In May 1954, the United States Supreme Court announced in a unanimous decision that segregation—the practice of separating Black and White students, by law, within the public school system—was unconstitutional. That decision, Brown v. Board of Education, set into motion decades of organized, White opposition in southern states that had, since the 1890s, enforced laws to ensure that Black students and White students would not attend the same schools. The Citizens’ Council was the most recognizable organization committed to opposing the implementation of this court decision, and its presence in Mississippi ensured that desegregation would be difficult to enforce. Over the course of its existence, its work initiated the private school movement across the South and forged national and international networks of white supremacy that would deeply influence the political and cultural landscape of post-civil rights America.

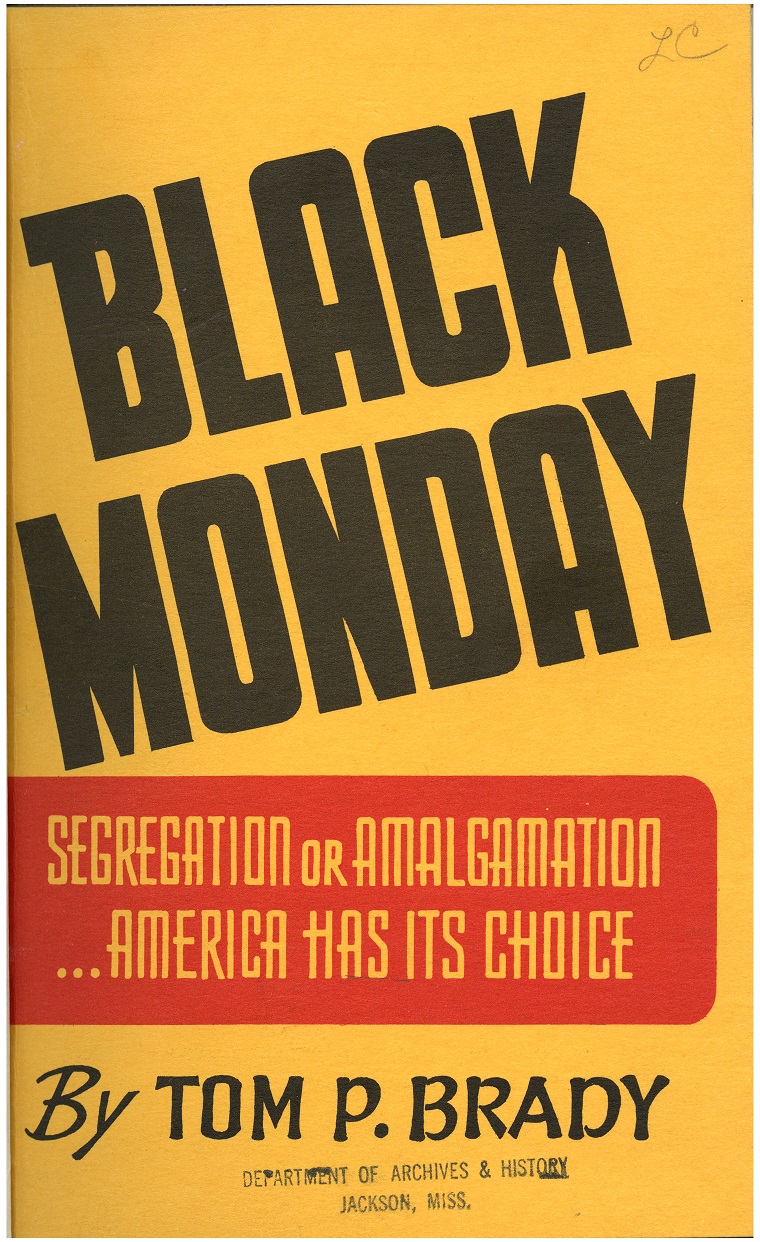

The first Citizens’ Council organized in July 1954, roughly two months after the Supreme Court announced the Brown decision. Robert “Tut” Patterson, a Delta planter who served as a paratrooper during World War II, feared the impact that desegregation would have in Delta communities where Black children vastly outnumbered White children. Inspired by Judge Tom Brady’s publication, Black Monday, Patterson called together business and civic leaders in his community to meet and design a plan that would preserve segregation in Mississippi’s public schools. After its initial meeting in Indianola, the Council movement spread into other Delta communities, where elected officials, members of law enforcement, and White business leaders worked together to detect and discourage local civil rights activity through the collective economic power that its members held, ensuring that White people were united in resisting desegregation. The organization’s founders embraced sophisticated White leadership as an effective alternative to more violent organizations, like the Ku Klux Klan, believing that civic and business leaders would keep violence at bay.

In the first few months that followed the Council’s founding in the summer of 1954, the chapters worked locally, collecting information on civil rights activists that would enable local business leaders to threaten them economically. Black teachers, farm workers, and loan recipients who were active in local chapters of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) were fired from their jobs or risked losing their loans if they refused to end their civil rights work. But by the fall, the Council became a visible force statewide. When Governor Hugh White announced his plan to preserve segregation with an equalization process, through which he promised to improve the quality of African American schools to better match that of White schools, Black leaders balked. Progress at the federal level to desegregate professional and graduate schools had been steady, and desegregation of public schools seemed imminent. White’s proposal to maintain separate—if better—facilities, was too little, too late. Black leaders responded to White’s plan with resistance, citing desegregation as the only acceptable plan going forward.

