Mississippi, like most of America, responded with unbridled patriotism when the attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941 thrust the nation into World War II. Thousands of Mississippians entered the armed forces. In every community, citizens on the home front contributed to the war effort. They raised money in war bond campaigns. They collected scrape metal, rubber, and other materials to turn in for recycling.

In addition, Mississippians and other Americans were limited in the use of scarce materials such as gasoline, tires, and certain food staples through federal control of the commodities. The controls were called rationing. People received rationing coupons which allowed them to purchase an allocated amount of restricted commodities.

War changes economy

The war years brought tremendous change to Mississippi, but the most significant change was to its economy — the war ended the Great Depression in the state. Agriculture, the most important sector of the prewar economy, went through significant and lasting change. Thousands of farm workers either entered the military or took other employment in 1940 and 1941. Yet in 1942, the War Manpower Commission, or WMC, rated the hills region, Mississippi Delta, and nearby Memphis, Tennessee, as areas with surplus farm labor. The WMC provided funds to help farm workers in these areas take temporary wartime jobs during the time between the planting and picking of crops.1

Plantation owners feared the WMC would create a labor shortage (or at least a shortage of low-wage workers.) They also worried about changes the wartime jobs might have on the social order. Most farm workers were African-American. Jobs off the plantation increased their independence. Plantation owners used their political influence and achieved the passage of a law that moved control of farm labor from the WMC to the United States Department of Agriculture, a governmental body they dominated at the state level. No longer would there be a federal agency to help workers obtain non-agricultural jobs. Furthermore, landowners controlled the local draft boards. Many farm laborers believed that deferment from the draft was available only to those who worked on the plantation owner's terms.2

The struggle between workers and owners continued throughout the war. Agricultural wages rose, as did owner's profits, but the wage increases were capped by Congress to combat wartime inflation. The dire labor shortage the plantation owners feared never materialized, but thousands of agricultural workers did leave for the military and higher paying industrial jobs. Rural farm population in Mississippi fell 19 percent in the 1940s while the urban population increased 38 percent.3

Immediately after the war, the use of heavy farm machinery increased dramatically. Wartime job opportunities, along with the mechanization of many agricultural tasks, brought a basic change in the character of the state's rural population.

Military suppliers

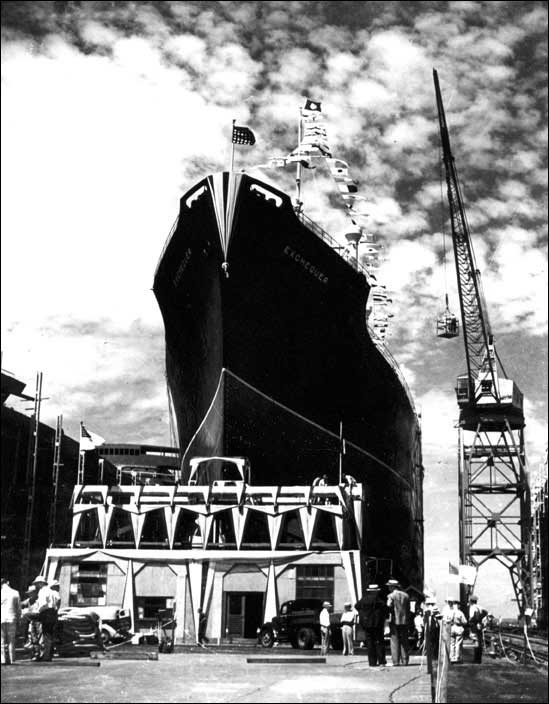

Mississippi had a small industrial base prior to the Second World War. The largest industrial employer during the World War II era was Ingalls Shipbuilding. Indeed, the war years were highly productive ones for the company. Ingalls established its Pascagoula shipyard December 6, 1938, under Governor Hugh White's Balance Agriculture with Industry program.

Its first contract was with the United States Maritime Commission for four cargo ships. But in August, 1941, during construction of the ships, the U. S. Navy requisitioned all four vessels for national defense. At the height of production, more than 12,000 men and women worked at Ingalls. In May, 1943, Ingalls completed the H.M.S. Battler, the first British combat ship built in the United States. By June 1945, Ingalls had constructed more than 70 ships.4

Mississippi's first ammunition plant was built in Flora at a cost of $15 million. An even larger ordnance plant was built in Prairie, near West Point. The $25 million project employed over 7,000 construction workers who built more than 300 buildings spread over 6,200 acres. Workers installed special telephones, water fountains, and other equipment needed to reduce the possibility of sparks and serious accidents.5

Other cities with large wartime industries included Jackson, Biloxi, Vicksburg, and Moss Point.

