The history of the Colonial Natchez District, Mississippi’s most successful early European settlement, is one frequently told through the eyes and accounts of White settlers. Yet, Natchez was built primarily through the backbreaking work of enslaved Africans. During Natchez’s first century, people from Europe and Africa, along with Native Americans, struggled with each other over land, labor, and wealth. However, not all Africans in Natchez were enslaved. Free people of color also lived as oddities in this world, which defined Black people as enslaved and White people as free. Nevertheless, free people of color were a part of Natchez’s history from the very beginning. Their story is closely linked to French dreams of imperial wealth, British nightmares of governing a too far-flung American empire, and Spanish illusions of creating a colony in the lower Mississippi Valley.

This article highlights the struggle of free people of color in Natchez to carve out a life of liberty in an utterly hostile environment. Not only did free Black people have to contend with slavery and a strict racial hierarchy in the colony, but they also had to fight for survival alongside African enslaved people and White Europeans. Nevertheless, the free people of color used their understanding of laws, families, and imperial rivalries to gain freedom, frequently against the will of their masters.

Status of free Black people in colonial Natchez

Free Black people occupied the lowest rung in Natchez’s free society, yet they often did invaluable work for the community. They served as warriors, farm hands, midwives, maids, traders, and as companions in a frontier town starved of White female settlers. Free Black people saw their fates twist in the wind as French, British, Spanish, and American customs and laws broadly influenced their legal standing in society. With the governance of Natchez changing hands at alarmingly frequent intervals, they had to brave these changes head on. As the imperial rulers of Natchez shifted, the liberty of free people of color remained on unstable footing. Free people of color, however, are an important part of Mississippi’s history, and by studying their lives, it allows us to open a window into a world often ignored by contemporary Mississippians. Following the stories of free people of color leads to evidence of the struggle that was the settlement of Natchez, the violence it entailed, and the instability of personal fortunes in the Old Southwest. By tracing the personal fates of free Black people in Natchez in relation to social upheaval and imperial change, we can gain a more complete understanding of the origin of Mississippi’s society. Unlike common perception—or misconception—Mississippi’s origins are not found in the mansions of antebellum plantations, but in the fight to survive colonial disorder. Free people of color were always a part of that story, and their frequent absence in Natchez’s printed history should be remedied.

The French, the Natchez Indians, and free people of Color

The first known free Black person in Natchez was connected to the Natchez Indians and their struggle against French intrusion. In 1723, violence erupted between the French and the Natchez Indians, who dominated the region. The French were keenly aware of the role that Black people played in the backcountry of their empire. On November 23, 1723, the minutes of the Superior Council of Louisiana reported a French ultimatum to end the current conflict with the Natchez. This demand read: “That they [the Natchez Indians] bring in dead or alive a negro who has taken refuge among them for a long time and [who] makes them [sic] seditious speeches against the French nation and who has followed them on occasions against our Indian allies.”

