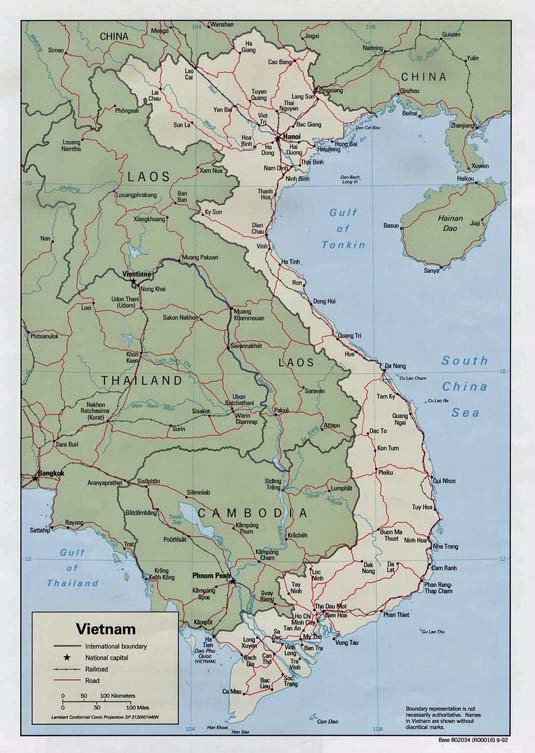

The fall of the South Vietnamese capital, Saigon, to Communist forces in 1975 marked the end of thirty years of American involvement in the Vietnam War. Since the late 1940s, the United States had attempted to contain the spread of Communism in this region, and after 1954 had supported the division of the country into Communist North Vietnam and non-Communist South Vietnam. It was complicated, however, by home-grown Communists in South Vietnam who waged a civil war to achieve unification with North Vietnam.

The first significant U.S. involvement in Southeast Asia came during the Harry Truman administration when the United States provided military aid to French forces fighting the Communists, but it was under President Lyndon B. Johnson that large numbers of American ground troops were sent to fight in Vietnam.

The Vietnam War touched nearly everyone in Mississippi. As they had done in all American wars, Mississippians served in Vietnam with pride and honor, and 637 returned home under a flag-draped coffin, having paid the ultimate sacrifice. Twelve Mississippians are still listed as Missing in Action. Two Mississippians, Ed W. Freeman (1927-2008) and Roy M. Wheat (1947-1967), were awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor for their valor in Vietnam.

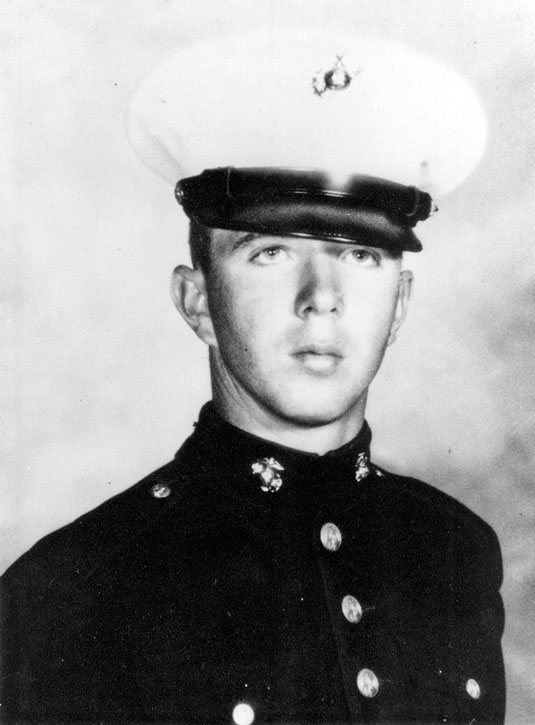

Captain Freeman’s exploits with the First Cavalry Division were depicted in the 2002 film, We Were Soldiers. On November 14, 1965, Freeman flew fourteen helicopter rescue missions into intense enemy fire in the Ia Drang Valley in order to evacuate an estimated thirty seriously wounded soldiers. Born in Greene County, Mississippi, Freeman retired from the U. S. Army in 1967, settled into his wife’s home state of Idaho, and flew helicopters for the U. S. Department of the Interior.

Lance Corporal Wheat of the First Marine Division, a native of Moselle, Mississippi, was killed in action on August 11, 1967, when he threw himself upon a mine, taking the impact of the explosion and saving fellow marines from certain injury and possible death. In 2003, the U.S. Navy christened a prepositioning ship the USNS LCPL Roy M. Wheat (T-AK-3016) in his honor.

