Aaron Henry was born in 1922 in Coahoma County, Mississippi, the son of sharecroppers. From a young age, he worked in the cotton fields alongside his family on the Flowers Plantation outside of Clarksdale. He remembered those years vividly when he recalled, “As far back as I can remember, I have detested everything about growing cotton.” Regardless of his early hardships, education was a priority for the Henry family.

After graduating from the all-Black Coahoma County Agricultural High School in 1941, Henry worked as a night clerk at a motel, The Cotton Boll Courts, to earn money for college. He was drafted into the United States Army in 1943, and trained with the 381st Infantry Division at Fort McClellan in Alabama. He served as a staff sergeant in the Pacific Theater during World War II, but like most other African American soldiers, he experienced the segregated practices of the military. He decided then that when he returned home to Mississippi after the war, he would work to gain equality and justice for Black Americans.

Clarksdale businessman

Henry worked at various jobs after the war, and then used the G. I. Bill, a law that provided educational benefits for World War II veterans, to attend Xavier College (now Xavier University) in New Orleans. Graduating in 1950 with a pharmaceutical degree, he returned to Clarksdale and opened the Fourth Street Drug Store along with K. W. Walker, a White Mississippian. It was the only Black-owned drugstore in the area. As Henry recalled, “Our drugstore was to become the gathering place and the hub for political and civil rights planning for three decades.” During this same period, he married Noelle Michael. They had one daughter and named her Rebecca.

As a businessman in Clarksdale, Henry became involved in local and state activities, particularly events such as African American voter registration. He worked with Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and accepted a position on the Southern Christian Leadership Conference board. Henry organized the local branch of the National Association of the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and in 1959, was elected president of the Mississippi organization. He would serve in the NAACP for decades, yet was open to any plan that would help expand justice and political and economic rights for Black Mississippians.

He became best friends with another Mississippian who was working for the same goals, Medgar Evers, field secretary for the NAACP. On June 12, 1963, however, Evers was assassinated in his driveway in Jackson, Mississippi. The assassination of Evers had a great impact on Henry.

Freedom vote campaign

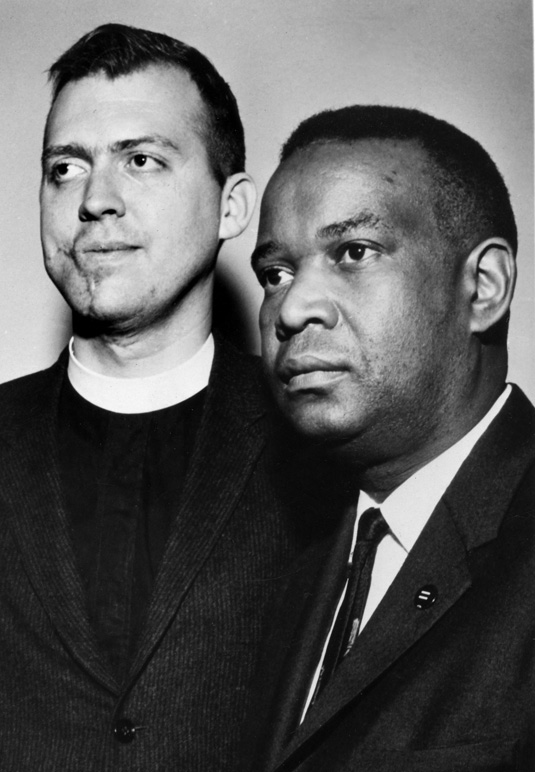

Henry worked with other forces and groups to establish the statewide Council of Federated Organizations (COFO). He served as president of COFO in 1962 and helped organize the “freedom vote,” a mock statewide general election to parallel the Mississippi gubernatorial election of 1963. Henry believed that if African American voters showed their willingness to vote in this mock election, then Mississippians and the nation would realize that Black voters would participate in the electoral process. Henry was on the mock ballot for governor and Edwin King, a White chaplain at Tougaloo College in Jackson, was on the ballot for lieutenant governor. In addition to the freedom candidates, the mock ballot included Democratic candidate Paul B. Johnson Jr. and Republican candidate Rubel Phillips. Ballot boxes were placed in churches, businesses, and homes across the state, and voting took place over a weekend, from Friday to Monday. Henry and King “won” the mock election in which more than 80,000 Black Mississippians voted. This event showed the country that African Americans would vote if given the chance.

