Without question, Sarah Anne Ellis Dorsey was one of the most intellectually gifted women of Mississippi. With considerable aplomb, she dealt as best she could with the emotional tensions arising from her lifelong compulsion to balance the conventional female role of the plantation South with a more rigorous life of the mind. Her heart and soul refused to submit to all the repressive demands that held women in a virtual prison, called hearth and home. But finding a proper balance between these polarities in the 19th century was scarcely easy.

Her heritage, of course, was a factor in shaping her future as a novelist, biographer, and friend of significant men of mind whom she entertained at home and abroad. Her father was Thomas George Percy Ellis, a planter in Natchez, Mississippi, who had studied at Princeton University and had few ambitions, but loved books and intellectual discussion. In 1828 he had wedded Mary Malvina Routh, a pretty and fashionable belle of only fifteen who belonged to a wealthy Natchez family. Born in 1829, their daughter Sarah was her serious-minded father’s joy. She loved him far more than she did her predictably tradition-bound mother. The Ellis household included her grandmother, a Percy, who, like others in the Percy family, suffered from severe, sometimes suicidal, depression. The sad state of the grandmother’s psychosis was to figure in some of Sarah’s novels.

Educating Sarah

The early death of her father and his enormous debts nearly drove Mary Routh Ellis and Sarah into the poorhouse — but for her mother’s fortuitous remarriage to financier Charles Gustavus Dahlgren. Dahlgren managed to rescue the family and provide for Sarah’s education. Dahlgren was quite an admirer of Sarah’s mind, and even when the family finances seemed most forbidding, he managed to send her to the French schoolmistress Madame Deborah Grelaud in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Gifted as she was in art, dance, and music, she excelled in her studies and showed even greater proclivity with languages, gaining fluency in French, Italian, Spanish, and German. Sarah’s stepfather also had her trained in law and bookkeeping – scarcely typical subjects for a woman in mid-19th century America.

At Madame Grelaud’s, her favorite instructor and closest friend thereafter was Anne Charlotte Lynch, who later married Vincenzio Botta, a New York University professor. From the 1840s onward, Anne Lynch Botta assembled a French-like salon for recognized thinkers. Among her guests were William Cullen Bryant, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Julia Ward Howe, Herman Melville, and Catherine Sedgwick, and, from England, Charles Dickens, Anthony Trollope, and Charles Kingsley. Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Raven,” was first presented in her rooms. The salon encouraged Sarah to do likewise but in distant Natchez, much to the ridicule of the local ladies. “She tries[,] poor girl[,] so hard,” sneered one of them, “to be thought fashionable.”

In 1852 at age twenty-four, Sarah married into a distinguished Maryland family of jurists. Samuel Worthington Dorsey, age forty-two, was no doubt attracted to her intellectual vivacity, wit, and, truth be told, her considerable wealth. Dorsey had started as a struggling Vicksburg attorney but became a manager for the Dorsey and Routh plantations in Tensas Parish, Louisiana. He was no intellectual but a man of business, popular with his hunting and fishing neighbors. In the South of that era, Sarah could scarcely have found a male with comparable talents to her own. Stepfather Dahlgren was disappointed in her choice. “It was like wedding the living to the dead,” he tactlessly told the bride.

When the American Civil War began in 1861, the lavish entertainments and dinners at the Dorsey’s Elkridge estate in Louisiana came to an end. Sarah Dorsey, though an anti-secession Whig like her wealthy kinfolk and neighbors, plunged with gusto into work she thought patriotic. The ideals of military honor greatly appealed to Sarah. Her favorite soldier of glory was the Right Reverend Leonidas L. Polk, bishop of Louisiana, a Confederate brigadier-general, and former West Pointer. The war, however, was no romantic adventure.

The romantic literary tradition

In 1863, after some of Union General Ulysses S. Grant’s troops had burned her Elkridge mansion to the ground, Sarah and Samuel Dorsey led a hundred enslaved people to lands in East Texas. It was in the midst of working at a Confederate hospital that Sarah Dorsey began her literary career. No doubt it was a means of escape from the ugly realities of war, the stench of the rotting cadavers, and the devastation of all that once had been taken for granted. Her first work of fiction was Agnes Graham, published in serial form (1863-1864) in a Southern literary magazine. It is a fantasy about happier times in the upper ranks of Southern society, and like her other novels, it was barely disguised autobiography.

