Definitions for Equal Rights Amendment

- Equality of rights under the law shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex.

- The Congress shall have the power to enforce, by appropriate legislation, the provisions of this article

- This amendment shall take effect two years after the date of ratification.

—full text, the Equal Rights Amendment

A primary goal of the modern women’s rights movement which began in the late 1960’s was the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA). This amendment was first proposed in 1923, just three years after American women gained the right to vote through the Nineteenth Amendment. Its earliest proponents, members of the National Woman’s Party, were aware that receiving the vote did not end all the lingering injustices faced by the women of the nation. These women, and ERA supporters in the 1960s and 1970s, believed that adding the ERA to the United States Constitution would make any laws denying equality to women unconstitutional and thus sweep away all of the old laws that they considered unfair to women.

One of the most important victories in the history of the modern women’s rights movement came in 1972 when Congress approved the ERA by overwhelming majorities. The House approved it in October 1971 by 354 to 23, and in March 1972 the Senate approved it by 84 to 8. When the ERA was submitted to the states for ratification, there was a mad scramble to ratify — fourteen states ratified within a week. Within three months, twenty states had ratified. By the end of 1972, thirty states had approved it — and only eight more were needed for ratification.

The ERA was not ratified, however, as it never met the requirement established by framers of the Constitution that amendments must be approved by three fourths of the states. In 1978 Congress extended the original 1979 ERA deadline to 1982, but when the new deadline came and went, the ERA remained three states short of ratification. Mississippi did not ratify the ERA. In fact, the Mississippi Legislature was the only state legislature which never voted on the amendment.

That the ERA had such widespread support in the 1970s seems somewhat surprising today, given that the amendment proved to be unsuccessful. Unlike the amendment granting woman suffrage which was slow to be approved by Congress but was ratified in 1920 a little more than a year after being submitted to the states, the ERA enjoyed overwhelming support in 1972 — only to begin almost immediately a long slide to eventual failure.

STOP ERA

The growing activism against the ERA owed much to Phyllis Schlafly of Illinois, who founded STOP ERA (Stop Taking Our Privileges) in October 1972. Schlafly enjoyed particular success in the South, where large numbers of southern conservatives including evangelical Protestants regarded the modern feminist movement as an assault on the traditional role of women which many regarded as divinely ordained.

Schlafly was strongly supported by conservative women in Mississippi who fought ERA partly in order to preserve the government’s right to make separate and different laws for women and men. They did not believe in the “equality” of the sexes if this meant “sameness,” and many upheld the idea of male dominance, especially of the household. During the battle over the ERA in Mississippi, Ellen Campbell, a state leader of STOP ERA, declared: “Man is the head of the home. In the societal order of things, he is above the women.” They believed that, if the ERA was ratified, women would lose many privileges including being supported by husbands and being exempt from military service.

In addition, conservative women in the state shared Schlafly’s distrust of the federal government and were very concerned that, given the vague language of the ERA, enforcement would be left to judges who would decide how laws must be changed to comply with the amendment.

Peggy Rayborn of Hattiesburg, an officer in Women for Constitutional Government, said that the wording of the ERA was “so simple it is open to just any kind of interpretation by the courts” and pointed out that “the Civil Rights Act is an excellent example of what can happen.” “The main result of the passage of the ERA would be to transfer jurisdiction of all laws pertaining to women and the family from the states to the federal government and courts. Considering the mess they make of everything, this would be catastrophic. Besides, the government has enough power and interferes too much as it is.”

ERA advocates

On the other hand, most modern women’s rights advocates, including ERA advocates in Mississippi, believed that most differences in the sexes, particularly in aptitudes and attitudes, were the result of “nurture more than nature” — in other words, the result of societal influences rather than inborn traits. They believed that the government should not be encouraging the continuance of traditional divisions in the roles of men and women by making separate laws for the two sexes. They argued that women should be free to choose whatever careers they preferred as individuals and that decisions regarding family life, such as which parent took on primary responsibility for taking care of children, should be decided by the family and not by the government.

ERA advocates also insisted that existing laws did not give women equality under the law, particularly regarding access to credit, and that discrimination against women in education and employment meant that most women earned far less than most men. They advocated federally supported child care, arguing that many families, especially single-parent families, needed that assistance.

In addition, many ERA advocates believed that women should take on equal obligations with men in defending their country, though some pointed out that compulsory military service — the draft — had been abolished.