An incident during the freedom vote campaign prompted Henry to become involved in challenging the re-licensing of the major Jackson television station, WLBT, in the 1960s. The station had a history of anti-Black programming and policy, and when Henry and Dr. R.L.T. Smith went to the television station to purchase airtime, the station manager told them that “niggers couldn’t buy time.” Henry and colleagues then initiated a successful legal challenge to remove the station’s license. As a result of his actions, more African American news anchors and employees came on board at television stations across the nation. Henry was elected chairman of the WLBT board of directors in December 1979.

During the summer of 1964, known as Freedom Summer, students from across the United States journeyed to Mississippi to join COFO workers and local people in organizing voter registration, developing freedom schools, and creating grass-roots efforts. Working out of his Fourth Street Drug Store, Henry welcomed the young activists and offered them a Coca-Cola and encouragement as they registered voters throughout the Delta region.

Three of these workers, James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner disappeared in Neshoba County. Six weeks later, their bodies were discovered. Goodman and Schwerner were White, and Chaney was Black. The murder of the three young men spurred Henry on with his efforts at voter registration.

Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party

Henry also helped create the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP) to address concerns about civil rights in Mississippi. During the 1964 U. S. presidential election, Henry and other civil rights leaders decided it was time to challenge the seating of an all-white Mississippi delegation headed to the Democratic National Convention in Atlantic City, New Jersey. Meeting in Jackson on August 6, 1964, the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party proceeded to form a delegation from the state to be seated at the convention. Black leaders felt that the national Democrats would, at minimum, offer delegates some at-large seats or votes in determining who would represent the Democratic Party in the upcoming presidential election. After much strife, demonstrating, and continual meetings with Democratic Party leaders, Lyndon B. Johnson and Hubert Humphrey, the “official” Democratic Party then offered two at-large seats to Reverend Edwin King and Aaron Henry. The MFDP delegates were frustrated at what had happened after all of their work and high hopes. Fannie Lou Hamer, a Mississippian involved in the MFDP and other organizations, publicly expressed her criticism of only receiving two at-large seats. Henry, however, believed that the MFDP had done its best and had “learned a great deal about the way things work up in the world of high-level politics—heartbreak and all.” He was determined to continue his work.

With much criticism from other Mississippi activists, Aaron Henry remained faithful in his loyalty to the national Democratic Party, and worked actively at following national party conventions in the following years. President Jimmy Carter, in recognizing Henry’s devotion to the party said, “Aaron Henry was a civil rights hero whom I knew best for his tenacity in breaking through racial discrimination and making sure that African American Democrats had a voice in party politics in Mississippi and in the nation.”

