“When nobody else is moving and the students are moving, they are the leadership for everybody.”

Mississippi Civil Rights worker 1963

The Civil Rights Movement in the American South during the 1950s and 1960s involved a diverse group of people. The movement sought legal enforcement of equality for African Americans that was guaranteed by the U. S. Constitution. At various points between 1954 and 1970, participants in the movement represented all strata of American life. White and Black people joined in the struggle, southerners as well as northerners agitated, midwesterners and westerners participated, women along with men protested. Elderly and young Americans were active in the movement as well; however, students from middle school through college came to the struggle much later than most. Not until the 1960s did a substantial number of America's youth join and contribute their efforts to the struggle.

The Pre-Movement Years

In Mississippi, the Civil Rights Movement began slowly and developed unevenly across the state. Civil rights activity in Mississippi before 1955 can best be described as scattered episodes of protest against the denial of voting rights to African Americans. The pre-movement years, from World War II to the mid-1950s, are noteworthy for the early, though often isolated, civil rights activism they fostered. The two most significant organizations to emerge within the state during the pre-movement years were the Mississippi Progressive Voters' League and the Regional Council of Negro Leadership.

Established in 1947 with headquarters in Jackson and branches in Hattiesburg and Cleveland, the Progressive Voters' League promoted itself as a cooperative enterprise that was non-partisan and non-threatening to White people. Its purpose was civic education and participation through motivation and literacy by potentially qualified Black voters. The league's promotion of civic education and its “moderate” posture, according to its president, T. B. Wilson, made affiliation with the league more appealing to Black Mississippians than membership in one of the state branches of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). Despite Wilson's belief in the mass appeal of the Mississippi Progressive Voters' League, the league had a decidedly Black middle-class orientation. But, for segregationists, this made it no less controversial nor less demanding of equal rights and opportunities.

The Regional Council of Negro Leadership was the brainchild of Dr. T. R. M. Howard, a Mound Bayou, Mississippi, African-American physician and businessman who founded the organization in 1951. The programs of the council were described as “midway between…[those] of the NAACP and the Urban League.” In particular, the council supported and actively championed Black voter education, registration, and voting. Additionally, the council campaigned to end police brutality against African Americans. It even targeted White business owners for economic boycotts without directly challenging the segregationist doctrine of “separate but equal.” The organization clearly advocated full citizenship rights for Black Mississippians. Yet the Regional Council of Negro Leadership was not prepared to take on the segregationists in an effort to end “Jim Crow” in Mississippi. The term Jim Crow appears to have originated in 1832 with a song and dance written by Thomas D. Rice. Almost immediately the expression took on racial connotations and became widely used in American literature, especially by southern writers during the latter part of the 19th century. By the first decade of the 20th century, the term was commonly used when referring to the newly emerging southern segregation statutes and race-separate laws.

Viewed together, the early organizing efforts of the Mississippi Progressive Voters' League and the Regional Council of Negro Leadership were essential to the eventual transition from the pre-movement phase of civil rights activism to a struggle in earnest. Evidence of the emerging transition was apparent in Mississippi by 1955. By then the NAACP was the strongest civil rights organization in the state, and it invested resources to organize civil rights activity. To be sure, Mississippi was now regarded as a state where segregation and Jim Crow should be directly challenged. To meet this challenge, the NAACP appointed Medgar Wiley Evers, an Alcorn A&M College graduate and insurance agent in the Delta for Magnolia Mutual Life Insurance Company, as Mississippi's first field secretary of the organization.

Medgar Evers and His NAACP Youth Councils

Evers's early years as field secretary were crucial as he traveled throughout Mississippi organizing and reviving local NAACP branches, meeting with activists, and investigating allegations of injustices against Black Mississippians. Although primarily interested in attracting adults to the civil rights struggle, Evers frequently spent time coaxing youth to join the Civil Rights Movement. As field secretary for the only nationally affiliated civil rights organization in the state, Evers was committed to pressing every advantage, including enlisting the participation of Mississippi's students. Evers, while an Alcorn student, had often traveled from Lorman to Jackson to participate in interracial youth discussions organized by Professor Ernest Bornski at Tougaloo College. These discussions from his college years convinced Evers that students had a role to play in the Civil Rights Movement.

Evers promoted youth participation by establishing student-centered auxiliaries of the NAACP. The most active youth chapters during the 1950s were in Jackson and Hattiesburg. In Jackson, Evers's efforts benefited from the presence in the area of three historically Black colleges and universities — Jackson, Campbell, and Tougaloo colleges. Campbell College later closed and its property was sold to Jackson College for expansion.

