The ferocity of Hurricane Katrina etched the date August 29, 2005, in the minds of everyone who experienced it. South Mississippians, and the thousands of people from across the country who came to their aid, are forever shaped by the disaster and its aftermath.

Katrina made landfalls in southeast Florida and Buras, Louisiana, before it slammed into the Mississippi Gulf Coast near the mouth of the Pearl River as a Category Three hurricane around 10:00 a.m. that fateful Monday.1 The hurricane brought top winds estimated at 125 miles per hour and an estimated thirty-foot-high storm surge that penetrated at least six miles inland in some sections of the coast, and up to twelve miles inland along bays and rivers. It was a massive storm—it had a 25-mile to 30-mile radius of maximum winds and a wide swath of hurricane force winds extending at least 75 miles to the east along the Mississippi coast. Throughout the morning, Katrina weakened while slowly moving inland into southern and central Mississippi, becoming a Category One storm by 1:00 p.m. About six hours later, it weakened to a tropical storm just northwest of Meridian, Mississippi.

In its wake, Katrina left mass destruction, widespread confusion, and unforeseen human misery—49 counties in Mississippi were declared federal disaster areas (See FEMA map). According to the 2000 census, 1,931,619 people lived in those counties—363,988 people lived in the three counties along the shoreline of the Mississippi Gulf Coast where about 158,000 houses were damaged or destroyed. More than 225 deaths in Mississippi were a direct or indirect result of Katrina, yet the exact figure may never be known. Although Hurricane Katrina will be remembered as the costliest and most destructive storm in the nation’s recorded history, what can be lost and forgotten is the individual and personal experience of the storm. How did the power of Hurricane Katrina manifest itself in the lives of the people in the path of the storm?

In September 2005, The Center for Oral History and Cultural Heritage at the University of Southern Mississippi, through the support of the Mississippi Humanities Council and with the help of several participating scholars, began to record personal narratives of Mississippians still reeling from the storm. Historians are much more accustomed and comfortable in dealing with subjects from a distance, both chronologically and emotionally, yet post-Katrina there was an urgency to document how individuals and each distinct community along coastal Mississippi had endured and persevered.

Hurricane Katrina is a phenomenon with which nearly a year later many coast residents are still learning to cope with on many levels, from restoring shelter, to working with government agencies and insurance companies, to dealing with a sense of grief and loss. Recording their stories now, however, is of the utmost importance. As the history of the experiences with Katrina is being formed in the media and the collective public memory, the personal oral histories offer authentic and true portraits of the storm. For Mississippians, many of whom feel their story was lost with national attention focused on the levee break in New Orleans and the resulting tragedy there, recording their experiences is a means to recognize and validate what they endured. Katrina stories run the scope of the human experience, from fear and courage to tragedy and humor. These narratives, individually and as a whole, are part of the healing process, the need to understand what occurred, and to garner hope for the future.

Weathering the storm

Katrina joins hurricanes Camille, Betsy, and the Hurricane of 1947 as landmarks in the modern history of the Mississippi Gulf Coast. Each storm stands as a rite of passage for the generations that have called the coast home.

As Mississippians think back on their experiences with Hurricane Katrina, they recall the point at which they realized that this was not just an ordinary storm. U.S. Navy veteran and Moss Point resident Eric Jones describes being awakened in the early morning hours of August 29 by the power of Katrina’s winds:

Well, I remember that night, I guess it was about 1:30, 2:00 in the morning, and the rain’s really coming down, you know, the wind is blowing in, you could hear it hitting like golf balls against the house and the windows and stuff. We still had power at that time. Early, I guess about 5:00, 5:30, you’d hear limbs breaking, garbage cans, and everything that wasn’t secured by different people, slapping and moving. It woke me up about, I guess about 5:30. So I said, “OK, let me see how it’s looking,” and I kind of opened the door —I have a big glass door—and the door was really, it had like a suction on it. I said, “Oh, Lord,” you know, kind of “I better not open this door” . . . – Eric Jones, Moss Point

During the storm, Joel Ellzie, special needs coordinator with the Hancock County Emergency Management Services, helped man the telephones at the Emergency Operations Center in Bay St. Louis, south of Highway 90. Ellzie remembers his words to three co-workers after receiving a sobering call while he is standing in eighteen inches of water that the worst was yet to come:

