Personal recollections are valuable primary source tools for understanding historical events. They can be in the form of oral histories or written remembrances. The following is the text of a speech given by former secretary of state Dick Molpus at the Mississippi Department of Archives and History’s “History Is Lunch” program on June 18, 2014. The speech was made in commemoration of the fiftieth anniversary of the murder of three civil rights workers in Neshoba County, Mississippi, and presented in the House of Representatives Chamber of the Old Capitol Museum, Jackson, Mississippi. Molpus offers a unique perspective from his own personal experiences as a fourteen-year-old boy during the summer of 1964 in Philadelphia and discusses the importance of individual and communal action in the struggle for racial justice and reconciliation within the state of Mississippi. – Editor’s note

Today I am going to talk about people who step up to meet a problem and those who step back or who don’t step anywhere, in denial or to avoid an issue, and what that can eventually mean. But I have to set the stage: I grew up in Philadelphia, Mississippi, a saw mill town. There were three lumber companies, and my father owned one of them. There were also the glove factory and several construction companies. If you didn’t work in those places, you didn’t work. Although I think the environment I grew up in was very civilized, Neshoba County was really kind of a rough-and-tumble place.

Rather than sitting at home on Sunday nights watching the Ed Sullivan show, we would go to the “drunk tank” at the town jail to make sure that my father’s saw mill crew was out in time to come to work on Monday morning. That is how I spent a lot of Sunday evenings. Still, Philadelphia was a little Mayberry-type town. We walked everywhere. As I say, for those of us who were in the White middle class, it was kind of an idyllic place to grow up. Then around 1964 things started changing pretty rapidly. It was the time of Jim Crow. Fortunately, I had parents who taught me to call people “Mr.” and “Mrs.” and to recognize that we were all from the same human family. I was fourteen then, when things began to get worse.

Philadelphia sits on top of a hill—Beacon Street Hill. I remember we were driving up that hill one evening, and as we were coming up from the courthouse at about 11 o’clock, we saw crosses light up all across the courtyard square. I saw about six Klansmen jump in the back of a green pickup truck and drive away; we went over and woke up the night marshal, who was sound asleep. That was the first time that I had seen anything like that happen.

We started to hear about churches being burned and people being beaten. One night I was walking to what we called the “show”; we were walking past the jail when a police car drove up. One of the deputies pulled an older, African American guy out. He was reeling, obviously intoxicated. He said something to the deputy, and the deputy hit him right between the eyes. I heard his skull pop. I saw that, as a fourteen-year-old. We heard about other people being beaten. Mount Zion Church, a small church out east of town between Philadelphia and DeKalb, was burned because it was being used for voter registration activities.

