Public schooling in Mississippi did not become commonplace until after the American Civil War. After the United States Supreme Court decided in its 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson ruling that states could require separate public facilities for Black and White people as long as they were equal (the so-called “separate but equal” doctrine), White-dominated school boards began concentrating more of their efforts and funding on schools for White children, rather than for Black. By the early 1900s, while many White children studied their textbooks in new functional buildings, Black students were often left to make do in churches, lodges, and poorly constructed buildings that barely kept out the wind and the rain.

Beginning in the 1910s, however, new school buildings for African Americans began to spring up on the Mississippi landscape. The schools, constructed as a partnership between the Julius Rosenwald Fund and local citizens, represented a leap forward for Black southerners who wanted to ensure an education for their children. When the philanthropic program ended in 1932, a victim of the Great Depression, more than 5,000 school buildings had been constructed under its auspices in fourteen southern states. Mississippi’s Rosenwald program constructed six hundred and thirty-three schools and ancillary buildings and was the South’s second-largest state program.

The Rosenwald Fund

The Rosenwald Fund — the product of an alliance between Booker T. Washington, president and founder of Tuskegee Institute in Alabama, and Julius Rosenwald, president and chief executive officer of Sears, Roebuck & Co. in Chicago — was the only philanthropic effort in the early 20th century to concentrate on improving the learning environment of Black students in the South. The fund accomplished this by giving grants to Black communities to cover about a third of the cost of a building. The communities were expected to match the Rosenwald money with either cash or in-kind contributions of labor and materials and to gain financial support from the public school system. While the communities gained a quality building, they also lost a measure of control over their children’s education when the school, which had usually been run by its own board of trustees, came under the control of the county superintendent of education.

Begun at Tuskegee in 1912 and initially focused on the few counties surrounding that campus, the Rosenwald Fund’s fame grew through the extensive personal networks of southern African Americans. By the end of the 1910s, several states surrounding Alabama had a few Rosenwald schools. But after Washington’s death in 1915, Rosenwald lost confidence in the fund’s new leaders at Tuskegee Institute. He moved the fund’s management away from Tuskegee and set up a new office run by foundation professionals in Nashville. During the 1920s, the Rosenwald Fund became increasingly standardized and efficient, approving thousands of grants in all of the southern states.

In Mississippi, only a dozen or so schools obtained help in the early years under Tuskegee’s management. The early buildings were not built to standard plans and often were not much better planned than non-Rosenwald schools. A major shift occurred after the Rosenwald Fund’s reorganization in 1919-1920. By 1922, the Rosenwald Fund reported that one hundred and forty-one Rosenwald schools had been built in Mississippi, including fifty-eight three-teacher schools and five houses for teachers.

A new school building

A primary focus of the newly reorganized Rosenwald Fund was the quality of the construction of school buildings that would be built with its funds. The fund wanted to build as many schools as possible, but it also wanted them to meet current building standards and to be solidly constructed of good materials. Rosenwald also wanted to incorporate knowledge gained during a decade of careful study into lighting levels and ventilation. At the time, rural schools, and even some town schools, did not have electricity to provide lighting or heat. Thus, lighting needed to come into the building through windows, and studies had shown that schools needed many more windows than had previously been thought in order to give students sufficient light. In addition, new research showed that good ventilation prevented the spread of germs and diseases.

Using the findings from a survey of the existing Rosenwald schools by consultant Fletcher B. Dresslar, a recognized authority on the topic of school hygiene and good school planning, the fund, led by its new director, Samuel L. Smith, drew a new set of standard plans that would be used to construct almost all Rosenwald schools in the 1920s. From 1920 onward, the Rosenwald Fund’s emphasis moved from funding “better schools” to encouraging “model schools” that could be standards for both Black and White schools in the South.

