During Reconstruction, one of the most turbulent periods for race relations in the state’s history, Sarah Ann Dickey, a White female teacher from the North, became a pioneer by providing education to newly freed enslaved people in Mississippi. Dickey worked tirelessly and determinedly to improve the lives of the most vulnerable population group in the state, African American women and children. She believed that by educating Black women and training them to become teachers, dual paths of security and opportunity could be established for all freedmen. Ultimately, Dickey proved to be one of a small, but remarkable group of individuals who doggedly and determinedly pressed for vital, local changes in hopes of promoting racial harmony in post-Civil War Mississippi.

Dickey was born in 1838 in rural Ohio. Her mother died in 1846 when she was only eight years old, and her father sent her to live with an aunt who also resided in Ohio. By age thirteen, Dickey had received no formal education or religious training. At age nineteen, she received a teaching certificate and began her teaching career. She joined the Church of the United Brethren in 1858.

Dickey was teaching in Ohio when the American Civil War began in 1861. After the Emancipation Proclamation effectively freed enslaved people in Vicksburg following the fall of the city in July of 1863, the Church of the United Brethren sent Dickey and two other teachers to the former Confederate stronghold on a mission to “provide books and instruction for the mind” and “the gospel of Christ for the soul.” Dickey and her colleagues operated a school in Vicksburg for emancipated enslaved people for nineteen months. Although attendance was irregular during these months, more than three hundred students, mostly adults, flocked to the school, and a majority of them learned to read and write. The Church of the United Brethren also commissioned a church in Vicksburg, and in 1864, its chaplain performed more than three thousand official marriages for formerly enslaved people, whose prior, informal marriages were not legally recognized by the state. Dickey completed each certificate of marriage by hand for these couples.

When the Civil War formally ended in April of 1865, Dickey’s work in Vicksburg also came to a close. She learned much during her time in Mississippi. She also became intimately familiar with the challenges and frustrations of formerly enslaved people as well as their dedication, resiliency, and warm affection. Dickey became convinced that if she were to continue in what she now recognized as her life’s work – teaching African American women and children of life beyond servitude – she would need more preparation and training herself.

With few resources but great with determination, Dickey enrolled at Mount Holyoke, a female college in Massachusetts which was considered the best college in America at the time for training teachers. Within four years of her enrollment, Dickey mastered the curriculum as well as the college’s rigid structure of discipline and learning. She, however, gained much more than a piece of paper signifying her graduation in 1869. Through her affiliation with Mount Holyoke, Dickey gained a new family – the faculty and her classmates – who became her strongest supporters and defenders when she answered another mission call to return to Mississippi to teach. She first accepted a position with the American Missionary Association as a teacher in a school established in Raymond, Mississippi, by the Freedmen’s Bureau. However, when the Mississippi Legislature voted to fund public education in 1870 for both White and African American students, Dickey agreed to become the head of a new school established in nearby Clinton for African American children.

Dickey’s presence in Clinton was troublesome. Local White people would not rent to her because of the purpose of her employment. She was eventually able to rent a room from Charles Caldwell, a state senator and leader in the local African American community. Dickey was also shunned by White Clintonians when she attended the local Methodist church and was harassed by students of nearby Mississippi College when she walked the town streets.

Dickey taught at the Clinton school for a year before a lack of funding forced its closure. She was frustrated at first, but then learned of the pending sale of a property just outside the city limits where the antebellum Mount Hermon Seminary was located. Dickey came to believe that God wanted her to build a seminary for African American females in Clinton on the model of Mount Holyoke. She began raising funds and traveled to Ohio and Massachusetts where she won financial support from the United Brethren Church and her Mount Holyoke classmates. Senator Caldwell also persuaded his colleagues to donate to Dickey’s cause. Even local White people were attracted to her cause. For example, George Harper, the racist editor of the Hinds County Gazette, encouraged his readers to help Dickey. By 1875, she had enough money to buy the Mount Hermon Seminary property, which included one hundred and sixty acres of land, a large home, a barn, and other buildings.

