Electric power has been called “man’s most useful servant.” It heats and cools homes and businesses, cooks and preserves food, illuminates a dark room or street, and powers machinery, televisions, electronics, and transportation.

Electric power was first available in the United States in 1882 when Thomas Alva Edison created the country’s first commercial power plant in New York City. The power plant provided electricity to customers within a square mile. Edison had already developed an incandescent light bulb in 1879 that was practical and safe for home use.

By 1930, nearly fifty years later, 84.8 percent of all U.S. homes in large urban areas and small towns had electrical service, but only 10.4 percent of rural homes had this luxury. In that same year, only 1.5 percent of Mississippi farm homes had electrical lights, the least of any state in the country.

Homes that were wired for electricity for the most part were in densely populated areas where customers used significant amounts of electricity, which was provided by commercial electric utility companies. With power lines costing around $2,000 a mile to build in the mid-1930s, the commercial companies had no immediate plans to service rural areas, thinking that operating costs would exceed potential profits.

Farm life without electricity

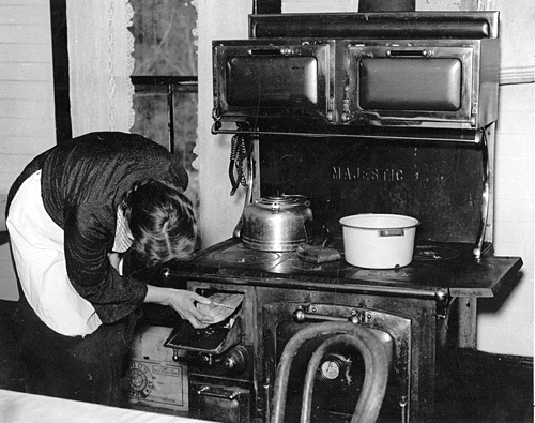

Mississippi farm residents in 1930 completed household and farming chores in the ways of their ancestors without electricity and indoor plumbing. It made work on the farm and in the farmhouse difficult and time-consuming. Doing the laundry, for example, usually took a whole day and a great amount of physical effort. First, buckets of water were pumped from a well, usually located several yards from the house, and heated in a large kettle over a wood-burning fire. A woman then used her hands, usually homemade soap, washboard, and physical energy to clean the family laundry.

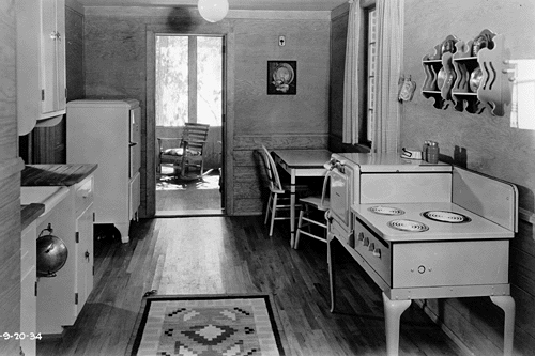

In contrast, women with electricity and indoor plumbing in more urban areas could put the dirty laundry in the washing machine, flip a switch and have hot water flow from the water heater into the appliance. Once full, the washer took care of cleaning the clothes.

Thirty years into the 20th century, the drastic difference between life with electricity and life without it was one factor that encouraged many farm dwellers, particularly young people, to leave the farm behind for life in the city. Other reasons explaining why people left rural America included higher paying jobs, better living conditions, and a life that was not isolated from the world. In the city they could have electricity, own a radio to listen to music, entertainment programs, and news of the day, and have easy access to a social life.

Tupelo – “First TVA City”