Sarah Dorsey’s second and far more literary work was a biography of her close friend Henry Watkins Allen, a wartime governor of Louisiana, published in 1866. Women were supposedly ill-equipped to write biographies of politicians or indeed of any male. She was one of the few to successfully break the convention. Like Bishop Polk, Allen admired women of mind, and she reciprocated with this well-written account of Allen’s Whiggish career. Dorsey’s prose had a certain liveliness and freshness that is quite surprising. Moreover, she used the biography to explain women’s indispensable contribution to the war effort, and to elaborate on the hidden talents that the plantation women had revealed in their various tasks out of wartime necessity. All in all, this work was among the first to help create that curious postwar movement that mixed legend, mourning, and anger – the “Lost Cause” legend that would continue to dominate Southern memory over the next fifty years or more. That cultural movement, as well as Dorsey’s sentiments, was a way for postwar Southern White men and women to reconcile themselves to undeniable Union conquest yet find inspired meaning in that humiliation.

Dorsey’s creative skill and compelling intensity with words were evident in her next work, a fictionalized narrative about the flight from Louisiana to Texas. Among the many painterly scenes in Lucia Dare (1867), she describes the lush scenery of that lengthy journey. Critics slammed it. They complained of its harsh realism about the deprivations, hunger, and weariness of those enslaved and their masters. Perhaps chastened, her next effort, Athalie (1872), concerns women undertaking work to aid the poor. Panola (1877), a far more popular fiction, dissects the faults and weaknesses of the Louisiana elite. Dorsey published with reputable Philadelphia houses, but how well they fared in the marketplace is hard to say.

Accumulating friends abroad

For all the frustrations that the Dorseys endured with their dislike of postwar Republican federal and state rule, they still enjoyed a large income. It permitted them to escape abroad. Thanks to her friend and mentor Anne Botta’s introductions, Sarah met a number of English notables. She particularly enjoyed a stimulating intellectual relationship with the truculent Lady Henrietta Maria Stanley, an ardent feminist who founded Girton College, Cambridge. Sarah had hoped to meet the Oxford philosopher Benjamin Jowett, but Lady Stanley instead hustled her off for tea at the residence of Thomas Carlyle, the renowned critic of modern middle-class vulgarity. To Sarah’s delight, Carlyle gave her an hour and half diatribe on transatlantic middle-class imperfections.

Even more important to her than association with Lady Stanley was the friendship of Edward Lyulph Stanley, who had matriculated at Oxford, kept up lively interests in literature and the arts, and knew most everyone of high intelligence in the otherwise dullish upper-class landowners.

Sarah also grew fond of Anna Leonowens, later famed as the governess and heroine in Margaret Landon’s Anna and the King of Siam (1944). Through her, Sarah Dorsey discovered the mysteries of the Buddhist, Hindu, and Islamic faiths. Sarah became exceedingly devoted to Hinduism. On return to New Orleans, she gave a public lecture on the “noble Aryans” of India and their philosophy. She remained, however, a devout Episcopalian.

As Sarah Dorsey aged, she became more restless in her role as a woman of leisure. While remaining basically faithful to the Southern female code, she thought of heading a girls’ school in Maryland. She came, however, to realize that acceptance of headmistress would mean a rejection of her father’s values and a surrender to the temptations of independence. Her husband, and also, surprisingly, the liberal-minded Lyulph Stanley, disapproved of her taking the position. Also, she felt educationally inadequate. Her education at Madame Grelaud’s was no preparation for advanced study. Sarah protested to Stanley that he could lecture here and there, attend functions at his Balliol College and converse with the Oxford dons such as Benjamin Jowett. But what could she do? “What must I read, what training must I individually go through, in order to escape from this fault? … I read the books that Men read but they do not educate me as a man is educated by them. Is it that I do not apply them? & how am I to apply them?” She felt intellectually trapped.

Although growing, feminism was not fully matured and self-confident in mid-19th century England, much less in America. For an antebellum Southern woman to move as far as Sarah Dorsey did was miraculous. Yet, the distance to cultural and artistic equality with men was scores of years in the future.

