In January 1903, President Theodore Roosevelt refused to accept the resignation of Minnie Geddings Cox, postmistress for the city of Indianola and Mississippi’s first African American postmistress. Roosevelt subsequently closed Indianola’s post office, and it remained closed for more than a year. The newspapers referred to the post office closing as the “Indianola Affair.” Cox’s role in the Indianola Affair, however, has been reduced to a footnote in early twentieth-century United States history. Except for a scant mention in history textbooks, Cox has almost disappeared from public memory, and her experiences have been rendered subtext for what the Indianola Affair was really about. For most scholars, the affair is merely a background sketch to the more important, central dramas of James K. Vardaman’s 1902 election as governor under Mississippi’s new direct primary system, the failure of two-party politics in the early twentieth-century South, and debates over Roosevelt’s progressiveness on the question of race.

The Indianola Affair and its central cast of characters tell a much more complicated story of historical transformations in the early twentieth century that had far-reaching consequences. The key to understanding the Indianola Affair necessitates careful “blocking,” a theatrical term that describes moving actors around in a scene. The actors’ placement and movements, rather than dialogue, convey their inner motivations and the deeper significance of their actions. It is critical to place Cox back at center stage, but doing so presents a considerable challenge. Only one letter and no diaries or interviews by Cox have been preserved in the archival record, and she left no personal record that scholars can use to hear her voice. Nevertheless, it is important that scholars attempt to reconstruct stories like Cox’s that have been drowned out by the cacophony of louder, better-documented historical voices. When Cox’s own experiences are returned to the forefront, the Indianola Affair not only remains an important facet of American political history, but it takes a more prominent place within the long history of the black liberation struggle in the United States. Moreover, it also blurs the stark divide between accommodation and protest as strategies in early twentieth-century African American political thought.

Delta Postmistress

Minnie M. Geddings was born in Lexington, Mississippi, in March of 1869 to former slaves, William and Elizabeth Geddings. Few details exist about her early life, but it appears that she lived a life of some privilege compared to most other African Americans living in the Mississippi Delta at the time. As business owners, Minnie’s parents were able to send her to Fisk University in Nashville, Tennessee, where she was part of one of the largest cohorts of women (over 100) attending Fisk during the period. While at Fisk, she recognized the leadership potential of educated African American women. Geddings graduated from Fisk’s normal school program around 1888, and she moved to Indianola to teach in the new segregated public school. Her future husband, Wayne Wellington Cox, helped establish the school in the early 1880s and served as its principal. The two married in October of 1889, and they later had one daughter, Ethyl.

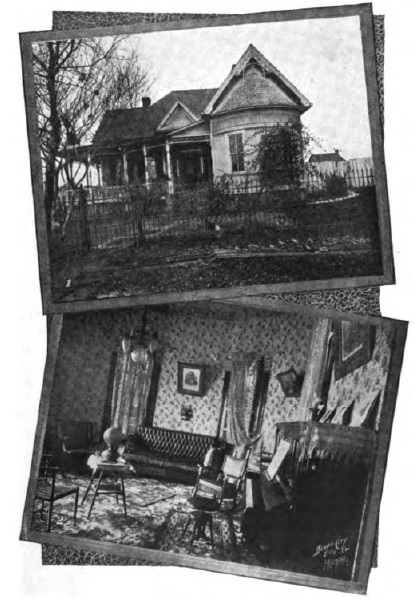

The Coxes lived on the predominantly white side of the railroad tracks in Indianola in a two-story frame house on Faisonia Street. In terms of education and income, the Coxes shared more in common with their white professional-class neighbors, who were doctors, merchants, and office workers, than they did with the majority of African Americans in the Mississippi Delta, who were mostly limited to servile positions such as domestics and low-skilled laborers. The Coxes maintained connections with the African American community, although from positions of greater privilege and influence. The Coxes spent several years in the town as educators. Nearly two dozen farmers rented land on a plantation in Sunflower County that Minnie owned, and thirty families rented properties that both Coxes owned in Indianola and other locations throughout the Mississippi Delta.

