In 1936, Time magazine suggested that “better than any living man, Senator Byron Patton Harrison of Mississippi represents in his spindle-legged, round-shouldered, freckle-faced person the modern history of the Democratic Party.” By then Harrison had been in politics since 1906 and now, thirty years later, he was chairman of the most powerful committee in the United States Senate. His political era had begun when the Democratic Party was in the doldrums, yet he had won national attention in the 1920s when Republicans held the presidency and control of Congress. When the Time writer singled him out, he was a Senate stalwart and chairman of the Committee on Finance.

Early years

Byron Patton Harrison was born in Crystal Springs, Mississippi, on August 29, 1881. His public school education was in Crystal Springs and after high school graduation as class valedictorian in 1899, he attended the summer term at the University of Mississippi. In the fall, however, he transferred to Louisiana State University on a baseball scholarship, but lack of funds caused him to drop out after two years. Harrison’s ability on the mound brought him an offer to pitch for the Pickens, Mississippi, semiprofessional team in the Old Tomato League, an opportunity he eagerly accepted. He then moved to Leakesville, Mississippi, where he taught school and became principal of the local high school. While teaching school in Leakesville he studied law in the evening and gained admission to the Mississippi bar in 1902.

Like many aspiring politicians, his first elected office was as a district attorney – in 1906 he was elected in the newly created Second Judicial District that caused his move to Gulfport. That Mississippi Gulf Coast town became his home base for the rest of his life. His 1910 campaign for a seat in the U.S. House of Representatives first introduced Mississippians to his brand of oratory, and they found it compelling and delightful. It made him a great favorite on the campaign trail. His longtime friend Clayton Rand, a Mississippi Gulf Coast editor, described Harrison’s style as spellbinding, “an eloquence that flowed like a babbling brook through a field of flowers.”

Gadfly of the Senate

Entering the House of Representatives in 1911 as its second youngest member, “Pat,” as he was now called, immediately made his mark as an effective debater against Republican tariff and tax policies. After the election of the Democratic President Woodrow Wilson in 1912, Harrison became a faithful adherent to Wilson’s proposed progressive legislation known as the New Freedom. Harrison presented such a remarkable contrast to Mississippi’s U. S. Senator James K. Vardaman both in style and in support of President Wilson’s preparedness program and the entry into World War I that Wilson personally endorsed Harrison when he ran to unseat Vardaman.

With the support of Wilson and his own increasing popularity with voters over his four terms as a congressman (1911-1919), Harrison defeated Vardaman in the 1918 U. S. Senate race and then was re-elected in 1924, 1930 (without opposition), and 1936. In the Republican-controlled Senate and with Republican presidents Warren Harding and Calvin Coolidge in office, Harrison was called the “gadfly of the Senate,” for his witty and stinging rebuke of Republican policies. In 1924 he gave a rousing keynote address at the Democratic presidential nominating convention at Madison Square Garden in which he focused upon the scandals of the Harding administration. (To read his speech, scroll to the bottom of the page at the University of Mississippi’s Hail to the Chief exhibition.) Historian Robert K. Murray wrote that Harrison “could talk on anything” and he “gave the convention a gourmet sampling of his forensic talents.” Pat Harrison is the only Mississippian ever to make a national convention keynote address.

I’m a good Democrat …

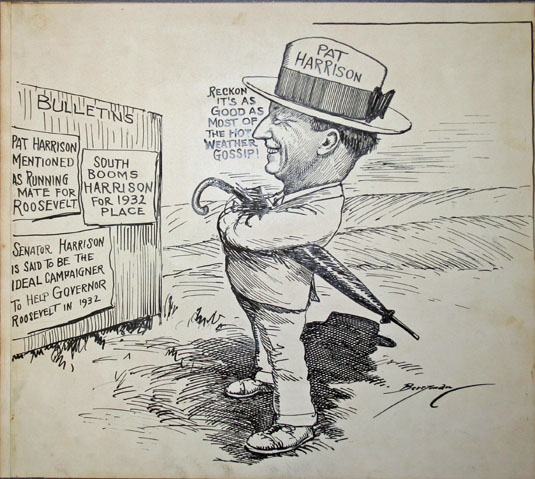

In 1932 Harrison was an early supporter of the anticipated nomination of New York Governor Franklin D. Roosevelt as the Democratic candidate for president. At the National Democratic Convention in Chicago he and his Senate colleague, Hubert D. Stephens of New Albany, held the Mississippi delegation for Roosevelt. With the ascendancy of a Democratic president and Congress in 1933, Harrison became the chairman of the Senate Committee on Finance, a position that placed him among the most powerful of Senate leaders. It was from this committee that the core of the economic legislation of the First New Deal (1933-1935) emerged for floor debate and passage: the Economy Act, repeal of prohibition, the National Industrial Recovery Act (all in 1933), and the Reciprocal Tariff Act of 1934. Both the repeal of prohibition and the NIRA turned on their tax features. Harrison was not in favor of the repeal of prohibition but he defended his work on the bill: “I am a good Democrat and I go through.”