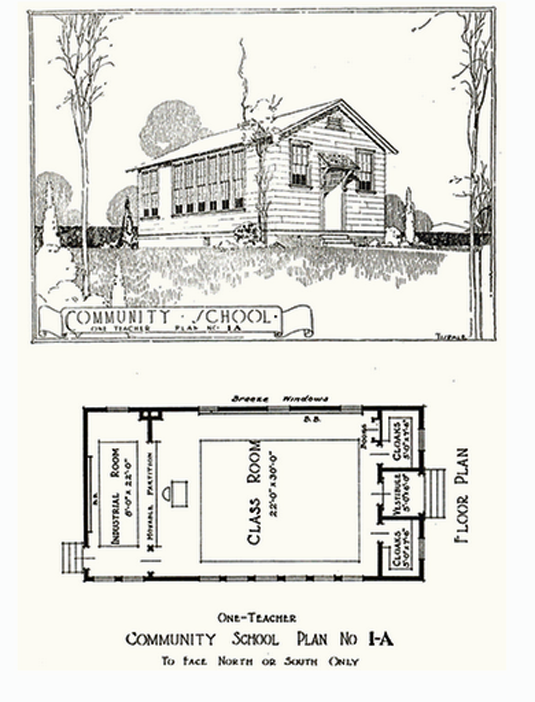

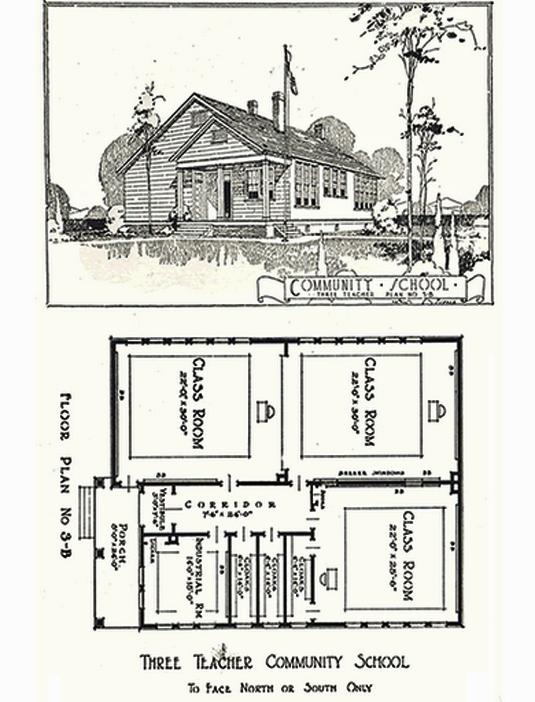

The new plans allowed for a broad variety of schools, based on the number of teachers per school. Ranging from one-classroom structures with a gable front — a common school form in all areas of the country — to large twelve-classroom buildings with auditoriums, the plans relied on simple forms and construction techniques that would be accessible to the many volunteer laborers who built these schools. Several new features of the schools did in fact become models for school architecture in the 1920s, such as:

- One-story construction, which required slightly more land but was easier to build and was considered a safety improvement following several deadly school fires in two-story buildings.

- Large groupings of windows, concentrated on the east and west elevations of buildings, became the hallmark of schools for both Black and White students in the 1920s. Previously, rural school buildings would have a few scattered windows, with windows on several walls of each classroom. Studies showed, however, that light from many directions caused a glare that could damage a student’s eyesight.

- Two school forms, the H-plan and the T-plan, became standard for rural and town schools alike in the 1920s. The Rosenwald standardized plans used these two forms almost exclusively for schools of four classrooms or more. Both plans contained an auditorium for school and community gatherings, but the H-plan was designed to face north or south, with its windows on the sides facing east and west, while the T-plan was designed to face east or west with its windows on the front and back. These simple but effective plans show the ingenuity and flexibility of the Rosenwald Fund’s program and the emphasis on quality even in difficult circumstances.

Out of the original five hundred and fifty-seven schools aided by the Rosenwald Fund in Mississippi, only a relative handful are known to survive (see list below). Of these, about half are either greatly altered or in a deteriorated state. The sole surviving one-classroom school is the Bynum School, built in 1926, in Panola County. Two good examples of the H-plan form are the concrete-block building (1926) at the Prentiss Institute in Jefferson Davis County, a six-classroom building constructed according to Rosenwald Plan #6-A, and the Brushy Creek School (circa 1930) in Copiah County, a clapboard Rosenwald Plan #4-A. The Drew Rosenwald school in Sunflower County began as a substantial T-plan Rosenwald, and grew over the years into a sprawling building with a large student population. The T-plan was especially popular because it could easily handle any needed expansion.