Dickey’s new Mount Hermon Seminary for Colored Females would have opened in September of 1875, but a riot broke out at the beginning of that month causing a delay. The riot originated at a Republican political rally which had been organized by Senator Caldwell and other local Black leaders. The riot and the massacre that followed resulted in the deaths of between thirty and fifty African American men. Dickey was also present at the rally and was deeply troubled by the events she witnessed. She even wrote a letter to President Ulysses S. Grant pleading for his help and intervention. She pleaded, “Allow a humble woman to address your Excellence in behalf of the poor oppressed colored people of the Southern states and especially of this State. Seeing, as I do that thousands of them are just on the eve of being sacrificed at the hand of the assassin, I cannot hold my peace.” Three months later, Senator Caldwell was assassinated in Clinton because of his participation in the rally.

Dickey remained steadfast and determined to open the new school. She asked Walter Hillman, president of the White Central Female Institute in Clinton, to replace Caldwell as president of her biracial board of trustees, and Mount Hermon Seminary for Colored Females opened near the end of 1875. Based on the Mount Holyoke model, the students followed a regimen of rooming together, eating together, attending classes together, and sharing household duties of the school. Dickey and her sister taught classes, and Sarah also served as chaplain for the school. Her administrative duties required annual visits to her constituents in the North to raise money.

The females who attended Mount Hermon Seminary for Colored Females were boarding students in the beginning, but Dickey later allowed local girls to enroll as day students. Her church in Ohio paid for a school bell to signal the beginning of the school day for students who lived nearby. Dickey later purchased an additional one hundred and twenty acres of land from Walter Hillman and offered to sell the land in one acre plots to the fathers of her day students. She insisted that these men partner with her in the venture by paying a modest sum for the land. As lots were sold and houses built, the area became known as “Dickeyville” and still exists as a predominately African American community in Clinton today.

Dickey eventually earned and even commanded the respect and support of the White citizens of Clinton and nearby Jackson. She maintained good relations with the White political leadership when Reconstruction ended in 1876. When the postmaster of Clinton struck two of her students for not stepping off of a wood plank sidewalk as his wife approached them, Dickey talked to political leaders in Clinton and Jackson, and the man was removed from his position.

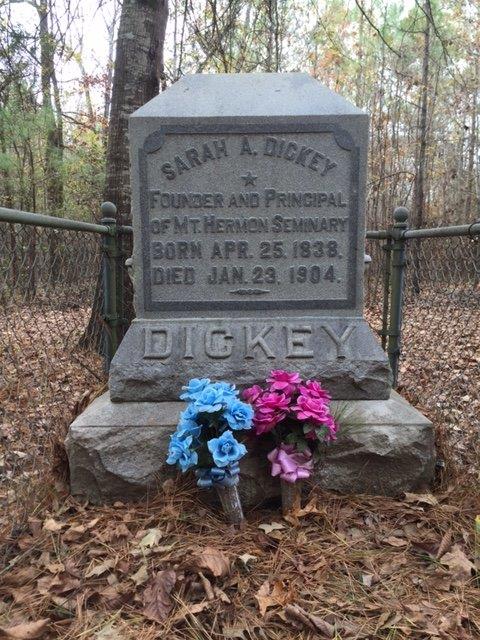

At the age of sixty-six, Sarah Dickey died on January 23, 1904, after a brief illness. Following her death, the Clarion Ledger, a Jackson newspaper, ran this headline: “Miss Sarah Dickey Dead; Principal of a Negro School near Clinton…She had labored under many difficulties but overcame them all.” Dickey was buried in a little cemetery on the seminary grounds where two of her students and the daughter of a third student were also buried. During her lifetime, several hundred girls enrolled at Mount Hermon Female Seminary for Colored Females and more than two hundred earned a certificate to teach.

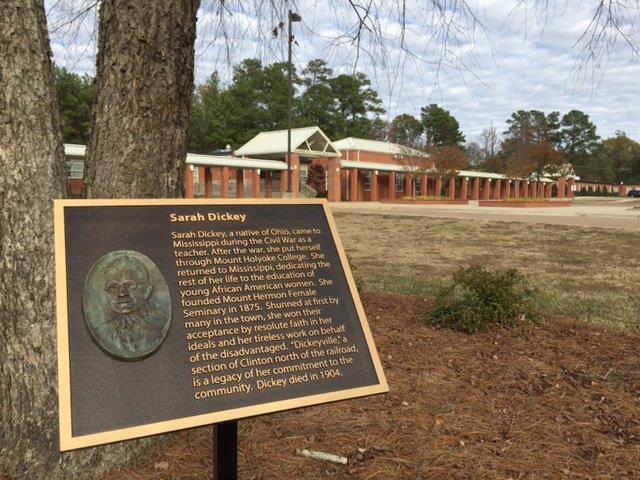

Following Dickey’s death, her niece and other individuals attempted to lead the school. However, the challenges Sarah Dickey overcame became too great for her successors. Mount Hermon Seminary for Colored Females closed in 1924. No one could replace her. The site, however, remains a place of education. In 1956, Sumner Hill High School was dedicated on the property and exists today as Sumner Hill Junior High School.