After the cards of the First New Deal had been dealt, Mississippi had drawn at least $100,000,000 in needed funds. The entire Mississippi congressional delegation had supported Roosevelt’s requests. As Fred Sullens, the salty editor of the Jackson Daily News, roared, “We will stick with him until hell freezes over and then skate around with him on the ice.” Most Mississippians agreed.

Harrison concurred: “It is my duty to work in harness.” And he did as the Second New Deal (1935-1937) began with FDR’s request for a Social Security Act. Harrison was the prime mover of that measure as it went to the president for his signature in August 1935. He also went along with the Revenue Act of 1935 that included a “share-the-wealth” feature intended to placate the demand of angry millions who wanted a “soak the rich” tax scale. Harrison was not pleased with that bill because he believed that tax measures should be for revenue only and not for a redistribution of wealth. His loyalty to the president led him to ensure the bill was passed. It was then that political pundits began to see that Harrison was a “New Deal wheelhorse suspicious of his load.”

Events in 1937 were pivotal in the growing breach between Harrison and the president. In February, Roosevelt announced a plan for federal court reform that would permit him to name six additional Supreme Court justices. The “Big Four,” as the press called senators Harrison, James Byrnes of South Carolina, Joseph Robinson of Arkansas (Senate Majority Leader), and Vice President John Nance Garner, were increasingly wary of the centralizing tendencies of the administration. Their dissatisfaction with the “court-packing” plan was widely known, and the bill failed to pass.

After the death of Robinson in July, the general belief was that Senate Democrats would elect Harrison as majority leader, not Alben Barkley of Kentucky. Just before the vote, Roosevelt wrote a letter of support for Barkley. Harrison lost by one vote. Thus Harrison believed that the president was ungrateful for the “load” he had carried for the administration. The majority leadership would have been Harrison’s had his Mississippi colleague, Theodore G. Bilbo, voted for him. The enmity between the two went far beyond their dissimilarity – Harrison was no racist demagogue – to their rivalry for control of New Deal job patronage and the dispersing of federal money in their home state.

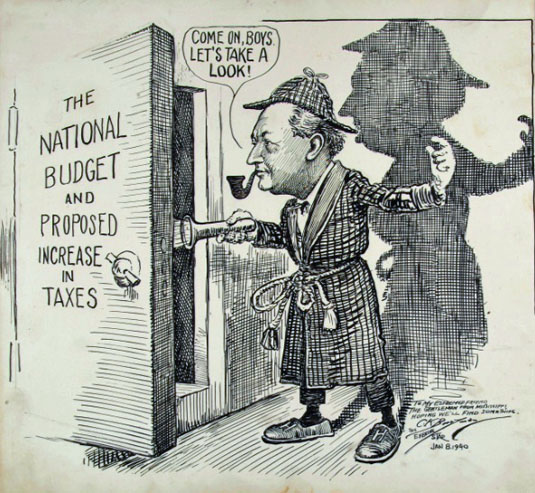

When other tax bills drafted by the president’s design reached the Finance Committee, Harrison managed to weaken them considerably. Harrison diluted the revenue bills of 1938 and 1939 that reflected the president’s continued insistence of taxes on capital gains and undistributed profits. Despite his loss to Barkley in 1937, by 1939 Harrison was at the zenith of his power. That year Washington newspapers voted him the “most influential” senator. Turner Catledge, the Mississippi-born managing editor of the New York Times, had described the Mississippian as the best “horse-trader” for his way of cajoling colleagues to pass his Finance Committee legislation. His influence, Catledge said, stemmed from the fact that Harrison never “welched” on a promise: “If Harrison told you something you could take it to the bank.”