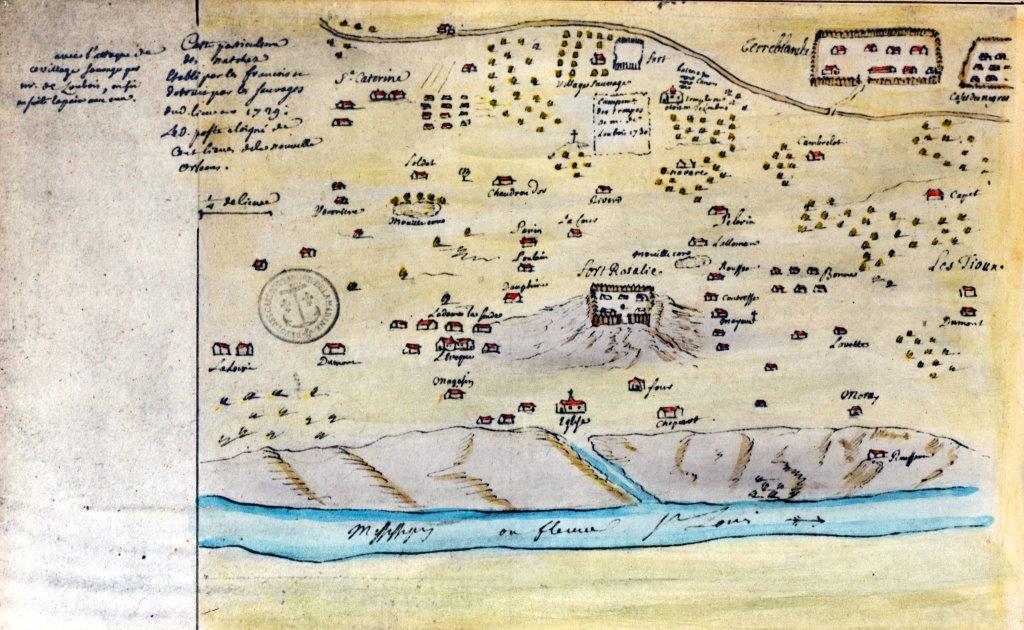

The French managed to arrest and to execute the unnamed African in 1723, but it has been impossible to trace the origins of this free man of color who endangered the French empire through his role as a Black leader among Native Americans. By threatening the French position in the Natchez District, he upset the imperial and racial balance in the area and invoked the fear of a cross-racial alliance among Africans and the Southeastern Indians. The free African’s presence countered the divide-and-conquer strategy the French often employed in Indian relations and forced them to widen that strategy to keep the enslaved and American Indians in the region divided as well. An alliance between Africans, enslaved or free, and Indians was rightfully perceived as a fatal combination for European settlers. In 1729, this combination spelled disaster for the French colony at Natchez in what is referred to today as the Natchez Rebellion.

Free women of color in Natchez

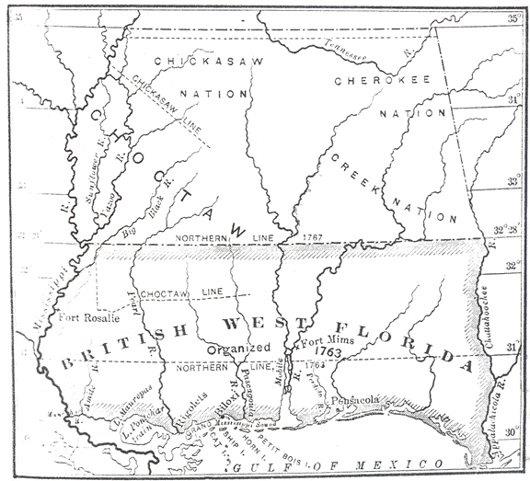

In the aftermath of the rebellion, France essentially vacated the district, and there are no records of free Africans in the area until Natchez became part of British West Florida under the Treaty of Paris in 1763. The British tried unsuccessfully to establish plantations and to bring a larger enslaved population to Natchez. Although records are few, there were at least two free people of color present in Natchez between 1763 and 1779. One, a woman named Nelly Price, is of particular note. She challenged social norms and openly defied a leading English merchant. Although Price’s stand ultimately led to a physical altercation, she managed to escape further punishment and reappeared frequently in Spanish records.

Nelly Price was the first in a long line of Black women in Natchez who fought for the right to be treated fairly in commerce and to be afforded human dignity. In a society that stacked the odds against them, these free black women sought ways to survive after bondage, often opting to attach their fate to that of other White settlers. Seeking protection and maybe companionship, these women faced tremendous challenges, but often remained triumphant. Price is a good example of that struggle. While she endured physical altercations with White male settlers in order to maintain her struggling enterprises under English government, her hard times changed in 1779 when Spain conquered Natchez. Almost immediately, Spanish laws allowed free people of color to use the courts to remedy their complaints. Price often made use of the courts and frequently received a favorable verdict. She was not the first Black woman, however, to obtain justice in Natchez.