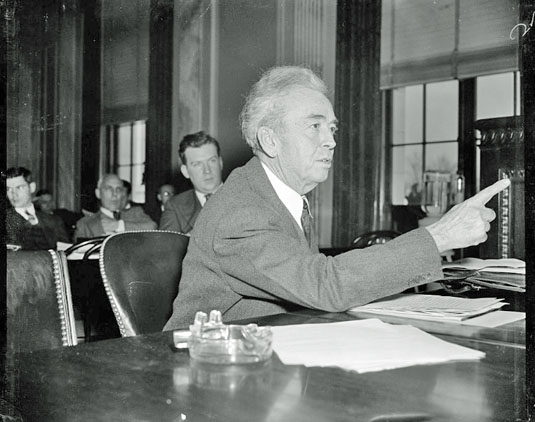

People concerned with improving rural life and decreasing rural-to-urban migration believed electricity was among the most important factors in making rural life more appealing. Senator George W. Norris, a Nebraskan Republican, and Mississippi’s John E. Rankin, a Democrat in the U.S. House of Representatives from 1921 to 1953, were the two most dedicated politicians to the cause of rural electrification. Soon after U. S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt took office in 1933, his administration designed programs to combat the economic problems of the Great Depression, to create jobs to end unemployment, and to improve the lives of average Americans. Norris and Rankin lobbied to include rural electrification in the New Deal programs.

Created by the U. S. Congress on May 18, 1933, the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) aimed to better the living and economic conditions of citizens in seven Southeastern states, including Mississippi. Government officials anticipated improving one of the country’s poorest regions by controlling the Tennessee River, promoting soil conservation practices, increasing non-agricultural jobs, and providing affordable electricity. Thus, distributing electricity created by TVA’s newly constructed dams on the Tennessee River became an early objective of the TVA.

Tupelo, Mississippi, was near TVA’s Wilson Dam in Muscle Shoals, Alabama. The electricity generated by this hydroelectric power plant, which uses falling water to turn generators that produce electricity, was ready for customers. Rankin’s position in Congress resulted in Tupelo becoming the first municipality to purchase TVA power. Tupelo officially became the “First TVA City” in 1934 and the city’s residents could purchase electricity at some of the lowest rates in the United States.

The Corinth Experiment

But the question remained of how to provide electricity to all rural Americans. Federal officials determined that electric power cooperatives, owned by the customers, were the best way to distribute electricity in rural areas. Rural organizations, such as the Grange and Farmers’ Alliance, used cooperative ventures in the 19th century, so this business model was not new to rural Americans.

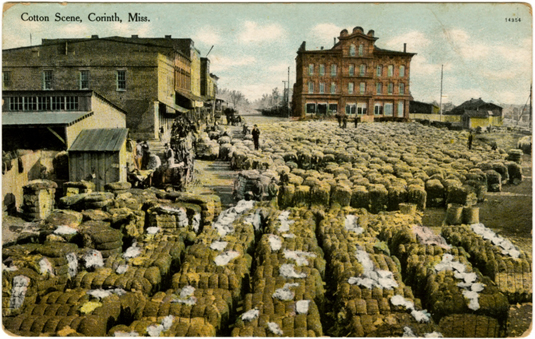

But before establishing a national cooperative system to distribute electrical power, officials wanted to test the model. And they did it in Mississippi through the creation of “The Corinth Experiment” in the form of the Alcorn County Electric Power Association (ACEPA). Congressman Rankin had arranged for a group of Alcorn County businessmen and a TVA official to meet in January 1934 at McPeters’ Furniture Store in Corinth, the county seat. There they established ACEPA, the first electric power cooperative in the United States. The cooperative would be a member-owned organization in which all members would be represented by an elected board of directors. The population of Alcorn County was similar to much of the South—it was dependent on one crop, in this case cotton, and had a high rate of tenant farmers and sharecroppers. Officials believed that if an electric power cooperative could succeed in Alcorn County, Mississippi, it could do so anywhere in the United States.

The federal government provided a loan of $114,632 at a 3 percent interest rate to ACEPA, which it used to fund the stringing of power lines and other start-up costs. People wanting electricity paid a membership fee to the cooperative and committed to using a minimum amount of kilowatt-hours per month. Individuals were responsible for wiring their homes and barns. Although initial estimates indicated it would take the new cooperative thirteen years to pay back the initial loan, in the first year it became clear that it would take less than half of the expected time.

Rural Electrification Administration

In November 1934, President Roosevelt visited Northeast Mississippi. While in Corinth on November 17, he praised citizens for “giving an opportunity to the people who live on the farm [to be] equal with the people who live in the city.” In Tupelo the next day, the president spoke and addressed his critics who did not believe it was the government’s responsibility to provide electricity to its citizens. He stated that the experiments taking place in Northeast Mississippi were grassroots and community-based programs, not a federalization of private enterprise.

