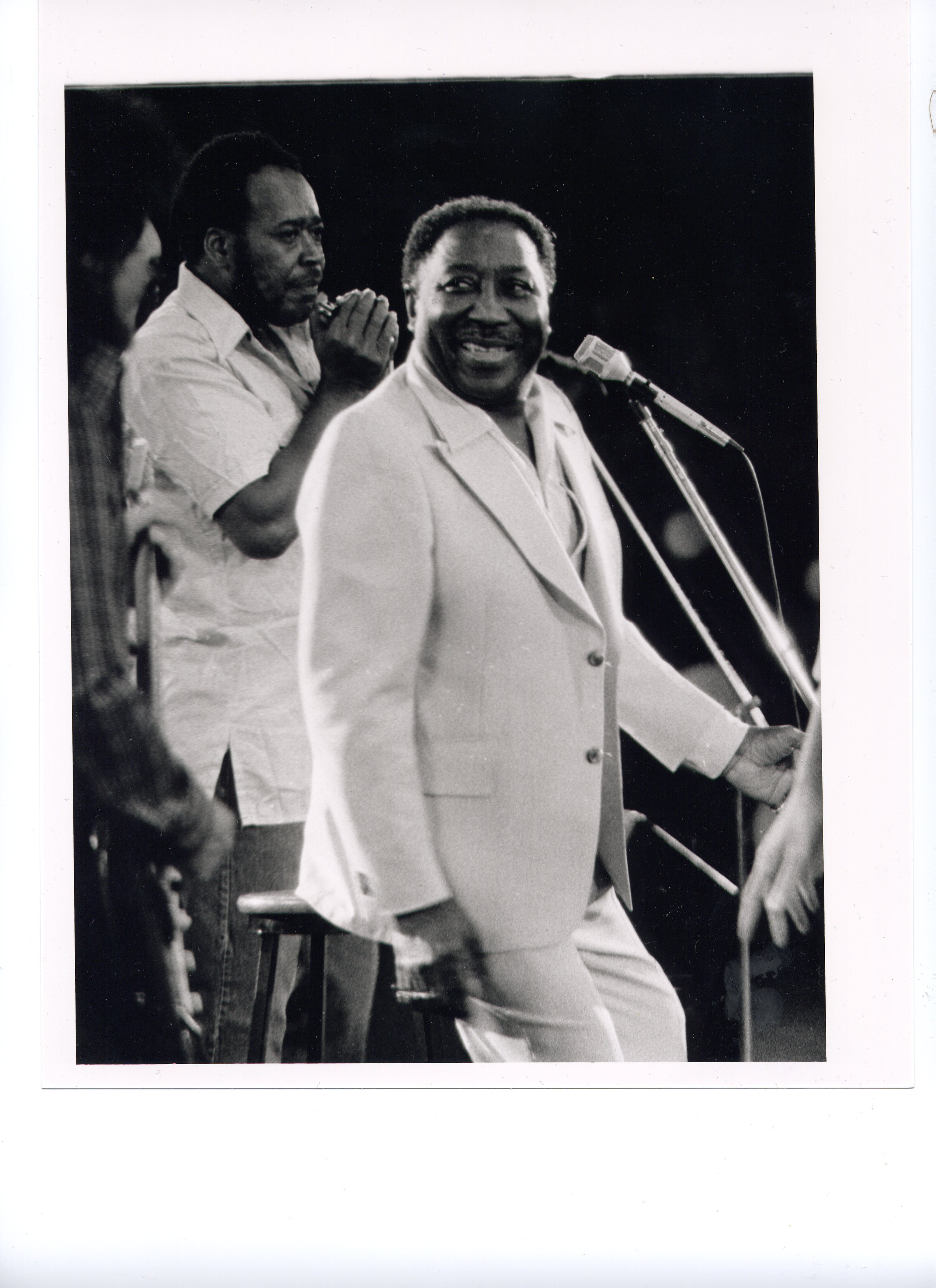

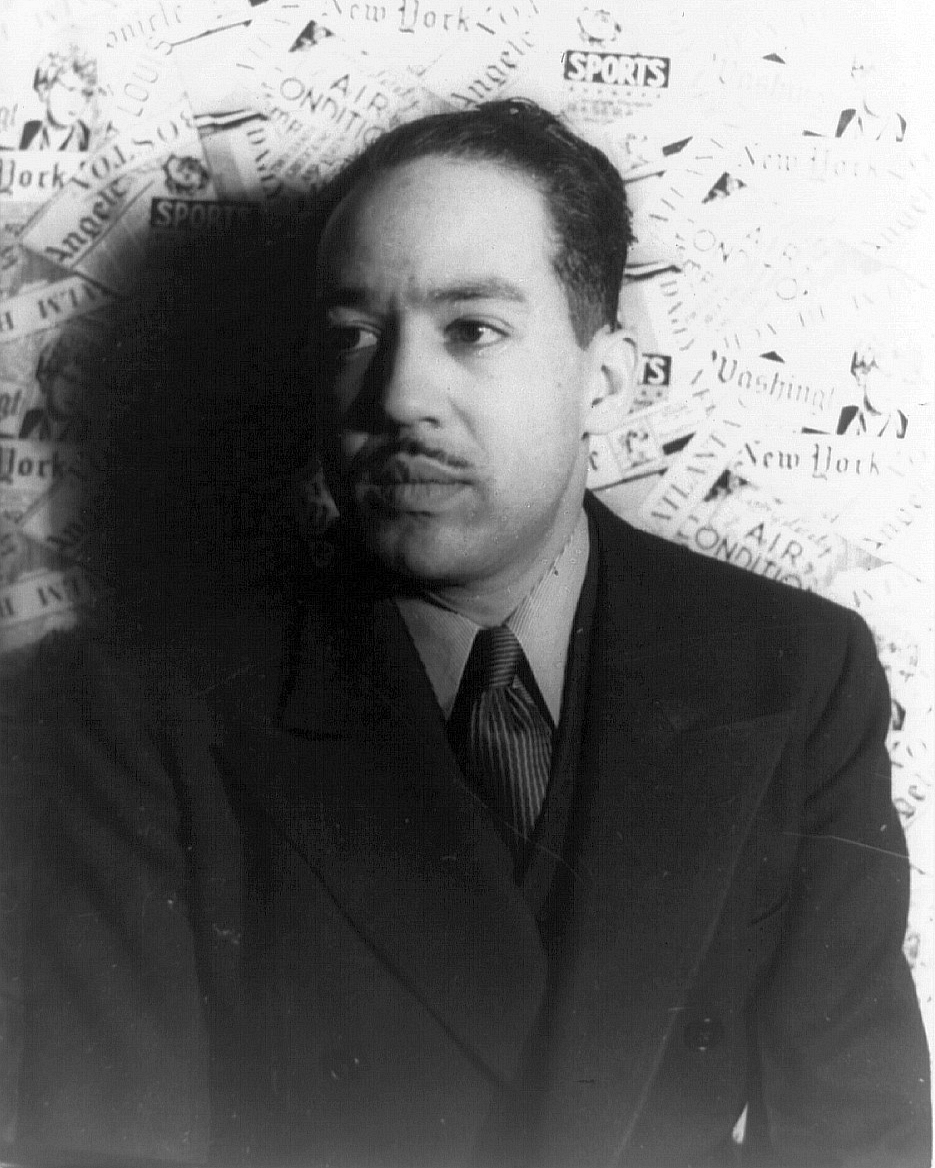

Otis Spann, pianist for the Muddy Waters Band, sang the lines of the song that poet and Newport Jazz Festival board member Langston Hughes had written earlier that day. It was the final song of the blues music session scheduled for Sunday afternoon, July 3, 1960. Langston Hughes wrote the song on the back of a Western Union blank after he learned that the Jazz Festival was cut short due to a riot the night before. Saturday evening thousands of people rioted because they could not get into the performance at Freebody Park. The National Guard and state police were called in to quell the riot. Because of the riot, Muddy Waters's blues session was the final act of the Jazz Festival. Hughes had planned the blues session on Sunday to introduce the blues to the White Jazz fans at the festival. The blues session is considered the first time that blues was played for a large White audience in America. According to David Whiteis, Muddy Waters’s performance at Newport “ranks as one of the most culturally and musically significant moments of the 20th century.”