Jeanette used the Spanish courts in 1782 to free her son, Narcisse, from slavery. Narcisse registered his freedom under the watchful eye of his father, Charles de Gran Pre, the military commandant of Natchez at the time. Jeanette set a precedent for women by proving that Spanish courts would hear free Black people’s pleas and act in accordance with the law, something that English law rarely provided. Narcisse and his mother joined a growing population of free people of color in the small town, which rocketed from two in 1779 to well over 150 in the first census taken by the Americans in 1801.

Free persons of color and the Spanish courts

Free Black people continued to use the Spanish courts in their favor. Black men used the courts to sue for debts owed to them or to reclaim property, and Spanish courts ruled according to the evidence. A Black man named James received payment owed to him for a load of grains that had been previously bought by two white inhabitants of Natchez. “Negress Betty” sued for an outstanding bill against James Willing, the infamous raider, and won her claim. As mentioned, Nelly Price was regularly in court, suing for services rendered and for outstanding debts, and she was frequently successful. Samba, a free man from New Orleans, was able to buy, and subsequently free, his daughter Nannette according to Spanish legal custom in Natchez. Although many of the free Black people in Spanish Natchez were able to take advantage of the new laws, many more did not.

United States governance of Natchez

Ultimately, Spain’s hold on Natchez proved tenuous. In 1795, the American republic successfully negotiated the deliverance of Natchez to the United States under the provisions of the Treaty of San Lorenzo (also called Pickney’s Treaty), and American law followed. The fortunes of Amy Lewis, a supposedly free Black woman, and her son fell victim to that change. After the death of Ashael Lewis, Amy’s master and her son’s father, Amy and her son were freed by the last will and testament of the deceased. But their freedom was quickly in peril, as White relatives of Ashael Lewis fought the will in court. Under Spanish rule, both mother and son remained free for the duration of the court case, and the odds were good to maintain their liberty. However, the case was filed in 1795 and dragged on through 1798, thereby crossing the intersection of the Natchez District’s territorial transition to the United States. Under the American territorial courts, Amy was re-enslaved, and her son, then a minor, was set free to fend for himself.

Free people of color played important roles on the frontier. The study of their stories provides a better understanding of the world on the banks of the Mississippi River in a much deeper way. Although their enslaved brothers and sisters often remain unknown, their stories hidden in the past, Natchez’s free Black population proved that liberty could be taken, not just bestowed, and they were public reminders of the inhuman system that was slavery. As they fought for their own rights and freedoms, they put the injustice of chattel slavery on public display.

Christian Pinnen is an assistant professor of history at Mississippi College

Other Mississippi History Now Articles

A Contested Presence: Free Black People in Antebellum Mississippi, 1820–1860

The Forks of the Road Slave Market at Natchez

Resistance by Enslaved People in Natchez, Mississippi

Mississippi Under British Rule – British West Florida

-

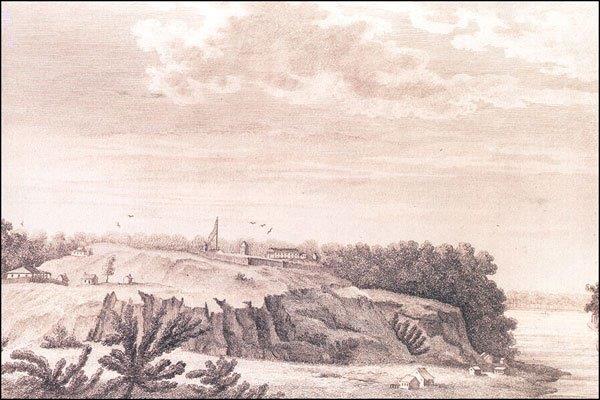

The French constructed Fort Rosalie on the Mississippi River in 1716 near the site of Natchez. Image courtesy of the Mississippi Department of Archives and History. -

Illustrated map of Fort Rosalie in French Natchez with seal, circa 1729. Image courtesy of the Natchez Historical Society, Scharff Collection, P-14.