Mississippi legislator

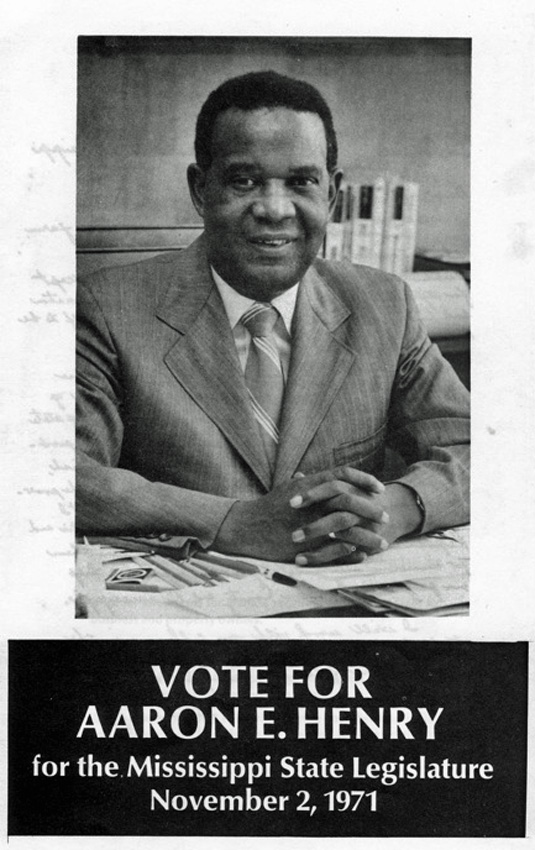

Henry was elected to the Mississippi House of Representatives in 1979 and served in that capacity until 1996. Although he was not a legislator who called attention to himself, he was active on the Ways and Means Committee, fighting for measures that boosted housing, education, health care, and employment opportunities for African Americans. He worked with other legislators so that they could understand the historical importance of any laws that would have an impact on Black communities across Mississippi. At the beginning of the 1988 legislative session, Henry introduced a bill that the Confederate battle flag be removed from the canton of the Mississippi state flag. The bill was never brought to the floor for a vote, nor were any of the others he introduced in 1990, 1992, and 1993.

After a long career fighting for civil rights and with declining health, Henry lost his re-election campaign to the Mississippi Legislature in 1995. He never recovered from a 1996 stroke and died in May 1997.

Aaron Henry’s legacy

Henry once said that his grandmother had inspired him to become involved in the struggle for civil rights. She told him he was just as worthy of justice as any White man and that “they put on their pants the same way you do, one leg at a time.”

Historians such as John Dittmer recognize the role Henry played in the Civil Rights Movement in Mississippi. Dittmer described Henry “as a link between black middle-class Mississippians and the younger full-time activists in SNCC [Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee] and CORE [Congress for Racial Equality].” This was particularly true in the years 1961 through 1965. Dittmer added, “That he [Henry] stayed in Mississippi, and for the next three decades fought for human rights in a different political environment is a tribute both to his commitment and to his under-appreciated role as Mississippi’s most important black politician since Reconstruction.” During his fight for civil rights, Henry was arrested more than thirty times, his home was firebombed, and his pharmacy was both vandalized and firebombed.

Aaron McClinton, Henry’s older grandson, described his experiences at his grandfather’s drugstore, recalling that he saw photographs of Martin Luther King Jr., John and Robert Kennedy, murdered civil rights workers Chaney, Schwerner and Goodman, and others displayed on the wall behind the ice cream counter. Remembering his grandfather’s words, McClinton said, “I never will forget—my grandfather told me that they were killed so I could vote.”

Constance Curry is a fellow in women studies at Emory University. She was a member of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee executive committee from 1960 to 1964. She has written, or collaborated in, five books on people with whom she worked in the freedom movement.

-

Aaron Henry's Fourth Street Drug Store, which opened in 1950 in Clarksdale, became a hub for political and civil rights planning for three decades. Aaron Henry Papers, Mississippi Department of Archives and History, 90.24, Box 144, Folder 4. -

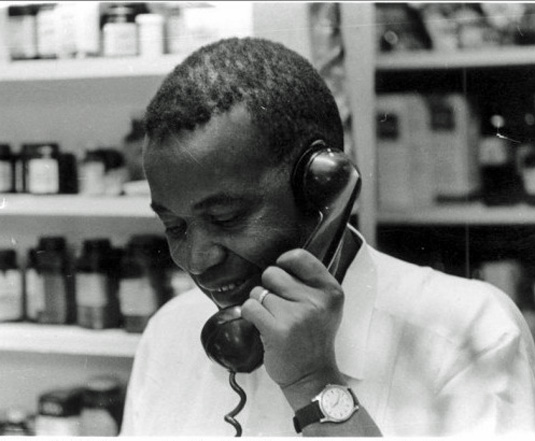

Aaron Henry inside his pharmacy in 1964. Photograph from the Margaret J. Hazelton Freedom Summer Collection, McCain Library and Archives, The University of Southern Mississippi.

