In 2015, the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) designated Mississippi State University (MSU) as host of the National Center of Excellence for Unmanned Aircraft Systems. The “unmanned aircraft” at the center of this study are more commonly referred to as “drones.” As a part of its charge, the FAA not only tasked MSU with pioneering mechanical advances in drone technology, but it also instructed the university to review existing laws, policies, and regulations associated with the new aerial machines and to recommend needed changes. The FAA announced that it had selected MSU for several reasons, including the university’s expertise in a variety of engineering fields, its proximity to corporations conducting similar research, and MSU’s longstanding relationship with both the FAA and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA). The choice of MSU, however, was fitting for another reason that was not cited in the FAA’s initial press release announcing its selection. MSU’s connection with legal aviation began a century ago through one of the university’s first graduates, Blewett Harrison Lee.

Blewett’s Early Life

Blewett Lee was a remarkably creative attorney whose breadth of interests and force of opinion led to his being one of the most important legal authorities in Mississippi history. Although his rightful place in the annals of aviation law has been largely overlooked, Lee played an integral part in the development of some of the original laws pertaining to the operation of early “flying machines.” In many ways, Blewett’s career and influence in the field of aviation law mirrors the tandem advance of both law and technology across the nation during the twentieth century.

Blewett was born on March 1, 1867, in Columbus, Mississippi, to Regina Harrison Lee, the daughter of a prominent Mississippi family, and her husband, former Confederate Lieutenant General Stephen Dill Lee. When Blewett was born, Regina Lee’s father wrote the following about his newborn grandson: “Poor little thing, it little knew what a world it was coming into, or the prospects in the future. . . .” At the time of Blewett’s birth, many citizens of Columbus, like the rest of the South, continued to suffer mightily in the wake of the American Civil War, but Blewett’s birth helped General Lee to “enjoy peace of mind” during this desperate time. He also began renovating his wife’s family plantation in Columbus after the war. The family’s future, however, began to truly change in 1879 when Governor John M. Stone appointed General Lee to be the first president of Mississippi Agricultural and Mechanical College (Mississippi A&M, now MSU). In 1880, General Lee took over a small, flailing menagerie of students, faculty, and structures, but by the time of his retirement in 1899, he had helped build the fledgling institution into a regional leader in research and education. During General Lee’s tenure as president, the university also became the intellectual setting within which his son, Blewett, developed the foundation of his future career path.

Blewett’s Educational and Professional Path

By the time Blewett enrolled in the early 1880s, the university under his father’s leadership had adopted a new focus on agricultural training and applied sciences, which meant that Blewett and his classmates underwent a relatively rigorous course of practical training (i.e. laboring on the school’s farms), as well as a full load of traditional classroom education, including chemical physics, entomology, rhetoric, and history. The university’s focus on applied sciences had a profound effect upon Blewett’s continued education and his future legal career. After receiving a second degree from the University of Virginia, the South’s leading academic institution at the time, Blewett earned his law degree from Harvard Law School in 1888 at the age of twenty-one. While at Harvard, he impressed members of the faculty as well as fellow classmates. Samuel Williston, a classmate of Blewett and later dean of Harvard Law School, said the following about him: “His brilliant mind, geniality, simplicity, and an outlook somewhat colored by his Southern training made him an attractive companion.” Following Harvard, Blewett studied at universities in Freiburg and Leipriz, Germany.

In 1889, Blewett began the most important and transformative phase of his professional life when he served as a legal assistant—what we now call a “clerk”—for United States Supreme Court Associate Justice Horace Gray. This appointment was a great accomplishment for the young lawyer who at the time was very much an outsider in Washington. He was the only clerk not to have attended an elite preparatory school, the only one not a graduate of Harvard College, and the only law clerk from south of the Mason-Dixon Line. In 1893, Blewett moved to Chicago where he taught law at both Northwestern University and the University of Chicago and also served as chief legal counsel for the Illinois Central Railroad, one of the most powerful corporations in the nation at the time. In 1898, thirty-year-old Blewett married Frances Glessner, a wealthy Chicago socialite. Early in their marriage, the couple moved to Atlanta where Blewett began a private law practice. The couple had three children but eventually divorced in 1914. (Interestingly, Frances went on to pursue her own notable career as an early pioneer of forensic science, known mainly for her precise dioramas depicting crime scenes.) Despite his prominence as an attorney within the railroad industry, Blewett’s greatest accomplishments were achieved within the field of an entirely different and brand new form of transportation: aviation.