The Sunday blues performance included the Sammy Price Trio, Betty Jeanette, Al and Leone, John Lee Hooker, Butch Cage and Willie Thomas, Myra Johnson, and the Muddy Waters Band. Interspersed into the musical performance was an educational presentation to initiate the audience into the blues. This educational presentation included Langston Hughes's “Narrating the Blues.” During “Narrating the Blues” Hughes used a call-and-response format asking questions that another performer would answer. In this way, Hughes defined and described blues music to the audience. For example,

Langston Hughes: “Sammy, what are the blues?”

Answer: “The blues ain’t nothin’ but the dog-gone hear disease.”

Langston Hughes: “Lafayette, what’s the blues?”

Answer: “The blues ain’t nothing but a good man feelin’ bad.”

Langston Hughes: “Drummer man, what is the blues?”

Answer: “The blues ain’t nothin’ but wantin’ what you never had.”

Langston Hughes: “Betty Jeanette, tellin’ me, what are the blues?”

Answer: “Blues ain’t nothing but a good woman been done wrong.”

Through the call and response, Hughes demonstrated the sense of melancholy that “captured the suffering, anguish-and-hopes-of 300 years of slavery and tenant farming” that characterized Blues lyrics. If “Narrating the Blues” provided the audience with an introduction to the lyrical themes of the blues, the Sunday performance by the various blues musicians accomplished Hughes’s goal to promote “African American culture through music” which was one of the reasons he became involved with Rhode Island’s Newport Jazz Festival in 1956.

The Muddy Waters Band was the final act of the Sunday Blues performance. Chess Records released the performance as a live album, Muddy Waters at Newport 1960, and included many of his hits from the 1950s including “Hoochie Coochie Man” (1954) and “Got My Mojo Working” (1957). The final song of the album is “Goodbye Newport Blues” which was written by Hughes and performed by the Muddy Waters Band. The Newport Jazz Festival not only introduced the Blues to White America but according to Gary Blailock, Muddy “Waters and his band unleash(ed) the full force of the blues on a transfixed audience.” Blailock’s assessment can be confirmed by listening to the full album or watching videos of the performance that are readily available on the internet. For example, during the Muddy Waters Band’s performance of “Got My Mojo Working,” the camera often shifted from the Muddy Waters Band performing on stage and the primarily White audience enthusiastically dancing, clapping hands, rocking in their seats, smiling, and taking pictures. At the end of the song, many in the audience gave the band a standing ovation and the enthusiasm seemed to encourage the band to begin playing the song again to a visibly pleased audience. The same effect on the audience is evident in the album Muddy Waters at Newport 1960 when Muddy Waters asked the audience, “Do you want me to sing a little more or something else?” after singing “Got My Mojo Working,” the audience almost in unison responded with an immediate “yes,” which led to a second round of the song. Hughes’s goal was to introduce the blues and Waters to a larger audience and after Newport, Muddy Waters’s audience expanded to include White fans of jazz music. Further, his performance resulted in many young Whites in America “embracing the blues.”