And I told them, I said, “Guys, this is what they’re saying.” And at that point when we got off the phone, the phones were dead and that was it. Cell phones didn’t work. Radios didn’t work. Telephones were gone. Power was out. TV was gone. So we had lost all communications at that point. And I told them what they had told me. So we gathered everybody in the room where we were in the water and told everybody, asked everybody, said, “Now, just start counting off numbers.” And everybody started, counted a number, you know, one through thirty-five. And we got a sheet of paper and wrote number one, and that person wrote their name out beside it; number two, and that person wrote their name out beside it. I was number eighteen and I wrote my name out beside it. Got the list filled and we put it in a heavy-duty Ziploc bag, waterproof bag, and we nailed it to the top of the roof so that if something did happen, if we did have ten feet of water come through and something did happen to us, they would have a list of who was in there. And we got a waterproof Magic Marker and wrote the numbers on our arms so that they could have an identifying mark. – Joel Ellzie, Bay St. Louis

Pamela Berry, intensive care unit nurse at Gulf Coast Medical Center in Biloxi, worked against tremendous odds, securing critical patients in a hallway away from shattered windows and fallen ceilings while the storm raged on. Here, she recalls seeking a moment of reprieve, only to be shaken again:

You know, we didn’t have any power or water, but the worst was the patients. We ran out of oxygen, but eventually there were—probably about 10:30 it was just, it was at 10:30 that morning, by that time we were having to get in the hallways. Well, let me back up a little bit. I had been up for like thirty-six hours at that point. No sleep since Saturday night because of just trying to get ready and everything. I was absolutely exhausted and, hurricane or no hurricane, I wanted to lay down somewhere and get some sleep. The problem was there wasn’t anywhere to lay down because there was water all over the floor. And so I just, I left the hallway. I said, “I’ve got to find somewhere to lay down.” So I went into a room. The window wasn’t blown out and so I was like, “Well, I could get up on this bed but that’s probably not smart because something’s going to come through that window.” And then I was like, “Well, I could get on the floor over here but the floor’s kind of wet.” I said, “Well, I can go in the bathroom.” So inside the bathroom in the shower stall there was like a little, you had to kind of step into the shower. So the shower, the bottom of the shower stall, was dry. I said, “There’s my bed.” So I went and found a dry blanket and made me a little pallet in the bottom of that stall and I was just going to sleep, even if I could just get like a twenty-minute nap because I was so tired. And I had just gotten comfortable and I felt that whole building move. I mean, it just moved. I don’t know if that’s when the storm surge hit it but I stood, you know, and I just prayed. I said, “Well, this is it. This whole building’s going to fall down.” I wasn’t worried about it blowing over as much as I was just collapsing, like the fifth floor falling on the fourth and the third. But, you know, I just prayed and said, “Well, this is it, Lord. I’m ready.” – Pamela Berry, Biloxi

For those who endured the power of Katrina firsthand, their stories convey a struggle for survival amidst the overwhelming strength of the hurricane. John Mason of St. Martin, who is proud of his family’s standing as “hurricane veterans,” recalls his experience as the storm surge began to dismantle the home in which he had taken refuge: (Listen to audio.)

The entire structure collapsed under the weight of the roof in probably 15 seconds, in those 15 seconds I can tell you. They had spray-in insulation in there, it looked like it was snowing as I was running for the light. And that is what I told them, I said run for the light. As I was saying that I was thinking about, you know how they always say go toward the light? I was thinking that in my mind, you know like you’re dying. I said run for the light, run for the air. And we ran. And I was telling you earlier about being a blessing and a curse having a life jacket on? The roof split open where we dove through. I dove through, but the girl, the wife, she comes through and the life jacket possibly saved her life. Because the roof came back down with the weight of the wave and it crushed her chest, she had the life jacket on. But the life jacket had her snagged in the roof. She was stuck, and couldn’t get out. So, it was really a hair-raising experience. So about that time another wave come and lifted up the roof, and me and her son, Darryl, pulled Miss Lori through, she scratched her up real bad ‘cause she was wearing nothing but night clothes, no shoes. — John Mason, St. Martin

Aftermath

What becomes almost tangible in the oral histories is the explosive quality of the trauma inflicted by Hurricane Katrina. Echoing through the narratives are the ways in which the foundations of both communities and individuals experienced massive change in such a short span of time.

Elizabeth Brewton, who was too young to have experienced Camille’s destruction, attempts to comprehend the landscape she witnessed post- Katrina:

That was my first real scene of what happened to everything after the hurricane, it was surreal. The pictures on TV didn’t give it justice. I mean, it really did look like somebody had picked up our Gulf Coast, shook us up a little, threw us back down, and stomped all over us. — Elizabeth Brewton, Vancleave

Still reeling from the storm, residents spoke of the agonizing process of sifting through the wreckage. For many, their efforts became a frustrating search for pieces of their life before: (Listen to audio.)

