During the early 1900s, the boll weevil threatened the Yazoo-Mississippi Delta and put the state’s cotton kingdom in peril. Surprisingly, planters believed that the best way to defend their cotton from the weevil was to protect their place on top of the racial and social ladder in the Delta. James Giesen’s research reveals the ways in which the beliefs of White landowners concerning race and labor shaped the approach of Delta planters to their agricultural environment and its pests. Giesen is the author of “’The Truth About the Boll Weevil’: The Nature of Planter Power in the Mississippi Delta,” Environmental History 14, no. 4 (October 2009): 683-704, from which this article has been condensed. – Editor’s note

A profound threat to the Delta “promised land”

In late 1908, Mississippi Delta planter LeRoy Percy wrote a friend about the approaching cotton boll weevil. Sixteen years earlier, the insect pest had appeared in Texas and begun a slow march toward Percy’s fields. As the weevil drew near, Percy worried that his family’s Delta cotton kingdom teetered on the brink of destruction. “Without question,” Percy wrote, “the weevil will bring with him disaster.”

There was legitimate cause for Percy’s dismay. The pea-sized beetle, which was present in the cotton fields of five states, could already be blamed for staggering losses: four million bales of cotton valued at roughly $238 million in 1908 (approximately $6 billion in 2015 currency values). Farmers and government scientists had discovered what made this pest so damaging. The boll weevil was dependent on cotton at every stage of its life. The insects fed on the plant’s fibers, laid eggs in its squares, grew in its enclosed buds, and hibernated on the edges of its fields. Of the weevil’s four life stages (egg, larva, pupa, and adult), it lived three inside the plant itself. Poisons were ineffective because the pest spent most of its life nestled inside the square of the cotton plant where it was safe from insecticides that were applied only to the outside of the crop. Moreover, the top weevil expert at the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) wrote in 1907 that the alluvial areas of the Mississippi Delta might prove to be the weevil’s “promised land.”

Transformation of land and labor in the Delta

There was no region of the country, perhaps the world, more devoted to mass production of cotton than the Mississippi Delta. By the dawn of the twentieth century, Mississippi landowners had transformed the Delta from an uninhabitable swamp into a modern, agricultural environment characterized by generous farmland, few landowners, and an abundance of African American labor. Cotton divided Delta society between those who owned land and those who merely worked it (e.g., sharecroppers and other tenant farmers). Nearly all of those who owned the land were White, while the vast majority of those who worked the land were Black.

It was clear to Percy and the rest of the planter elite that the approaching boll weevil was a profound threat not merely to their cotton plantations, but more importantly, to the social and economic system of the Delta that rested on the plant’s growth. The boll weevil was a danger both to planter power and to the very fabric of the human relationships that planters believed they controlled. The insect might as well have been a devourer of paper money or tenant contracts as of the cotton plant itself.

“Controlling the fight”: Delta society and labor

Examining the history of the boll weevil’s arrival in the Mississippi Delta sheds light on the complicated relationship between the agricultural environment, society, and economic power in the early twentieth century South. Dealing with farm laborers had always been more important to the planter’s fight against the natural world than their understanding of forests, soil, finance, or even the cotton plant itself. Under threat by the advancing insect pest, these landowners thought first of retaining control of the farm workforce. For planters, beating the boll weevil didn’t mean killing it. It did not even mean keeping their cotton safe from the pest’s harm. Instead, winning this latest war against nature meant controlling the fight against the boll weevil.

Managing the region’s defense against the pest on their terms meant that planters could afford to let the weevil destroy literally tons of cotton. These planters could economically withstand a few years of crop losses, but what they could not survive was a revolution by their largely African American workforce and the dismantlement of their traditional plantation structure. Elite planters calculated that the unique natural assets of the Delta—its soil, climate, topography, and geography—would eventually resist the weevil, but if the vast labor force left the area, the plantation kingdom could never recover. Planters were right. The weevil’s devastation of cotton was short-lived, tenants stayed, and the dreaded revolution in the Delta agricultural environment did not materialize.

