It was late April 1865 and more than 2,000 tired, sick, and injured men, wearing dirty and tattered clothes, filed down the bluff from Vicksburg to a steamboat waiting at the docks on the Mississippi River.

The city of Vicksburg was ravaged by the American Civil War, and so were the men who were about to board the steamboat Sultana. Almost all were Union soldiers who had survived the battlefields only to be captured by Confederate troops and sent to prison camps in Alabama, Georgia, and Mississippi.

Most of the soldiers were young, including some who were only 14 years old. Boys could enlist, usually as musicians, with their parents’ permission, but some enlisted as soldiers by lying about their age. Many of the soldiers had already been injured in battle by the time they reached the prison camps, and their situation soon got much worse.

Prison camps

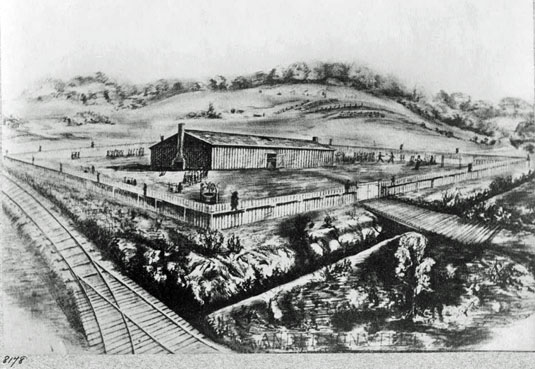

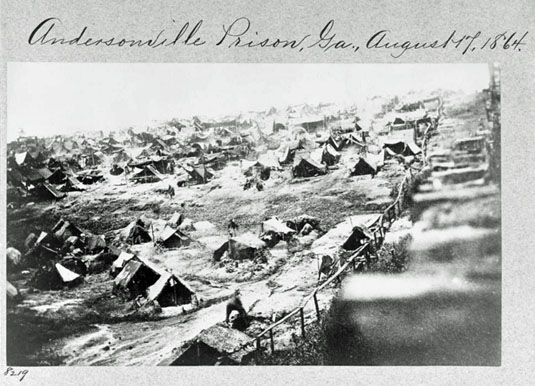

The Confederate prison camps were dirty, disease-ridden places and food and medicine were in short supply. This was true of prison camps on both sides, but life in the southern camps got considerably worse toward the end of the war when the Confederacy was having trouble feeding and caring for its own soldiers and citizens. Thousands of men died in the prison camps of starvation and disease. At the Alabama camp at Cahaba, the Alabama River jumped its banks and the flood forced the men to stand in waist-deep water for a week in winter.

By the spring of 1865, however, the war was close to its end, and the opposing armies agreed that it was time to release their prisoners and send them home. This was the best news the prisoners could hear. Soon they would be back home, close to their loved ones, with plenty to eat and a bed of their own to sleep in – everything they had dreamed of during their military service and captivity.

After the prisoners were released they had a hard time making their way west across the South to Vicksburg, where, they had been told, steamboats would carry them to their homes in the north. Traveling north from Vicksburg on the Mississippi River, boats could reach the Missouri, Ohio, and Tennessee rivers and, from there, the towns of the American Midwest from which the soldiers had come. But to get to the Mississippi River at Vicksburg the soldiers had to travel by boat, by train, and on foot. Because they were so weak from their war and prison experiences some of them died along the way. Making matters worse, some of the trains derailed due to the damaged railroad tracks — many of the railroad tracks had been destroyed by the war. In 1865 there were no highways and not even many good roads.

Rivers were then the best way to travel; they were like the interstate highways of the 21st century. After the recently freed prisoners reached Jackson, Mississippi, they had to walk the rest of the way to Vicksburg, which was then about 50 miles on the old road. Many of the men had no shoes and their feet were bleeding by the time they reached the Big Black River, just east of Vicksburg. They were also extremely hungry.

Camp Fisk

The Big Black River marked the dividing line between the part of Mississippi held by the Union army (which included Vicksburg) and the part held by the Confederate army (which included the area closer to Jackson). By then the fighting had ended, but only after they reached the area held by the Union army were the recently freed prisoners truly free. There, after crossing the Big Black River, they were given clean clothes and food at Camp Fisk, a neutral holding pen for prisoners of war. While arrangements were being made to transport them north on the Mississippi River they stayed in the camps outside Vicksburg, without tents or even blankets, and many got sick while waiting to board a steamer.

One reason for the boarding delay was that the owners of the steamboats were competing to see who could arrange for the most freed prisoners on their boats. The steamboat companies were paid as much as $10 per person to transport soldiers and freed prisoners, which was a lot of money in 1865, and some of the company employees bribed army officials in Vicksburg to make sure they got as many passengers as possible.

The steamship Sultana

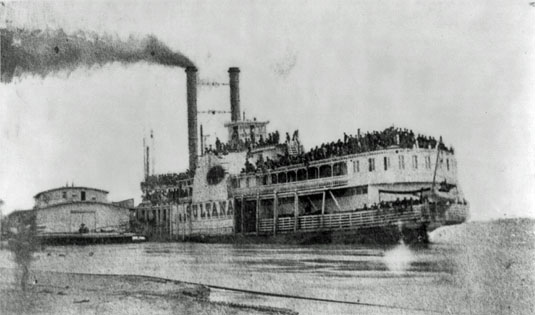

The Sultana was 260 feet long and 42 feet at its widest point and was designed to carry about 375 passengers and crew. It already had about 180 private passengers and crew on board, but by the time more than 2,000 paroled prisoners, their Union Army guards, a few Confederate soldiers headed home, and members of the U. S. Sanitary Commission boarded, the boat left Vicksburg with about 2,400 people on board – more than six times its capacity. There was standing room only. Many of the freed prisoners were so sick or badly injured that they had to be carried aboard. Still, the men were glad because they were on their way home.