In October 1972, ERA supporters met in Jackson and formed a coalition to prepare for a ratification campaign. The coalition included: the American Association of University Women (AAUW), the League of Women Voters (LWV), the Mississippi Nurses Association, the Jackson Women’s Coalition, the AFL-CIO, National Organization for Women (NOW), and the Mississippi Hairdressers and Cosmetologists. Jean Muirhead, a Jackson attorney, and former state senator, spoke on the legal status of women, and Dr. Connie McCaa, coordinator of the task force on ratification of the ERA for the Jackson chapter of NOW, discussed the need for the ERA to improve the economic status of women. House of Representatives member John Eaves of Hinds County announced his intention of sponsoring the amendment.

ERA in the legislature

As the Mississippi Legislature opened in January 1973, the Equal Rights Amendment was introduced in both chambers. The Senate Constitution Committee allowed ERA advocates to speak as well as four ERA opponents from Louisiana who “warn[ed] Mississippi of the dangers” of the ERA. Representative Betty Jane Long of Meridian was appointed head of a subcommittee of the House to study the ERA. She also held hearings on the amendment. But the amendment did not receive the number of votes necessary to be approved by the committee and reach the full legislature for a vote.

In 1974 Representative Long’s subcommittee heard more testimony before a packed house of over 200 people — closely divided between supporters and opponents — but again the amendment died in committee. Indeed, in the ten-year period in which the ERA was introduced in the legislature, it never got out of committee — the only state where this was the case. By 1974, Bobbye Henley, AAUW leader and Mississippi ERA Ratification Committee head, acknowledged that the ERA’s chances in the state were “very, very slim.” For the remaining years before the deadline, getting the amendment out of committee seemed to be the best the supporters could hope for.

Unlike 1920, when an all-male legislature debated the woman suffrage amendment, the Mississippi Legislature that considered the ERA had women members who played an important role in shaping its response. For several years there was even a woman occupying the illustrious post of lieutenant governor — Evelyn Gandy of Hattiesburg. But women legislators remained few in number and many opposed ratification and seemed to believe that their constituents expected it of them.

Representative Betty Jane Long and Senator Berta Lee White of Bailey were the objects of considerable criticism from feminists for their opposition to the ERA. But Long declared that they would be doing women no favors by approving the ERA: “If it didn’t do anything else than draft women into combat service, it would be real hard to explain to women that you were doing a service for them.” She also regarded the ERA as unnecessary, and of little interest to other legislators.

Senator White insisted that women in manufacturing still needed protective legislation, and that there were no possible gains from ERA worth the risk of women being drafted. If it were only about equal pay for equal work, she said “I’d be leading the march.”

ERA proponent Jo Hollman of NOW and the YWCA said that as long as the women members were against the ERA, that was a major factor to overcome.

As the most prominent woman politician in the state, Lieutenant Governor Evelyn Gandy was constantly asked about the ERA, and was very cautious: in 1976 she was quoted by The Clarion-Ledger as saying: “I personally favor it. But I don’t believe it is a priority item for Mississippi women. There are other matters of more importance . . . such as education and health care.”

In the 1970s and the early 1980s, however, the ERA was a political land mine not only for Gandy but for politicians male or female who, in the state’s conservative political climate, had good reason to tread carefully. In 1979, The Clarion-Ledger attacked Gandy for “socialism” for supporting ERA. William Winter, lieutenant governor from 1972 to 1976, and governor from 1980 to 1984, was an open supporter, but recalled later that he was unable to get any of the committees to send the amendment to the floor. Like Gandy he was denounced by ERA opponents and also criticized by supporters who claimed he did not try hard enough.

IWY

There seemed to be no organized opposition — or any need for it — until 1977. In that year, Mississippi, along with all the states, held an International Women’s Year (IWY) Conference sponsored by Congress. The conferences were viewed as extremely important by feminists and antifeminists alike, as Congress was asking the women of the nation for recommendations on what the federal government should do to make American society a more just society for women. At each state conference, participants were to adopt a set of resolutions and elect delegates who would represent their state at a national IWY conference to be held in Houston, Texas, in November 1977.

At the Mississippi IWY Conference, held in July 1977 in Jackson, the state’s feminists and antifeminists came together in a clash of cultures. The group of women’s rights veterans, pro-ERA, who had been appointed by the U.S. State Department to organize the conference, publicized it widely. But they were surprised when the conservatives arrived in numbers that allowed them to dominate the conference and adopt a strongly anti-ERA, antifeminist set of resolutions and a complete slate of conservative delegates to send to the national IWY conference.