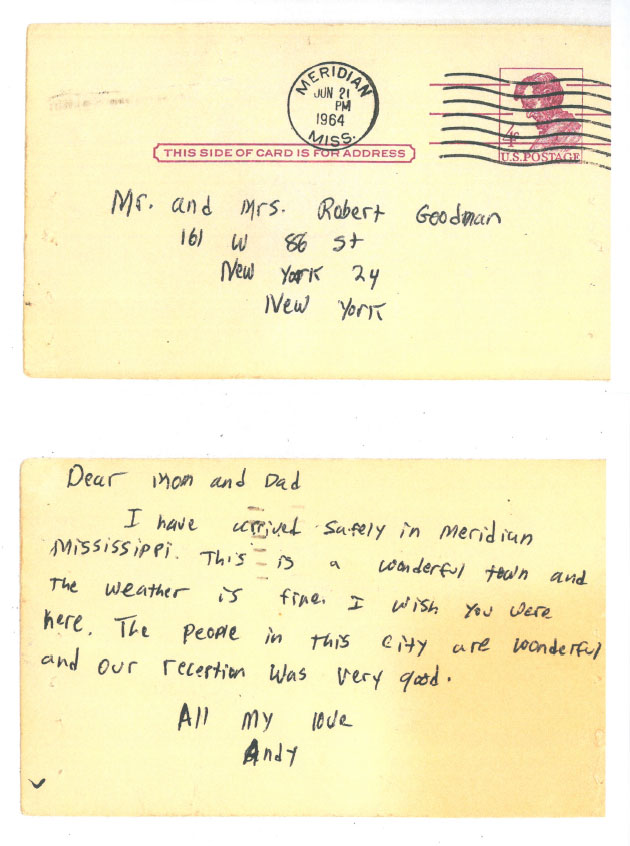

Then the young Freedom Summer volunteers James Chaney, Michael Schwerner, and Andrew Goodman drove in from Meridian to check on the Mt. Zion scene and were pulled over by Neshoba County Deputy Sheriff Cecil Price near the First Methodist Church. He took the young men to jail and held them for a number of hours (until the Klan got organized). The three students left, but got pulled over again and were taken to a place called Rock Cut, over on Rock Cut Road. I don’t have to relate the rest of that story. I took David Goodman to that site on Saturday, June 14, 2014. It was almost fifty years to the day when his brother was murdered. He had never seen the place where his brother was pulled out of the car and shot. It was a very poignant moment. He gathered about twenty rocks from Rock Cut Road, and we put them in a bag so that he could take them back and distribute them to friends and family.

Now, this small town was filled with good people—good people who were afraid to step up. Remember how the stories went about what had happened to James Chaney, Michael “Mickey” Schwerner, and Andrew Goodman? They had “gone up north, hiding, just to make Philadelphia, Mississippi, look bad.” But many—even we kids— knew that wasn’t true. We knew they were dead. We had even heard who was involved; we knew the names. But the community would not speak up. And when I say the community, I am talking about the White middle class, the business class. I am not talking about African American churches, where there were a lot of courageous leaders. But the community felt that Philadelphia was being attacked, which was a bizarre reaction. All of a sudden, Walter Cronkite was in Philadelphia, Mississippi. NBC, ABC, and other worldwide news crews were there, and the townsfolk felt they were being depicted as rednecks and that we should band together against these outsiders.

People do ask me about the churches, their positions on the violence. I went to the largest church in Philadelphia, and the last sermon that I heard in that church (because I didn’t go back) was after the young men were found. The preacher said that “those guys came looking for trouble, they got it, and if more come down, that is what will happen to them.” That was the spiritual leadership there. Although there was this one young Methodist minister named Clay Lee who obviously didn’t get the memo about how he should be acting. He spoke from the pulpit in a sermon called “The Spirit of Herod.” He gave the sermon and the same afternoon was in front of the church leaders; in short order, he was looking for another church appointment. He later became bishop of the United Methodist Church in Mississippi. The most spiritual leadership came from the African American community; virtually none came from the White Protestant churches—although the Episcopal Church and its twelve members did hang in there. A handful of White people in the community said, “You know what? We have murderers in our midst. We have people who would castrate someone. We have people who would break skulls, and we see their making us look like a bunch of rednecks as the main issue?”

Turner Catledge, executive editor of the New York Times then, had been editor of the Neshoba Democrat as a young man. He sent a reporter down, and one person in town told him, “Well, we are not really paying too much attention to what happened this summer because we are all real busy.” When the townspeople read that, they called a meeting and demanded that Turner Catledge come to Philadelphia to explain himself. They met at my father’s house—about thirty of the business and professional community—because we were related to Catledge. My job as a fourteen-year-old—my distinct honor—was to sit on the floor by him and, every time he shook his glass, to run into the kitchen and put more ice and scotch in it for him. I think he needed a fair amount of scotch that night. Finally, after the group had gone after his paper for a while, Catledge said, “Guys,” (it was all guys except for a few women in the back) “you’ll never have anything more important happen in your life or in the life of this community than what is happening right at this moment. You guys, rather than stepping up and taking charge, have let the worst element take over this town. They are your law enforcement. You’ve let the Ku Klux Klan run rampant and the Citizens’ Council, and you are missing your moral opportunity of a lifetime.” I was listening to this, and one of them finally said, “Well, Turner, you are from here, but you are not one of us anymore.” It was the same person who had been quoted in the paper as saying we were too busy to pay attention. And Turner Catledge shot back, “Well, let me ask you this: are you the one who told my reporter how ‘busy’ you had all been?” The fellow said, “That’s what I told him.” And Catledge said, “Well, you’re a damned fool.” That kind of put a damper on the evening. He continued, “Well, don’t tell a reporter something you don’t want reported all over the world. That kind of attitude is ruining this community, and you are losing your place as moral leaders of this community.”