-

Noelle Michael Henry, wife of Aaron Henry, in 1964. Photograph from the Margaret J. Hazelton Freedom Summer Collection, McCain Library and Archives, The University of Southern Mississippi. -

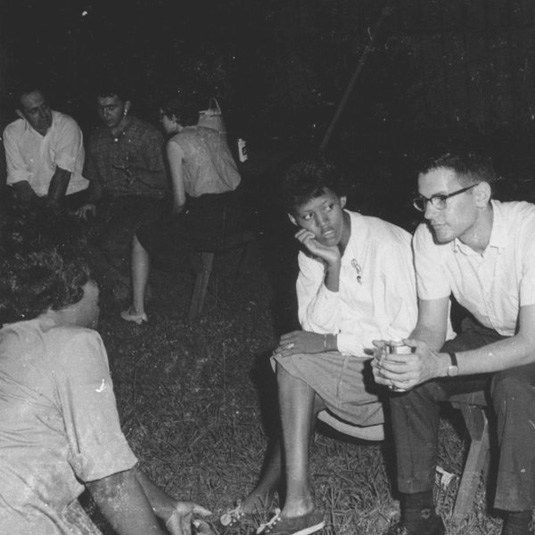

A gathering of voter registration volunteers in Henry's backyard during Freedom Summer, 1964. Photograph from the Margaret J. Hazelton Freedom Summer Collection, McCain Library and Archives, The University of Southern Mississippi. -

Edwin King and Aaron Henry. During Mississippi's 1963 gubernatorial election, COFO organized a mock election to show the potential strength of the black vote. Aaron Henry was on the mock ballot for governor, and Edwin King, chaplain at Tougaloo College, was on the ballot for lieutenant governor. Photograph courtesy Tougaloo College Archives. -

Aaron Henry, chair of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party delegation, speaks before the Credentials Committee at the Democratic National Convention in Atlantic City, New Jersey, August 1964. Photograph courtesy Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, LC-U9-12470E-28. -

Brochure from Henry's 1971 campaign. In 1979 he was elected to the Mississippi House of Representatives and served until 1996. Aaron Henry Papers, Mississippi Department of Archives and History, 90.24, Box 144, Folder 1. -

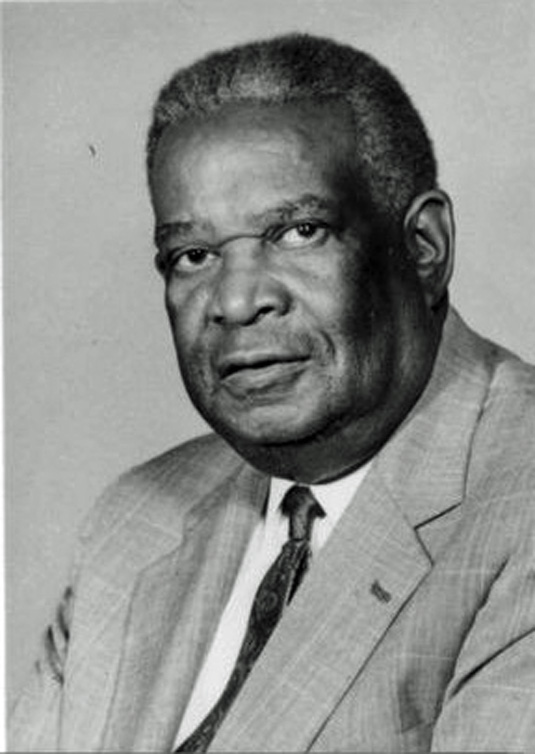

Aaron Henry, circa 1980s. Photograph from the Erle E. Johnston Jr. Papers, McCain Library and Archives, The University of Southern Mississippi.

Reference:

Henry, Aaron, with Constance Curry. Aaron Henry: The Fire Ever Burning. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2000.

Sansing, David. Flags Over Mississippi, Mississippi History Now (August 2000).