Taking the Delta Blues to Chicago and Beyond

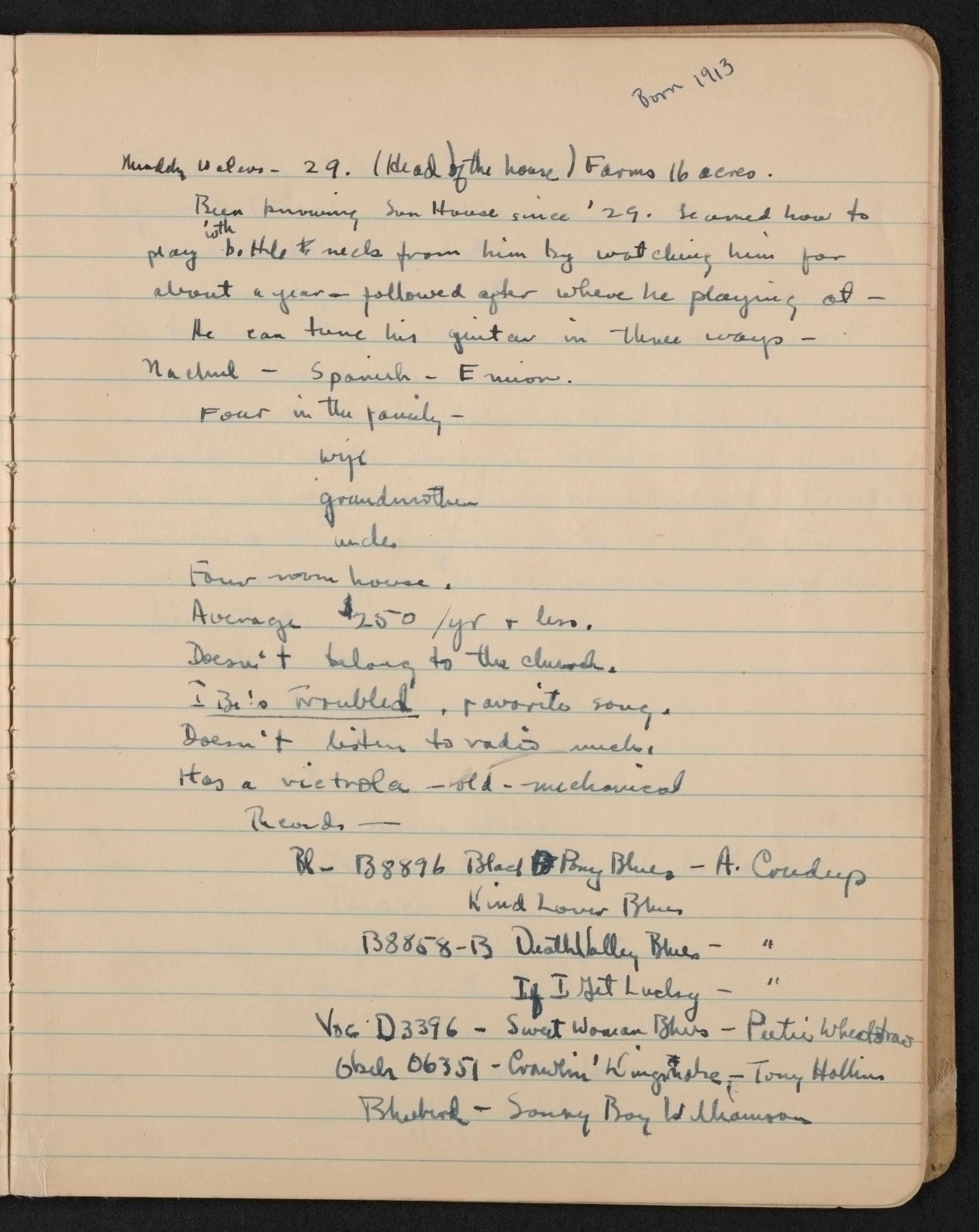

Muddy Waters (born McKinley Morganfield) was born at Jug’s Corner in Issaquena County, Mississippi in 1913. The date of his birth has been reported variously as 1913, 1914, and 1915. Alan Lomax recorded the year of his birth as 1913 in his 1941 interview with Waters. Lomax was traveling the Deep South for the Library of Congress recording folk music in 1941 and 1942. A page from Lomax’s journals, which are available at the Library of Congress, is included below. In his notes, Lomax wrote that Waters shared that he learned how to play guitar from legendary blues artist Son House, could tune a guitar three different ways, and reported his yearly income working as a sharecropper was less than $250.