Gene Moseley, an NAACP youth council co-chair at Jackson College, remembers student involvement at the time. “There were,” Moseley recalls, “over 200…[Jackson area] youngsters [in the late 1950s] working for the NAACP youth councils.” Unlike Jackson, Hattiesburg was without a local Black college, and although its NAACP youth council had a significantly smaller membership, their activism proved no less zealous. Clyde Kennard, who went on to become the first African American to apply for admission to Mississippi Southern College, now the University of Southern Mississippi, was the NAACP youth council president in 1958. The council also included among its members the Ladner sisters, Joyce and Dorie, who later were youth leaders at Tougaloo College and members of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC).

NAACP youth councils had existed in Mississippi even before Evers's organizing thrust. Some councils predated 1950 and were generally designed to promote “citizenship training for black teenagers…[by] preparing them to register and vote when they come of age.” Additionally, youth council members were afforded travel outside of Mississippi for seminars and other educational experiences that exposed them to African American publications such as Crisis, Chicago Defender, and Amtersdam News. However, most NAACP youth chapters in Mississippi were inactive by the time of the appointment of Evers as field secretary.

The inactivity of most youth councils was indicative of a larger pattern of civil rights underachievement in the 1950s. As Medgar Evers often lamented, it was as if, “Mississippi stood still” while “it was all happening somewhere else.” Evers attributed the lack of change in Mississippi to African Americans who failed to become involved in the struggle and to White Mississippians who staunchly resisted the Civil Rights Movement. The dark and frequently discouraging days of the 1950s gave way to more encouraging and rewarding times of civil rights activism in the 1960s. The reversal of fortune for the Civil Rights Movement during the 1960s was caused by several developments: an increase in the number of civil rights organizations; the use of more effective protest and agitation strategies; and the acceptance by White America of the Civil Rights Movement as a legitimate struggle for social reform.

CORE and Freedom Riders

By 1960 the number of organizations participating in the Civil Rights Movement had doubled from a decade earlier. In addition to the NAACP and the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), created in 1943, the movement had grown to include the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) founded in 1957 by Martin Luther King Jr., and SNCC, a 1960 spin-off of SCLC, which was a student-youth protest organization.

Both CORE and SNCC began sending people into Mississippi in 1961. CORE's initial efforts in the state centered on Freedom Rides. The Freedom Rides involved sending integrated teams of college students into Mississippi (and other Deep South states) on Trailways and Greyhound buses to test the United States Supreme Court decision banning segregation in public interstate transportation. After encountering violence at the hands of a White mob in Anniston, Alabama, the first effort to send Freedom Riders to Mississippi ended abruptly. A second group of riders, consisting of eleven Black people and one White person, made their way to Jackson on May 25, 1961. The group arrived in the early morning hours at the local Trailways bus terminal.

Another team of integrated riders arrived later that day at the Greyhound terminal. Both groups were arrested by local authorities for attempting to use the segregated facilities at the terminals. Throughout the late spring and summer of 1961, teams of Freedom Riders continued to pour into Jackson. Local students immediately embraced the Freedom Riders and became participants in the escalating protest. Protesting Jackson students, like many of the Freedom Riders, were arrested. Most of the youths arrested were secondary school students from the three all-Black high schools - Lanier, Brinkley, and Jim Hill.

Jackson-area students had given indication of their willingness to engage in civil rights protests even before the coming of the Freedom Riders. In 1960, students at Campbell College, led by student body president Charles Jones, organized an Easter boycott of Jackson's Capitol Street white businesses. Jones gave as the reason for the boycott “Blacks' unwillingness to exist as people not yet free.” In the boycott efforts, Campbell College students were supported by their counterparts at Jackson College and Tougaloo College. Interpretations differ as to the success of the boycott — Jones maintained his group's efforts were successful while the White merchants reported the boycott a dismal failure.

The other student protest prior to the Freedom Rides was a read-in at the Jackson Municipal Library by nine Tougaloo College students. On March 27, 1961, the Tougaloo Nine, four females and five males, entered the segregated main branch of the municipal library in search of source material for a class assignment. When the students took seats and began reading, a library staff member called the police. After refusing orders by the police chief to leave the library, the Tougaloo Nine were arrested. The read-in drew support from students at Jackson and Tougaloo colleges as well as Millsaps, a predominantly White college in Jackson. The Tougaloo Nine were charged and convicted of breach-of-peace. Each of them was fined $100 and given a 30-day suspended sentence.

