In 2011 Mississippi newspapers reported that during the mid-20th century civil rights movement, more than one hundred Mississippi African Americans were victims of assault or murder, yet no perpetrators, many of them unknown, were identified or convicted. The injustices of that era evoke the history of another time described by the historian Vernon Wharton in his 1947 classic, The Negro in Mississippi, 1865-1890, during which more than one hundred and fifty victims suffered injustices. Most of those crimes received scant attention, if any, in the state’s newspapers, and an unknown number of crimes were not reported at all.

Wharton has a brief mention of the so-called Carroll County Courthouse Massacre that occurred March 17, 1886. It was a mass attack upon a group of African Americans in the courthouse room or on the courthouse grounds that left ten dead and another thirteen deaths resulting from wounds. The trouble began in January 1886 when two brothers, Ed and Charley Brown, half-Black and half-American Indian, were delivering molasses to a local saloon in Carrollton, the county seat. They bumped into and spilled molasses upon the clothing of Robert Moore, a White man said to be from Greenwood. An argument ensued and was quickly resolved, but the matter did not end there. A month later, Moore told his friend James Monroe Liddell, a Carrollton attorney and a Greenwood newspaper editor, about the incident. Liddell would deal with the Browns on behalf of his friend.

Courthouse killings

On February 12, 1886, Liddell confronted the Browns and accused them of deliberately spilling the molasses on Moore. A verbal dispute erupted between Liddell and the Browns, witnessed by several bystanders. When Liddell attempted to assault Ed Brown, onlookers intervened and prevented the argument from escalating to a full-scale fight. Unscathed, Liddell walked down the street to a hotel for dinner. Told by a friend that the Browns were making harsh, vulgar comments about him, Liddell left his meal to confront the brothers once again. This time gunfire erupted that left both Liddell and the Browns injured. There was no account of who fired first.

Many of Carroll County’s White citizens were shocked and incensed when the Browns soon charged James Liddell with attempted murder and intended to take him to court. Under the law they had a legal right to do so, but that a Black person would charge a White person with a crime infuriated Whites. The trial was set for March 17, 1886. A number of Black and White citizens were seated in place for a hearing of evidence when a group of armed men, said to number anywhere from fifty to one hundred, rode into town on horseback, dismounted at the courthouse, and ran into the courtroom through four doors. They fired a barrage of shots upon the plaintiffs and the Black citizens in attendance. Those who escaped from the second story windows were shot as they lay upon the ground or were hanging from a windowsill. No White person was hit. The renegades then rode out of town. Bullet holes on the courtroom walls were not covered until the courthouse renovation in the early 1990s.

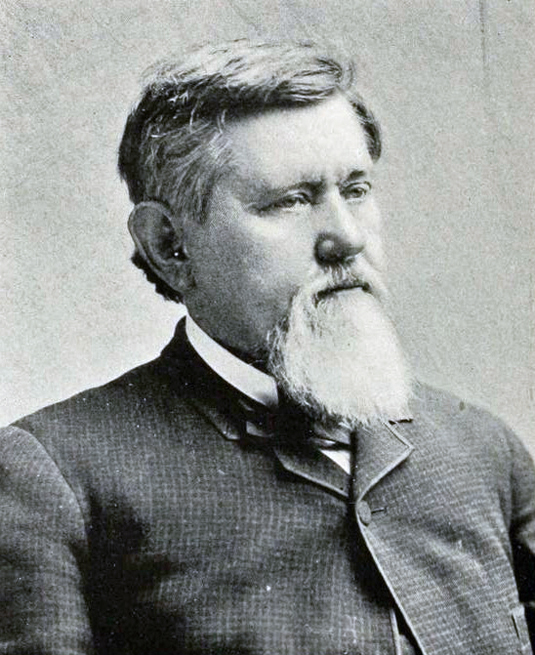

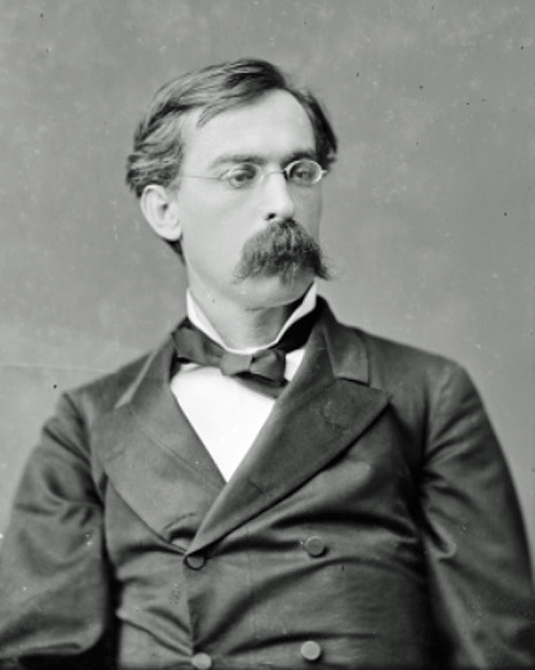

Within hours newspapers reported the attack. When New Orleans newspaper stories hit wires, people across the country and even abroad were outraged about this miscarriage of justice. Newspaper accounts and editorials in Boston, New York, Pittsburgh, Cleveland, Ohio, and Manitoba, Canada, called for an investigation of the killings. However, there was no apparent action taken by the county (no coroner’s inquest), the circuit court (no grand jury indictment), nor by Mississippi Governor Robert Lowry whose comment was, “The riot was provoked and perpetrated by the outrage and conduct of the Negroes.” In the United States Congress, Mississippi Senator James Z. George, who was from Carrollton, took no action. Four years later he would take a leave of absence from the U. S. Senate and become the chief architect of the Mississippi Constitution of 1890, noted for its stricture on Negro suffrage and its institution of Jim Crow segregation. George’s racial views reflected those of the most-often elected Carroll County politician at the time – Hernando DeSoto Money. Thus, nothing was forthcoming from Money to press for an investigation. He served in the U.S. House of Representatives (1881-1885) and was later elected to the U.S. Senate (1897-1911).

