The American Civil Rights Movement in the late 1950s and 1960s represents a pivotal event in world history. The positive changes it brought to voting and civil rights continue to be felt throughout the United States and much of the world. Although this struggle for Black equality was fought on hundreds of different “battlefields” throughout the United States, many observers at the time described the state of Mississippi as the most racist and violent.

Mississippi's lawmakers, law enforcement officers, public officials, and private citizens worked long and hard to maintain the segregated way of life that had dominated the state since the end of the Civil War in 1865. The method that ensured segregation persisted was the use and threat of violence against people who sought to end it.

Philosophy of nonviolence

In contrast, the leaders of the Civil Rights Movement chose the tactic of nonviolence as a tool to dismantle institutionalized racial segregation, discrimination, and inequality. Indeed, they followed Martin Luther King Jr.'s guiding principles of nonviolence and passive resistance. Civil rights leaders had long understood that segregationists would go to any length to maintain their power and control over African Americans. Consequently, they believed some changes might be made if enough people outside the South witnessed the violence African Americans had experienced for decades.

According to Bob Moses and other civil rights activists, they hoped and often prayed that television and newspaper reporters would show the world that the primary reason African Americans remained in such a subordinate position in the South was because of widespread violence directed against them. History shows there was no shortage of violence to attract the media.

History of violence

In 1955, Reverend George Lee, vice president of the Regional Council of Negro Leadership and NAACP worker, was shot in the face and killed for urging African Americans in the Mississippi Delta to vote. Although eyewitnesses saw a carload of White people drive by and shoot into Lee's automobile, the authorities failed to charge anyone. Governor Hugh White refused requests to send investigators to Belzoni, Mississippi, where the murder occurred.

In August 1955, Lamar Smith, sixty-three-year-old farmer and World War II veteran, was shot in cold blood on the crowded courthouse lawn in Brookhaven, Mississippi, for urging African Americans to vote. In Local People, John Dittmer writes “although the sheriff saw a white man leaving the scene 'with blood all over him' no one admitted to having witnessed the shooting” and “the killer went free.”

On September 25, 1961, farmer Herbert Lee was shot and killed in Liberty, Mississippi, by E.H. Hurst, a member of the Mississippi State Legislature. Hurst murdered Lee because of his participation in the voter registration campaign sweeping through southwest Mississippi. Authorities never charged him with the crime. According to Charles Payne in his book, I've Got the Light of Freedom, “black witnesses had been pressured by the sheriff and others to testify that Lee tried to hit Hurst with a tire tool. They testified as ordered. Hurst was acquitted by a coroner's jury, held in a room full of armed white men, the same day as the killing. Hurst never spent a night in jail.”

NAACP State Director Medgar Evers was gunned down in 1963 in his Jackson driveway by rifle-wielding White Citizens Council member Byron De La Beckwith from Greenwood, Mississippi.

Chaney, Goodman, and Schwerner

Perhaps the most notable episode of violence came in Freedom Summer of 1964, when civil rights activists James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner left their base in Meridian, Mississippi, to investigate one of a number of church burnings in the eastern part of the state. The Ku Klux Klan had burned Mount Zion Church because the minister had allowed it to be used as a meeting place for civil rights activists. After the three young men had gone into Neshoba County to investigate, they were subsequently stopped and arrested by Neshoba County Deputy Sheriff Cecil Price. After several hours, Price finally released them only to arrest them again shortly after 10 p.m. He then turned the civil rights workers over to his fellow Klansmen. The group took the activists to a remote area, beat them, and then shot them to death. Dittmer suggests that because Schwerner and Goodman were White the federal government responded by establishing an FBI office in Jackson and calling out the Mississippi National Guard and U. S. Navy to help search for the three men. Of course this was the response the Freedom Summer organizers had hoped for when they asked for White volunteers.

After several weeks of searching and recovering more than a dozen other bodies, the authorities finally found the civil rights workers buried under an earthen dam. Seven Klansmen, including Price, were arrested and tried for the brutal killings. A jury of sympathizers found them all not guilty. Some time later, the federal government charged the murderers with violating the civil rights of Goodman, Schwerner, and Chaney. This time the Klansmen were convicted and served sentences ranging from two to ten years.

In addition to these murders, violence persisted through mass arrests, jail beatings, lynchings, and church bombings. Eventually, national public exposure brought about substantive change. Once the cameras began to capture incidents similar to the ones described here, progress in the movement became a reality. President John F. Kennedy, and later President Lyndon Johnson, moved to put a halt to at least some of the violence by supporting the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

Arms in defense

Nonetheless, many African Americans had already taken it upon themselves to defend their lives and property with whatever weapons they could muster. Despite their adherence to the philosophy of nonviolence, Black Mississippians understood too well the implications of not being armed to defend their lives and property. Civil rights workers throughout the state set up around-the-clock surveillance of some of the churches and homes they used as meeting places. As far as they were concerned, not striking back while participating in a public protest was quite different from not defending one's home, church, or community center from imminent attack.