The conservative coalition, calling itself “Mississippians for God, Country, and Family,” included many religious conservatives, encouraged by their churches to attend and defend traditional ideas about women’s role.

The conservative participants also included a number of Mississippians well known for their opposition to the Civil Rights Movement. Dallas Higgins, the wife of a prominent Ku Klux Klan leader, was among the delegates elected to represent Mississippi at the national conference. In contrast, the feminists at the conference included African-American women well known for their advocacy of civil rights as well as women’s rights in Mississippi. One of them, Jesse Moseley, was elected earlier by the feminist organizers to chair the state IWY Commission and the conference.

The conference made it clear how sharply polarized Mississippians were on the ERA and women’s rights issues. Feminists felt demonized by the conservatives who were indeed harsh in their portraits of ERA-supporters, denouncing them as communists who were anti-God and anti-family. Since many of the ERA supporters were married with children and active in their churches, they were amazed. AAUW leader Cora Norman recalled later that she and many of the feminists were “flabbergasted” at the accusations made against them as a group.

The conference also seemed to unify and motivate both feminists and conservatives and to inspire each side to greater activism. It also made Mississippians, including the press and the politicians, even more aware of the strength and numbers of conservative women in the state which meant that the IWY conference probably did more harm than good for the ERA’s prospects in the state.

Deadline extended

When in 1979 Congress extended the deadline for ratification by three more years, Mississippi politicians were not pleased. Senator John Stennis helped sponsor an amendment to it saying that Congress could not extend the deadline without allowing states to rescind their ratification. Both he and Mississippi’s other senator, James Eastland, voted against the extension. But even some pro-ERA politicians in the state, including William Winter, were critical of extension.

As the final year approached, Mississippi feminists continued to show the colors and to campaign annually for passage of the amendment. In July 1981, NOW members in Hattiesburg staged a “countdown rally,” one of 180 such rallies around the nation, and a “walk-a-thon” to raise money for the final push for ratification. The money they raised, however, was by their own choice designated for ratification campaigns in other states, as Mississippi and national NOW leaders considered it a waste to spend much on Mississippi.

On June 30, 1982, the deadline for the ERA expired. Ironically, as noted by journalist Bill Minor in a column for The Clarion-Ledger, “the day after the Great Threat (The Equal Rights Amendment, of course) was over,” Governor Winter appointed the first woman to the State Supreme Court in the 175 year history of the state — Judge Lenore Prather. The same day, the U.S. Supreme Court declared that Mississippi could no longer run a state-supported institution of higher learning that was open to women only (Mississippi University for Women). Though the Mississippi legislature had taken no action on the ERA, opportunities were opening up to women and laws that treated men and women differently were being challenged and often overturned.

In Mississippi, as elsewhere in the nation, ERA supporters continued their efforts. State supporters of the ERA immediately introduced a state equal rights amendment, believing that they might have a better chance now that this was solely a state issue. As Bobbye Henley put it, “I told myself that this time we don’t have to argue about federal intervention and we don’t have to talk about the draft.” But again conservatives, including ERA opponent Dot Ward, argued against it on the grounds that women had all rights they need. Said Ward, “We have had ten years and three months of ERA and I say it’s time to put it to rest.” The state equal rights amendment — like the ERA — died in committee.

On March 22, 1984, the Mississippi Legislature, without fanfare and with no opposition, ratified the Nineteenth Amendment — something that thirty-six other states had done half a century earlier. Mississippi’s ratification had no actual effect since Mississippi women had been given the right to vote through the action of other states back in 1920. Some interpreted this as a gesture to show that legislators were not hostile to women’s rights in the wake of the ERA defeat.

This belated approval mattered little to feminists in Mississippi and throughout the nation, however. In their eyes, a poor showing on the suffrage amendment and the fact that Mississippi lawmakers blocked the ERA before it ever came to a vote, gave Mississippi one of the worst records on women’s rights in the nation. By 1982 it was clear that women in the state and the nation were very divided in what they thought was best for American women. And though the ERA seemed dead — at least for the foreseeable future — the issues that surfaced during the battle over ratification would be debated in Mississippi and the nation for years to come.