The arrival of the Freedom Riders catapulted Jackson into the national limelight in ways the city's fathers had hoped to avoid. Moreover, in the aftermath of the Freedom Rides, CORE and SNCC quickly expanded in the state, ending the NAACP's longstanding monopoly on civil rights activism. As CORE and SNCC formally moved into the state — Tom Gaithers and Robert (Bob) Moses, their respective field secretaries — the recruitment of young activists became a primary objective.

In its first major project, which took place in Pike County in southwest Mississippi, SNCC heavily recruited local youth. Pike County students Hollis Watkins and Curtis Harris became recruits and were joined by fellow young activists. Marion Barry, for example, was among the SNCC activists organizing in Pike County. Barry was born in the Mississippi Delta and later moved to Washington, D.C., where he was twice elected mayor, first in 1986 and again in 1994. The Pike County projects of SNCC included voter education and canvassing, sit-ins, and even boycotts of public schools. By the end of 1961, SNCC, with some assistance from CORE operatives, had engaged in civil rights organizing in a number of other southwest Mississippi communities.

The difficulties associated with organizing in southwest Mississippi, especially among youth, proved to be a learning experience for Moses. Some of his young recruits were injured in protest activities. Moses came to know first-hand the enormous challenges faced by activists who had to contend with the opposition of segregationists. He was convinced that the situation demanded civil rights solidarity. So the following year, 1962, he proposed that civil rights groups operating in the state form an umbrella organization.

The Council of Federated Organizations, or COFO, was the umbrella agency that emerged. Over the next three years, from 1962 to 1965, COFO either led the coordination of or assisted in civil rights-sponsored activism across Mississippi. As the umbrella organization, COFO was expected to represent and promote the interests of all national, state, and local civil rights groups operating in Mississippi. COFO often included youth mobilization for protest and agitation. Civil rights organizations operating as part of COFO led a large number of sit-ins, protest marches, and boycotts along with voter education, registration, and canvassing drives. These organizing efforts were evident throughout the state from Holly Springs and Marshall County in north Mississippi, to Hattiesburg in Forrest County in the southern tier of the state.

Mississippi Freedom Summer, 1964

In each community, the participation of youth was critical to the movement. Whether the particular civil rights project was in central Mississippi, south Mississippi, or in the northern section of the state, young activists were conspicuous. In the Jackson movement of 1962-1963, the Canton project of 1963, and the many Delta-area protests of 1962-1963, young people were among the movement's most ardent activists. The young activists included not only college students but high school and even some junior high school students.

Student participation in the Civil Rights Movement was best illustrated in the COFO-sponsored Freedom Summer of 1964. That summer, COFO organizers effectively used college students, many from outside of Mississippi, and throngs of younger activists to perform a range of civil rights activities. The activities included, but were not limited to, canvassing communities for voter education and registration, serving as interviewers, teaching in Freedom Schools, and performing various other duties.

For all that students learned and contributed to the movement, their participation was not without its dangers. Students faced increasing violence. Indeed, in early June 1964, a busload of Black Mississippians went to Washington, D.C., to testify publicly about the daily violence and the dangers facing the volunteers coming into Mississippi. Nearly two weeks later, three civil rights workers in Neshoba County were murdered. James Chaney, a young Black Mississippian, and two White volunteers, Andrew Goodman and Michael Schwerner, were killed near Philadelphia, Mississippi.

The 1964 summer protest demonstrated in the most dramatic way the importance of the participation of youth to the civil rights struggle. Arguably the summer of 1964 was the high point of student-youth civil rights activism in the state.

The Struggle Continues

The years following Freedom Summer were ones of re-assessment and change in the Mississippi civil rights struggle. Even so, many young activists remained firmly committed to the continuing push for political and economic empowerment. They were there in most of the major protests and campaigns of the post-Freedom Summer era.

In the COFO-led McComb project of fall 1964, for example, younger activists were especially prominent among the struggle's participants. McComb-area high school students marched and protested with more seasoned activists in support of political and economic empowerment and against the violence of the local Ku Klux Klan. Students were prominent participants in both the 1965 Freedom Democratic Party-led protest at the Mississippi Capitol and the 1966 James Meredith March Against Fear.

The protest at the Capitol in June-July 1965 was directed against the Mississippi Legislature. The state's legislators were in special session to repeal Mississippi's discriminatory voting laws. Even so, the protesters emphasized that the legislators had not been elected by a majority of voting age Mississippians. Protesters contended the legislature was an illegally constituted body, hence violating federal law. On June 14, 1965, approximately 500 demonstrators were at the Capitol and about half of them were teenagers. The teenagers, along with the older protesters, were arrested by Jackson police and transported to the state fairgrounds in paddy wagons and garbage trucks. At the fairgrounds the protesters were incarcerated in facilities usually reserved for livestock.