Alan Lomax recorded Muddy Waters performing the blues in August 1941 and July 1942. These recordings are available on The Complete Plantation Recordings Muddy Waters. Musically, the songs on the recordings are different from the songs he would later record in Chicago in that Waters is playing an acoustic guitar. In Chicago, he transitioned to an electric guitar. Still, the theme of disappointment and loss is evident in his lyrics. For example, after Waters played the song “Country Blues,” Lomax asked him why he wrote the song. Muddy Waters replied that he “had been mistreated by a girl . . .” and “I just felt blue, and the song fell into my mind.” After the second interview with Lomax, Waters determined that he could be a professional musician. He subsequently followed other Black Mississippians' example and migrated north to Chicago in 1943.

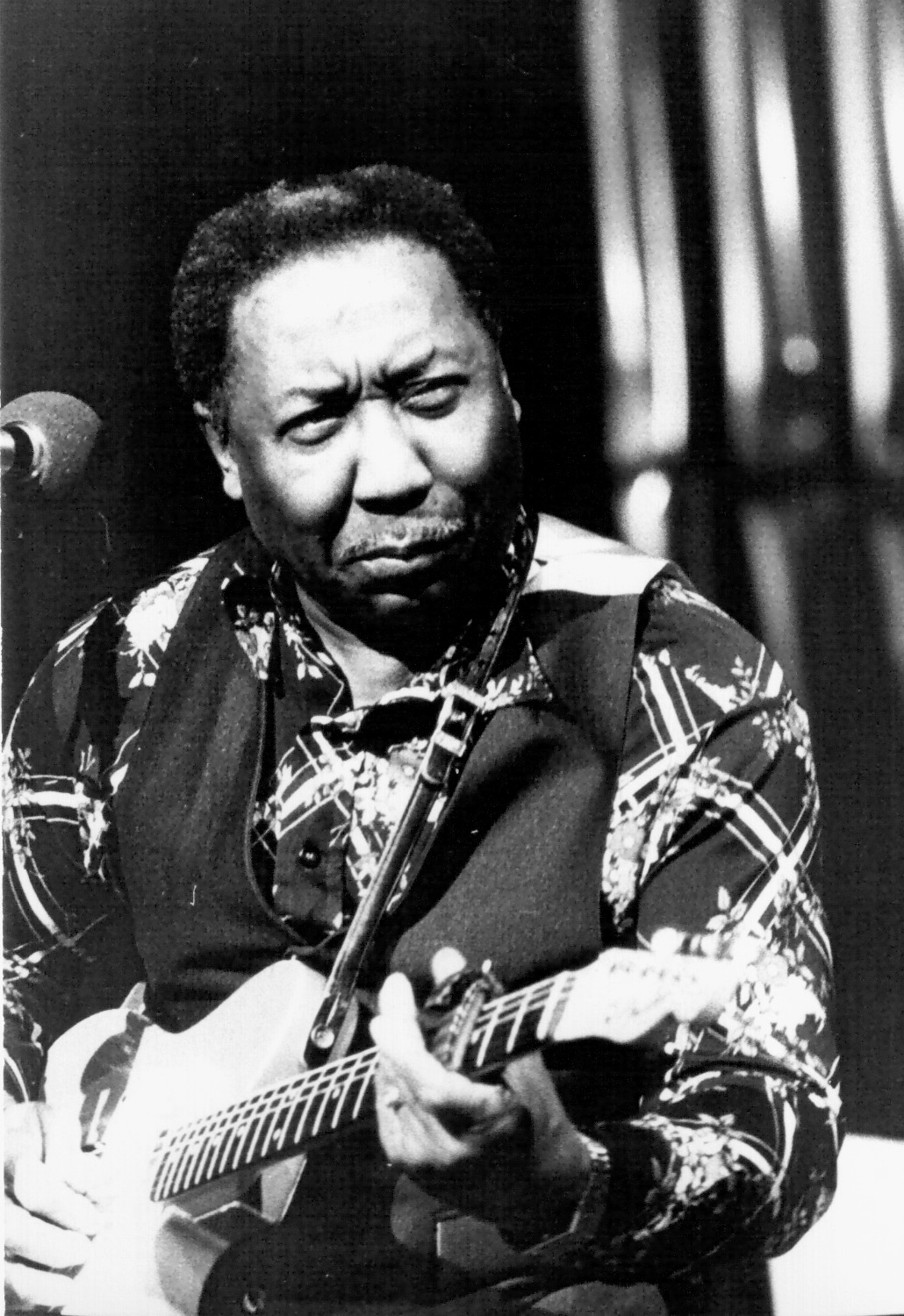

In Chicago, Muddy Waters modified his Delta Blues sound when he exchanged his acoustic guitar for an electric guitar. In some accounts, he bought an electric guitar in 1944; others state that his uncle gave him the electric guitar. According to Michael Hill, he made the switch because he “found he couldn’t command much attention unamplified in a crowded, noisy club.” It was this new electric sound that brought Muddy Waters commercial success leading to 16 hits on the R&B charts by 1960. And it was this sound that he brought to the largely White audience at Newport in July 1960.

As the “king of the Chicago blues,” he played primarily for Black audiences in Chicago but in the late 1950s he began branching out to a larger audience. In 1958, Muddy Waters toured England playing with the Chris Barber Band. According to one writer, it was Waters’s tour of England that contributed to the intense British interest in blues claiming that after the tour, “countless 10-15-year-olds were listening in the bedrooms to hard-to-come-by blues records they might have owned or borrowed.”

The Blues Had a Baby and They Called it Rock and Roll