Then the young men’s bodies were found. The FBI made eighteen arrests that year, but state prosecutors refused to try the case, claiming lack of evidence. That period—1964— was called “the troubles,” which meant you didn’t talk about it. And everything went quiet until about two years after that.

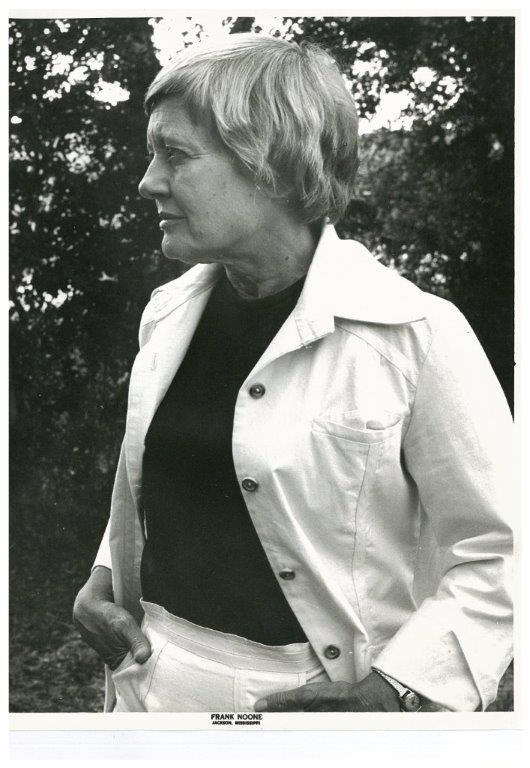

In 1966, Florence Mars, a strong supporter of civil rights, spoke out. A White woman, she owned the stockyards and was from a very prominent family in Philadelphia. Florence and her sister worked with the FBI during the investigation of the Philadelphia murders. Well, once, when she and her sister had been at the Neshoba County Fair and had had a few drinks—as happens at the Fair— they were driving back to Philadelphia, when Sheriff Lawrence Rainey and Deputy Sheriff Cecil Price pulled them over. Now, during that time, if you found someone in that condition—a lady—you drove her home. But instead of driving them home, they threw Florence and her sister into the drunk tank, in jail. They were left there and denied a phone call. Well, all of a sudden, the sheriff’s department had stepped over the line. Apparently, you could burn churches and beat or kill people, but you could not leave someone from our class—the White class—in the drunk tank without a phone call. Community members met that Sunday night, and they called Rainey and Price and said, “We are not going to have this. You guys are no longer in charge. Step down.” That eased things, but a year later the Klan kept shooting into the school superintendent’s home, and he committed suicide from the pressure. Those two events changed things. No private schools sprang up after integration, for instance, and there were other changes. But going through that—for me, it was a lesson: in times of crisis, your actions matter, and if you step back, then others—in this case, the bullies, the dirt road terrorists—run the show. It was an important lesson.