Ships and bases

The state also contributed hardware to the war effort. Vessels from Pascagoula shipyards prowled the waters off Southeast Asia. The tank landing ship USS Washoe County (LST-1165), built by Ingalls Shipbuilding saw action throughout the war, earning numerous citations and twelve battle stars for her service in Vietnam. In March and April 1966, she participated in Operation Jackstay, the first joint United States-South Vietnam amphibious assault of the war designed to protect the vital shipping corridor to Saigon.

Keesler Air Force Base in Biloxi trained 743 South Vietnamese pilots in the T-28 Trojan, a fighter aircraft used by the South Vietnamese Air Force during the war. At Camp Shelby in 1966, the 199th Light Infantry Brigade received combat training in such areas as escape and evasion training. When the soldiers left Mississippi, the community saluted the soldiers with an event in the Reed Green Coliseum at the University of Southern Mississippi.

Also during the Vietnam War, the Strategic Air Command’s 454th Bombardment Wing operated from Columbus Air Force Base. The base’s B-52 bombers and KC-135 tankers performed more than one hundred bombing missions during the Vietnam War and did not lose a single aircraft.

The Meridian Naval Air Station also played host to many military personnel who went on to serve in Vietnam. Indeed, at the Meridian Naval Air Station the dining facility for enlisted personnel is named for Roy M. Wheat.

Mississippi protest

The Vietnam War generated massive antiwar demonstrations throughout the United States, including Mississippi. The reasons for Mississippians’ protests were as varied as the people of the state.

Some Black Mississippians viewed the all-White draft boards and military recruiting efforts as racially biased. By the mid-1960s, African Americans were 11 percent of the United States population, yet made up almost 14 percent of the military forces in Vietnam, and at one point accounted for 15 percent of the casualties. Some White Mississippians could lessen their chances of serving in Vietnam by joining the National Guard but such options were open to those of wealth or political connections. At one point, of the more than 10,000 members of the Mississippi National Guard, only one was Black.

Moreover, Robert McNamara, secretary of defense, introduced Project 100,000 in the mid-1960s to bolster military recruitment. Rather than call up military reserve units or abolish student deferments from the draft, which might stir up further anti-war protests, Project 100,000 was established as a remedial education program designed to bring in 100,000 poor and poorly educated new recruits each year. Eventually more than 300,000 soldiers were recruited — 50 percent served in Vietnam; 37 percent were put directly in combat situations. It is unknown how many low-income, under-educated citizens of Mississippi saw service because of Project 100,000.

Other Mississippians protested for additional reasons. Civil rights activist Fannie Lou Hamer of Ruleville shared the concerns of many in the nation and worried that the war would distract from domestic concerns, including the civil rights movement. In March 1965, students from Tougaloo College launched a march through downtown Jackson from the Mississippi Freedom Democrat Party (MFDP) headquarters. Later that same month in the Sidon community of Leflore County, a MFDP-sponsored prayer meeting against the war was held in the Newton Chapel Church. The church was burned to the ground shortly after the meeting. In the 1966 mid-term elections, the MFDP called for an end to the Vietnam War. Ulysses Nunnally of Holly Springs tried to file a lawsuit against the all-White draft boards.

Sometimes protests boomeranged and produced unintended damage. The MFDP newsletter reprinted a leaflet from McComb civil rights activists Joe Martin and Clint Hopson that listed five reasons why Black Mississippians should not fight in any war for a country that does not recognize their rights at home. The men’s anger came from the death of John Shaw, a former Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee activist, who was killed in Vietnam in July 1965. The newsletter had not endorsed the leaflet but it had published earlier letters opposing the war. Critics of the MFDP seized upon the newsletter, citing unpatriotic language. Criticism even came from other Black leaders. In the end, the MFDP distanced itself from the leaflet but again pointed to the contradiction of Black Mississippians fighting overseas for freedoms not available to them at home.

On February 24, 1967, angry crowds, composed of Tougaloo College students and other protesters, confronted McNamara during his visit to Jackson. One of their signs read, “Students can’t abide McNamara’s genocide!” In 1968 and 1969, University of Mississippi students protested the required Reserve Officers’ Training Corps, or ROTC, by boycotting drill and verbally harassing those who did attend. Three student protesters were sent home. Also in 1969, Ole Miss officials successfully used the courts to block Earle Reynolds, Ph.D., a Quaker antiwar activist, from speaking on campus. A federal marshal served the papers to Reynolds during his March 14 classroom presentation, stopping him mid-sentence.