Muddy Waters’s electric Delta Blues was a watershed in modern music in many ways. First, he influenced generations of guitar players. According to Michael Hill, Muddy Waters “electrified the blues” and his guitar “launched a thousand bands.” Further, Rolling Stone magazine reported that some of the most accomplished rock guitarists acknowledged Waters’s influence, including Jimi Hendrix, Eric Clapton, Jimmy Page, and Angus Young. Many guitarists who have imitated his riffs compare Waters’s guitar riffs in “Mannish Boy” to George Thorogood in “Bad to the Bone.” Second, his blues groups included the elements that would become the modern rock band including two guitars, bass guitar, drums, and a piano. Third, many rock and roll musicians were influenced by him. In his song, “The Blues had a baby and they named it rock and roll,” Waters sang

“All you people, you know the blues got a soul

Well this is a story, a story never been told

Well you know the blues got pregnant

And they named the baby Rock and Roll.”

In the song, written in 1977, Muddy Waters acknowledged his and other blues musicians’ role in shaping rock and roll. Among the significant artists who were shaped by Waters are the Rolling Stones and Eric Clapton. The Rolling Stones took their band name from a Muddy Waters song, and Eric Clapton in an interview with National Public Radio acknowledged that he was most influenced by Muddy Waters. He stated that he would listen to Waters and try to “emulate the guitar great’s technique.” Clapton and Waters played and toured together. In fact, Waters’s final live performance was with Clapton in Miami on June 30, 1982. Clapton, Rolling Stones’ lead singer Mick Jagger, and Stones’ guitarist Keith Richards were among the young people listening to blues music in England after Waters’s 1958 tour.

Long Lasting, Living Legacy

Muddy Waters’s accomplishments and influence as a musician have been recognized by many. Most notably, he was inducted into the Blues Hall of Fame (1980) and the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame (1987). He was nominated by the Recording Academy of the United States for twelve Grammy Awards and won seven. The seventh was a Lifetime Achievement Award in 1992 which is given to those “who, during their lifetimes, have made creative contributions of outstanding artistic significance to the field of recording.” Interestingly, two of the groups that claim significant influence from Muddy Waters also have been recognized with the Lifetime Achievement Award by the Recording Academy—the Rolling Stones in 1986 and Cream (Eric Clapton played guitar for Cream) in 2006.