A year later, on June 4, 1966, the Meredith March Against Fear began in Memphis, Tennessee. It was scheduled to end 220 miles away in Jackson, Mississippi. The purpose of the march, according to Meredith, was to convince African Americans that it was now possible and safe to register and vote by challenging their “all pervasive and overriding fear.” On the second day of the march, Meredith was shot and transported back to Memphis for medical attention. Many notables in the Civil Rights Movement, including Martin Luther King Jr. and Stokely Carmichael, stepped in and continued the march. Along the route through Mississippi many students participated in places such as Grenada, Greenwood, Philadelphia, and Canton. On June 26, 1966, the march concluded at the Mississippi Capitol before an integrated crowd of about 15,000. The crowd, which included many young marchers, heard from King and a host of other luminaries — even the injured James Meredith had rejoined the march to participate in the final 20 miles.

A number of other Mississippi civil rights campaigns materialized in the closing years of the 1960s, all supported by student-youth activists. One of the most important of the campaigns occurred in Natchez. The Natchez Movement, as the civil rights protest was known, eventually evolved into a boycott of local White merchants. The White business community had taken an entrenched position and steadfastly refused to give ground on Black demands concerning hiring, promotion, and other changes in employment practices. The breakdown in negotiations led to a boycott of merchants in which local young people were prominent, especially in picketing targeted businesses.

By the end of the 1960s, students had assembled a record of civil rights activism that spanned well over a decade. During that time their activism was more than symbolic. It was critical, if not essential, to propelling the Civil Rights Movement beyond the general inertia of the 1950s struggle. Student activism, particularly in the 1960s, diversified, energized, and popularized the movement. No longer was the movement only about issues of political and economic empowerment, it philosophically expanded to embrace a broader struggle for human rights as well. Indeed, many of the younger activists were convinced that the movement's real success and enduring legacy lay in sowing the seeds for what they called a “beloved community,” a phrase often used among civil rights activists. The origin of “beloved community” is shrouded in some doubt, but it appears to have gained currency during Freedom Summer 1964. In 1964, discussions among civil rights activists became more frequent about forging an American society based on love and respect for all humanity. Certainly the civil rights activism of students helped to create an America where its tomorrows became less like its yesterdays.

Oral history from the Jackson State Civil Rights Sites Projects, Margaret Walker Alexander Research Center Jackson State University

Percy Chapman

Hillman Frazier

Lucille Green

Hezekiah Watkins

Dernoral Davis, Ph.D., is chairman of the history department at Jackson State University.

Lesson Plan

-

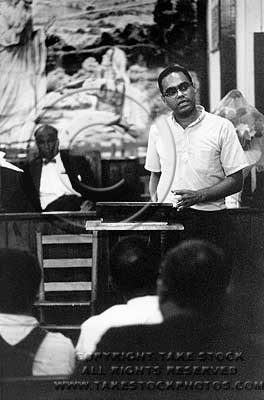

(c)Matt Herron, COFO leader Bob Moses addressing a mass meeting held in a Jackson, Mississippi, church in 1964 -

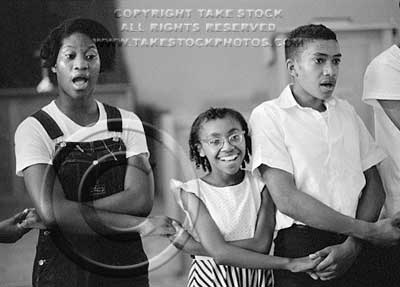

(c)Matt Herron, Young people singing “We Shall Overcome” at a Jackson Youth Meeting, 1963.

-

(c)Matt Herron, June 17, 1965: Mrs. Aylene Quinn, a civil rights activist from McComb, Mississippi, went with her four children to the Governor's Mansion in Jackson to protest the seating of Mississippi congressmen elected from districts where no blacks were allowed to vote. Refused admittance, Quinn and her children sat on the steps of the mansion. They carriedsmall American flags. In this photograph, a Mississippi highway patrolman wrestles American flag from five-year-old Anthony Quinn. -

(c)Matt Herron, James Meredith March, Mississippi, 1966.

Sources and Further Reading

Since 1980 there has been a significant growth in the body of historical literature on the Civil Rights Movement. Listed below are some of the most important and critically acclaimed books and articles.