Killings condemned

Pleas for justice came when former senator Blanche K. Bruce, elected to the U.S. Senate by Mississippi’s Republican legislature during Reconstruction, and Mississippi ex-congressman John R. Lynch, both African Americans, visited President Grover Cleveland on March 24 to request action by the federal government. President Cleveland took no action. Congressmen and senators from Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, and North Carolina introduced bills and resolutions in Congress calling for an investigation of the massacre. North Carolina Congressman James E. O’Hara, an African American, made an impassioned speech and offered a resolution that an investigation be made in Mississippi by a committee of five congressmen, but it did not receive favorable action.

While Mississippi newspapers had heretofore written sparsely about African Americans murdered by White people, a few newspapers in Natchez, Vicksburg, Jackson, and Raymond for the first time condemned the killings at Carrollton. Historian Wharton wrote, “This seems to be the first time such a suggestion that perpetrators be identified and punished in the entire history of the period.” The editor of the Jackson Weekly Clarion wrote, “There can be no adequate punishment for the injury that has been afflicted upon the good people of Mississippi by the murderous mob at Carrollton.”

And then silence fell upon the Carroll County Courthouse Massacre. Witnesses could have identified any local men among the renegades, and perhaps even some from nearby Leflore County where hostilities toward African Americans ran high. No witnesses came forth, and none were identified to testify against Liddell. James Liddell became an elusive character and left Carrollton some time after 1886. He ended up in the Philippines and never returned to Carrollton.

A cold case

As time went by, Carroll County citizens dropped discussion of the event as the passing years took their toll of persons who had memory of the event. Thus, well into the 20th century Carrolltonians did not even know of the horror of March 17, 1886. There is no mention of the Carroll County Courthouse killings in any general history of the state. Carrollton’s famed author, Elizabeth Spencer, born in 1921, acknowledged that she had heard only the faintest sketches of the massacre. A wispy event Spencer described in her novel, The Voice at the Back Door, led Sally Greene, an English professor, to reconstruct events for a scholarly article in a literary journal. A local journalist, Susie James, resurrected the story in brief form for a Greenwood newspaper in 1996. However, neither of these publications shed any light on the event.

Perhaps an examination of the origins of the so-called Leflore County Massacre that occurred in 1889, only three years after the Carrollton killings, would shed light on the Carroll County Courthouse Massacre. Historian William F. Holmes wrote that at least twenty-five African Americans were hunted down and slaughtered in the Shell Mound area of Leflore County, a distance of no more than twenty-five miles from Carrollton. The basis for that massive search for Black farmers was the fear among some White people that an agricultural alliance formed by Black leaders would result in too many production and marketing advantages for Black farmers over White cotton growers. Just like the Carrollton massacre, neither local nor state officials took any action against the posse that carried out the murders. Those who were identified refused to talk, and African Americans were too terrified to speak, even to one another. Holmes concluded, “The troubles in Leflore County sprang largely from the attempts of blacks to improve themselves financially … . Whites used their power to keep blacks in economic and political subjugation.”

Regarding the Carroll County Courthouse Massacre, however, the central questions remain: Who plotted the attack? Who enlisted the force that stormed the courtroom? And, who were the individuals in the murderous mob? Altogether the Carroll County Courthouse Massacre of 1886 remains a cold case file.

Rick Ward, a retired naval officer with the NCIS, is a writer who has done extensive research into the Carroll County Courthouse Massacre. He resides in Brandon, Mississippi.

-

Carroll County Courthouse in Carrollton, Mississippi. Photograph by Rick Ward, 2009. -

Robert Lowry, governor of Mississippi at the time of the Carroll County Courthouse Massacre. Courtesy Mississippi Department of Archives and History; Call no. PI/1989.0008/27.

-

James Z. George, a Carrollton lawyer and U.S. senator from Mississippi (1881 to 1897). Photograph courtesy Library of Congress, Americana Collection. -

Hernando De Soto Money from Carroll County, Mississippi, was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives and later the U.S. Senate. Courtesy Collection of the U.S. Senate Historical Office.

Bibliography

Books

Kirwan, Albert D. Revolt of the Rednecks 1876-1925. New York: Harper Torchbook, 1965.

Wharton, Vernon, The Negro in Mississippi, 1865-1890. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1947.

Newspapers and journals

Carroll County Conservative, “Carrollton Pilgrimage a Great Success,” October 17, 2010.

Congressional Record, 49 Cong., n 1st Ses., HR Res. Doc. 203.

Greene, Sally. “Spencer’s Voice at the Back Door and the Legacy of Reconstruction.” Mississippi Quarterly Winter-Spring, 2005-2006.

Greenwood Commonwealth, “The Carrollton Massacre,” by Susie James, March 12, 1996.

Holmes, William F. “The Leflore County Massacre and the Demise of the Colored Farmers’ Alliance,” Phylon 34, 3rd Quarter, 1973.

New Orleans Times-Democrat, “A Frightful Tragedy,” March 18, 1886.

New York Times, “Ten Negroes Murdered,” March 18, 1886.

New York Times, “A Blight to Civilization,” March 26, 1886.

Winona Times, “Delving into History’s Dark Side,” September 30, 2010.

Manuscript

Ward, Rick, “The Hunt for James M. Liddell,” manuscripts in possession of author.