In addition to the known Rosenwald schools, Mississippi has some “ghost schools,” a group of schools that were supposed to have received Rosenwald Funds but the money was fraudulently diverted for personal use between 1923-1928. The Rosenwald agent at the Mississippi Department of Education, Bura Hilbun, who was responsible for overseeing the Rosenwald Fund in Mississippi and sending in final reports to the Nashville office, was later found to have falsified records and pocketed the money meant for certain schools. Hilbun’s fraud was found after he left the education department. He was convicted of embezzlement in 1931 in the Hinds County Circuit Court, after two hung juries. Hilbun appealed to the Mississippi Supreme Court but it upheld the lower court’s decision.

As a result of Hilbun’s falsified records, the historical records of the Rosenwald Fund at Fisk University Archives in Nashville list some schools that were not actually built, thus the “ghost schools.” One of those ghost schools has survived. Poplar Hill School is a rare two-classroom Black school in rural Jefferson County, and while the school appears in the Rosenwald Fund database on the Fisk website, it is not, in fact, a Rosenwald plan and did not receive any Rosenwald funding. This was distressing news to a group of interested alumni who in 2009 pursued a National Register of Historic Places listing for the building as a Rosenwald school. Nonetheless, the building is still significant as a rare surviving rural African-American school, once one of thousands that dotted the Mississippi landscape.

Building school communities

The Rosenwald Fund did not stop with just building new classroom buildings for students. Located in rural areas with poor road systems, the schools came to be somewhat self-sufficient campuses, eventually including not only houses for teachers but also separate buildings for vocational and home economics education.

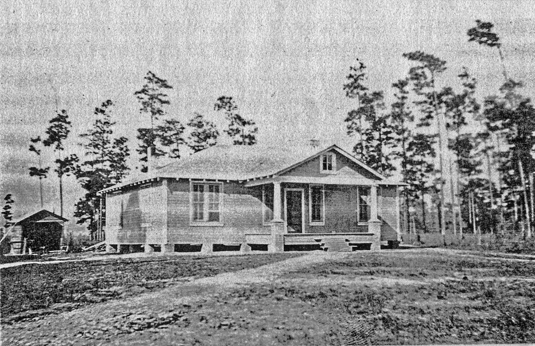

The Rosenwald Fund understood well the challenges of rural schools, and the first and most important one was attracting qualified teachers. School trustees often found it necessary to build a teacher’s house on the campus as a way to entice a principal who could oversee the school’s functioning. Not only did a teacher’s house keep principals and teachers longer at the school, but it provided security for the campus and an on-site alarm in case of fire. As it did with school plans, the fund offered several different house plans for teachers to accommodate families of various sizes. The Rosenwald Fund helped build fifty-eight teacher houses in the state, and many school boards built houses for teachers as well. At least two of the Rosenwald houses still stand in the state, the John White School teacher’s house (1925) in Forrest County and the former president’s house (circa 1930) at Coahoma Community College north of Clarksdale, a campus that began as one of only two agricultural high schools for African Americans. The other school was Hinds County Agricultural High School in Utica (1946).

Vocational buildings or shops were also seen as a way to improve both the campus and the school’s educational program. The Rosenwald Fund emphasized vocational education not only because of its origins at Washington’s Tuskegee Institute but because training in agricultural and mechanical skills was thought to be the best way to educate rural children of both races for much of the first half of the 20th century. Indeed, backed by sufficient funding, white consolidated schools of the same period far outstripped Black schools in providing buildings and teachers for vocational and home economics education and were considered better schools because of it. Only eighteen vocational buildings for Black schools were constructed in Mississippi under the Rosenwald program, primarily because of a lack of matching funds and because building a vocational building also meant hiring an extra teacher to teach the classes. This was often out of reach for the Rosenwald schools, struggling to survive on limited funding from the public school boards.

By 1932, two years after Rosenwald’s death and three years after the stock market crash slashed the value of its endowment, the Rosenwald Fund ceased its building program, leaving southern African Americans and southern progressives to find another solution for Black education.