Years after the killings, this community still bore the shame of the murders. Martin Luther King, Jr., visited in 1966. He was marching up the hill; there were bottles being thrown at him, and people were cursing. A guy jumped off the back of a pickup truck and hit Ralph Abernathy. It was just chaos, and I was watching all of this. Florence Mars was there; she stood there by herself and held an American flag as they marched up the hill—a small act, but a heroic act. African American preachers—some of the real heroes—marched up Beacon Hill that day in 1964 with Dr. King and John Lewis, side by side. I thought those guys were crazy, the local guys. So I got to see real heroism at a young age from some folks who had never imagined that they would be putting their very lives on the line. I heard King tell the townspeople, “There is a complete reign of terror here.” He was standing with a group of people, about fifteen people, and he said, “This is the worst place I’ve ever been in my life. The killers of those young men are within the sound of my voice.” And somebody said, “You damn right,” from back about three or four rows. I’m almost sure I know who said that, and he was one of them.

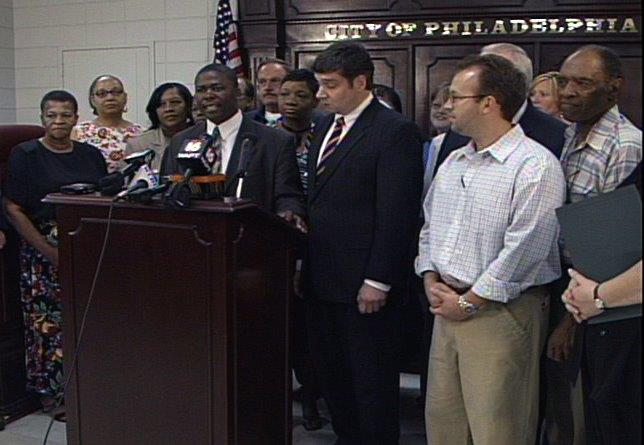

Now: redemption. Growing up, I could see that people had a view of Philadelphia as the hell hole of the world. Finally, in 1989, the leaders of the town said, “You know, we should apologize to the families about the deaths of their three children.” There was a growing recognition that some things needed to be set right. But things don’t move very quickly in Mississippi, as we know. In 2004, there was a coalition founded, called the Philadelphia Coalition. It was made up of Choctaw Indians, African Americans, and Whites. About thirty people came together, prominent people and not-so-prominent people, people from all different walks of life. Some of them had never met each other, either, because, although they lived within a block or a half block of each other, they were in separate communities. They began a push for justice. They brought the mother of Andrew Goodman down, and the mother of James Chaney. The newspaper featured a shot of Mrs. Goodman and her son Andy, with her holding up his baseball card collection, which turned him into a human being to the public. Mrs. Chaney talked about her son, J. C., and Rita Schwerner, the widow of Mickey Schwerner, came. The Coalition invited Attorney General Jim Hood to come to Philadelphia, as well as the local district attorney. Of course, Clarion Ledger reporter Jerry Mitchell was into his “relentless” mode, popping out stories regularly. In 2004, that community came together: 1,500 people representing a clear and direct call for justice.

In the final resolution, a jury was picked from Neshoba County. The ring leader of the murders of those young men was indicted and was convicted of three counts of manslaughter, a twenty-year term for each to be served on top of each other. He was convicted on June 21, 2005, forty-one years to the day that those three young men were kidnapped and killed. A number of us in this room were in Philadelphia at the fiftieth anniversary at Mount Zion Church, where this started. I was sitting there, former SNCC chair Senator John Lewis was the speaker, and I was looking at a racially mixed community of people, most of whom were from my hometown. The mayor of Philadelphia, a majority-White town, was an African American man. He stood up and said, “I know that a lot of you in the past have been worried about being thrown in jail when you came through Philadelphia.” Then he said, “I’m the mayor. I’ll get you out.” That was a new day, and to me some type of redemption.

Now, I don’t mean to say that there is any kind of utopia now in Neshoba County; there is still anger, hate, and evil. I don’t know that it will ever change, but I’ve just been so blessed to watch the arch of history in my hometown. Spun out of the Philadelphia Coalition was the Neshoba Youth Coalition, which is working on the issues that put young people into poverty, addressing teen pregnancy rates, improving school test scores. I am not sure where it is going to go, but if it continues to work, then Philadelphia is going to become one of the lighthouses in this country after being one of the darkest spots. So I feel very fortunate to have seen that arch of history and to see where it is today.