Small businesses suffer

On the national level, most wartime production took place in large factories. Thus, while industry as a whole increased dramatically during the war, smaller businesses sometimes suffered. It was difficult for small Mississippi industries to obtain wartime contracts. To make matters worse, small industries were often unable to continue normal production because of wartime shortages of raw materials.

Meridian native C.R. Webb experienced the problems of the wartime economy. He had a job as a traveling salesman, servicing small and medium-size lumber mills. Wartime use of lumber and other materials that were needed for the war effort severely limited Webb's sales, which were only a third of what they had been before the war. Wartime rationing of gasoline and tires affected his ability to travel. Webb was forced to give up his business for the duration of the war.6

The Merchants Company of Jackson, another small business, had to deal with wartime shortages. The wholesale company could no longer obtain tin to package coffee. They tried several containers, but the only one that could keep the coffee as fresh as tin was glass. Glass, however, weighed more than tin and the additional weight increased shipping costs. Glass could also break. In addition, grocery wholesalers and similar businesses had to factor in the increased costs that rationing caused.7

Some small businesses, of course, benefited from the upswing in the wartime economy. Harold Davis, owner of Radiolite Manufacturing in Jackson, won a contract to build wooden liners for ammunition boxes. He added a second shift and increased his work force from 10 to 30 employees. Ingalls Shipbuilding selected Green Brothers Lumber Company in Laurel to provide 1,300 prefabricated houses for Ingalls workers. Later, Green Brothers shipped more than 1,000 homes out-of-state.8

And in Hattiesburg, Komp Equipment used their existing factory to manufacture ammunition.9

Military camps

One of the largest boosts to the Mississippi economy in the war years was the establishment of military camps. Thirty-six installations dotted the map, with one million men and women from all over the United States coming into the state. The largest of these were Camp Shelby in Hattiesburg and Keesler Air Field at Biloxi. There were many others.

Camp Van Dorn, near Centreville, and Camp McCain, just outside Grenada, were major training camps. Air fields were located in Clarksdale, Columbus, Greenville, Greenwood, Grenada, Gulfport, Hattiesburg, Jackson, Laurel, Madison, Meridian, and Starkville.10 There were even four prisoner-of-war base camps in Mississippi.11

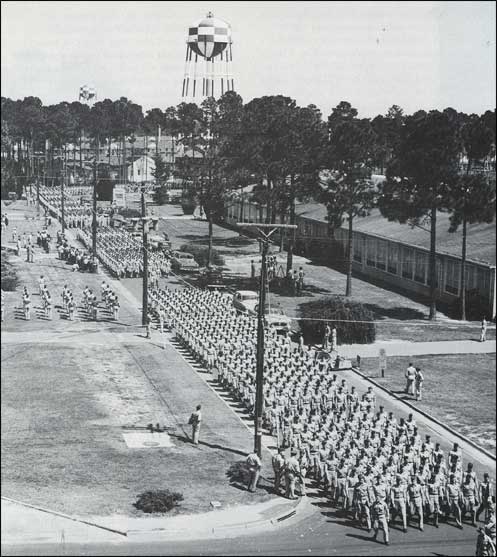

Camp Shelby, a World War I base deactivated in 1919, was designated a training camp when America began its defense buildup in 1940. In 1941, an $11 million construction project began at the base with a work force of over 12,000.12

When completed, Camp Shelby trained an estimated 50,000 troops at one time. There were as many as 30,000 additional military and non-military personnel who worked on the base as well.