For many White Mississippians, the governor’s plan went too far. To them, especially those in predominantly white areas of the state, equalization signified less money for White schools and more money for African American schools. In the Delta, where White people were in the minority, the prospect of equalizing Black schools seemed untenable, given the vast disparities between the two systems. Because White planters in that area had more economic resources than other parts of the state, their response to Governor White’s proposal was to close the public school system altogether and set up private schools instead. With an aim to unify whites in the state behind opposition to desegregation, a constitutional amendment was proposed in the fall of 1954 that promised to close Mississippi’s public school system if the federal government forced implementation of the Brown decision.

Support for the school closure amendment was the first public campaign led by the Citizens’ Council. In October 1954, a statewide organization formed to assist with its passage. The Association of Citizens’ Councils of Mississippi (ACCM) operated out of Winona and enabled individual chapters across the state to collaborate within a central organization. More importantly, the ACCM initiated a robust publicity campaign that helped secure passage of the school closure amendment in December. Desegregation would not fully be implemented in Mississippi until 1969 and 1970, so public schools remained open and segregated. The Citizens’ Council’s leadership, however, was assured by the amendment’s passage and the organization’s rapidly increasing influence in the state. In the months that followed, the Council’s influence became more visible in the state legislature and crested with the election of Ross Barnett as governor in 1959.

As Council chapters increased across the state, Black activism plummeted. Medgar Evers, field secretary for the NAACP in Mississippi, wrote frequently to his contacts in other southern states about the organization’s intimidation tactics and the negative impact it was having on membership. Council chapters in other states throughout the South had similar results. Violence against Black activists who refused to buckle in the face of Council intimidation could be fatal. In 1955, Rev. George Lee, who worked hard to secure Black voter registration in Belzoni, Mississippi, was murdered. No one was ever charged for the murder. Reporters covering the Council’s work in Mississippi found multiple incidents in which the organization’s local pressure and surveillance discouraged Black activism and silenced local Whites who preferred more moderate approaches for preserving segregation.