The preparation of large landowners for the arrival of the boll weevil offers a window into the process by which landowners’ environmental beliefs shaped the treatment of farm labor during a specific, but dynamic, historical moment. The region’s landowners defined this insect enemy as a human dilemma and favored solutions to the boll weevil problem that fit into their understanding of labor and the uniqueness of the Delta environment. These planters believed that if knowledge about the pest was made public, it would “panic” sharecroppers and other tenant workers, and thousands of African American laborers, upon whom a successful, profitable crop relied, would leave the Delta.

“Dire consequences”: planters’ attempts to control labor

Central to the South’s difference from the rest of the country in the early twentieth century were the roles played by farm laborers and race. This boll weevil story offers a glimpse into how powerful landowners thought about the connections between the vast plantations they owned and the people living and working there, who were mostly formerly enslaved people or their children.

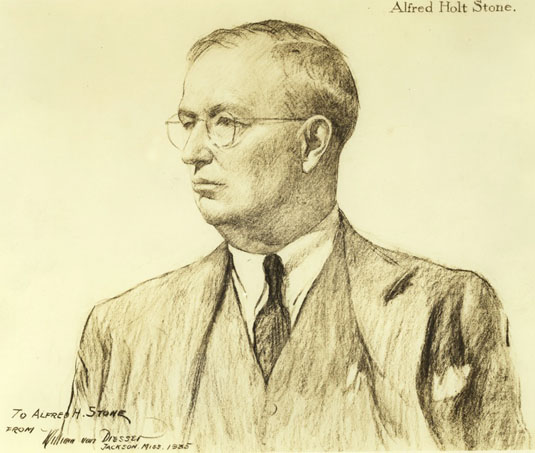

For many Delta planters like Alfred Holt Stone of Washington County, the Black labor force and the physical environment of the Delta were equally important to its future as a cotton kingdom. He knew them to be inextricably linked, almost one and the same. He rarely spoke of African Americans without mentioning nature, and vice versa. In a 1902 paper published by the American Economic Association, Stone explained how the natural gifts of the Delta’s physical world owed its environmental transformation to the work of Black Mississippians. “Its forests have been cut out by the negro,” and the levees “erected mainly by the negro.” While “[t]he capital, the devising brain, the directing will, constitute the white man’s part,” Stone conceded, “the work itself is the negro’s.”

Relying so heavily on Black labor, however, did not come without its problems, but for Stone these were not the same issues that other southern regions faced. While the rest of the nation grappled with the “negro problem,” Stone observed, in the Delta “we hear nothing about an ignorant mass of negroes dragging the white man down.” “We have but one negro problem,” he claimed, “how to secure more negroes.”

Delta planters’ obsession with an adequate labor supply was not unfounded. Historically, a great number of sharecroppers and renters in the cotton South moved at the end of every season, but in the three years leading up to the weevil’s 1909 entry into the Delta, there was a remarkable new influx of workers. Ahead of the encroaching pest, thousands of cotton laborers moved from weevil-plagued regions to the Delta in an effort to escape the insect’s damage. One Greenville paper identified an “EXODUS OF NEGROES” from the boll weevil territories. In southern Mississippi, where the pest was causing significant damage, “the negroes refuse to listen to the appeals of the [local] planters,” and as a result “2,000 negroes have moved…into the Delta.” The paper predicted just what planters feared most, that the boll weevil had pushed workers into the region, and it would soon push them out.

Alfred Holt Stone encountered some of these migrating workers, but his ensuing statements contained a foreboding of fear. If workers could so easily leave one cotton-growing region for another, Stone wondered, what would keep these workers in the Delta once the boll weevil arrived? For Stone and his neighbors, the answer was to worry first about keeping workers on their land. “We cannot make cotton without labor,” the planters argued, “and we cannot hold our labor if we pursue the suicidal policy of not only becoming frightened ourselves, but of showing our fright to our negroes.”

Landowners’ perception of sharecroppers—their deep-seated White supremacy based on a “natural” understanding of racial hierarchies—shaped their treatment of the landscape, which in turn affected their employment of Black labor. Planters endeavored to keep growing cotton because men and women in their employ had transformed their land into a cotton-producing “promised land.” Delta planters, like other southerners and some historians, used the environment as a way to defend southern distinctiveness. Through the 1910s and 1920s, they observed the boll weevil’s devastation of cotton crops in other parts of the South and saw this as evidence of the Delta’s uniqueness. Their singular faith in their land and the men and women who shaped and re-shaped it, guided their plantation operations well into the twentieth century, through floods, drought, and depression.