Blewett’s Influence Upon Early Aviation Law

Blewett approached the law from two seemingly contradictory perspectives: a global view, on the one hand, and a very narrow, detailed view on the other. Much of this approach to the law can be attributed to his undergraduate education at Mississippi A&M and its emphasis on applied sciences. Blewett once told an audience at Harvard Law School that “the law is a science, therefore its conclusions have universal validity.” Both lawyers and judges, he argued, should approach legal issues methodically and empirically in the same manner as a chemist would approach a laboratory experiment. He also believed that in order to understand aviation law one must first understand the science of flight.

Although aerial transportation was in its infancy as Blewett began his legal career, he saw the potential that air travel offered. He was one of the first lawyers to recognize that the legal issues surrounding rail travel had the potential to hinder the advance of aviation. He understood that the laws governing machines moving on steel rails could not simply be applied to machines moving through the sky. In early 1913, a mere ten years after the Wright Brothers’ first flight, Blewett published his legal musings on the ramifications of aircraft technology in the American Journal of International Law. In his article, “Sovereignty of the Air,” Blewett pointed to existing European aviation laws and called upon the American legal system to prepare for the new realities of air travel. At the time, Massachusetts and Connecticut were the only states that had enacted any aviation laws. Referencing a Connecticut law that required all pilots to hold an operator’s license, Blewett wrote: “When aeroplanes become as plentiful as blackberries, Connecticut will be found prepared.” Massachusetts aviation law went a step further than that of Connecticut by imposing altitude requirements for any aircraft flying over municipalities or “crowds of people” and by holding aviators responsible for any damages caused by their flights.

Blewett worked to extend aviation laws in the United States. His policy initiatives helped to determine who would be allowed to pilot early flying machines, where these machines would be allowed to fly, and what activities or maneuvers these aircraft could perform while airborne. Blewett’s ideas and methodology concerning aerial laws, published nearly a century earlier, remain influential today. In a 2012 article referencing the legal issues posed by the popularity of drones, Dr. Timothy T. Takahashi of Arizona State University cited Blewett’s work as a viable model for current drone regulations. According to Takahashi, the relevance of Blewett’s work (ironically now the work of MSU itself by virtue of the FAA’s appointment), is in marked contrast to the failure of existing federal aviation law to “provide a durable framework to welcome the ‘arrival of the drones’.”

Blewett’s Effect on Spiritualism

Blewett’s legal interest and sphere of influence did not lie solely within the field of transportation. Essentially, he was also a pioneer in a much stranger corner of the legal world, spiritualism, the belief that departed spirits interact with mortals. Through a series of articles with such suggestive titles as “Spiritualism and Crime,” “Psychic Phenomenon and the Law,” and “The Conjurer,” Blewett became the leading American legal thinker on spirits. Just as Sir Isaac Newton’s mastery of science led him to a fascination with the “mystical pursuit” of alchemy, Blewett’s expanding legal career similarly directed him toward “mystical pursuits” within the realm of jurisprudence.

Blewett’s foray into such “mystical pursuits” in the legal system is perhaps even more pioneering than his observations about the laws of aviation. In a 1923 article published in the Virginia Law Review under the title, “The Fortune Teller,” Blewett compared the lawyer’s role to that of a soothsayer. “All of us,” he argued, “predict the future more or less . . . [and] such predictions as these are based on science or experience; they rest on the laws or uniformities of nature, including human nature, and are successful in so far as these laws are known and intelligently applied.” From Blewett’s standpoint, the more one understands the laws of nature, the better one can predict the future. “The main difficulty about psychic phenomena,” Blewett once argued, “is not with the law, but with the facts, and what is worse, the explanation of them. The law we have already.” Ultimately, he suggested that the field of law, and perhaps the field of medicine as well, needed to consider the mind itself more deeply and that there might be more science than religion behind the work of mediums. Furthermore, Blewett believed that mediums, soothsayers, and spiritualists should be afforded deeper understanding by the legal system, rather than being routinely and summarily judged as witches or shams. From his childhood in post-Civil War Columbus to his early education at Mississippi A&M, Blewett stood out as a bright, engaged person whose mind perhaps worked a bit differently than most others. Due to his unconventional legal interests and the fact that his perception of the world was slightly askew from that of his peers, Blewett, who managed to help shape the legal landscape of the twentieth century, has been relegated to the shadows of his father’s wartime service and popularity. Even in death, Blewett remained in his father’s shadow. He died in Georgia in 1951 at the age of eighty-four but was buried in Friendship Cemetery in Columbus along with his father and mother. However, Blewett Harrison Lee rightly deserves to be remembered in his own right for his innovative legal thinking, his seminal contributions to the revolutionary field of aviation law as well as spiritualism, and as having possessed one of the greatest legal minds in Mississippi history.

Whit Waide is a clinical assistant professor of political science, university pre-law advisor, and general counsel to students at Mississippi State University.

James C. Giesen is an associate professor of history at Mississippi State University. He also serves as executive secretary of the Agricultural History Society and series editor of the Environmental History and the American South Series published by the University of Georgia Press.