Griffin McLaurin, a Covington County activist, recalled his experiences for the University of Southern Mississippi's Center for Oral History. He said civil rights activists “were guarding all of our houses” and “we formed a little group that was patrolling the community and keeping an eye on our community center.” McLaurin noted that there was still plenty of fear because they received threats on their lives every day. He added that although individual citizens and racist groups like the Ku Klux Klan “blew up a lot of cars on the road going to the center,” they did not succeed in bombing it because they kept a 24-hour watch on the building. McLaurin stated that “they'd come in late at night and try to get to the center, but we had our guards. We stood our ground, and whenever we heard something that we thought wasn't right, we had our firepower.”

Walter Bruce, a Durant native and former chair of the Holmes County Freedom Democratic Party, told the Center for Oral History the story of how “fighting fire with fire” was the only way many African Americans and their supporters were able to survive the sixties.

Bruce:

"Well, our strategy was we always did carry our weapons out there. . . .And so, when they came over that Wednesday night and started to shooting, and when they got down there about half a mile, our people opened fire on them. And so, they turned around, and come back that a-way. And when they come back that a-way, the people on that side started shooting over they heads. And [when they] got in town, they said, "We not going to go back out there no more." And said “Them niggers got all kinds of machine guns out there.”...and that word got out, and so from then on we never had no more problems when we'd go out there [with] nobody coming by shooting no more. So that broke that up."

From these examples it is clear that many African Americans used the term and tactic of nonviolence quite loosely. Their public stance was undoubtedly necessary to attract supporters and to compel government action, while the more private reliance on armed self-defense was a reality that few activists shunned.

The larger Civil Rights Movement can attribute its success to the tactic of nonviolence contrasting with the exposure of violence-prone policemen, sheriffs, vigilante groups, and other defenders of the status quo. Yet, the tactic of armed self-defense was indispensable in order to protect lives and property since the courts and law enforcement officials often stood silent or protected the perpetrators of racist violence. Thus, African Americans and their supporters were compelled to fight the evils of segregation with nonviolence as well as with force. While this may seem paradoxical, it worked to advance their struggle for freedom, equality, and justice.

Curtis J. Austin, Ph.D., is professor of history at the University of Southern Mississippi.

-

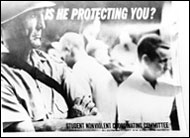

Poster, printed by the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, questions the role of the Mississippi State Highway Patrol in violence against blacks. Courtesy, McCain Library and Archives, University of Southern Mississippi. -

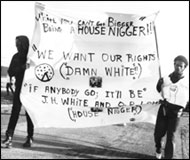

Civil rights protesters encourage a boycott in Grenada, Mississippi. Courtesy, McCain Library and Archives, University of Southern Mississippi.

-

Mississippi Valley State University students protest the decision by then-President James Herbert White to expel all students who were involved in protesting civil injustice and curriculum issues, specifically the lack of a Black Studies program. Courtesy, McCain Library and Archives, University of Southern Mississippi. -

Protest march for voting rights in McComb, Mississippi. Courtesy, McCain Library and Archives, University of Southern Mississippi.

Bibliography

Curtis J. Austin, Ordinary People Living Extraordinary Lives: The Civil Rights Movement in Mississippi, Hattiesburg, The Center for Oral History, University of Southern Mississippi, 2000.

Sally Belfrage, Freedom Summer, Charlottesville, University Press of Virginia, 1990.

Robert Burk, The Eisenhower Administration and Black Civil Rights, Knoxville, University of Tennessee Press, 1984.

Eric Burner, And Gently Shall He Lead Them: Robert Parris Moses and Civil Rights in Mississippi, New York and London, New York University Press, 1994.

Seth Cagin and Philip Gray, We Are Not Afraid: The Story of Goodman, Schwerner, and Chaney and the Civil Rights Campaign for Mississippi, New York, MacMillan, 1988.

John Dittmer, Local People: The Struggle for Civil Rights in Mississippi, Urbana, University of Illinois Press, 1995.

Myrlie Evers and William Peters, For Us the Living, New York, Doubleday, 1967.

Doug McAdam, Freedom Summer, New York: Oxford University Press, 1988.

Kay Mills, This Little Light of Mine: The Life of Fannie Lou Hamer, New York, Dutton, 1993.

Anne Moody, Coming of Age in Mississippi, New York, Dial, 1968.

Kenneth O'Reilly, Racial Matters: The FBI's Secret File on Black America, 1960-1972, New York, The Free Press, 1989.

Charles Payne, I've Got the Light of Freedom: The Organizing Tradition and the Mississippi Freedom Struggle, Berkeley, University of California Press, 1995.

Herbert Shapiro, White Violence and Black Response, Amherst, University of Massachusetts Press, 1988.

Timothy B. Tyson, Radio Free Dixie: Robert F. Williams and the Roots of Black Power, Chapel Hill, University of North Carolina Press, 1999.