But mostly we just had piles and piles and piles of brick walls and metal, and then you would come upon something like, and it was like, I mean, as bad it was and as ruined as it was, we would get so excited if we found any little thing, you know, that was ours and I would say look this is our sofa sleeper, look at this, look at this, and it would be there and yet there would be; I could see just maybe a shred enough of fabric to know what it was but then it would just be the springs. It looked like a skeleton lying there. It just looked like death. And we would take the shovel and lift up the brick wall and take the rake and rake out from under it you know, and find things and pieces of things, of course. And one of the things that was so incredible to me was there would be stoves and washing machines and pieces of furniture just crumpled into balls. A lot of it you couldn’t really identify, a lot of it you could guess at what it had been. And then like under a pile of broken stuff there would be a piece of blown glass that wasn’t even hurt. — Jan Flowers, Gulfport

Recovery

In the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, many people rushed to respond to the needs of the battered coast. The outflow of humanitarian aid amidst the wake of destruction left by the storm revealed what is best about the human spirit. Forrest County resident Barbara Kay “Babs” Faulk, who served as director of the South Central Mississippi Chapter of the Red Cross during Hurricane Katrina, shares a story about one of the organization’s very special and most memorable volunteers, José:

He slept on a cot right here in my office and took a shower with all the other volunteers staying in the Girl Scout Troop Activity Center, and he worked out in the field in our emergency response vehicles sixteen hours, seven days a week taking food and water and supplies out into the area. And, of course, all the teenage girls fell in love with him because he had this wonderful accent and he was very cute. The thing that was interesting to us is I would answer the phone at 6:30 in the morning and it would be a TV station or a radio station in Spain wanting to talk to José, or a TV station or a newspaper in Germany. So I went, “OK, this is not just your typical kid.” So I said to José, “José, are you special?” —after the twentieth phone call from media in Spain—and he said, “Yes, I’m special. I’m special because I’m a Red Cross volunteer.” And that was the end of the conversation. We later learned that he is from a very prominent Spanish family. But he spent five weeks, got his visa extended, and we had to do all the paperwork to get him back home when it was time so that he could be a Red Cross volunteer, and he ended up on the main web page on our national website.

Along with stories of relief and recovery during the chaotic aftermath of the hurricane come expressions of loss and frustration. Here Faulk speaks to these experiences in her service as a Red Cross director:

We get hate mail every day. If I don’t get cussed out by 8:30 in the morning every day, usually 6:30, I feel like I’m not doing my job. I had to have my phone number at home changed to a private number because I was getting calls at four o’clock in the morning—once I finally got to go home—being cussed out from people that didn’t get what they think they needed. That’s the nature of the beast. I think that every organization probably did a good job. I think we all could’ve done a better job but absolutely nobody from the president’s office in Washington, to the Red Cross office in Hattiesburg, and everybody in-between had ever dealt with anything like this. There’s no way for us to have had the experience or the expertise or the equipment or the supplies or the volunteers or the money or anything else because this was bigger than anything we have ever dealt with. – Barbara Kay “Babs” Faulk, Forrest County

The many components of recovery from Hurricane Katrina are ongoing. Alison Bass, owner of one of Pass Christian’s few remaining homes south of the railroad tracks, remarks on the indomitable spirit that has driven the restoration of her community:

It has really been amazing how quickly, really, things were restored. And I don’t mean back to their original shape. But the thing that you don’t really hear about on a considerable level is the fact that the schools were back by what, September, October, probably. I guess it was October. That people were making do, that people were so tied to that area and determined to make it work. – Alison Bass, Pass Christian

Lessons

Along with the physical destruction of Katrina, many note the deep emotional impact of the storm. Among the people who talk of how their life has changed, one recurring theme is the dramatic shift the event created in their overall sense of values. With their material possessions swept away, residents relate how their perspective has changed: (Listen to audio.)

I mean, I don’t even think about my house and my bed. Honestly, it just doesn’t even cross my mind hardy ever anymore. It is just not important. The things that we used to think were important are so unimportant now. And the things we thought we needed, we don’t need. It’s been such a life-changing experience for us, for everyone. It’s like, we’re getting back to the basics of life. — Jessica Beane, Hattiesburg, volunteering in Bay St. Louis

This sentiment is a common thread that runs through remembered experiences of Mississippians from earlier storms. In an interview from the 1970s, Georgette Torgersen of Waveland realized how Hurricane Camille altered her outlook: (Listen to audio.)

And like so many others have agreed, we all have profited from the destruction of Camille in ways that money cannot buy. It proved that our people in time of great disaster can work together for the good of all. Our whole way of life has changed, material things aren’t so important any more. Nearly everything can be replaced in time. And my greatest loss were our children’s pictures. It has given me a feeling of never wanting to own anything that owns me again. — Georgette Torgersen, Waveland

Telling and retelling the stories

Oral histories have allowed and encouraged participants to reflect on their personal experiences with Katrina. Sociologist Arthur Neal, who has studied reactions to the national traumas of the 20th century, such as the Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor in 1941 and the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962, argues the importance of the process of reflection for recovery. Neal maintains that “reflection is required in order for an extraordinary event to be understood and made coherent.” It is in remembering and telling these stories that help individuals make sense of, and draw meaning from, the event. Wendy Frost, a nurse who was a first responder to the coast, describes the importance of remembering these stories: (Listen to audio.)