Wayne Cox, like many ambitious African American men throughout the country, remained active in the Republican Party. He controlled federal patronage positions at the local level for African American and white Republicans, as well as some white Democrats. Setting aside Wayne’s political influence, however, Cox probably pursued the postmistress position on her own. She sought her husband’s assistance rather than his permission in order to accomplish her own goals. Raised by business owners and educated at one of the premier schools for aspiring African American women, Cox sought opportunities beyond the traditional expectations for women of the time. In 1891, President Benjamin Harrison appointed Cox to the position of postmistress for Holmes County, making her the first African American postmistress in Mississippi. However, she was not, as many sources assert, the first African American postmistress in the United States. At least twelve African American women served as postmistresses in the nineteenth century. Minnie lost her appointment when a Democratic president (Grover Cleveland) took office in 1894. However, when Republican William McKinley won the presidential election in 1897, he appointed Cox as postmistress of Sunflower County.

Cox operated the Sunflower County post office that served over 3,000 patrons a year and operated out of the Cohen’s Brooklyn Bridge Store in Indianola’s central business district. She installed a telephone for customers’ use, at her own expense, and also opened the post office for a few hours on Sundays after church services for her customers’ convenience. Cox even used her own money to pay delinquent postal box rents for both white and African American customers. Cox performed well in the position, earning an “Excellent” rating from federal postal inspectors. In 1900, due to the volume of mail passing through the Indianola post office, President McKinley promoted Cox to third-class postmaster. The promotion came with a new four-year appointment and an increase in salary to $1,100 a year (about $32,200 in today’s dollars)—a very significant sum at that time. As a teacher, she would have earned only a third of that amount. The Coxes’ college educations, land and property holdings, civil servant positions, and comfortable salaries placed them firmly near the top of the social and economic hierarchy in the region—and in the crosshairs of mounting racial and political tensions.

White agitation

Around 1902, whites in the Mississippi Delta channeled their anxieties onto African Americans. Their anxieties grew from the combination of an economic depression, a power grab by the southern wing of the Republican Party, and an aggressive political contest for governor. Cox found herself in the crosshairs of these conflicts. As the Mississippi Delta slid into an economic depression at the turn of the twentieth century, Cox’s relationship with the white residents of Sunflower County worsened in proportion to the county’s economic fortunes. Plummeting cotton prices pushed white farm owners and laborers down the slippery slope of tenancy and debt peonage. After two seasons of failed crops, white farmers, business owners, and workers suffered financially. They resented the success of African Americans like the Coxes and scapegoated African Americans for the reversal in whites’ economic fortunes.

Political intrigue also compounded Cox’s troubles. President Roosevelt made modest moves to strengthen and reform the Republican Party in the South, which many white Southerners saw, in the words of the Greenwood Commonwealth’s then-editor James K. Vardaman, as federal efforts to promote “negro domination.” Closer to home, the Mississippi governor’s race of 1903 also increased the pressures on Cox. Vardaman, who was a Democratic candidate for the office, committed himself to a political platform that ensured the gulf between the races would remain interminable and impassable.

James Kimble Vardaman

Vardaman was no stranger to Mississippi politics. He had served two terms in the state legislature but failed to win the Democratic Party’s nomination for governor on two prior occasions. The state’s 1902 Primary Law provided Vardaman with an opportunity to gain the political office that had previously eluded him. In his direct appeals to voters, Vardaman milked racial divisions and animosities to his political advantage. His platform called for such draconian policies as ending all tax support for African American schools in the state and repealing both the 14th and 15th Amendments of the U. S. Constitution. Ironically, other aspects of Vardaman’s politics fell within the policies of political progressivism. The open primary system represented, according to reformers, a positive move away from nominations by state convention, a system that was rife with corruption. The open primary created by the 1902 Primary Law increased the democratic potential of all white men in the state, regardless of class or property-holding status. The 1890 Mississippi Constitution, the first in the United States to disenfranchise African American men, made sure African Americans were not imagined as part of either democratic or progressive reforms.

Haunted by two previous failures, Vardaman shook thousands of hands, visited dozens of Mississippi towns, and penned scores of editorials warning that “negro domination” posed a threat to white civilization and democracy. He singled out Cox as a particular threat. When Vardaman stumped in Indianola, he berated white Indianolans for allowing a “negro wench” to handle their mail. In his campaign for the hearts and minds of locals, he appealed to white Mississippians’ democratic ideals, as well as their racial fears and prejudices.