Politicians and the Vietnam War

Mississippi congressional politicians played key roles in war policy, linked the fight to ongoing civil rights struggles, and helped heal national wounds afterwards. The views of Senator John C. Stennis, who served in the U. S. Senate from 1947 to 1989, and chaired the Senate Armed Services Committee from 1969 to 1980, changed over time. In the early 1950s, Stennis expressed concern to the Dwight Eisenhower administration about what he saw as an open-ended American escalation. By the 1960s, as American involvement increased and the war dragged on, Stennis grew frustrated at the political limitations placed upon the military strategy in Vietnam. He complained of a lack of political will to fight the war to a successful conclusion and called for the United States to expand efforts and fully commit to victory.

U. S. Senator James Eastland, who represented Mississippi from the early 1940s until 1978 and chaired the powerful Judiciary Committee for many years, was a passionate anti-Communist. He equated the war against Communism in Vietnam with the struggle against the civil rights movement at home, whose leaders he tarred as Communists. He favored legislation targeting certain antiwar protesters. Like Stennis and other southern senators, he sought military victory in Vietnam. He later recalled a conversation with President Johnson in which he criticized the president’s policies: “that’s what a number of we Southerners were arguing with him about, because we didn’t blow the fire out of North Viet Nam.”

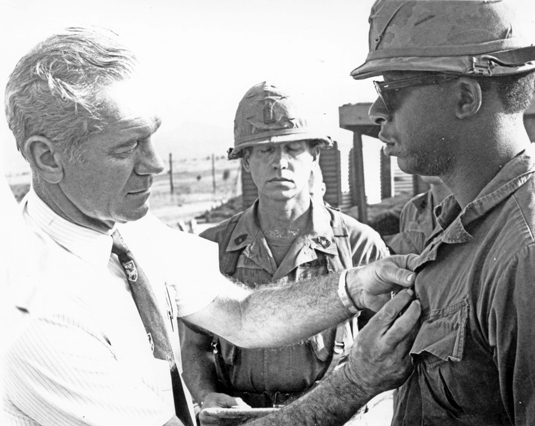

Congressman Gillespie V. “Sonny” Montgomery, a thirty-five year military veteran from Meridian, Mississippi, served in the U. S. House of Representatives from 1967 to 1997. He made twelve fact-finding trips to South Vietnam during the war. Afterwards, he made four additional trips to what had been North Vietnam in efforts to determine the fate of missing members of American military forces. Montgomery chaired the Select Committee on Americans Missing in Action in Southeast Asia, which eventually determined that no Americans remained as captives in Southeast Asia.

Mississippi moves right

The Vietnam War helped push Mississippi to the political right. Many in the state grew angry with the national Democratic Party as the war dragged on with no end in sight. The Republican Party, for years calling itself the stronger anti-Communist party on foreign policy, made gains in the state. While other issues also influenced the vote, in the presidential elections during the Vietnam War Mississippians voted for the candidate with the more hawkish stance on the conflict: 87 percent to Barry Goldwater in 1964; 63 percent to George Wallace in 1968; and 78 percent to Richard Nixon in 1972. After the war, Mississippians gravitated towards politicians such as Ronald Reagan who promised to return the United States to a position of international strength after the failure of Vietnam. By 2009, Mississippi had become recognized as one of the strongest Republican states in presidential elections, a journey that began with opposition to the civil rights movement and strong support for military victory in Vietnam.

Memorials to Vietnam War veterans

Today monuments honoring Mississippians who served in the Vietnam War dot the state. Most are simple plaques, listing area citizens who served in the war, usually found on courthouses grounds. The largest memorial to Mississippi Vietnam veterans sits on four acres in Ocean Springs. Dedicated in 1997, the granite, limestone, and concrete Mississippi Vietnam Veterans Memorial began as an idea of Vietnamese-Americans.

By the early 1990s, some 10,000 Vietnamese-Americans inhabited the Mississippi Gulf Coast, having migrated to the area over the previous decade. The Vietnamese-Americans, displaced by the war and its aftermath, wanted to show their appreciation for the Mississippians who had fought and died for South Vietnam. The Mississippi Vietnam Veterans Memorial presents both the names and images of those from the state who served in the war, including those still listed as missing. It is a fitting monument to the men and women who served in Vietnam and adds to the rich narrative of Mississippians and the Vietnam War.

Toby G. Bates, Ph.D., is an assistant professor of history, division of arts and sciences at Mississippi State University – Meridian.