Marjorie Julian Spruill, Ph.D., is associate vice chancellor for institutional planning and research professor of history at Vanderbilt University. Previously she was professor of history at the University of Southern Mississippi. She is the author of New Women of the New South: The Leaders of the Woman Suffrage Movement in the Southern States, Oxford University Press, 1993. In addition, she has edited several books on women’s history and co-edited a United States history textbook with a focus on the South, The South in the History of a Nation: A Reader.

Jesse Spruill Wheeler, her son and a junior at Hattiesburg High School, studied Mississippi history while in the ninth grade during the 2000-2001 school year.

-

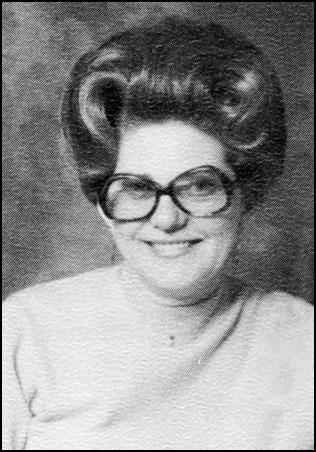

The ERA was a political land mine for Evelyn Gandy, lieutenant governor of Mississippi 1976-1980. Courtesy, Mississippi Department of Archives and History. -

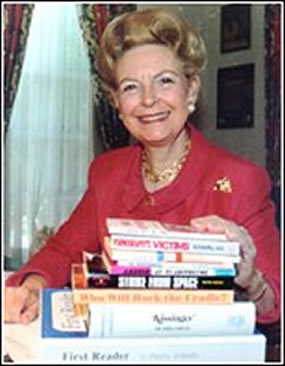

Phyllis Schlafly, who founded STOP ERA, enjoyed particular success in the South. Courtesy, Phyllis Schlafly.

-

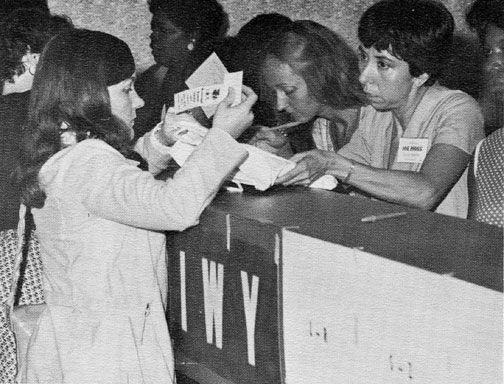

Women register for the Mississippi IWY Conference in Jackson. The state’s feminists and antifeminists came together at the July 1977 conference. Courtesy, Mississippi Department of Archives and History. -

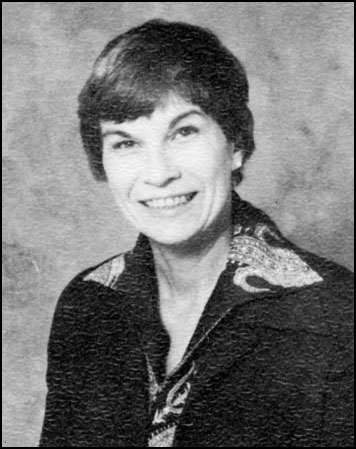

Jean Muirhead, a Jackson attorney and former state senator, spoke on the legal status of women at the October 1972 meeting of ERA supporters to form a coalition for a ratification campaign. Courtesy, Mississippi Department of Archives and History. -

Cora Norman, AAUW leader and ERA supporter, recalled that ERA supporters were “flabbergasted” at the accusations made against them as a group by the conservative coalition. Courtesy, Mississippi Department of Archives and History.

Suggestions for further reading:

Boles, Janet K. The Politics of the Equal Rights Amendment: Conflict and the Decision Process. New York: Longman Press, 1979.

DeHart, Jane Sherron and Donald G. Matthews. Sex, Gender, and the Politics of ERA: A State and the Nation. New York: Oxford University Press, 1990.

Felsenthal, Carol. The Sweetheart of the Silent Majority: The Biography of Phyllis Schlafly. Garden City, New York: Doubleday & Company, Inc., 1981.

Hartmann, Susan. From Margin to Mainstream: American Women and Politics Since 1960. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., 1989.

Mansbridge, Jane J. Why We Lost the ERA. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1986.

Schafly, Phyllis. The Power of the Positive Woman, 1977

Thomson, Rosemary. The Price of LIBerty. Carol Stream, IL: Creation House, 1978.