Planters learned in the fight against the boll weevil that controlling information about the natural world was an effective means for controlling the people who worked it. This approach was one they would return to again and again. Ultimately, there is much that can be learned from the weevil’s Delta invasion and how these marauding insects exposed the extent to which landowners’ beliefs about nature were inseparable from their views on race, society, and economic power.

James C. Giesen is an associate professor of history at Mississippi State University. He also serves as executive secretary of the Agricultural History Society, and series editor of the Environmental History and the American South Series published by the University of Georgia Press.

Other Mississippi History NOW articles:

-

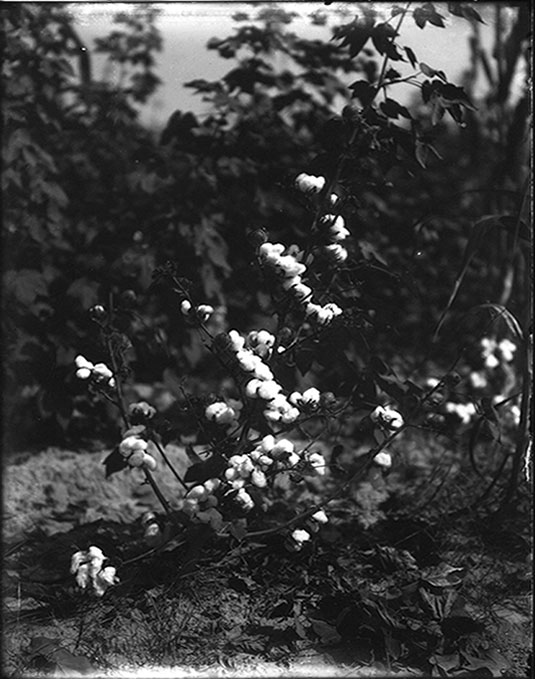

A close view of a stalk of cotton. Photograph courtesy of Mississippi Department of Archives and History, PI/1997.0006.0470. -

Cotton squares infested by the boll weevil during the larva and adult stages of the insect’s life cycle. Courtesy of Mississippi Department of Archives and History, Farm Bureau Federation Collection, PI/2010.0002.

-

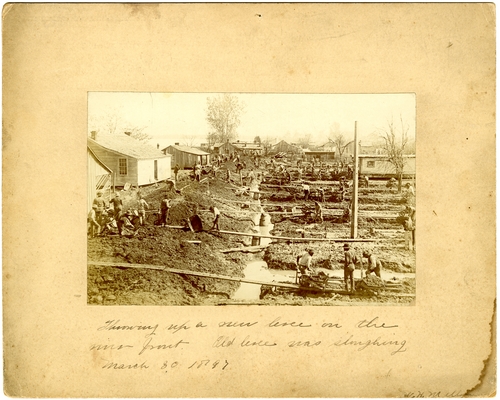

African American laborers work to repair a levee on the river front in Greenville, Washington County, Mississippi, in 1897. Courtesy of Mississippi Department of Archives and History, Coovert (J.C.) Photograph Collection, PI/1900.0017. -

African American farmers pick cotton in the Mississippi Delta during the 1890s. Courtesy of Mississippi Department of Archives and History, Coovert (J.C.) Photograph Collection, PI/1900.0017. -

Alfred Holt Stone (1870-1955)Planter, collector, tax commissioner.1935 drawing by William Dresser. ??Courtesy of Mississippi Department of Archives and History, Stone Collection, PI/1999.0001??.

Sources and suggested readings:

Giesen, James C. Boll Weevil Blues: Cotton, Myth, and Power in the American South. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2011.

Giesen, James C. “’The Truth About the Boll Weevil’: The Nature of Planter Power in the Mississippi Delta.” Environmental History 14, no. 4 (October 2009): 683-704.

Harris, J. William. Deep Souths: Delta, Piedmont, and Sea Island Society in the Age of Segregation. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2001.

Hollandsworth, James G. Portrait of a Scientific Racist: Alfred Holt Stone of Mississippi. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2008.