-

Perry-Castaneda Library Map of Vietnam. Courtesy University of Texas Libraries, The University of Texas at Austin. -

Ed W. Freeman (1927-2008) was awarded a Congressional Medal of Honor for his helicopter rescue missions in Vietnam. Courtesy Mississippi Armed Services Museum, Camp Shelby, Mississippi.

-

Lance Corporal Roy M. Wheat (1947-1967) was awarded a posthumous Congressional Medal of Honor for giving his life in Vietnam to save other marines. Courtesy Mississippi Armed Services Museum, Camp Shelby, Mississippi. -

In 2003, the U. S. Navy christened the 864-foot-long Prepositioning ship the USNS LCPL Roy M. Wheat in honor of Lance Corporal Roy M. Wheat who was killed in action in Vietnam. Courtesy U. S. Navy. -

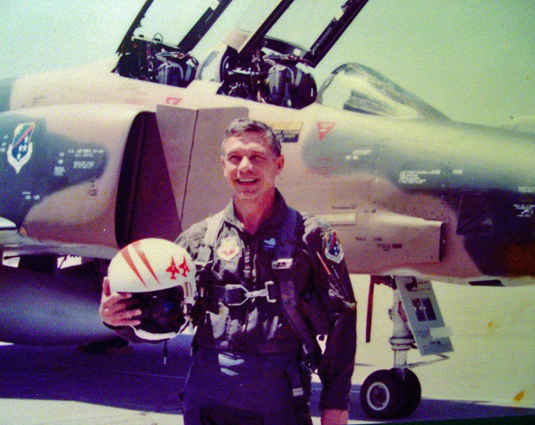

Mississippian and Air Force Colonel George Robert Hall served in Vietnam from 1963 to 1973, most of that time as a prisoner of war. Col. Hall was shot down over North Vietnam in 1965 and held for seven and a half years in the infamous "Hanoi Hilton" prison camp. Courtesy Mississippi Armed Services Museum, Camp Shelby, Mississippi. -

In 1966 the 199th Light Infantry Brigade received combat training at Camp Shelby near Hattiesburg, Mississippi. Courtesy Mississippi Armed Forces Museum, Camp Shelby, Mississippi. -

Columbus Air Force Base housed B-52 bombers during the Vietnam War. The 454th Bombardment Wing operated out of the base and performed more than 100 bombing missions during the war. Courtesy Columbus Air Force Base. -

On July 4, 1968, senators John C. Stennis (D-Miss.) and Henry M. "Scoop" Jackson (D-Wash.), with unidentified military personnel, arrived to tour the Malmstrom Air Force Base in Montana. Stennis chaired the Senate Armed Services Committee from 1969 to 1980. Courtesy Congressional Political Research Center, Mississippi State University Libraries, John C. Stennis Collection. -

The Vietnam Veterans Memorial, or "the Wall," in Washington, D.C. Dedicated in 1982, it was designed by Maya Ying Lin. Courtesy TheWall-USA.com -

Mississippi Congressman G. V. "Sonny" Montgomery made 12 fact-finding trips to South Vietnam during the war. Here he pins a medal on Sgt. William Beldace in December 1970. Courtesy Congressional Political Research Center, Mississippi State University Libraries, G. V. "Sonny" Montgomery Collection, CPRC. -

Mississippi Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Ocean Springs, Mississippi. The Vietnamese-Americans along the Mississippi Gulf Coast proposed the memorial to show their appreciation for the Mississippians who fought and died in Vietnam. Dedicated in 1997, the memorial was designed by architects Farral D. Hollomon and Mark S. Vaughan. Photograph by Ray L. Bellande, 2009.

References

Asch, Chris Myers. The Senator and the Sharecropper: The Freedom Struggles of James O. Eastland and Fannie Lou Hamer. New York: The New Press, 2008.

Cohodas, Nadine. The Band Played Dixie: Race and the Liberal Conscience at Ole Miss. New York: The Free Press, 1997.

Dittmer, John. Local People: The Struggle for Civil Rights in Mississippi. Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1994.

Downs, Michael S. “Advice and Consent: John Stennis and the Vietnam War, 1954-1973.” The Journal of Mississippi History, Volume LV, Number 2, (May 1993).

Herring, George. America’s Longest War: The United States and Vietnam, 1950-1975, 4th Edition. New York: McGraw Hill, 2001

Montgomery, G. V. “Sonny” with Michael B. Ballard and Craig S. Piper. Sonny Montgomery: The Veteran’s Champion. Mississippi State University Libraries, 2003.

Time magazine, May 25, 1970.

Mississippi Armed Forces Museum, Camp Shelby, Mississippi

A Brief History of Keesler Air Force Base and the 81st Air Force Wing