A new hero

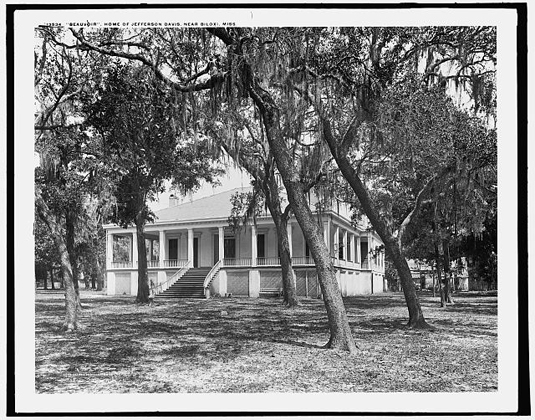

Samuel Dorsey finally ordered an end to his wife’s friendships with Lyulph Stanley, Anne Botta, and Anna Leonowens. Sarah submitted herself to his wishes; he was in weak health and required her constant care. After his death in 1875, Sarah discovered a hero to worship as if she was returning to the enthusiasms for men of glory at the start of the Civil War. Her choice of hero was Jefferson Davis, ex-president of the Confederate States, who helped promulgate the myth of the Lost Cause based on White supremacy. In 1873 she and Samuel had moved to Biloxi, Mississippi, into a pleasant seaside house they called Beauvoir. The widow provided Davis spacious chambers so that he could complete his memoirs. He represented a return for her into the bosom of her progenitors and the conservative mode of life they embodied. Always drawn to vulnerable elderly men, Sarah could both worship Davis as the father she had lost so early in her life and nurse him as the child she had never had. Forgotten were her adventures into a more stimulating life of the mind.

Davis, a chronic depressive, grew dependent on her solicitous nursing, expressions of encouragement, frequent editorial advice about his composition, and her largesse. Varina Howell, Davis’s long-ailing wife, was distraught. She had been Sarah’s classmate at Madame Grelaud’s, but Sarah was now a rival. Local rumors, though false, grew apace over the Dorsey-Davis relationship. Varina returned from her trip to England in 1877 to reclaim her husband. Though at first enraged when visiting Beauvoir, she soon succumbed under the spell of Sarah Dorsey’s gracious hospitality, discretion, and charm.

Not long after Varina’s return to the Davis home in Memphis, Sarah Dorsey was apprised of a fatal disease. Her breast cancer required surgery in New Orleans, but it was unsuccessful. In this state of affairs, Sarah Dorsey decided to leave all her property to Jefferson Davis, a gentleman “who in my eyes,” she wrote, is “the highest and noblest in existence.” Completely estranged from all the Dahlgren kinfolks, she allotted them not a dime of her fortune even though some swayed close to the edge of poverty. At age 50, she died on July 4, 1879, at the St. Charles Hotel in New Orleans.

Her final decision to reward the leader of a lost cause that spelled ruin of all she held dear in the old regime was almost tragic. Yet, within the constrictions of the “Southern way” she had made a contribution that few other women of her class in the Old South could have earned. For all her faults and her stubborn loyalty to Southern custom, she can be recognized for her remarkable resilience and her wholehearted quest for knowledge.

Bertram Wyatt-Brown, Ph.D., is the Richard J. Milbauer Professor Emeritus at the University of Florida and Visiting Scholar, Johns Hopkins University.

-

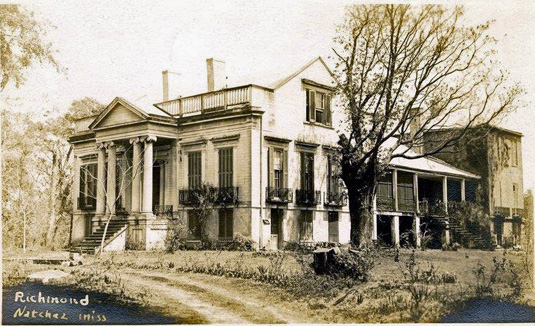

Richmond, the town dwelling of Thomas George Percy Ellis and Mary Routh Ellis in Natchez, Mississippi. Their daughter, Sarah Anne Ellis, was born here in 1829. Courtesy Mississippi Department of Archives and History, Cooper Postcard Collection, PI/1992.0001. -

Sarah Anne Ellis Dorsey (1829-1879), novelist and biographer from Natchez, Mississippi. Courtesy the Beauvoir House.

-

Site of Ellis family’s home, Routhlands, in Natchez, Mississippi, which had “columns and upper galleries on both sides.” The original house burned in 1855 and this house was built in 1856 on the site (later owners named it Dunleith). Courtesy Mississippi Department of Archives and History, Cooper Postcard Collection, PI/1992.0002. -

Thomas George Percy Ellis (1805-1838), beloved father of Sarah Anne Ellis Dorsey. Used by permission of Telfair Academy of Arts and Sciences, Inc., Savannah, Georgia. -

Mary Routh Ellis Dahlgren (1813-1858), mother of Sarah Anne Ellis Dorsey, and wife of Thomas George Percy Ellis and of Charles Gustavus Dahlgren. Used by permission of Telfair Academy of Arts and Sciences, Inc., Savannah, Georgia. -

Beauvoir, home of Sarah Dorsey on the Mississippi Gulf Coast, which she bequeathed to Jefferson Davis. Courtesy Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, LC-D4-13534.

Further reading

Wyatt-Brown, Bertram. The House of Percy: Honor, Melancholy and Imagination in a Southern Family. New York: Oxford University Press, 1994.