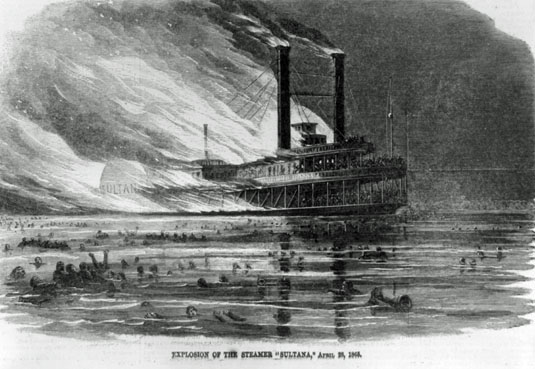

Unfortunately, the worst was still ahead. The overcrowded Sultana left Vicksburg traveling upriver to Memphis, Tennessee. Because the snow had melted in the north, the river was flooded and the boat struggled against the currents with its heavy load. In Memphis the boat docked and some of the men got off and toured the town. Late that night they re-boarded the boat and headed upriver again. Around 2 a.m., while most of the men were sleeping, the Sultana exploded and caught fire about seven miles upriver from Memphis. Some people later claimed the Sultana had been sabotaged by Confederate soldiers, but the United States government concluded that the boilers that heated water for its steam engines had exploded due to a faulty design and the heavy load of its human cargo.

Fires built in enclosed chambers heated water to the point that it turned to steam, and the pressure of the steam turned turbines that propelled water wheels, which in turn propelled the boat. A leak in the tubes that carried the super-heated water caused the explosion of the Sultana’s boilers, which destroyed the nearby parts of the boat and sent hot water and burning embers onto the sleeping passengers. Some were killed instantly by the explosion. Others awoke to find themselves flying through the air, and did not know what had happened. One minute they were sleeping and the next they found themselves struggling to swim in the very cold Mississippi River. Some passengers burned on the boat. The fortunate ones clung to debris in the river, or to horses and mules that had escaped the boat, hoping to make it to shore, which they could not see because it was dark and the flooded river was at that point almost five miles wide.

Of the approximately 2,400 people on board, about 1,700 died. The Sultana remains the worst maritime disaster in American history — more people died than with the 1912 sinking of the Titanic. There are reasons why the Sultana disaster is not well-known. The Civil War had just ended and President Abraham Lincoln had been assassinated, and the day before the Sultana disaster, Lincoln’s assassin, John Wilkes Booth, had been killed. Also, the American public had grown accustomed to hearing about loss of life on a large scale as a result of the battles of the war. A steamboat disaster was not enough to make big news. The Sultana disaster is rarely mentioned in history books.

Most of the passengers who survived did so by floating on pieces of the boat until they made it to shore or could be rescued. One man survived by floating almost 10 miles on the back of a dead mule. One survivor recalled that there was at least one person clinging to every tree along the flooded banks of the river. All of them were very cold, and some sang songs to try to keep their mind off their troubles. Other survivors mimicked the sounds of birds or frogs.

Word of the disaster reached Memphis when a passenger, a teenage boy, floated up to the waterfront and told the sentries what had happened. In the early morning hours of April 27, 1865, as word of the disaster spread, numerous boats began to assist in the rescue, and the survivors were sent to hospitals in Memphis. Many were naked by the time they were rescued, having shed their clothes to make it easier to swim. In Memphis they were given red long johns (much like thermal long underwear), which some of them wore as they wandered the streets of Memphis.

When they were well enough, the survivors were put on other boats and sent north, where they finally made it home. The Sultana remained at the bottom of the Mississippi River.

Alan Huffman is the author of Sultana: Surviving the Civil War, Prison and the Worst Maritime Disaster in American History. New York: Smithsonian Books, 2009.

Lesson Plan

-

Photographic reproduction of a drawing showing Civil War prison in Cahaba, Alabama. Courtesy Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, C-USZ62-113562. -

Andersonville Prison in Georgia, August 17, 1864. Courtesy Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Civil War Collection, LC-USZ62-122695.

-

The overloaded Sultana on the Mississippi River the day it headed upriver from Vicksburg. Union POWs jammed themselves aboard on the top, second, and bottom deck. Courtesy Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Civil War Collection, LC-USZ62-48778. -

Explosion on the Mississippi River of the steamer Sultana on April 27, 1865. Illustration in Harper's Weekly, May 20, 1865. Courtesy Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, LC-USZ62-77201. -

Sultana mural on the floodwall at Levee Street in Vicksburg, Mississippi. Artist, Robert Dafford. Courtesy Vicksburg Riverfront Murals.

Selected bibliography

Berry, Chester D., ed. Loss of the Sultana and Reminiscences of Survivors. 1892. Reprint, Knoxville, Tenn.: University of Tennessee Press, 2005.

Bryant, William O. Cahaba Prison and the Sultana Disaster. Tuscaloosa, Ala.: University of Alabama Press, 1990.

Elliott, James W. Transport to Disaster. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1962.

Foote, Shelby. The Civil War: A Narrative. New York: Random House, 1963.

Potter, Jerry O. The Sultana Tragedy: America’s Greatest Maritime Disaster. Gretna, La.: Pelican Publishing Co., 1992.

Salecker, Gene Eric. Disaster on the Mississippi: The Sultana Explosion, April 27, 1865. Annapolis, Md.: Naval Institute Press, 1996.

Speer, Lonnie R. Portals to Hell: Military Prisons of the Civil War. Mechanicsburg, Pa.: Stackpole Books, 1997. Reprint, Lincoln, Neb.: University of Nebreska Press, 2005.