Other Mississippi History NOW articles featuring lesser-known, but influential Mississippians:

Sarah Anne Ellis Dorsey: A Woman of Uncommon Mind

Isaiah T. Montgomery, 1847-1924 (Part I)

Isaiah T. Montgomery, 1847-1924 (Part II)

-

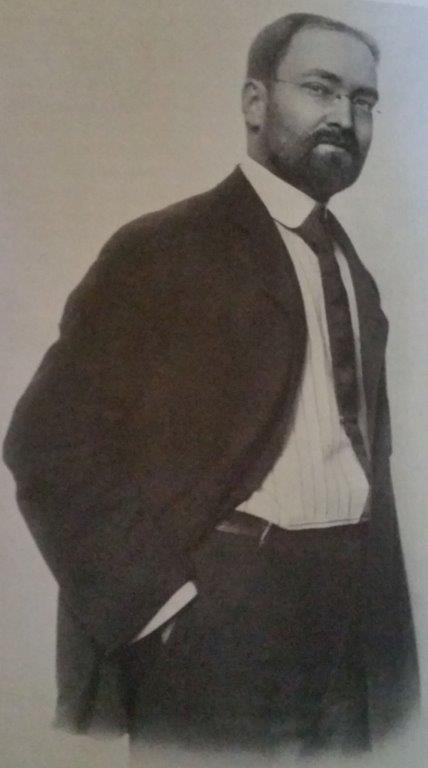

Photograph of Blewett Lee circa 1905. Courtesy of the Stephen D. Lee Home and Museum, Columbus, Mississippi. -

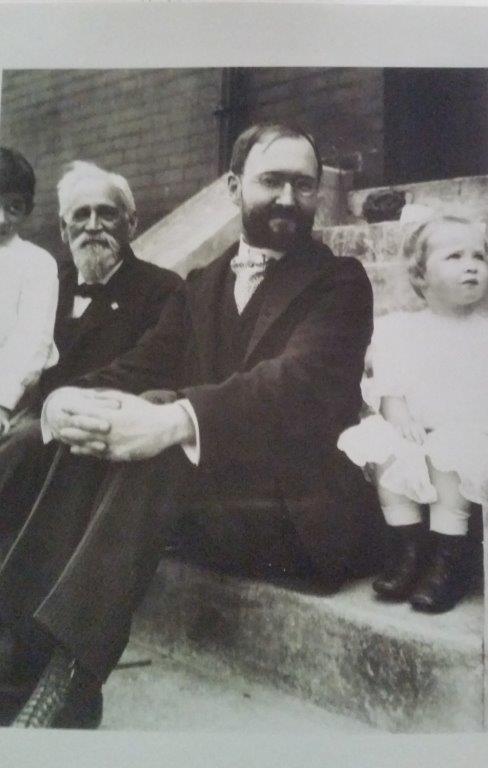

Photograph of General Stephen D. Lee, Blewett Lee, and Blewett’s daughter, Frances Lee, taken in Chicago in 1905. Blewett’s son, John Glessner Lee, is partially seen in the left of the photograph. Courtesy of the Stephen D. Lee Home and Museum, Columbus, Mississippi.

-

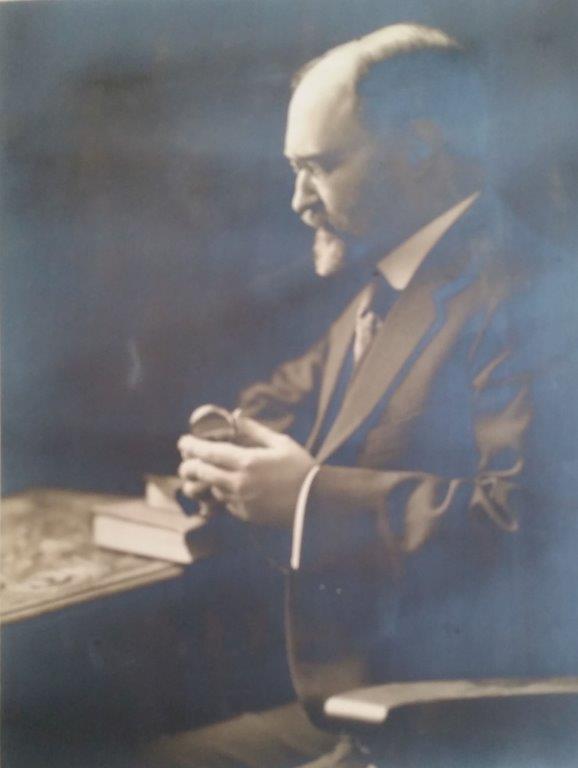

Studio photograph of Blewett Lee taken later in his life. Courtesy of the Stephen D. Lee Home and Museum, Columbus, Mississippi. -

