In the early twentieth century, Black people in Mississippi who aimed to exercise their rights as citizens of the United States had few allies. State and local government officials, acting under the authority of the 1890 state constitution, blocked efforts by black citizens to vote and operated separate schools for White and Black children. In other states, by the 1930s, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) had developed a strategy to gain full citizenship rights: use the courts. What NAACP lawyers argued, on behalf of Black citizen clients, was that rights guaranteed in the federal constitution could not be taken away by state or local laws. Though this strategy was starting to bear fruit in cases such as Smith v. Allwright, in which the Supreme Court in 1944 overturned a Texas law that allowed for Whites-only primary elections, it was slow to blossom in Mississippi.

Bringing cases like those the NAACP was pursuing elsewhere required at a minimum two willing parties: a person, or people, denied constitutional rights and a lawyer. In Mississippi, where retaliation against efforts by Black people to claim basic rights could include job loss, eviction, beatings and, in some cases, death, it was not easy to find an aggrieved person who could withstand the pressure. It was even harder to find a lawyer. As the 1950s drew to a close, there were only four Black lawyers in the state and only three of them, R. Jess Brown, Carsie Hall, and Jack Young Sr., were willing to take on civil rights cases. Only one White Mississippi lawyer, William Higgs, a 1955 Harvard Law graduate from Coahoma County, would pursue such cases.

In 1958, Mississippi's first NAACP-backed voting rights case was filed in Jefferson Davis County on behalf of Reverend H. D. Darby, a Black minister from Prentiss, and other Black residents in the county who had been prevented from registering to vote. Darby and the other plaintiffs were represented by Brown and three attorneys for the New York–based NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund (LDF)—Thurgood Marshall, Constance Baker Motley, and Robert L. Carter. Mississippi, like many states, required that at least one lawyer involved in a case be licensed in the state where the court was located. In agreeing to participate in the Darby case, Brown faced possible disbarment and criminal prosecution under a state law, later determined to be unconstitutional. In a transparent effort to thwart cases supported by the NAACP, state legislators had passed a law prohibiting lawyers licensed by the state from “accepting fees from individuals or organizations, for the purpose of filing suits to change the policy of the state.”

The dearth of Black lawyers was itself a result of Mississippi’s White supremacist history. The only public law school in Mississippi, at the University of Mississippi in Oxford, did not admit Black students until 1963. Lawyers who had graduated from “Ole Miss” law school had the privilege of admission to the bar without having to pass the state’s bar exam. The only private law school in Mississippi, the then-named Jackson School of Law, remained segregated into the 1970s. Brown had attended Texas Southern University Law School. Hall and Young were mail carriers for the United States Postal Service, who had “read” law as apprentices under the supervision of Sidney Redmond, a Black Harvard Law graduate who practiced primarily in St. Louis, Missouri. Young and Hall passed the Mississippi bar in 1951 and 1954, respectively.

One or more of these four lawyers–Brown, Hall, Higgs and Young–were often paired with out-of-state lawyers in the early high profile civil rights cases in Mississippi: the defense of Mack Charles Parker, accused of raping a White woman and lynched while awaiting trial (1959); the defense of Clyde Kennard on trumped-up theft charges after he applied repeatedly to integrate Mississippi Southern College (1959); the defense of Freedom Riders arrested for entering segregated waiting rooms and restrooms in bus stations in Jackson (1961); and James Meredith’s suit challenging the University of Mississippi’s Whites-only admission policy (1962). “In the very beginning, an out-of-state lawyer, even though he was a lawyer, he could not practice,” Hall recalled during a 1979 panel discussion at Tougaloo College. “We would have to take it to court, you know, and introduce him, and then he would have his say. Just (four) lawyers, you know, we couldn’t take lawyers all over the state. So you see how people were hemmed in.”