Vardaman’s venom reinforced rather than formed the political anxieties, economic fears, and racial discontent within Mississippi. Outnumbered by African Americans two to one, white Indianolans felt it important to send a message to the city’s African American citizens that they should remain “in their place.” Whites from all classes and backgrounds signed petitions urging Roosevelt to remove Cox from her position as postmistress and replace her with a white man. At a public meeting in October of 1902, civic and business leaders denounced Cox, lacing their threats with racial epithets. Some whites claimed African Americans loitered, played cards, and gambled at the post office. The town’s white civic and business elite deployed language rooted in racial and sexual stereotypes that disempowered African American women and justified sexual and mob violence against them. The charged rhetoric was one way whereby whites projected sexual and racial degeneracy onto public spaces. The post office, like stores, trains, and courthouses, became a site of struggle over white power and black subservience.

Wayne Cox appealed to his white political friends and the U. S. Postmaster General for help in defusing the situation in Indianola, but these individuals could do very little against the open and covert threats of violence by local whites against Cox. Fearing that a white mob would destroy the post office, Minnie Cox wrote a U. S. Postal Inspector in early December of 1902 “if I don’t resign there will be trouble.” Her fears were not without merit. In 1898, mobs had burned the post offices and homes of two African American postmasters in South Carolina and Georgia. The mobs then murdered both postmasters, as well as the infant daughter of one of the postmasters.

The Indianola Affair

On December 4, 1902, Cox tendered her resignation that would take effect on January 1, 1903. President Roosevelt refused to accept it, later stating, “I cannot consent to take the position that the door of hope—the door of opportunity—is to be shut upon any man, no-matter [sic] how worthy, purely on the grounds of race and color.” Roosevelt’s tender sentiments, however, held no power to stop a lynch mob and did little to limit white Democrats’ control in the state and region. Cox’s resignation was public knowledge, but her situation grew more perilous. Whites in Arkansas and other nearby Southern states threatened to come to Indianola and kill her. A fearful Cox refused to return to the post office, and it remained closed for much of December. The most serious threat to Cox occurred on January, 4, 1903, when she heard noises outside her home. That same evening, a federal postal inspector’s unexpected visit thwarted a would-be lynch mob plotting at the sheriff’s home. The next morning, Cox and her entire family left town.

The Indianola Affair galvanized opinions on both sides. Throughout 1903, newspapers and magazines across the country reported on the post office closure. Some of the headlines in white papers were insulting and used racial epitaphs. The response of the African American press was varied. Some used the affair as a symbol of outrage that, alongside disenfranchisement statutes, signified efforts to block the political ambitions of African Americans throughout the country. Some praised Roosevelt’s actions and identified the roots of the post office closure in political jealousies and factionalism. Others, however, openly criticized how Roosevelt handled the incident. Some papers even expressed militant sentiments, calling for African Americans to take up arms. African Americans around the country saw Cox’s experience as an allegory of their own disenfranchisement and struggle for equality. As much as Cox’s race, education, and economic standing invited the ire of anxious whites experiencing a reversal in their own fortunes, these same characteristics made Cox particularly potent as a symbol of African American achievement.

Cox spent most of her exile from Indianola in Birmingham, Alabama. There, the Coxes lived with a close family friend: John “Bob” Tarry, one of the richest African Americans in Birmingham. As Tarry’s live-in guests, the Coxes most likely circulated among the city’s African American business and social elite. Though the Coxes rejected Booker T. Washington and Isaiah Montgomery’s call to sideline political ambitions (Wayne remained active in the Republican Party), they embraced Washington’s call to develop business opportunities as a response to political disenfranchisement and social segregation. The Coxes returned to Indianola in February of 1904. Several months later, they opened the Delta Penny Savings Bank. Cox served as the bank’s vice president; after her husband’s death in 1916, she became secretary-treasurer, a position even more powerful than the bank’s president. The second African American-owned bank opened in Mississippi, Delta Penny became the largest and most successful African American-owned bank in the state until it closed in 1928. In 1908, the Coxes opened an insurance company, Mississippi Life Insurance Company, which became the first African American-owned insurance company in the United States to offer whole life insurance. Both the bank and the insurance company helped finance homes and other African American businesses throughout the state. It also helped thousands of families build modest wealth. Along with other enterprising Afro-Mississippians, the mission of business creation, economic development, and employment indicated that African Americans refused to operate at the margins of the Jim Crow economy and society in Mississippi. The Coxes’ strategy challenged the false boundaries between accommodation (accepting some discrimination to achieve economic success) and agitation (protesting for social and political equality).