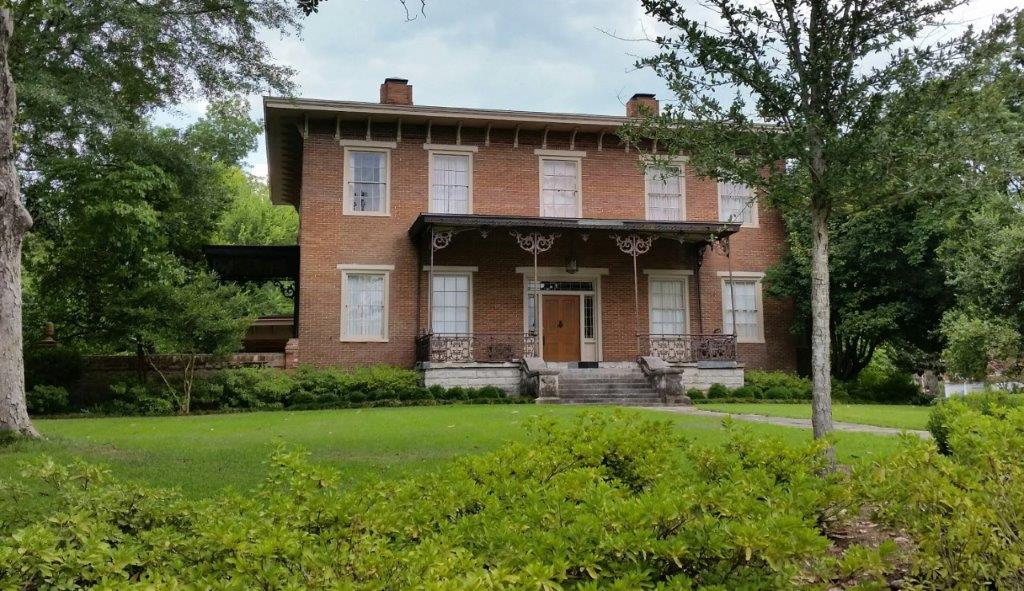

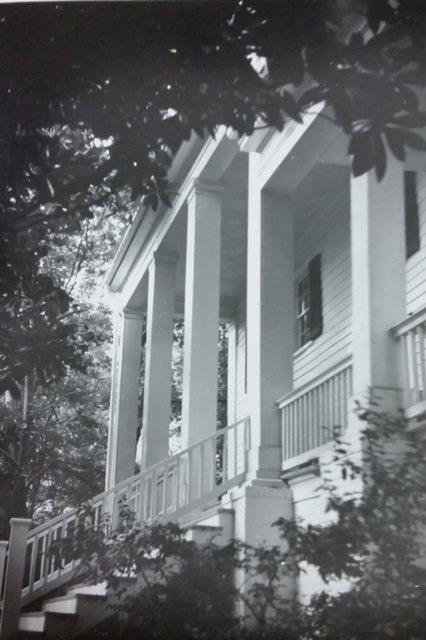

Photograph of the James T. Harrison Home in Columbus, Mississippi. The home was built circa 1840 by Thomas Blewett for daughter Regina and James Harrison. It was the site of the 1865 marriage of Stephen D. Lee and Regina Harrison Lee and the childhood home of Blewett Lee. Courtesy of Carolyn Burns Kaye of Columbus, Mississippi. -

Photograph of the Hickory Sticks property in Columbus, Mississippi. Purchased by Stephen D. Lee in 1879 and most likely the teenage home of Blewett Lee. Courtesy of the Local History Department at the Columbus Public Library, Columbus, Mississippi.

Sources and suggested readings:

Ballard, Michael B. Maroon and White: Mississippi State University, 1878-2003. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2008.

Hattaway, Herman. General Stephen D. Lee. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1976.

Lee, Blewett. “The Conjurer.” Virginia Law Review 7, no. 5 (February 1921): 370-377.

_________. “The Fortune Teller.” Virginia Law Review 9, no. 4 (February 1923): 249.

_________. “Psychic Phenomena and the Law.” Harvard Law Review 34, no. 6 (April 1921): 625-638.

_________. “Sovereignty of Air.” The American Journal of International Law, 7, no. 3 (July 1913): 470-496.

_________. “Spiritualism and Crime.” Columbia Law Review 22, no. 5 (May 1922): 439-449.

Lee, Percy Maxim and John Glessner Lee. Family Reunion: An Incomplete Account of the Maxim-Lee Family History. Privately printed, 1971. Special Collections, Mitchell Library, Mississippi State University.

Papers of Stephen D. Lee, University Archives, Mississippi State University.