The more civil rights activists pressed their case for citizenship rights in Mississippi, the more the state power structure pushed back. Between 1954 and the early 1960s, the Mississippi Legislature passed a series of laws aimed at protecting White supremacy, including “a sweeping ‘breach of the peace’ statute making it a crime to advocate, urge, or encourage ‘disobedience to any law of the State of Mississippi, and nonconformance with the established traditions, customs, and usages of the State of Mississippi.” (Dittmer) This led to arrests on a massive scale—sometimes hundreds a day in multiple towns—and it became clear that Mississippi’s civil rights activists were going to need more lawyers. “This was a crisis of whether or not there was going to be a constitution in this country … and what was required was the direct legal intervention of the people themselves, with their own lawyers,” recalled Arthur Kinoy, a New York lawyer who worked extensively in Mississippi. The role of lawyers, he argued, was “helping to lift the power of the power structure from your back so you can solve the fundamental problems, and move forward in your struggle.”

In addition to the NAACP LDF, three other national organizations—the National Lawyers Guild, the Lawyers Committee for Civil Rights Under Law, and the Lawyers' Constitutional Defense Committee—sent lawyers to Mississippi, and all four eventually opened offices in the state. Each organization had slightly different priorities and developed expertise in specific areas. The Lawyers Committee for Civil Rights Under Law, for example, was formed in 1963 after President John F. Kennedy convened a meeting of 244 lawyers in the White House and asked private lawyers to lend their expertise to the struggle. Kennedy’s hope was that confrontations between protesters and state officials could be shifted from public view and into the courts. Hundreds of lawyers answered the call to be “missionaries to the bar” in Mississippi, some spending their two-week vacations, some much longer to push for civil rights through the law.

Moving the civil rights battle into the courts in Mississippi, however, did not initially bring much relief. Whether defending against a ‘breach of peace’ in criminal court or seeking the right to register to vote in a civil case, lawyers found little justice in the state court system. Mirroring the political structure, Mississippi’s courts were also defenders of White supremacy. White prosecutors pressed serious charges, White jurors voted to convict, and judges handed down sentences and levied fines. Facing such a monolithic state response, the out-of-state lawyers needed a way to get their cases heard in federal court, where they could appeal to rights guaranteed in the U.S. Constitution. To do so, they revived a Reconstruction-era statute, the Civil Rights Act of 1866, which allowed defendants who alleged they could not enforce their equal rights in state court to file a removal petition to transfer a case to federal court.

The removal strategy is just one example of the creative thinking the civil rights lawyers in Mississippi used to relieve the pressure on civil rights activists. Lawyers such as Marian Wright Edelman, Mel Leventhal, and Frank Parker also did the tedious, years-long work of developing the arguments that led to landmark decisions from the U.S. Supreme Court in the areas of school desegregation (Alexander v. Holmes) and voting rights (Connor v. Johnson). Lawyers and law students fanned out across the state to collect affidavits to document the myriad ways state, local, and political party officials prevented Black citizens from voting. This work was critical in passage of the Voting Rights Act and in litigation for its enforcement.

In 1967, another type of lawyer joined the fight. Reuben Anderson, the first Black graduate of the University of Mississippi Law School, began his career at the Mississippi office of the NAACP LDF. One year later, he was joined at LDF by another Mississippi native, Fred Banks, who had graduated from Howard University Law School. In 1970, Constance Slaughter-Harvey, the first Black woman to earn a law degree from the University of Mississippi, joined the Lawyers Committee for Civil Rights Under Law. Anderson, Banks, and Slaughter-Harvey continued working on civil rights cases, and later moved into the political and judicial arenas that the civil rights movement had forced open: the Mississippi Legislature (Banks, in 1975), the local judiciary (Slaughter-Harvey, 1976), the state Supreme Court (Anderson, in 1985, and Banks, in 1991), and state government (Slaughter-Harvey, from 1980-1992).