The Indianola Affair in historical perspective

The Indianola Affair reminded well-to-do African Americans that material success did not guarantee physical security. It actually increased the likelihood that they would become targets of lynching and other forms of extralegal violence as well as continued harassment and exclusion. Cox’s fellow Mississippi native Ida B. Wells and the activist-scholar W. E. B. Du Bois were among some of the earliest voices to raise awareness about the links between African American economic achievement and extralegal violence.

Thus, the struggle over the tiny post office in Indianola foreshadowed struggles for social justice, economic opportunity, and political power that resonate with present-day challenges that still call out for change. At the time, the Indianola Affair sparked the first major debate about race, states’ rights, and federal power in the United States Congress since Reconstruction. It also highlighted the complexities of African American political responses. The Coxes valued the formal ballot, but they embraced business and economic development as equally important responses to address institutional and structural inequities. In the present day, Americans continue to wrestle with racism and the erosion of democratic rights at every level of government, from the local to the federal. They also wrestle with economic justice, revealing radical activist sentiments in calls to address economic inequities, seen most vividly in boycotts, “buy black” campaigns, and collective efforts during the Civil Rights Movement and, most recently, in the #BankBlack movement.

Shennette Garrett-Scott is assistant professor of history and African American studies at the University of Mississippi.

Lesson Plan

-

Photograph of Minnie and Wayne Cox’s home and parlor, circa 1911. The furnishings and piano in the Coxes’ private home conveyed the refinement and culture they sought to display to the outside world. Source: Beacon Lights of the Race, edited by G. P. Hamilton (E. H. Clark and Brother, 1911), 223. -

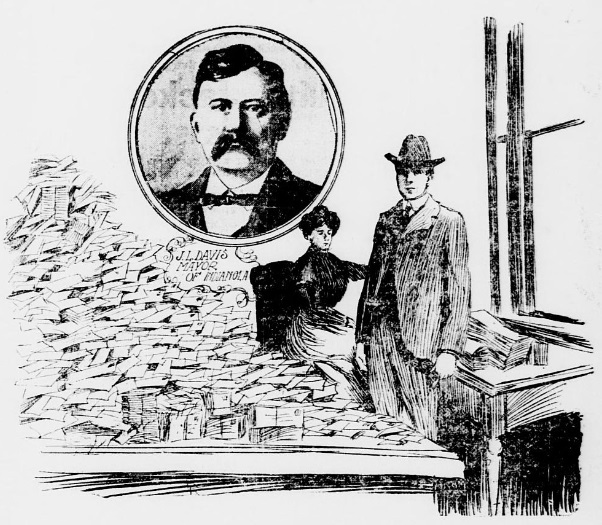

A newspaper image purporting to show the undelivered mail in Indianola’s post office. President Theodore Roosevelt refused to appoint a new postmaster and reopen the post office. He actually diverted the mail to nearby Greenville and then Heathman. Source: “President’s Plan to Reopen Post Office and Reinstate Negro Postmistress,” St. Louis Republic, January 11, 1903, Part I, p. 1.

-

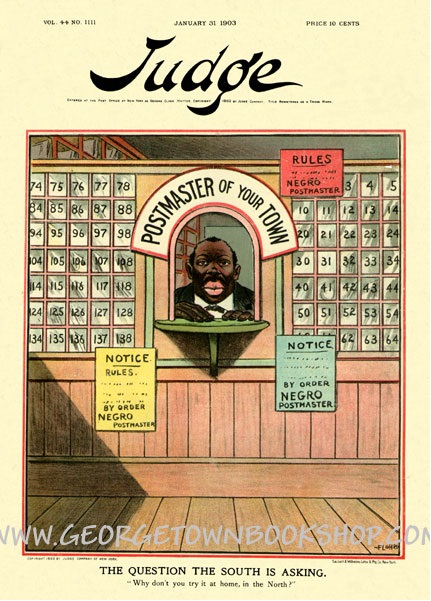

This magazine cover from Judge magazine (January 31, 1903) features an image of a male postmaster, but the cartoon alludes to Cox and the Indianola Affair. It reflects the racial, sexual, and economic anxiety surrounding issues of racial equality, federal power, and states’ rights in the Deep South that the Indianola Affair injected into the national discourse for the first time since Reconstruction. Source: https://www.georgetownbookshop.com/display2.asp?id=940. -