What really struck me I think on my first day when I got there was the sense by the people that they had been forgotten. And, um, they were forgotten, even before the hurricane hit. And the one thing that I promised them – I always kept my promises, if I said I was going to bring them something I brought it the next day. The one thing that I promised them, and I promised every single one of them that I met was that they would never be forgotten again. Somebody asked me what I was going to take from this experience and even though these people have nothing to give, they have given me a lot. And the one thing that I am gonna take from here is their stories. And I am going to tell their stories and I promised them, every one of them, that they will never be forgotten again. And I won’t forget them, and I will make sure other people don’t forget them. — Wendy Frost, volunteer nurse from Finley, Ohio, working in Pearlington.

Looking back allows the people of South Mississippi, individually and collectively, to appreciate and embrace their roots as they head into a period of rapid reorganization and rebuilding.2 Amid the devastation of coastal Mississippi, most residents remain shaken, but deeply rooted in the place they still call home.

Stephen Sloan, Ph.D., previously assistant professor of history and co-director of The Center for Oral History and Cultural Heritage at the University of Southern Mississippi, joined Baylor University in August 2007 as director of The Institute for Oral History and assistant professor in the history department.

Endnotes:

1 The National Hurricane Center recorded three landfalls for Hurricane Katrina, first on the southeastern coast of Florida as a Category One hurricane on August 25 where it crossed the peninsula to enter the Gulf of Mexico on August 26. Over the warm waters of the Gulf, it strengthened to a Category Five hurricane before it weakened to a Category Three at its first Gulf landfall at Buras, Louisiana, on August 29 at 6:10 a.m., Central Daylight Savings Time. Katrina passed over the narrow Louisiana peninsula that juts out south of coastal Mississippi and continued northward. Katrina made its third and final landfall around 10:00 a.m. near the mouth of the Pearl River still as a Category Three.

2 The Governor’s Office of Recovery and Renewal reports in its Mississippi Recovery Fact Sheet that as of June 12, 2006, individual applications for assistance from the three coastal counties (Hancock, Harrison, and Jackson) has reached 193,951 with a total of $914,482,228 in approved funds.

-

General destruction caused by Hurricane Katrina in Biloxi, Mississippi. Photograph by Linda VanZandt. Courtesy The Center for Oral History and Cultural Heritage, University of Southern Mississippi. -

Damage to a historic home on U.S. 90, the beach highway. Photograph by Linda VanZandt. Courtesy The Center for Oral History and Cultural Heritage, University of Southern Mississippi.

-

Supplies are distributed in post-storm relief efforts at the Church of the Vietnamese Martyrs, Biloxi. Photograph by Linda VanZandt. Courtesy The Center for Oral History and Cultural Heritage, University of Southern Mississippi. -

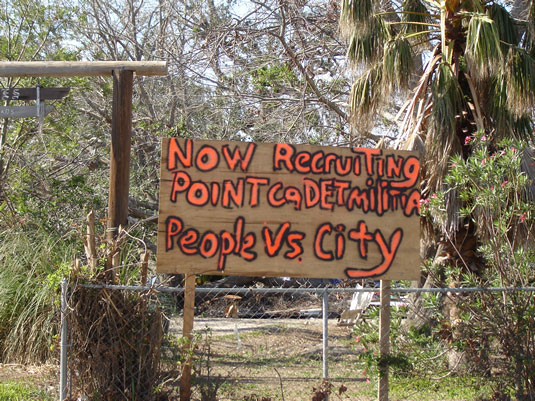

Citizens in the Point Cadet community of Biloxi express their frustration with public officials after the storm. Photograph by Linda VanZandt. Courtesy The Center for Oral History and Cultural Heritage, University of Southern Mississippi. -

Public forum for citizens in Waveland, Mississippi, after Katrina flattened the small coastal town. Photograph by Linda VanZandt. Courtesy The Center for Oral History and Cultural Heritage, University of Southern Mississippi.

Sources:

Mississippi Official and Statistical Register, 2004-2008, pp. 678-680

National Hurricane Center, Tropical Cyclone Report, Hurricane Katrina, August 23-30, 2005, prepared by Richard D. Knabb, Jamie R. Rhome, and Daniel P. Brown, December 20, 2005.

(Click on Hurricane Katrina at http://www.nhc.noaa.gov/ 2005atlan.shtml) – accessed July 2006

University of Southern Mississippi’s Center for Oral History and Cultural Heritage http://www.usm.edu/oralhistory/ – accessed July 2006