Jennifer Baughn is an architectural historian at the Mississippi Department of Archives and History. This article was updated in September 2021.

Rosenwald Schools Known to Survive in Mississippi

- Bynum School, Panola County (1926)—Plan #1-A.

- Drew School, Sunflower County (1929)—T-plan, by architect James M. Spain, using Plan #5 as the basic floor plan.

- Pass Christian (Randolph) School, Pass Christian, Harrison County (1928)—U-plan, not a standardized Rosenwald plan, unknown architect.

- Brushy Creek School, Copiah County (c.1930)—Plan #4-A (H-plan).

- Prentiss Institute, Prentiss, Jefferson Davis County (1926)—Plan #6-A (H-plan).

- Sherman Line School, Amite County (1928)—Plan #3-B.

- Hollandale School, Washington County (1924)—T-plan, only a section survives and is extensively altered.

- Nichols Elementary School, Canton, Madison County (1927)—Plan #7 (T-plan).

- Bay Springs School, Forrest County (1925)—Plan #20 (this is the only remaining building of this most popular two-classroom plan known to survive in the state. Vernon Dahmer, the civil rights leader slain in a house bombing, lived adjacent to this school and served on its board of trustees).

- Pantherburn School, Sharkey County (1927)—Plan #400 (now a church and altered).

- Walthall County Training (Ginntown) School, Walthall County (1920)—Plan #400.

- Marks School, Quitman County (1922)—not a standardized plan.

- Swiftown School, Leflore County (1921)—not a standardized plan, not clear whether this is actually a Rosenwald school.

- Oak Park Principal’s Home and Girls Dormitory, Laurel, Jones County (1928)—not a standardized plan.

- John White School Teacher’s House, Forrest County (1925)—Plan #302.

- Faculty House #1, Coahoma Agricultural High School (now Community College) (1931)—Plan #302.

- Former Girls' Dormitory, Coahoma Agricultural High School (now Community College) (1931)—Plan 6-A variant.

- Moorhead School Teacher’s House, Sunflower County (1932)—Plan #301.

- Terry Rosenwald School, Hinds County (1924)—Plan #20.

-

Built in 1926, the Bynum School in Panola County is the only surviving one-classroom Rosenwald school in Mississippi. Photograph by Jennifer Baughn. Courtesy Mississippi Department of Archives and History. -

Rosenwald plan for a one-teacher school. Courtesy Julius Rosenwald Fund, Community School Plans, Bulletin No. 3, Nashville, Tennessee, 1924.

-

Philanthropist Julius Rosenwald (1862-1932) established the Rosenwald Fund to improve the learning environment for southern black students in the early 20th century. Date of photograph unknown. Courtesy Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, LC-B2-4552-18. -

Brushy Creek School, 1930, in Copiah County, Mississippi, is an example of the Rosenwald H-plan form. Photograph by Jennifer Baughn. Courtesy Mississippi Department of Archives and History. -

Rosenwald plan for a three-teacher school. Courtesy Julius Rosenwald Fund, Community School Plans, Bulletin No. 3, Nashville, Tennessee, 1924. -

Sherman Line School in Amite County, Mississippi, built in 1928. Photograph by Jennifer Baughn. Courtesy Mississippi Department of Archives and History. -

Rosenwald school at Bay Springs (1925) is the only two-classroom plan known to survive in Mississippi. Photograph by Jennifer Baughn. Courtesy Mississippi Department of Archives and History. -

The John White teacher's home in Forrest County, Mississippi. The Rosenwald Fund often found it necessary to build a teacher's house on campus to attract qualified teachers. Photograph used by permission of The Fisk University Franklin Library, Special Collections. -

Built in 1926, the concrete-block Prentiss Institute in Jefferson Davis County, Mississippi, is a six-classroom building in the Rosenwald H-plan form. Photograph by Jennifer Baughn. Courtesy Mississippi Department of Archives and History.

References:

Hoffschwelle, Mary. Rosenwald Schools in the American South. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2006.

“Rosenwald Rural School House Construction to February 1, 1922,” Julius Rosenwald Fund Collection, Box 331, Fisk University Archives, Nashville, Tennessee.