Langston Hughes intended for the blues performance including Muddy Waters Band at Newport to broaden the appeal of blues music to a White audience. The performance at Newport did just that. More significantly, Waters’s Newport performance serves as a microcosm of his larger influence on popular culture and music. At Newport, Waters brought his Chicago blues sound that had previously been performed primarily in front of Black audiences to a largely White audience. His larger influence brought the Delta blues from Mississippi to the world through the musical artists he helped shape in rock and roll, jazz, R&B, country and western, and hip hop. On that gloomy day in Newport in July 1960, Langston Hughes and the Muddy Waters Band asked what was going to happen to the blues. The answer is one they might not have anticipated. The blues would transform popular music and Muddy Waters’s music would be an influential part of that transformation.

Post-Script: The Spread Continues Today

Waters and Hughes’s legacy of spreading the blues continues. In October 2023, the Rolling Stones released, Hackney’s Diamonds, their first studio album since 2005. One of the songs is a cover of Muddy Waters’s song “Rolling Stones Blues.” Joe Taysom described the Rolling Stones as a “gateway band” that encourages people to seek out the blues. With their cover of Muddy Waters’s “Rolling Stones Blues,” the band continues to honor his legacy and influence on their music. They continue to help spread the blues as their music provides an avenue for listeners to become fans of Muddy Waters and the blues.

Dr. Kenneth Anthony is an Associate Professor and Undergraduate Program Coordinator in the Elementary Education Program in the Department of Teacher Education and Leadership at Mississippi State University. He is the Co-principal investigator of the Teaching with Primary Sources Mississippi grant (Library of Congress Teaching with Primary Sources).

Valencia Epps is a master’s student in Elementary Education at Mississippi State University. She is currently a graduate assistant in the Department of Teacher, Education, and Leadership.

Lesson Plan

-

Muddy Waters singing with other musicians at the Newport Jazz Festival. Credit: The Estate of Victor Kalin. -

Muddy Waters performing. By Jean-Luc Ourlin from Toronto ontario, Canada - Muddy Waters (with James Cotton), CC BY-SA 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=47455750

-

Alan Lomax's notes on Muddy Waters's interview. Credit: Alan Lomax collection (AFC 2004/004), American Folklife Center, Library of Congress -

Otis Span playing piano. Credit: The Estate of Victor Kalin. -

Muddy Waters performing. By Lionel Decoster - Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=74824993 -

Langston Hughes, poet and playwright. By Jack Delano, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Sources

Langston Hughes, “Newport Blues,” July 3, 1960, Langston Hughes Papers. James Weldon Johnson Collection in the Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. https://collections.library.yale.edu/catalog/17394775.

Victor Kalin, “Otis Spann Singing Langston Hughes’ newly composed Newport Blues,” July 3, 1960, Langston Hughes Papers. Credit Victor Kalin Estate. https://archives.yale.edu/repositories/11/archival_objects/347615.

Jack Tracy, Original liner notes from the album Muddy Waters at Newport 1960, (Waxtime Records, 2013).

Rick Massimo, I Got Song: A History of the Newport Folk Festival. Middletown, Connecticut, Wesleyan University Press, 2017, p. 27.

David Whiteis, “Blues Breakthrough at Newport,” n.d., The Coda Collection. https://codacollection.co/stories/blues-breakthrough-at-newport.

“Newport Jazz Festival: Program, 1960 July 3.” July 3, 1960. Langston Hughes Papers. https://archives.yale.edu/repositories/11/archival_objects/348561.

Lucy Chauduri, “What is blues music?” Classical Music, BBC Music Magazine, November 28, 2022. https://www.classical-music.com/features/articles/blues-music/

“What is the Blues?” The Blues. PBS. https://www.pbs.org/theblues/classroom/essaysblues.html.

Khagendra Neupane, “The Intersection of Blues and Gospel in Langston Hughes’s Poetry”. Cognition, 5 (1):63-67, 2023. https://doi.org/10.3126/cognition.v5i1.55409.

Gary Blailock, Liner notes, Muddy Waters at Newport, 1960, (Waxtime Records, September 2013).

“Muddy Waters Newport Jazz Festival 1960,” https://youtu.be/fLTCIqfsefc?si=Xw22XEY7chdyXEQ0.