![This newspaper image of Minnie Cox appeared in African American newspapers, including the Colored American. The image communicates the wealth and affluence that made Cox a target of violence and repression for local whites but also a symbol of achievement and progress for African Americans around the nation. Source: [“Mrs. Minnie M. Cox,”] Butte (Mont.) New Age, January 31, 1903, p. 4. The image communicates the wealth and affluence that made Cox a target of violence and repression for local whites but also a symbol of achievement and progress for African Americans around the nation.](/sites/default/files/imported-images/1105.jpg)

This newspaper image of Minnie Cox appeared in African American newspapers, including the Colored American. The image communicates the wealth and affluence that made Cox a target of violence and repression for local whites but also a symbol of achievement and progress for African Americans around the nation. Source: [“Mrs. Minnie M. Cox,”] Butte (Mont.) New Age, January 31, 1903, p. 4.

Sources and suggested readings:

Garrett-Scott, Shennette. “Cox, Minnie Geddings,” In The Mississippi Encyclopedia, edited by Ted Ownby, Charles Reagan Wilson, Ann J. Abadie, Odie Lindsey, and James G. Thomas. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi; Oxford: Center for the Study of Southern Culture, University of Mississippi, 2017.

Garrett-Scott, Shennette. “To Do a Work that Would Be Very Far Reaching: Minnie Geddings Cox, the Mississippi Life Insurance Company, and the Challenges of Black Women’s Business Leadership in the Early Twentieth-Century United States.” Enterprise & Society 17, No. 3 (September 2016): 473–514.

Historian of the U. S. Postal Service, “African-American Postal Workers in the 19th Century,” http://about.usps.com/who-we-are/postal-history/african-american-workers-19thc.pdf.

Primary Sources

[“Mrs. Minnie M. Cox,”] Butte (Mont.) New Age, January 31, 1903. (See full page image at http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov.)

“President’s Plan to Reopen Post Office and Reinstate Negro Postmistress,” St. Louis Republic, January 11, 1903. (See full page image at http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov.)

U. S. Congress. Congressional Record. “Post-Office at Indianola, Miss., January 15, 1903,” Congressional Record Index, Vol. 36, No. 11 (January 5, 1903, to January 17, 1903), 57th Cong., 2nd Sess. (Washington, D.C.: General Printing Office, 1903): 842–44.

U. S. House of Representatives. House Reports, No. 422, Resignation of the Postmaster at Indianola, Miss., Serials 4531, 57th Cong., 2nd Sess. (Washington, D.C.: General Printing Office, 1903–1906).

On the role of the Indianola Affair in regional and federal U.S. political history:

De Santis, Vincent P. “The Republican Party and the Southern Negro, 1877–1897.” Journal of Negro History 45, No. 2 (April 1960): 88–102.

Gatewood, Willard B. “Theodore Roosevelt and the Indianola Affair.” Journal of Negro History 53, No. 1 (January 1968): 48–69.

Mowry, George E. “The South and the Progressive Lily White Party of 1912.” Journal of Southern History 6, No. 2 (May 1940): 237–47.

Scheiner, Seth M. “President Theodore Roosevelt and the Negro, 1901–1908.” Journal of Negro History 47, No. 3 (July 1962): 169–82.

On the racial, political, and economic climate of the Mississippi Delta in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries:

Cobb, James C. The Most Southern Place on Earth: The Mississippi Delta and the Roots of Regional Identity. New York: Oxford University Press, 1992.

McMillen, Neil R. Dark Journey: Black Mississippians in the Age of Jim Crow. Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 1990.

Woodruff, Nan Elizabeth. American Congo: The African American Freedom Struggle in the Delta. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2003.

About the Mississippi Constitution of 1890

John Marshall Stone: Thirty-first and Thirty-third Governor of Mississippi: 1876-1882; 1890-1896

James Kimble Vardaman: Thirty-sixth Governor of Mississippi: 1904-1908

Was Mississippi a Part of Progressivism?

Ida B. Wells: A Courageous Voice for Civil Rights