Of course, the real heroes of this whole story were the young people, the Freedom Summer volunteers who came and fell in behind the wonderful leaders. You know, we had heard in 1963 that the communists were coming to Neshoba County. As a young boy, I could hardly wait because I had never seen a communist. When I watched that first march come up the hill, I was really disappointed, because I thought that they just looked like college kids, which they were. There was a lot of heroism. But from the middle-class White community, there were only about fifteen or twenty heroes, and they paid the price.

Dick Molpus served as secretary of state of the State of Mississippi for three terms spanning 1984-1995. On the twenty-fifth anniversary of the murders, he delivered the first public apology to the families of James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael “Mickey” Schwerner at an ecumenical memorial service held at Mount Zion Church in Philadelphia, Mississippi. Molpus was later honored as a Champion of Justice by the Mississippi Center of Justice in 2008 and was also recognized in 2014 during the fiftieth anniversary of Freedom Summer in Philadelphia for his instrumental role in helping to foster racial justice and reconciliation in the state of Mississippi. Molpus is president of The Molpus Woodlands Group, a timberland investment management organization headquartered in Jackson, Mississippi, and also serves as a board member of the New York City-based Andrew Goodman Foundation, which focuses on voting rights and justice issues

-

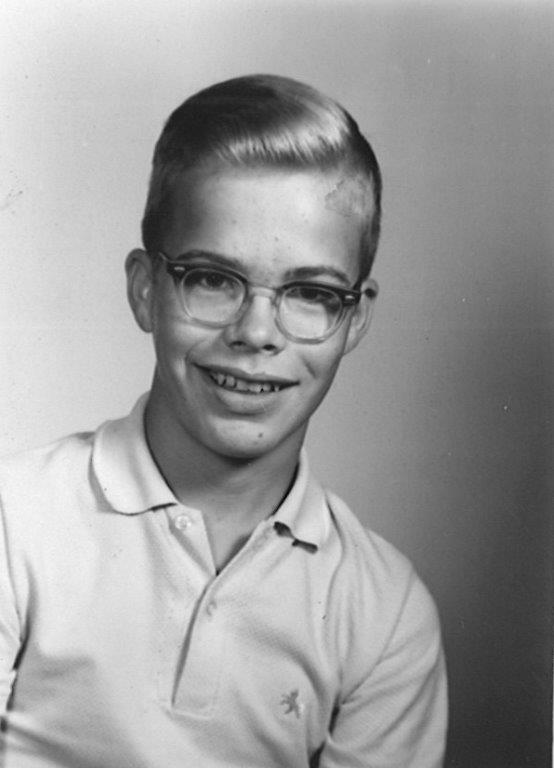

David Goodman holds a rock from the site where his brother, Andrew Goodman, along with James Chaney and Michael Schwerner, was murdered fifty years previously. Courtesy of The Andrew Goodman Foundation. -

