Mississippian Ellen Sullivan Woodward went to Washington in August 1933 to be the federal director of work relief for women, a job that was considered to be the second most important to which President Franklin Roosevelt appointed a woman. Only Secretary of Labor Frances Perkins ranked higher.

Woodward would work in the nation’s capital for the next 20 years. Economic security for women would remain her focus when she became a member of the Social Security Board in 1938 and beyond, when, after World War II, she directed a division of the Federal Security Agency.

Woodward was born in Oxford, Mississippi, in 1887. After her marriage in 1906 to Albert Y. Woodward, she lived in Louisville. She was active in community work and at her husband’s death in 1925, she was elected to complete his term in the Mississippi House of Representatives and was the second woman to serve there. (Nellie Nugent Somerville was the state’s first woman representative.)

In 1927, Woodward was in Jackson where she held administrative posts in the Mississippi State Board of Development, a private-sector organization intended to promote business in Mississippi and with Mississippians. National welfare leaders from Washington admired her work toward better homes, community beautification, public health, libraries, parks and playgrounds. That is how she came to the attention of the men who were creating projects in 1933 to put to work unemployed men and women who could find no jobs after the Great Depression was underway.

The Women’s Division

The country’s first lady, Eleanor Roosevelt, was one of the first persons to support the idea that there should be a women’s division in the new Federal Emergency Relief Administration (FERA). She sponsored a White House Conference on the Emergency Needs of Women in November 1933. That was when Woodward first described the projects her new division had developed since August under the FERA that already had women on jobs in many states.

For a time, over that hard winter of 1933-1934, there was another work program called the Civil Works Administration (CWA) that included women. By the end of 1933, nationwide, about 300,000 needy women were at work on CWA jobs. Then in 1935 a new and much larger work program was created, the Works Progress Administration (WPA) and at its peak in 1936 there were about a half million women on what were called “made work” jobs that were categorized as “socially useful.”

Mississippi women at work

Woodward was especially anxious that women in her home state have access to work relief jobs. Almost every kind of project that was developed to put women to work existed in Mississippi. In fact, under Ethel Payne, the state director of women’s work, Mississippi had some projects that were “showcases” for the nation. One of them was the Library Project.

Today most of the town and county libraries in the state began as FERA or WPA libraries. An American Library Association official wrote that “what is being done in Mississippi is likely to be one of the most significant projects that has taken place.” Another aspect of the Library Project was Braille transcription that operated in fifty-one Mississippi counties in 1939 to employ blind persons who produced mostly children’s literature.

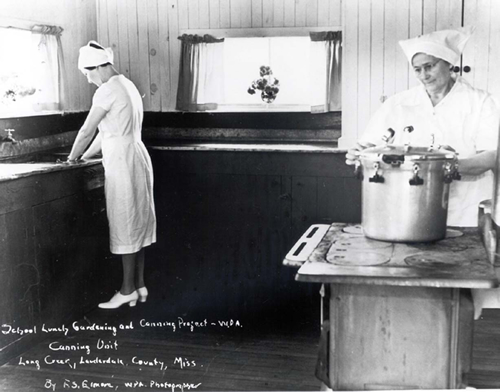

Women also worked in gardening and canning during the summers and then ran school lunchrooms during the school year, another “first” in many areas. By 1939 the lunch program fed an average of 46,000 children every school day. Needy families benefited from the clothing, household goods, and mattresses that were made on the Clothing and Production Projects.

In Mississippi, as elsewhere, more women were put to work on Sewing Projects than in any other endeavor. Prior to the Christmas season they used scrap materials to make toys for “Santa’s helpers” and for lending to children from “Toybraries.” Goods produced by sewing rooms were rushed in great quantity to Tupelo after the tornado in 1936 and to the Delta after floods in 1937. By 1940 WPA sewing rooms had produced over 4,000,000 garments for distribution to needy families in the state.

Women received work relief jobs on many other kinds of projects. They brought parks and recreation programs to many towns that had never had them. Many of today’s county health departments had their first real beginnings with nurses on WPA jobs. Hattiesburg had the only free health clinic for children in the state. WPA women sponsored nursery schools, principally for children of women at work on other work projects. In 1938 more than a thousand women were employed as housekeepers to serve relief families where illness or other emergencies called for household assistance.

Three historical projects that employed men and women left a legacy of inestimable value: The WPA workers wrote separate histories of every county in the state; they surveyed and inventoried historical records; and they located federal archival material scattered about the state.

The Professional Projects

In 1936 Woodward’s position became that of Director of the Women’s and Professional Projects when she was given authority over projects that employed out-of-work actors, writers, musicians, and artists. Mississippi did not have a Theatre Project, but it had the other three.

The only racially integrated professional projects was the Federal Music Project that hired Black music teachers. Some women played in the Jackson Orchestra that gave 312 concerts from 1935 to 1937. Under (Miss) Jerome Sage, the Music Project workers offered free music lessons to adults and children and won acclaim as one of the exemplary projects in the nation. It operated in forty counties and reached 69,640 students in 1936. William McDonald wrote that “the spirit of school children in Mississippi who traveled long distances without breakfast to study music . . . was more important, not only socially and politically . . . than an exhibition of WPA art in the New York Museum of Modern Art.”