Keen of intellect, sound in principle

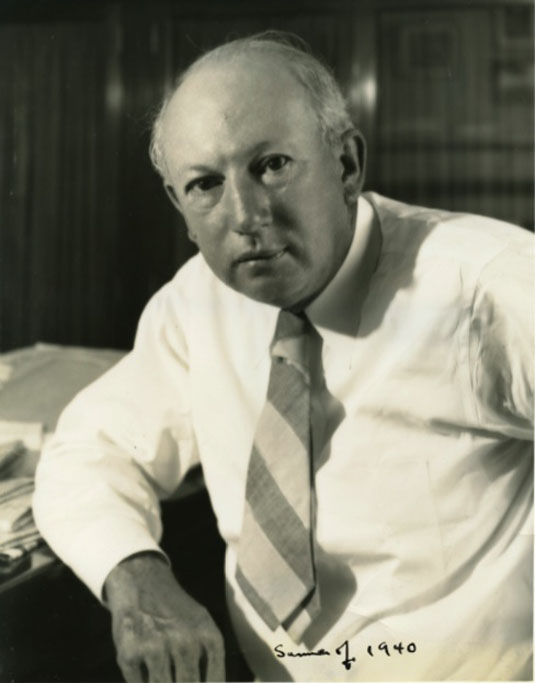

The Roosevelt-Harrison breach ended in 1940 when the threat of war made defense preparation the order of the day. Harrison supported Roosevelt’s bid for a third term in 1940: “We cannot afford to make a change of leaders.” In 1941 Harrison was elected president pro tempore of the Senate and when the president wanted a lend-lease measure passed to aid Britain and her allies, he asked that the bill go to the Finance Committee rather than to the Committee on Foreign Relations because he knew Harrison could “wrangle” it to passage. The bill became law in March 1941. By then Harrison was seriously ill with colon cancer and died on June 22, 1941. He was not quite sixty years old.

Accolades for the departed Senate giant were many and sincere. Roosevelt said of him that he had been “keen of intellect, sound in principle, shrewd in judgment [with] rare gifts of kindly wit, humor, and irony.” He was “square, approachable, and intensely human” said the editor of the Sunflower County, Mississippi, newspaper.

Pat Harrison has been largely forgotten in the years since his death. But it could be said that no Mississippi senator has since had such forensic talents and widespread popularity as Harrison that he would be invited to national podiums and would be sought after to campaign for Democratic colleagues across the country.

Martha H. Swain, Ph.D., is professor emerita at Texas Woman’s University and the author of Pat Harrison: The New Deal Years.

Lesson Plan

-

Pat Harrison at age 2. Courtesy Pat Harrison Collection, Archives & Special Collections, University of Mississippi. -

Senator Harrison gave a rousing keynote address at the 1924 Democratic National Convention at Madison Square Garden. Courtesy Pat Harrison Collection, Archives & Special Collections, University of Mississippi.

-

Berryman cartoon on speculation that Harrison would be selected as FDR's running mate in the 1932 presidential race. Courtesy C. K. Berryman Collection, Archives & Special Collections, University of Mississippi. -

Senator Harrison, right, in white suit, watches as President Franklin D. Roosevelt signs the Social Security Act. Harrison was the prime mover of the measure as it went to the president for his signature in August 1935. Courtesy Felton M. Johnston Collections, Archives & Special Collections, University of Mississippi. -

1938 Berryman cartoon shows Harrison directing the United States (Uncle Sam) to take the "decrease spending" road over "increase taxes" road. Courtesy C. K. Berryman Collection, Archives & Special Collections, University of Mississippi. -

Senator Harrison in 1940. Courtesy Pat Harrison Collection, Archives & Special Collections, University of Mississippi. -

Senator Harrison, as chairman of the Committee on Finance, gives a close look at the national budget in this 1940 Berryman cartoon. Courtesy C. K. Berryman Collection, Archives & Special Collections, University of Mississippi.

Bibliography

Catledge, Turner. Interview by Martha Swain, Special Collections, Mitchell Memorial Library, Mississippi State University.

Morgan, Chester. Redneck Liberal: Theodore G. Bilbo and the New Deal. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1985.

Murray, Robert K. The 103rd Ballot. New York: Harper & Row, 1976.

Pat Harrison Papers. University of Mississippi Special Collections

Patterson, James T. Congressional Conservatism and the New Deal. Lexington: University of Kentucky Press, 1967.

Swain, Martha H. Pat Harrison: The New Deal Years. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1978.

Swain, Martha H. “The Lion and the Fox: The Relationship of President Franklin D. Roosevelt and Senator Pat Harrison,” Journal of Mississippi History, November 1976.