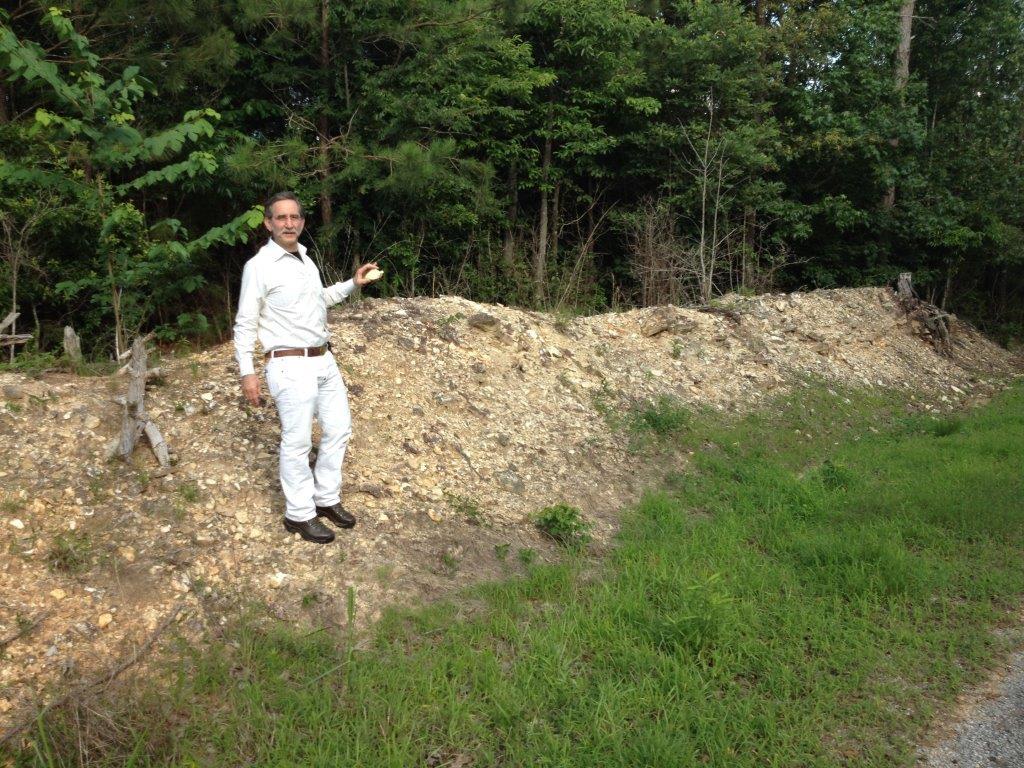

Martin Luther King, Jr. holds photos of the three civil rights workers. Courtesy of The Andrew Goodman Foundation. -

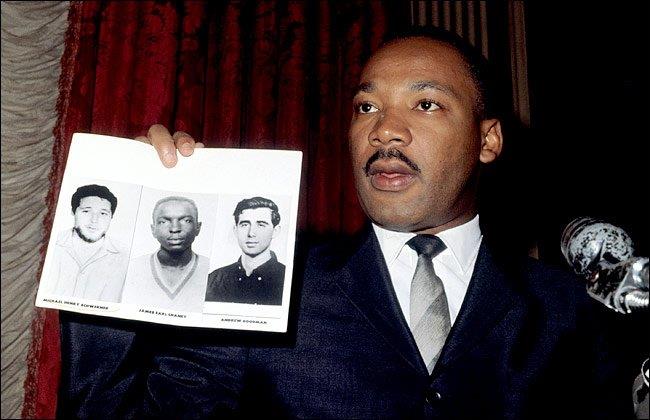

The mothers of the three slain civil rights workers, Fannie Lee Chaney, Carolyn Goodman, and Anne Schwerner, leave the Meeting House at the Society for Ethical Culture, New York, New York, where funeral services were held for Andrew Goodman. Courtesy of The Andrew Goodman Foundation. -

Florence Mars, civil rights activist and author of Witness in Philadelphia. Photograph taken by photographer Frank Noone, Jackson, Mississippi. Courtesy of Deville Camera & Video. -

Philadelphia Coalition makes its "Call for Justice" speech in May of 2004. Courtesy of the Philadelphia Coalition. -