The Greenville writer, William Alexander Percy, helped established the Delta Art Center. The Oxford Art Center was located at the Mary Buie Museum. Numerous children and adults received free art lessons during the life of the projects, directed in Mississippi first by Delta artist Caroline Compton and then by the sculptor Leon Koury. The Federal Art Project, in particular, brought art education and art exhibits to basically rural counties.

The Federal Writers’ Projects under Eri Douglas produced a number of publications that preserved Mississippi folklore. Its most notable work was the still consulted and reissued Mississippi: The WPA Guide to the Magnolia State (1938). The project hired a reporter and photographer named Eudora Welty.

The numbers

The number of women employed on WPA jobs fluctuated and pay scales were based on the type of work. A report for July 1937, however, can be cited. It showed that in Mississippi 32.7 percent of WPA employees were women while the average for the nation was 18.2 percent. The average wage was 31 cents an hour. That may seem very low today but it was close to a “living wage” at that time. In the 1937 book You Have Seen Their Faces by Erskine Caldwell and Margaret Bourke-White, a White sharecropper at Liberty is quoted: “Last year my wife . . . got herself a job with the government, and now she’s making twenty-one dollars a month working at the sewing house. That just about takes care of everything.”

The problems

All the women’s projects had to be submitted to the man who was the FERA and WPA chief officer and he often allocated funds and gave his approval to construction projects that employed more men. Men officials too often could not accept the idea that many families could look only to women for support. Too, there was much local prejudice against projects set up for Black women who headed families. Built into the WPA law was a provision that the federal government would provide money for wages and very little else. “Sponsors,” such as civic clubs, were expected to pay for the rent and utilities of work sites and provide materials such as the library books. This worked a hardship on Black workers because even when their projects could receive sponsorship, the resources were paltry. Of all southern states, Mississippi had the lowest proportion, at 18.5 percent, of the total employees who were Black on WPA projects. In 1938, for example, only 709 Black females held WPA jobs.

Women’s work goes to war

In December 1938 Ellen Woodward resigned from the WPA and became one of three members of the Social Security Board. Under Florence Kerr from Iowa, her successor at the Women’s and Professional Projects, almost all of the project work continued, but after defense preparations began in 1940 for the approaching war, many of the projects in Mississippi were adapted to serve new aims. Libraries and recreation programs were created for bases such as Camp Shelby and Keesler Field. The education programs concentrated on teaching illiterate draftees; clerical workers assisted agencies such as the Office of Civilian Defense; art classes made defense posters. In short, by 1942 the WPA had gone to war. By 1943 all of the projects had been liquidated because workers left for the armed services or jobs in private industry.

The legacy

Many of the women’s work projects produced goods and provided services that were so much needed and so much appreciated by their communities that they were continued as vital to the welfare of the people. Even when some were dropped, they reappeared as parts of President Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society programs in the 1960s and they are still with us today – in school lunches, home health care, nursery schools for low-income groups, historic preservation, and delivery systems for social services. There are important antecedents for all of these in the work of the Women’s and Professional Projects of the New Deal.

Martha H. Swain is Cornaro Professor of History emerita at Texas Women’s University. She is co-editor of Mississippi Women: Their Histories, Their Lives, and the author of Ellen S. Woodward: New Deal Advocate for Women and Pat Harrison: The New Deal Years.

-

Ellen Woodward, right, with First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, 1938. Courtesy, National Archives. -

WPA Sewing Room in Jackson, Mississippi. Courtesy, Mississippi Department of Archives and History.

-

WPA Library in Hancock County, Mississippi. Courtesy, National Archives. -

WPA Day Nursery in Bay St. Louis, Mississippi, 1936. Courtesy, National Archives. -

WPA Gardening and Canning Project in Lauderdale County, Mississippi. Courtesy, Mississippi Department of Archives and History. -

WPA Toy Lending Project in Jackson, Mississippi. Courtesy, Mississippi Department of Archives and History. -

WPA Music Project in Guntown, Mississippi. Courtesy, Mississippi Department of Archives and History.

Selected bibliography

Douglas, Eri. “The Federal Writers’ Project in Mississippi, Journal of Mississippi History, vol. 1 (1939), 71-76.

Krause, Bonnie J. “The Mary Buie Museum, Oxford, Mississippi, as a WPA Community Art Center, 1939-1942,” Journal of Mississippi History, vol. 60 (1998), 141-54.

McDonald, William F. Federal Relief Administration and the Arts. Athens; Ohio State University Press, 1969.

“Progress Report, WPA Library Extension Project,” Mississippi Library News, vol. 5 (1941), 9-10.

Rainwater, Percy L. “The Historical Records Survey in Mississippi,” Journal of Mississippi History, vol. 1 (1939).

Rossell, Beatrice S. “New Book Services for Rural Areas, Rural America, vol. 12 (1934), 3-6.

Schilling, George. “The Survey of Federal Archives in Mississippi, Journal of Mississippi History, vol. 1 (1939), 207-16.

Swain, Martha H. Ellen S. Woodward: New Deal Advocate for Women. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1995.

Swain, Martha H. “A New Deal for Mississippi Women,” Journal of Mississippi History, vol. 46 (1984), 191-212.

Ellen Woodward Papers. Mississippi Department of Archives and History (Jackson).