The lawyers’ role in the civil rights movement was necessary, but as the lawyers themselves acknowledge, it was not sufficient. The people most essential to the movement were the ones who courageously stepped forward and made the demand for equal citizenship rights. “My greatest appreciation was for our clients,” Banks wrote. “The Reaves and other plaintiffs in Benton County, the Carters in Drew, the Cowans in Bolivar County, the Ayers in Washington County, Rev. Killingsworth, Rev. Barnhardt, the Gladneys, and others who soon followed Medgar Evers and Gilbert Mason and Dovie Hudson and signed on as plaintiffs in search of a better education for their children and their community.”

Sarah C. Campbell is director of programs and publications at the Mississippi Department of Archives and History. She co-wrote the documentary, The Defenders: How Lawyers Protected the Movement.

Media

Lesson Plan

-

Jack Young Sr., pictured second from left, was one of three lawyers who took on civil rights cases in the 1950s and early 1960s. Photo by Richard H. Beadle. -

James Meredith (left) sued the University of Mississippi in 1961 after being denied admission to the school. Meredith was represented by Constance Baker Motley (center), a New York-based attorney for the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, and R. Jess Brown of Jackson. Photo courtesy of The Associated Press.

-

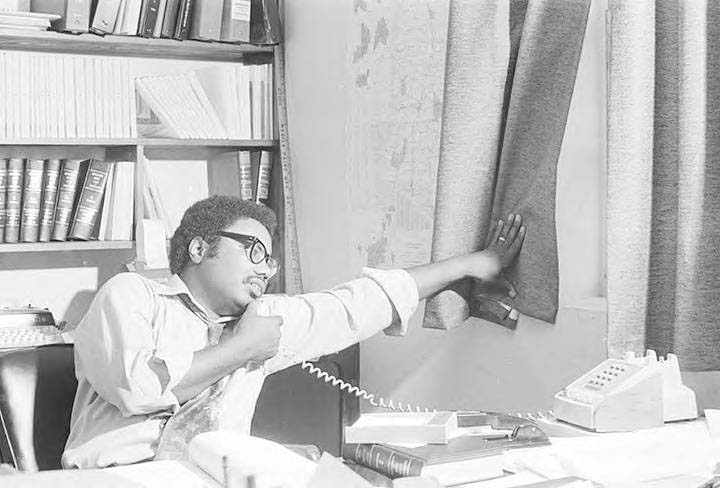

Fred Banks joined the NAACP Legal Defense Fund’s Jackson office in 1968. Photo by Jim Peppler courtesy of the Alabama Department of Archives and History. -

In 1970, Constance Slaughter-Harvey, the first Black woman to earn a law degree from the University of Mississippi, joined the Lawyers Committee for Civil Rights Under Law. Photo by Jim Peppler courtesy of the Alabama Department of Archives and History.

Bibliography

Banks, Fred L. Jr. “Mississippi, Law and the Decade of the 60s,” unpublished paper provided to the writer by the author.

Dittmer, John. Local People: The Struggle for Civil Rights in Mississippi. Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1994.

“History,” Lawyers’ Committee For Civil Rights Under Law, accessed April 14, 2020, https://lawyerscommittee.org/history/.

“National Lawyers Guild,” Digital SNCC Gateway, accessed April 14, 2020, https://snccdigital.org/inside-sncc/alliances-relationships/national-lawyers-guild/.

Parker, Frank R. Black Votes Count: Political Empowerment in Mississippi after 1965. Chapel Hill and London, 1990.

“Pro-Bono Lawyers,” Digital SNCC Gateway, accessed April 14, 2020, https://snccdigital.org/inside-sncc/alliances-relationships/pro-bono-lawyers/.

“Race and the Administration of Justice,” transcript of session held on November 1, 1979, during the “Freedom Summer Reviewed” conference at Tougaloo College. Transcribed by John Jones. MDAH collection.

Spriggs, Kent. Voices of Civil Rights Lawyers: Reflections from the Deep South, 1964-1980. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2017.