Keesler Field in Biloxi was another huge base. Constructed in 1941, the air base cost $10 million and had 12,000 workers on the construction payroll.13

When Keesler hit its peak military population of 69,000, it was the largest air base in the world. Almost half a million mechanics and servicemen trained at Keesler.14

New factories and military training camps presented challenges for many Mississippi communities. A rapid influx of people meant that municipalities had to deal with increased demands on city infrastructures: roadways, water and sewer systems, police and fire departments, and schools.15

Nearly all cities that experienced a building boom encountered an accompanying housing shortage. The situation in Pascagoula, “a conglomeration of trailer parks, rusty boarding houses, old homes with charm but limited sanitary facilities,” was much like other fast-growing parts of the state.16

Areas in Mississippi with military installations also experienced an unfortunate effect of a new, large, and transitory population: an increase in vice. Hattiesburg leaders, for example, noticed dramatic increases in gambling, liquor, and prostitution violations after Camp Shelby was reopened.17

Social changes

Significant societal changes accompanied the economic changes. For the first time, women played a significant role in the state's industrial work force. At the Prairie ordnance plant, women were especially sought after to handle delicate materials.18

Komp Equipment reported that well over half, perhaps as much as 90 percent of its work force was female.19

Ingalls Shipbuilding had so many women workers that the federal government built a special room for workers with pregnancy difficulties.20

Social changes threatened to divide some communities. A large industrial work force on the Mississippi Gulf Coast led to the development of unions. While popular among laborers, unions were opposed by business leaders. When workers on the Gulf Coast struck over working conditions and pay in 1943, a local newspaper quoted a citizen as saying, “It is a pity that some of these labor union members ... couldn't inadvertently raise their head at the wrong time from a fox hole.”21

One of the most serious social problems that occurred during the war years was racial tension. Most of the military installations experienced some problems when African-Americans from outside the Deep South were confronted with racist Jim Crow rules that governed African-Americans in Mississippi.

None of the camps experienced a more serious situation than Camp Van Dorn when Black soldiers from the 364th Infantry Division were assigned there in 1943. Within hours after their arrival, citizens of nearby Centreville and members of the 364th had heated confrontations. A Black private was shot and killed in an altercation with military police and the local sheriff. Troubles continued throughout the summer of 1943. Once, angry members of the 364th broke into the arms room and threatened a riot. Calm was not restored at the camp until after the regiment was transferred to the Aleutian Islands.

However, there were rumors at the time, and they have nearly reached the level of urban legend, that hundreds of soldiers from the 364th were killed by Army officials after they crashed a white dance on the post. Yet even most of those who believe in an Army cover-up in the Van Dorn incident, think this is a gross exaggeration. Research into the incident continues.

End of agricultural dominance

The growth of Mississippi's economy during the war was very strong. Wages nearly tripled. Still Mississippi remained a poor state. It ranked last in the nation in per capita income before World War II and it ranked last at war's end. An inevitable decline in the economy occurred when defense plants and military bases closed after the war. But Mississippi's economy had permanently altered. The incredible dominance of agriculture over industry was over. In post-war years, the industrial, service, and professional sectors joined with agriculture to give Mississippi a more balanced economy.

Sean Farrell is assistant director, The Library of Hattiesburg, Petal, and Forrest County.

Lesson Plan

-

Ingalls Shipyard's first launch, and the world's first all-welded ship, was the Exchequer, 1940. Courtesy, Ingalls Shipbuilding, Pascagoula, Mississippi. -

Ingalls-built USS George Clymer, 1942. Courtesy, Ingalls Shipbuilding

-

War bond poster on Kennington's Department Store in Jackson, Mississippi. Courtesy, Mississippi Department of Archives and History -

Keesler Air Force Base in Biloxi, Mississippi, opened in June 1941 as a training center for pilots. Courtesy, Mississippi Department of Archives and History -

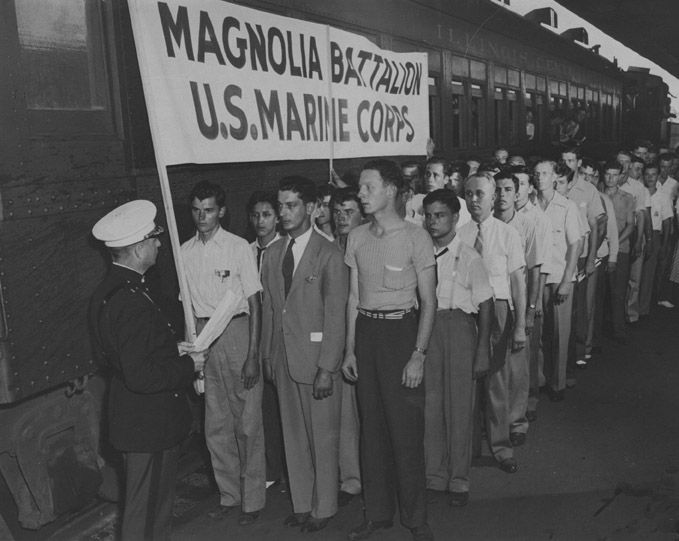

Young men board an Illinois Central train on their way for induction in the Marine Corp. Courtesy, Mississippi Department of Archives and History