Sarah Dickey’s legacy to the people of Clinton is immeasurable. She helped to educate hundreds of teachers who took their training into the later segregated public schools of the city and the state by teaching the next generation of African American students. Her work can also be recognized by a proud African American community in Clinton known as ‘Dickeyville” and by a state historical marker dedicated by the City of Clinton to this remarkable woman of faith from Ohio.

Walter G. Howell, Ph.D. is a former mayor of Clinton and a retired professor of history who taught at Mississippi College for thirteen years. He currently serves as Clinton’s city historian.

Other Mississippi History NOW articles:

The Clinton Riot of 1875: From Riot to Massacre

Reconstruction in Mississippi, 1865-1876

Isaiah T. Montgomery, 1847-1924 (Part I)

Isaiah T. Montgomery, 1847-1924 (Part II)

Civil War: Vicksburg During the Civil War (1862-1863): A Campaign; A Siege

Lesson Plan

-

Portrait of young Sarah Dickey. Courtesy of the Clinton Visitor Center, Clinton, Mississippi. -

Photograph of Mount Herman Seminary Main Building and East Wing. Courtesy of The Clinton Visitor Center, Clinton, Mississippi.

-

Photograph of Sarah Dickey with the Mount Herman Female Seminary Class of 1897. Courtesy of The Clinton Visitor Center, Clinton, Mississippi. -

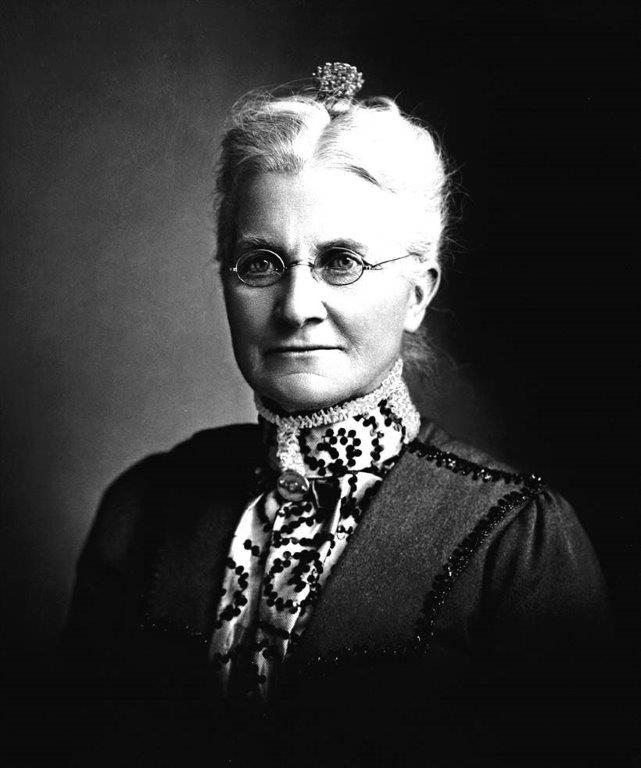

Portrait of Sarah Dickey circa 1900. Photograph from http://commons.wikimedia.org. -

Photograph of Sarah Dickey gravesite in Clinton, Mississippi. Courtesy of Melissa Janczewski Jones. -

Photograph of Sarah Dickey memorial erected by the City of Clinton in 2016 in front of Sumner Hill Junior High School. Courtesy of Melissa Janczewski Jones.

Sources and suggested readings:

Boutwell Report. 44th Cong., 1st Sess., Mississippi in 1875, Vols. I and II.

Griffith, Helen. Dauntless in Mississippi: The Life of Sarah A. Dickey 1838-1904. Washington, D.C.: Zenger Publishing Co. Inc.: 1965.

Howell, Walter. Town and Gown: The Saga of Clinton and Mississippi College. MI: McNaughton & Gunn, 2014.

Simon, John Y., ed., The Papers of Ulysses S. Grant. Vol. 26: 1875. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press, 2006.