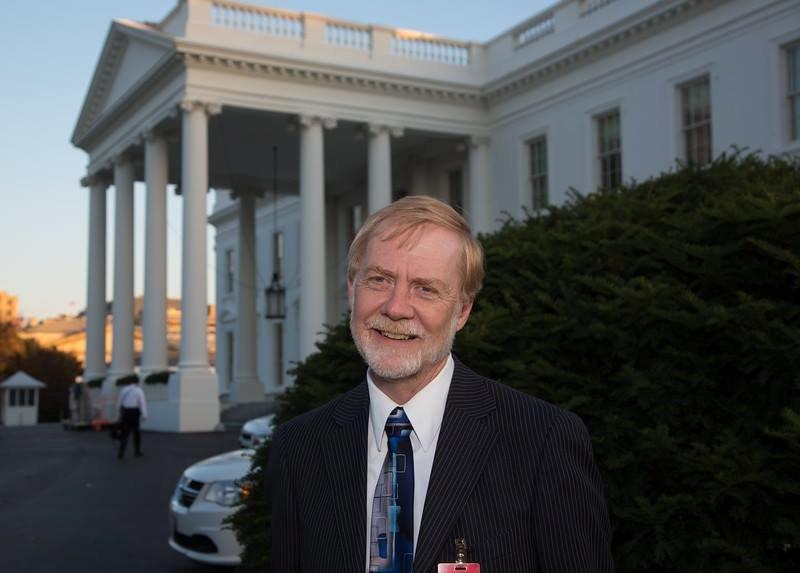

Jerry Mitchell, investigative reporter for the Clarion-Ledger, was instrumental in helping to reopen the 1964 civil rights murders in Philadelphia. This photograph of Mitchell was taken on November 24, 2014, following the awarding of the Presidential Medal of Freedom to each of the families of James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner. Courtesy of Jerry Mitchell. -

Photograph taken on June 15, 2014, at Mount Zion Church during the fiftieth anniversary of the civil rights murders in Neshoba County. On the front row from left to right: Bob Moses, Dave Dennis, Rita Schwerner Bender, Leroy Clemons, Myrlie Evers, John Lewis, Deborah Posey, and Jewel McDonald. Dignitaries identifiable on the second row: William Winter (behind Rita Schwerner Bender), David Goodman (behind John Lewis), and Angela Chaney Lewis (behind Deborah Posey). Courtesy of The Andrew Goodman Foundation. -

Memorial to slain civil rights workers on the grounds of Mount Zion Church, Neshoba County, Mississippi. Courtesy of The William Winter Institute for Racial Reconciliation. -

Postcard sent by Andrew Goodman to his parents upon his arrival in Meridian, Mississippi. It was postmarked on June 21, 1964, the date of his death in Neshoba County. Courtesy of The Andrew Goodman Foundation.

Suggested Reading:

Documents

Molpus, Dick. “Remarks by Secretary of State Dick Molpus.” Speech, Philadelphia, MS, June 21, 1989. Philadelphia Coalition. http://www.neshobajustice.com/pages/molpus89.htm

Philadelphia Coalition. “Call for Justice.” Speech, Philadelphia, MS, May, 2004. Philadelphia Coalition. http://www.neshobajustice.com/pages/2004mem.htm

Videos

Dickoff, Micki, and Tony Pagano. Neshoba: The Price of Freedom. DVD. New York: Firstrun Features, 2010.

William Winter Institute for Racial Reconciliation. (2004, May). Neshoba County – Philadelphia News Conference 04 [Video file]. Retrieved from http://vimeo.com/album/1669695/video/27776667

Books

Cagin, Seth, and Philip Dray. We Are Not Afraid: The Mississippi Murder of Goodman, Schwerner, and Chaney – The Dramatic Story That Shocked the Nation. New York: Macmillan Publishing Company, 1988.

Dittmer, John. Local People: The Struggle for Civil Rights in Mississippi. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1994.

Mars, Florence. Witness in Philadelphia. Baton Rouge: LSU Press, 1989.

Marsh, Charles. God’s Long Summer: Stories of Faith and Civil Rights. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1997.

Payne, Charles M. I’ve Got the Light of Freedom: The Organizing Tradition and the Mississippi Freedom Struggle. Oakland: University of California Press, 2007.

Websites

The Andrew Goodman Foundation, http://andrewgoodman.org/

The Philadelphia Coalition, http://www.neshobajustice.com/

The William Winter Institute for Racial Reconciliation, http://winterinstitute.org/