Books

Sally Belfrage, Freedom Summer, Charlottesville, University Press of Virginia, 1990.

Taylor Branch, Parting the Waters, New York, Simon and Schuster, 1988.

Robert Burk, The Eisenhower Administration and Black Civil Rights, Knoxville, University of Tennessee Press, 1984.

Eric Burner, And Gently Shall He Lead Them: Robert Parris Moses and Civil Rights in Mississippi, New York and London, New York University Press, 1994.

Seth Cagin and Philip Gray, We Are Not Afraid: The Story of Goodman, Schwerner, and Chaney and the Civil Rights Campaign for Mississippi, New York, MacMillan, 1988.

Clayborne Carson, ed., The Student Voice 1960-1965: Periodical of Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, Westport, Conn., Meckler Corporation, 1990.

Vicki Crawford, et al., eds., Women in the Civil Rights Movements: Trailblazers and Torchbearers, 1941-1965 , Brooklyn, Carlson Publishing, 1990.

John Dittmer, Local People: The Struggle for Civil Rights in Mississippi , Urbana, University of Illinois Press, 1995.

Glenn T. Eskew, But for Birmingham: The Local and National Movements in the Civil Rights Struggle, University of North Carolina Press, 1996.

Myrlie Evers and William Peters, For Us the Living, New York, Doubleday, 1967.

David Garrow, Bearing the Cross: Martin Luther King, Jr., and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, New York, Random House, 1986.

Hugh Davis Graham, The Civil Rights Era: Origins and Development of National Policy, 1960-1972 , New York, Oxford University Press, 1998.

Mary King, Freedom Song: A Personal History of the 1960's Civil Rights Movement , New York: Morrow, 1987.

Florence Mars, Witness At Philadelphia, Baton Rouge, Louisiana State University Press, 1977.

Doug McAdam, Freedom Summer, New York: Oxford University Press, 1988.

Kay Mills, This Little Light of Mine: The Life of Fannie Lou Hamer, New York, Dutton, 1993.

Nicolaus Mills, Like A Holy Crusade: Mississippi 1964 --The Turning Point of the Civil Rights Movement in America, Chicago, Ivan R. Dee, 1992.

Anne Moody, Coming of Age in Mississippi, New York, Dial, 1968.

A.D. Morris, The Origins of the Civil Rights Movement: Black Communities Organizing for Change, New York, Free Press/MacMillan, 1984.

Charles Payne, I've Got the Light of Freedom: The Organizing Tradition and the Mississippi Freedom Struggle, Berkeley, University of California Press, 1995.

Fred Powledge, Free at Last? The Civil Rights Movement and the People Who Made It, New York, Harper, 1991.

Belinda Robnett, How Long? How Long? African-American Women in the Struggle for Civil Rights, New York, Oxford University Press, 1997.

Mary Rothschild, A Case of Black and White: Northern Volunteers and the Southern Freedom Summers, Westport, Conn., Greenwood, 1982.

Tracy Sugarman, Stranger At the Gates: A Summer in Mississippi, New York, Hill and Wang, 1966.

C. Vann Woodward, The Strange Career of Jim Crow, New York, Oxford University Press, 1974.

Harris Wofford, Of Kennedys and Kings: Making Sense of the Sixties, New York, Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1980.

Articles

Charles Cobb, “Prospectus for a Summer Freedom School Program,”Radical Teacher, Fall (1991), pp. 36-37.

John Dittmer, “The Politics of the Mississippi Movement,” in Charles Eagles, ed., The Civil Rights Movement in America, Jackson, University Press of Mississippi, 1986.

James Findlay, “In Keeping with the Prophets: The Mississippi Summer of 1964,”The Christian Century, June 8-15, 1988, p. 574.

Steven Lawson, “Freedom Then, Freedom Now: The Historiography of the Civil Rights Movement,”American Historical Review 96, April 1991.

Staughton Lynd, “The Freedom Schools: Concept and Organization,”Freedomways 5, 1965.

A. Meier, “Epilogue: Toward A Synthesis” in Armstead Robinson and Phillip Sullivan, eds., New Directions in Civil Rights Studies, Charlottesville, University of Virginia Press, 1991.

Charles Payne, “The Civil Rights Movement as History,”Integrated Education 26, April 1991.

Daniel Perlstein, “Teaching Freedom: SNCC and the Creation of the Mississippi Freedom Schools,”History of Education Quarterly, 30, 1990.

Carolyn Rickett, “Amite Farm Fought for Something Worth Dyin' For,” McComb Enterprise-Journal, McComb, December 9, 1984.