The successes of TVA and ACEPA, which Roosevelt observed on his trip, resulted in the creation of an important New Deal program for rural America, the Rural Electrification Administration, or REA. Roosevelt established this program through Executive Order 7037 on May 11, 1935; it would loan money at low interest rates to electrical cooperatives like ACEPA throughout the United States.

Due to the presence of TVA and the work of Congressman Rankin, Northeast Mississippi quickly became one of the nation’s earliest adopters of rural electrification. The Monroe County Electric Cooperative in Amory was the first in Mississippi to provide power to its members with REA funds. Additional electric power cooperatives formed throughout the state and Rankin continued to advocate for rural electrification.

While Rankin could have mentioned how electricity changed the work lives of any of his constituents, he consistently spoke of how electricity improved the lives of women. In his opinion, they gained the most by having access to electricity. During his congressional speeches he spoke of the tough realities of life without electrical power and then quoted letters in which women told him that TVA and REA were “the greatest blessing” and were “the difference between drudgery and luxury.” With electricity “We have just now begun to live,” explained one happy Mississippi woman. Rankin promised to advocate for electricity and better living conditions “as long as I live, whether in public or private life, or until we electrify every farm home in America at rates the farmers can afford to pay.”

Through the examples of the people in Northeast Mississippi, rural citizens across the nation received electricity sooner. And by 1940, 27,670 farm homes in Mississippi had electric lights, a significant increase from 4,792 just ten years earlier.

Sara E. Morris, Ph.D., MLS, is associate librarian for American history, University of Kansas Libraries.

Watch Power and the Land, a 38-minute film of an American farm family before, and after, rural electrification. Produced by Joris Ivens in 1940 for the Rural Electrification Administration, U.S. Department of Agriculture. Film from the Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library, uploaded to YouTube by PublicResourceOrg, August 31, 2010. (Accessed September 2011)

Lesson Plan

-

Early 20th century postcard of cotton ready for the market in Corinth, Mississippi, where "The Corinth Experiment" would be conducted in 1934. Federal officials believed that if an electric cooperative could succeed in Alcorn County with its rural population similar to much of the South, it could do so anywhere in the United States. Courtesy Mississippi Department of Archives and History, Cooper Postcard Collection, Call No. PI/1992.0001/Box 21, Folder 1. -

The streets of Tupelo are lined with Mississippians who greet President Franklin D. Roosevelt and his wife, Eleanor, on their tour of Northeast Mississippi in November 1934. Courtesy Tennessee Valley Authority.

-

Tupelo, Mississippi, the "First TVA City." Courtesy Northeast Mississippi Daily Journal. -

The TVA powerhouse in Tupelo, Mississippi, in 1935. Courtesy Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, LC-USF33-002054-M2. -

Electricity made farm work easier and less time-consuming. Farmer seen here with an electric feed grinder in 1930s. Courtesy Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library, New Deal Network. -

Before electricity was available to rural homes, the family laundry was an all-day task done by hand. Courtesy Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library, New Deal Network. -

Women with electricity in more urban areas in the 1930s could load the laundry in a washing machine, flip a switch to have hot water flow into the appliance, and the machine cleaned the clothes. Courtesy Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library, New Deal Network. -

An example of a cooking stove used before electricity was available to rural areas. Courtesy Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library, New Deal Network. -

A 1934 farmhouse kitchen after installation of electric appliances. Courtesy Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library, New Deal Network. -

U. S. Congressman John Rankin of Mississippi testifies before a Joint Congressional Committee in December 1938 that TVA power had resulted in an annual saving of $556,000,000 to consumers of electricity. Rankin co-authored the Tennessee Valley Authority Act. Courtesy Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, LC-H22D-5158.

References:

Born, Emily. Power to the People: A History of Rural Electrification in Indiana. Indianapolis: Indiana Statewide Association of Rural Electric Cooperatives, 1985, pp. 14-16.

Brown, D. Clayton. Electricity for Rural America: The Fight for the REA. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1980.

Roosevelt, Franklin D. The Public Papers and Addresses of Franklin D. Roosevelt. The Public Papers of the Presidents of the United States, University of Michigan Digital Library. (Accessed September 2011)

United States Congress. Congressional Record. Washington, D.C. Government Printing Office.

United States Department of Commerce. Bureau of the Census. Historical Statistics of the United States, Colonial Times to 1970s. White Plains, NY: Kraus International Publications, 1989.