Notes

1. Nan E. Woodruff, "Pick or Fight: The Farm Emergency Labor Problem in the Arkansas and Mississippi Deltas during World War II," Agricultural History 64:2 (1990), 77.

2. Ibid., 76-80.

3. Chester M. Morgan, “At the Crossroads: World War II, Delta Agriculture, and Modernization in Mississippi,” The Journal of Mississippi History 47:4 (1995), 361.

4. Robert F. Couch,“The Ingalls Story in Mississippi, 1938-1958,” The Journal of Mississippi History 26:3 (1964),192-200.

5. WPA Files, “World War II,” RG 60:137, Mississippi Department of Archives and History.

6. WPA Files, “World War II,” RG 60:135, Mississippi Department of Archives and History.

7. RG 60:137.

8. Ibid.

9. Kenneth McCarty and Christine Wilson, “World War II: Mississippi in Photographs," The Journal of Mississippi History 47:4 (1995), [320].

10. John Ray Skates, Jr., “World War II and Its Effects.” A History of Mississippi, Vol. 2. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi (1973), 122.

11. Terrance J. Winschel, “The Enemy's Keeper,” The Journal of Mississippi History 47:4 (1995), 326.

12. William T. Schmidt, "The Impact of Camp Shelby Mobilization on Hattiesburg, Mississippi, 1940-1946," Ph.D. dissertation, University of Southern Mississippi (1972), 10-11.

13. Verna Corriveau. “Keesler Air Force Base,” Mississippi Coast Magazine (June/July 1991) 28.

14. Skates, 122.

15. Sandra K. Behel, “The Mississippi Home Front During World War II: Tradition and Change" Ph.D. dissertation, Mississippi State University, (1989). Ann Arbor, Mich.: (1992), 30.

16. Ibid., 31.

17. Schmidt, 20.

18. RG 60:137.

19. McCarty and Wilson, [320].

20. Skates, 125.

21. Behel, 40.

Bibliography

Behel, Sandra K., “The Mississippi Home Front During World War II: Tradition and Change,” Ph.D. dissertation, Mississippi State University, 1989. Ann Arbor, Michigan, UMI, 1992.

Couch, Robert F., “The Ingalls Story in Mississippi, 1938 - 1958,” The Journal of Mississippi History 26:3 (1964): 192-206.

Corriveau, Verna, “Keesler Air Force Base,” Mississippi Coast Magazine (June/July 1991): 28-29.

“History of the 364th Infantry,” from Web site for Defense Technical Information Center. [2001, July 30].

McCarty, Kenneth and Wilson, Christine, “World War II: Mississippi in Photographs,” The Journal of Mississippi History 47:4 (1995): [315-322].

Morgan, Chester M., “At the Crossroads: World War II, Delta Agriculture, and Modernization in Mississippi,” The Journal of Mississippi History 47:4 (1995): 353-371.

Schmidt, William T., "The Impact of Camp Shelby Mobilization on Hattiesburg, Mississippi, 1940-1946," Ph.D. dissertation, University of Southern Mississippi, (1972).

Skates, John Ray, Jr., “World War II and Its Effects.” A History of MississippiVol.2. Jackson, University Press of Mississippi (1973): 120-139.

Winschel, Terrance J., “The Enemy's Keeper.” The Journal of Mississippi History 47:4 (1995): 323-333.

Woodruff, Nan E., “Pick or Fight: The Emergency Farm Labor Programs in the Arkansas and Mississippi Deltas during World War II,” Agricultural History 64:2 (1990): 74-80.

WPA Files, “World War II,” RG 60:135, Mississippi Department of Archives and History, Jackson.

WPA Files, “World War II,” RG 60:137, Mississippi Department of Archives and History, Jackson.