-

British West Florida and Indian Nations. The British assumed control over the Natchez District in 1763 from France. Image courtesy of the Mississippi Department of Archives and History. -

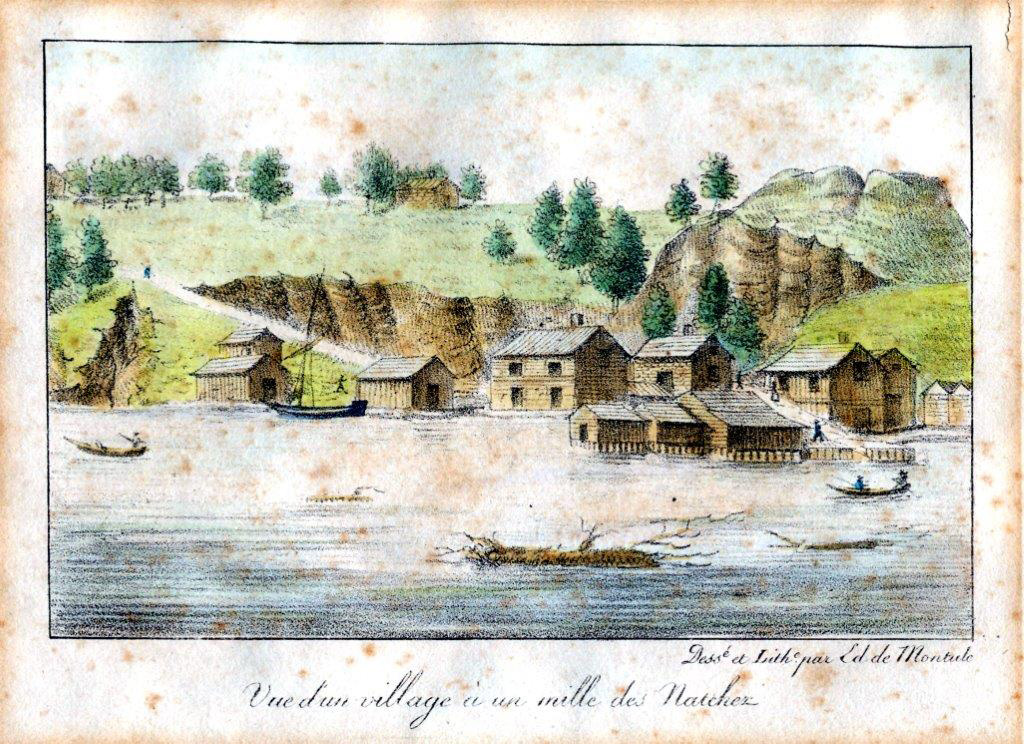

Village of Natchez in early 1800s by Edouard de Montule. Image courtesy of the Natchez Historical Society, Scharff Collection, P-5.

Sources and Suggested Readings

Archivo General de Indias, Seville, Spain

Papeles de Cuba

Dolph Bricoe Center for American History, University of Texas, Austin

Natchez Trace Collection, Provincial and Territorial Records

Mississippi Department of Archives and History

Mississippi Provincial Archives, British Dominion

Natchez Court Records, Adams County Courthouse, Natchez, Mississippi

Original Spanish Records, 1781-1798

Land Deed Records, 1798-1820

Hall, Gwendolyn Midlo. Africans in Colonial Louisians: The Development of Afro-Creole Culture in the Eighteenth Century. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1992.

Haynes, Robert V. The Natchez District and the American Revolution. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1976.

Haynes, Robert V. The Mississippi Territory and the Southwest Frontier, 1795-1817. Lexington: The University Press of Kentucky, 2010.

Holmes, Jack D. L. Gayoso: The Life of a Spanish Governor in the Mississippi Valley, 1789-1799. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1965.