Muddy Waters at Newport, 1960, Side Two, (Waxtime Records, September 2013).

Michael Hill, “Muddy Waters Hall of Fame Essay,” Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, 1987 https://www.rockhall.com/inductees/muddy-waters.

Karl Rohr, “Muddy Waters,” Mississippi Encyclopedia, Center for Study of Southern Culture, July 11, 2017, http://mississippiencyclopedia.org/entries/muddy-waters/.

Born McKinley Morganfield as cited by Karl Rohr, “Muddy Waters.”

According to the Mississippi Blues Trail marker at his birthplace, Muddy Waters claimed to have been born in Rolling Fork and his birth year has been variously reported as 1913, 1914, and 1915. https://msbluestrail.org/blues-trail-markers/muddy-waters-birthplace

Lomax, Alan. Alan Lomax Collection, Manuscripts, Mississippi, Tennessee and Arkansas, -1942. to 1942, 1941. Manuscript/Mixed Material. https://www.loc.gov/item/afc2004004.ms070352/.

Lomax, Alan. 1941. https://www.loc.gov/item/afc2004004.ms070208/.

The Complete Plantation Recordings Muddy Waters, 1941- 1942, Chess/ MCA, 1993.

“Country Blues” and “Interview #1” from The Complete Plantation Recordings Muddy Waters, 1941- 1942, Chess/ MCA, 1993.

Robert Gordon, “Can’t Be Satisfied.” American Masters. PBS, May 24, 2006. https://www.pbs.org/wnet/americanmasters/muddy-waters-cant-be-satisfied/730/.

Christine Wilson, “Mississippi Blues,” Mississippi History Now, Mississippi Department of Archives and History, August 2003. https://www.mshistorynow.mdah.ms.gov/issue/mississippi-blues.

“Did Muddy Waters’ First UK Tour Launch The British Blues Boom?” October 16, 2023, https://www.udiscovermusic.com/stories/muddy-waters-first-uk-tour/

Victor Kalin, “Leon James, Al Minns, Betty Jeanette, Otis Span, Muddy Waters, Jimmy Rushing, Cage Thomas, Sammy Price at piano, Newport Jazz Festival, July 1960,” July 3, 1960, Langston Hughes Papers. Credit Victor Kalin Estate. https://archives.yale.edu/repositories/11/archival_objects/347615.

Britto, David. “Artists that were influence by Muddy Waters: The American blues legend has left his mark on music and movies,” Rolling Stone India, April 4, 2023. https://rollingstoneindia.com/artists-influenced-by-muddy-waters-jimi-hendrix-rolling-stones-eric-clapton-martin-scorsese/.

“The Blues had a Baby and They Named it Rock ‘N” Roll,” Lyrics.com. https://www.lyrics.com/lyric/1072858/Muddy+Waters/The+Blues+Had+a+Baby+and+They+Named+It+Rock+%26+Roll

Melissa Block, “Eric Clapton Looks Back at His Blues Roots,” Interview heard on All Things Considered, NPR, October 17, 2007. https://www.npr.org/2007/10/17/15333469/eric-clapton-looks-back-at-his-blues-roots

Robert Palmer, “Muddy Waters: 1915- 1983: An obituary of the blues legend, with memories from Eric Clapton, Bonnie Raitt, Keith Richards and more,” Rolling Stone, June 23, 1983.

Recording Academy Grammy Awards. Lifetime Achievement Awards. https://www.grammy.com/awards/lifetime-achievement-awards

Naman Ramachandran, “Mick Jagger on New Rolling Stones Album, U.S. Politics and Mortality: ‘As You Get Older, a Lot of Your Friends Die,’” Variety, October 20, 2023. https://variety.com/2023/music/global/mick-jagger-rolling-stones-hackney-diamonds-1235762963/.

Joe Taysom, “How Muddy Waters Inspired The Rolling Stones,” Far Out Magazine, April 30, 2021. https://faroutmagazine.co.uk/muddy-waters-inspired-the-rolling-stones/