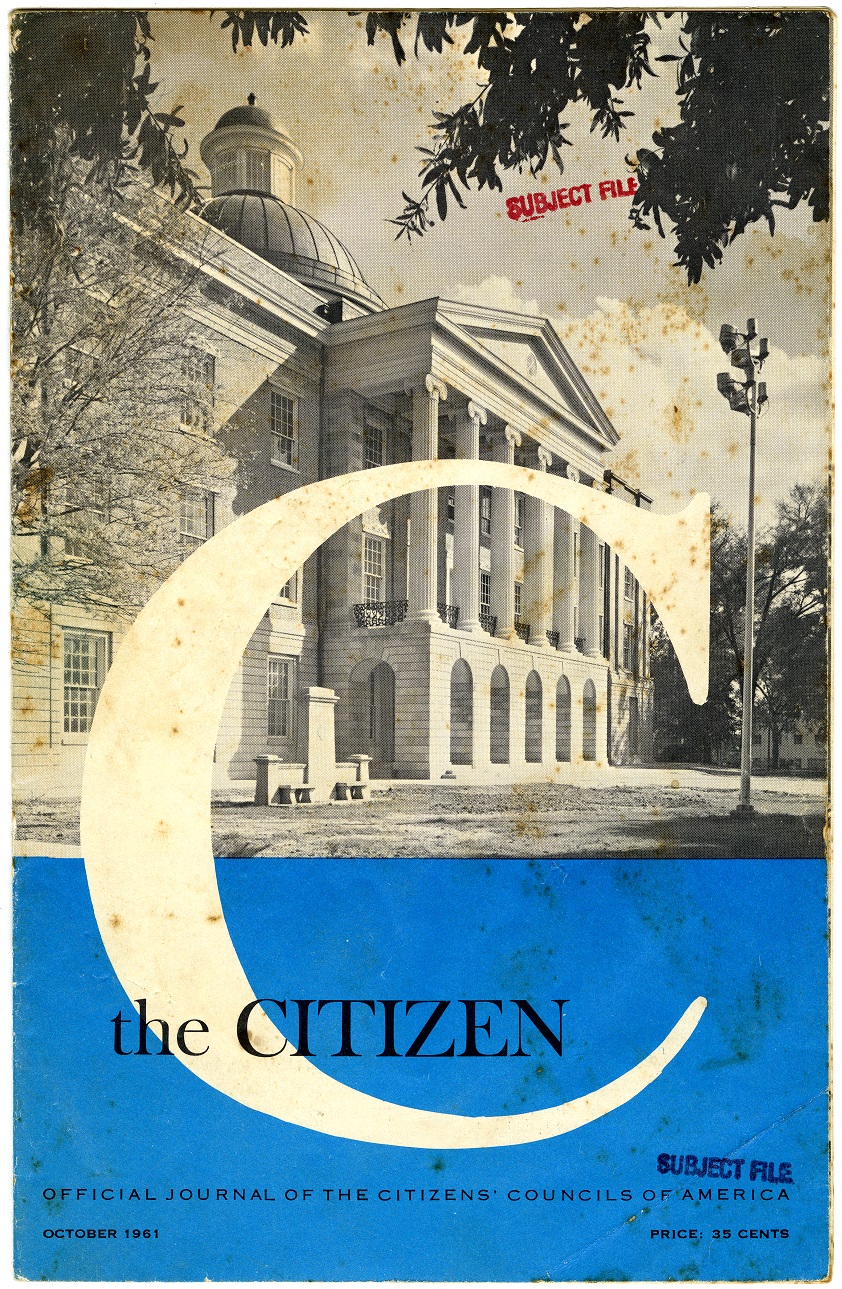

But the Citizens’ Council’s slogan, “States’ Rights, Racial Integrity,” went beyond securing segregation in Mississippi. In 1956, the Citizens’ Councils of America (CCA) formed. While its headquarters remained in Jackson until 1989, the CCA’s ambitions were national. Through its newsletter, The Citizen, and its weekly public affairs program Forum, the CCA connected the organization’s mission to preserve segregation to issues of national concern. Forum in particular provided the Council with a national platform by hosting congressmen and senators advocating for a variety of issues and political ambitions. The program, which ran from 1957 to 1966, recorded most of its programs in Washington, D.C., in congressional recording studios. With the support of Mississippi senator James O. Eastland and South Carolina senator Strom Thurmond, among others, Forum focused on the civil rights movement as only one example of federal overreach aimed at undermining state sovereignty. Through its engagement with northern and western elected officials, the Council’s identity as an exclusively southern organization diminished. With the civil rights movement in Mississippi stymied by a state government under the influence of Council leaders, the CCA directed efforts toward cultivating a language of conservative political principles that included a commitment to White supremacy.

In 1966, Forum recorded a series of programs on location in southern Africa, exemplifying its global aspirations. Intended as a defense of South Africa’s and Rhodesia’s (now Zimbabwe) White minority regimes, the southern Africa programs hosted government officials and White residents. Its most prominent guest was the rogue prime minister of Rhodesia, Ian Smith, who described Rhodesia’s oppressive approach to Black Rhodesians as a system akin to southern segregation, intended to honor biological racial differences that made people of color naturally inferior to White people.

The Council was also deeply involved in the presidential campaigns of Alabama governor George C. Wallace in 1968 and 1972. Wallace was an outspoken segregationist who won support throughout the country for his embrace of working class White people who perceived civil rights advances as obstacles for White success. Council administrator William J. Simmons, directed these efforts while supervising the publication of the Council’s newsletter, providing media exposure for Wallace, and advancing his message about Black crime as a natural outgrowth of civil rights successes.

After the desegregation of the University of Mississippi in 1962, an event that triggered violent White backlash that resulted in two deaths, the Council’s support in Mississippi waned. The passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 further undermined faith that the Council could prevent racial progress. As more radical groups like the Ku Klux Klan reemerged in the state, the Council’s focus turned to building support outside of the South. Citizens’ Council chapters began to appear in California in 1964, and the Council’s success there indicated a decided shift toward more radical forms of conservatism outside of the South that embraced “white majority” voting patterns as a countermeasure to growing Black political power.

Even as the Council’s focus expanded nationally and won support from radical organizations aligned with its belief in white supremacy, its most permanent impact was in Mississippi. In 1964, the Council opened its first private academy in Jackson, providing a model for private school education throughout the South. Recognizing its failure to maintain segregation in the public school system, the opening of private schools under Council leadership enabled Whites-only education to persist in a new form. The Council’s efforts were so successful in Mississippi, it hosted leadership conferences in other states that provided instructions on how to open a private school.

After over 30 years of active work, the Council ended publication of The Citizen. Its legacy for economic intimidation toward civil rights activists in the state remains well-known, but its contribution to a new form of segregation through private school support remains a visible component of Mississippi’s educational system. In 2019, Mississippi State University made Forum broadcasts available online through its Special Collections division, digitizing programs that highlight the variety of issues and guests the Council attracted.

Stephanie R. Rolph is an associate professor of history at Millsaps College. This article was adapted from her first book, Resisting Equality: The Citizens’ Council, 1954-1989, which was published in 2018 by Louisiana State University Press.

Lesson Plan

-

"The Citizen" was the newsletter of the Citizens’ Councils of America. -

In 2019, Mississippi State University made Forum broadcasts available online through its Special Collections division, digitizing programs that highlight the variety of issues and guests the Council attracted.

-

Black Monday was written to preserve White supremacy and referred to Monday, 17th May 1954—the date the Supreme Court announced its decision in Brown v Board of Education to integrate schools. -

Logo for the Citizens' Council Forum -

Ian Smith (left), prime minister of Rhodesia, and interviewed by William J. Simmons for "Forum."

Sources

Stephanie Rolph, Resisting Equality: The Citizens’ Council, 1954-1989, Louisiana State University Press, 2018.